Early this year I spent time in China, specifically in Zigong, Sichuan Province. I was there for day-job reasons (acting as consultant for life-sized dinosaur models), but when not working I went and looked at giant pandas, and at the many amazing skeletons of Jurassic dinosaurs (and other fossil vertebrates) at Zigong Dinosaur Museum. I also did a fair bit of birdwatching, both in the various gardens and green spaces I could get to it but also in the urban and suburban places within easy distance of my accommodation. And I saw a bunch of stuff, which is what I want to talk about here.

Caption: come on - everybody loves White-browed laughingthrushes Pterorhinus sannio! More on this species below. Image: Darren Naish.

First things first. To identify the birds of a given region, you need a goddam field guide. Thinking it would be easy and simple to get a ‘Field Guide to the Birds of China’ before setting off, I went to buy one (I recall looking in Foyles in London’s Charig Cross Road, since it has an excellent field guide section) buuut…. nope. Nothing. After looking around online a bit I discovered John MacKinnon* and Karen Phillipps’s 2000 A Field Guide to the Birds of China. Which is great apart from the fact that it costs over £40, and usually over £50, which is above what I consider affordable for books. Goddammit. On this occasion, however, my luck was in since a special sale at NHBS meant that I was able to get it at half price (albeit not until long after my trip had happened).

* Yes, of Saola fame and so, so much else.

Caption: MacKinnon & Phillipps (2000), A Field Guide to the Birds of China. It’s not the most attractive field guide out there, but it does seem to be the best one. Image: Darren Naish.

Regular TetZoo readers might have heard me complain about book prices before. Books are horrendously over-priced, a thing I can’t help but feel angry about given that – as someone who’s spent most of their life in relative poverty – it bothers me a lot that knowledge is so frequently locked away unless you’re lucky enough to be able to afford access to it. Anyway, I digress.

Caption: feral pigeons and Whooper swans in China. Discussed below. Images: Darren Naish.

I should say that this was my first ever trip to China, and that I’d been told (no offence intended to Chinese friends and colleagues) to expect to see nothing in the way of wild animal life in view of relevant environmental issues. While I certainly saw places where pollution was bad and natural spaces were being destroyed or degraded, the good news is that I still saw a fair amount of wildlife – though, birds only. I should also add that the avifauna was – to my western European eyes – an interesting mix of the familiar and commonplace with the obscure and exotic. Aaaaand I should also add that my photos are mostly terrible. The skies were leaden grey and the lighting terrible during my entire time in China, plus birds are fast and my camera is not that great. So, apologies.

Caption: rallids and grebes of China. At top left: Common coot Fulica atra. At top right: Common moorhen Gallinula chloropus. Below: Little grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis. Image: Darren Naish.

Anyway, to business. What did I see? We’ll start with the larger birds. While at the ornamental lake at Chengdu Panda Base (or, more formally: Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding), I saw Whooper swan Cygnus cygnus, Ruddy shelduck Tadorna ferruginea, Common coot Fulica atra, Common moorhen Gallinula chloropus and Little grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis. Coots, moorhens and Little grebes are birds I see regularly here in the UK, but more interesting were the several small raptors circling nearby. I’m not totally sure what they were and my photos are poor, but the small-headed look, extensive barring, dark primaries and lack of transverse bars on the tail make me think that this is either a Buteo or Butastur hawk or a baza. There are several accipiters in Sichuan but I don’t think that’s what we’re seeing here. Thoughts?

Caption: small, broad-winged raptor… of some sort. Image: Darren Naish.

Feral pigeons Columba livia were a thing, which isn’t a surprise but is still something you might need confirming. Then there’s this pigeon…

Caption: what is this pigeon… or dove, if you want? Read on. Both photos show the same individual, photographed at Chengdu Panda Base. Image: Darren Naish.

It’s a mid-sized, long-tailed, mostly brown, grey-headed, red-legged pigeon that I saw walking on the ground a fair bit. Spots and barring look absent. But... I’m pretty sure that this a Spotted dove Streptopelia chinensis, though I had trouble realising this since the diagnostic spotted patch on the neck isn’t visible in my photos. Or am I wrong?

Shrikes. Now we come to passerines, of which I saw a bunch. I’ll go through them in a very rough sort of phylogenetic order, rather than in the order in which I encountered them. I saw shrikes in several places, often in towns and right next to tower blocks and in very urban settings (so long as there are trees and green spaces, there can be birds). All appeared to belong to the same species, one with a warm brown mantle, grey crown and nape, black wing feathers but for a small, white, rectangular panel on the primaries, and long tail that was dark on its upper surface. Of the 12 shrike species in the region, this description applies only to the Burmese shrike Lanius colluroides, the black (rather than streaked white) forehead further showing that I only ever saw males… which figures, because they were usually singing.

Caption: Burmese shrike Lanius colluroides, two different individuals (the one at left is singing). This species occurs throughout south-east Asia as well as China and is mostly associated with lowland forests. Image: Darren Naish.

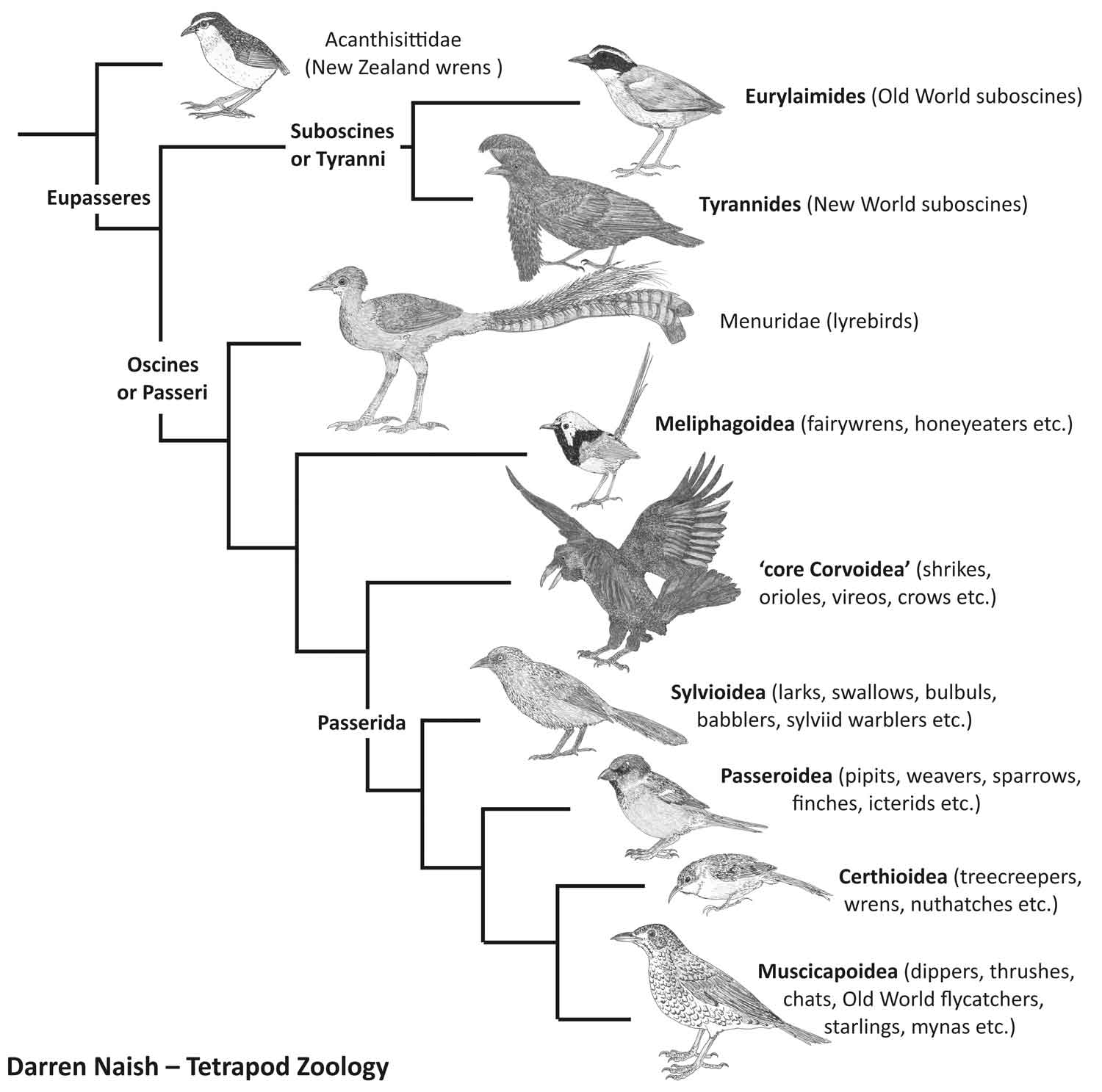

My impression in the field was that I was looking at Red-backed shrike L. collurio – a species I know well from fieldwork in Romania – but the Red-backed (which does occur in China) is quite different, mostly in being shorter-tailed. Furthermore, the Red-backed shrikes in China are restricted to the far north of the country and belong to the pale subspecies L. c. pallidifrons, the mantle of which is washed out relative to the reddy-brown present on Burmese shrikes and Red-backed shrikes in Europe. Shrikes are corvoids, by the way, and thus outside the clade – Passerida – that contains all the other passerines I’ll be talking about.

Sylvioids 1: bulbuls and laughingthrushes. Bulbuls, babblers, laughingthrushes and allied pointy-billed sylvioid passerines are not that typical of western Europe, so it was fairly thrilling for me that my first passerine of the entire trip was the Light-vented bulbul Pycnonotus sinensis, which I saw a lot and often right in the middle of urban areas (again, so long as there were trees).

Caption: Light-vented bulbul Pycnonotus sinensis. Different individuals seen, variously, in an ornamental garden and in a planted region in the middle of a heavily pedestrianised area. Images: Darren Naish.

I also saw White-browed laughingthrushes Pterorhinus sannio at many places, including parks and gardens. I was often able to get really close to them. They forage on the ground a lot, often in pairs or small groups, and also hang around in low vegetation. I was also happy to see Red-billed leiothrix Leiothrix lutea in the wild, a small laughingthrush well known outside of Asia as a cage bird. Leiothrixes are among those many passerines where the vernacular name is the same as the scientific one. Other examples include tesias, liocichlas, eremomelas, prinias, cisticolas, hyliotas, batises, tschagras and so on and on.

Caption: at left, White-browed laughingthrush Pterorhinus sannio singing. At right: Red-billed leiothrix Leiothrix lutea. Images: Darren Naish.

Sylvioids 2: leaf warblers and bush warblers. Below, we see a leaf warbler (or phylloscopid). There are about a million leaf warbler species in China and they’re notoriously difficult to identify with confidence, certainly so when you’re looking at poor photos and not with the birds in front of you. I initially reckoned that this might be a Yellow-browed warbler Phylloscopus inornatus on account of the two whitish wing bars. However, the bird I saw has a distinct central crown stripe, which is supposed to count that species out. A better match might be Pallas’s leaf warbler P. proregulus (a phylloscopid I always remember from field guides because it’s sometimes positioned close to kinglets, and both this and its specific name imply that it’s a ‘proto-kinglet’, which it totally isn’t). This is in keeping with the small bill and whiteish underside, plus P. proregulus is common across much of China and nearby (MacKinnon & Phillipps 2000).

Caption: definitely a phylloscopid… and perhaps a Pallas’s leaf warbler Phylloscopus proregulus. Both images show the same individual. Images: Darren Naish.

Phylloscopus leaf warblers are familiar birds to me (there are a few TetZoo ver 2 and 3 articles about them, or there used to be…), but I’d never before seen any member of the cettiid warbler genus Abroscopus. This (below) is the Rufous-faced warbler A. albogularis, a fairly common bush warbler of woods and thickets with a set of distinctive facial markings. My impression on seeing this bird in the field was that it was a fulvetta but I became confused when the markings totally didn’t match any known fulvetta species. Please excuse the terrible photo.

Caption: blurry Rufous-faced warbler A. albogularis, photographed in the gardens of the Zigong Dinosaur Museum. Image: Darren Naish.

Bushtits and actual tits. The same applies to my photos of Black-throated tit Aegithalos concinnus, an aegithalid (bushtit or long-tailed tit) I saw several times while individuals, often in mixed flocks with warblers, foraged in vertical and hanging poses. A few very similar aegithalids also occur in China – like the Rufous-fronted tit A. iouschistos and Black-browed tit A. bonvaloti – but the Black-throated has unmistakeable markings. Aegithalids are not really tits at all, by the way, but are instead close kin of phylloscopid and sylviid warblers (Jønsson & Fjeldså 2006, Selvatti et al. 2015) and thus deep within Sylvioidea. True tits (Paridae) appear to be an early-diverging lineage within Sylvioidea.

Caption: Black-throated tit Aegithalos concinnus, showing the head, throat, chest and belly markings diagnostic for this species. Images: Darren Naish.

Caption: this photo wasn’t taken in China, but in England, and shows an aegithalid species very familiar to European people like myself: the Long-tailed tit A. caudatus, which also occurs in China. Its long tail is not typical of all members of this group. Image: Darren Naish.

Of proper tits, I had good views of what I assumed were Great tit Parus major, a species which does occur across much of southern China. However, the Great tits in China have a white border to the black belly stripe and a single white wing bar, whereas the tit I saw (and photographed, really badly) had a yellow border to its belly stripe and two white wing bars. This means it must have been the Green-backed tit P. monticolus, and perhaps the subspecies P. m. yunnanensis (the more eastern form P. m. legendrei has a much wider black belly stripe, and the other subspecies occur further west or in Taiwan). Harrap & Quinn (1996) made the point that the relationship between Green-backed and Great tits is not well understood, since both have overlapping ecological preferences in some parts of their ranges and can even occur in the same feeding flocks. The Green-backed tit also occurs in places where there are distinct lowland and highland Great tit subspecies on either side, which is confusing. In general, the Green-backed tit seem to be a highland relative of the Great tit, more closely associated with wetter forests.

Caption: really bad photos of a tit which turned out to be a Green-backed tit Parus monticolus. Lighting conditions were often against me when I was getting these photos. Image: Darren Naish.

Pipits and wagtails, and sparrows. This (below) is an Olive-backed pipit Anthus hodgsoni, one of several of these birds that I watched foraging in rough ground in a heavily built-up area. Pipits are a really interesting group of passerines that have many adaptations for life in open areas like grasslands, meadows and tundra but there are also species of woodlands, rocky coasts and watercourses. They’re often leggy (for passerines) and with notably long hallux claws.

Caption: Olive-backed pipit Anthus hodgsoni, in characteristic theropod skulking pose. The Olive-backed pipit is a widespread Asian species, occurring from the edge of the Urals to the coasts of the Pacific and Indian oceans. Image: Darren Naish.

Pipits are closely allied to wagtails (both belong together within Motacillidae), and I saw one representative of that group too: the White wagtail Motacilla alba, a species well known for occurring in pedestrianised areas and other places with big, flat expanses of nothing. The White wagtail is well known for being highly variable across its vast range and numerous subspecies have been named (cue debate about which of these warrant specific status…). The one I saw is M. a. alboides, sometimes called Hodgson’s wagtail and associated with Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar and the Himalayas as well as the southern half of China (Alström & Mild 2003). Motacillids, incidentally, are part of the passerine clade Passeroidea, which is weird because it means that they’re surrounded in the phylogeny by sparrow-like birds (e.g., Selvatti et al. 2015).

Having mentioned sparrows, I saw Eurasian tree sparrow Passer montanus on several occasions, which is not surprising since this is the sparrow of China. House P. domesticus and Spanish P. hispanicus sparrows occur in China too, but only at comparatively few spots in the far west. China is also home to the Rock sparrow Petronia petronia and several snowfinches (Montifringilla).

Caption: at left, two different Hodgson’s wagtail Motacilla alba alboides, a subspecies of White wagtail. At right: Eurasian tree sparrow Passer montanus. Images: Darren Naish.

Thrushes and Old World flycatchers. Let’s talk briefly about thrushes. The blackbirds in China – here I’m talking about the black thrushes typically called ‘blackbirds’, not the American ‘blackbirds’ included in the group Icteridae – have conventionally been regarded as subspecies of T. merula, the thrush that occurs across Europe, Asia and northern Africa where it’s mostly known as the Common or Eurasian blackbird. However, some authors now regard at least some Chinese blackbirds as belonging to a distinct species: the Chinese blackbird T. mandarinus. Sichuan is apparently home to the subspecies T. m. sowerbyi, so this might be the bird I saw. In the field, the males struck me as being slightly greyer on the wings and browner on the body than the blackbirds at home in England, but the differences were minor.

Caption: a blackbird, foraging at the edge of a pond where stones have been stuck into cement. I would have thought that this is a Common or Eurasian blackbird Turdus merula, but it might be a Chinese blackbird T. mandarinus. Image: Darren Naish.

Thrushes are closely allied to Old World flycatchers, properly called Muscicapidae. China is home to loads of them, among them wheatears, stonechats, forktails and other chats, various redstarts, robins, nightingales, shortwings, bush robins and rock thrushes, many Ficedula and Muscicapa flycatchers, various niltavines, and others. I wasn’t in the right sort of places to see any of these, but I did see an iconic Asian member of the group: the Oriental magpie-robin Copsychus saularis, a familiar species of gardens and forests. Magpie-robins – also called shamas – are unusual enough that (together with the Cercotrichas scrub robins) they belong to their own muscicapid lineage, Copsychini (Sangster et al. 2010). Magpie-robins are sexually dimorphic. Males are strikingly black and white while females are mostly grey on the head and body, and I saw both.

Caption: Oriental magpie-robin Copsychus saularis male and female (male at top, female below). The male in the images here lived right next to a factory. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: another member of the muscicapid clade Copsychini, a male White-rumped shama Copsychus malabaricus. This one was photographed in captivity in the UK, not in Asia. Image: Darren Naish.

Starlings. China is inhabited by about 20 starling species, meaning that someone only familiar with the dark, iridescent Common starling Sturnus vulgaris – like me – is potentially in for a real treat. Alas, my only sightings were of the gregarious Red-billed starling S. sericeus. Like many of the Asian Sturnus species, its plumage combines black wing feathers with white patches, a varicoloured look to the body and a distinctly demarcated head. The birds I photographed look darker than those in many images of this species online but that’s mostly because I had to up the contrast to make them usable.

Caption: Red-billed starling Sturnus sericeus in downtown Zigong. There were about 15 birds in this group; the bird shown at left is the same individual seen at far right in the photo on the right. Image: Darren Naish.

And that’s it! I emphasise that the birds I’ve discussed here weren’t the sort that people travel half-way round the world to see, or go to remote places to tick off their lists. On the contrary, these were all birds that were easy to see in urban and suburban settings and my seeing of them was mostly opportunistic and done with minimal effort. My point in discussing the birds I saw was to explain what a normal person, interested enough in wildlife to go and look for it but not to spend huge sums of money on dedicated adventures, might bump into. The answer is… quite a lot, even in these times of environmental degradation and destruction. Some of my identifications could well be off, in which case please feel happy to correct me. More birds here sometime real soon, thanks for reading.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to the birds discussed here, see…

For The Love of Crows, October 2015

Thoughts on the Passerine Tree, 2016, October 2016

A Battle Among Blue Tits, February 2018

Refs - -

Harrap, S. & Quinn, D. 1996. Tits, Nuthatches and Treecreepers. A & C Black, London.

Jønsson, K. A. & Fjeldså, J. 2006. A phylogenetic supertree of oscine passerine birds (Aves: Passeri). Zoologica Scripta 35, 149-186.

Sangster, G., Alström, P., Forsmark, E. & Olsson, U. 2010. Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis of Old World chats and flycatchers reveals extensive paraphyly at family, subfamily and genus level (Aves: Muscicapidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57, 380-392.

Selvatti, A. P., Gonzaga, L. P. & Russo, C. A. de M. 2015. A Paleogene origin for crown passerines and the diversification of the Oscines in the New World. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 88, 1-15.