You’ve surely heard the recent news that a group of amateur researchers in Tasmania – led by a Mr Neil Waters – claimed (on March 1st 2021) to have photographed a group of living Thylacines Thylacinus cynocephalus….

Caption: one of the Thylacine Awareness Group photos released by Neil Waters and his colleagues. Alas, there’s no good reason to think that this shows a thylacine, or has anything to do with thylacines. Image: (c) Thylacine Awareness Group.

These images were then checked by experts, and determined to actually depict wallabies (specifically, pademelons). It was always obvious that we should have been extremely sceptical about the group’s claims, and indeed most relevant parties (myself included) expressed this right from the start. As you’ll know if you’re at all familiar with writings on mystery animals, innumerable claims about persisting thylacine populations have been made over the years and there’s a massive literature on this subject, both in popular cryptozoological books and articles (Dash 1992, Greenwell 1994, Healy & Cropper 1994, Bailey 2001), and in the semi-technical and technical literature on cryptozoology (Anon 1985, Douglas 1986, 1990) and marsupials (Rounsevell & Smith 1982, Smith 1982).

Caption: two of the key books to consult if you’re interested in thylacine extinction, and claimed post-extinction observations.

Such is the interest in this story that several high-profile articles have appeared, and among them is Asher Elbein’s piece in the New York Times, which has just been published today. I was one of the several experts Asher interviewed for that piece; naturally, the published version includes just a few choice quotes from our discussion. In the interests of recycling material where possible and riding bandwagons as and when they become, err, rideable, I thought it might be worth publishing the whole of the interview text here. With Asher’s permission, here it is. Asher’s sections are in quotes, my responses are below. My thanks to Asher for performing the interview in the first place, and for permission to reproduce the whole thing here at Tetrapod Zoology.

How long have people been reporting/looking for remnant thylacines? Was there ever a point where there was some broadly accepted possibility for their survival? Why do people think or hope they might still be around?

The search for 'living thylacines' is a confusing tale since there isn't any obvious point at which these searches switch from being reasonable efforts to check for what might still have been a rare, persisting animal to those that were or are desperately hopeful and unlikely to succeed. Falling in the first camp are expeditions of 1937 and '38: a time when the notion of thylacine persistence could still be considered a reasonable possibility. You could say the same for the expeditions of the 1940s. I get the impression from what I've read that even some expeditions as late as the 60s were expected to be successful, and indeed there were 1961 and 1968 expeditions which were taken seriously by 'mainstream' scientists. By the 1970s and 80s – when sightings were continuing and even increasing in number in some areas – it looked more likely that what was happening was a social phenomenon, not a zoological one... we're talking here about Tasmania alone, but of course things kicked off on the Australian mainland too.

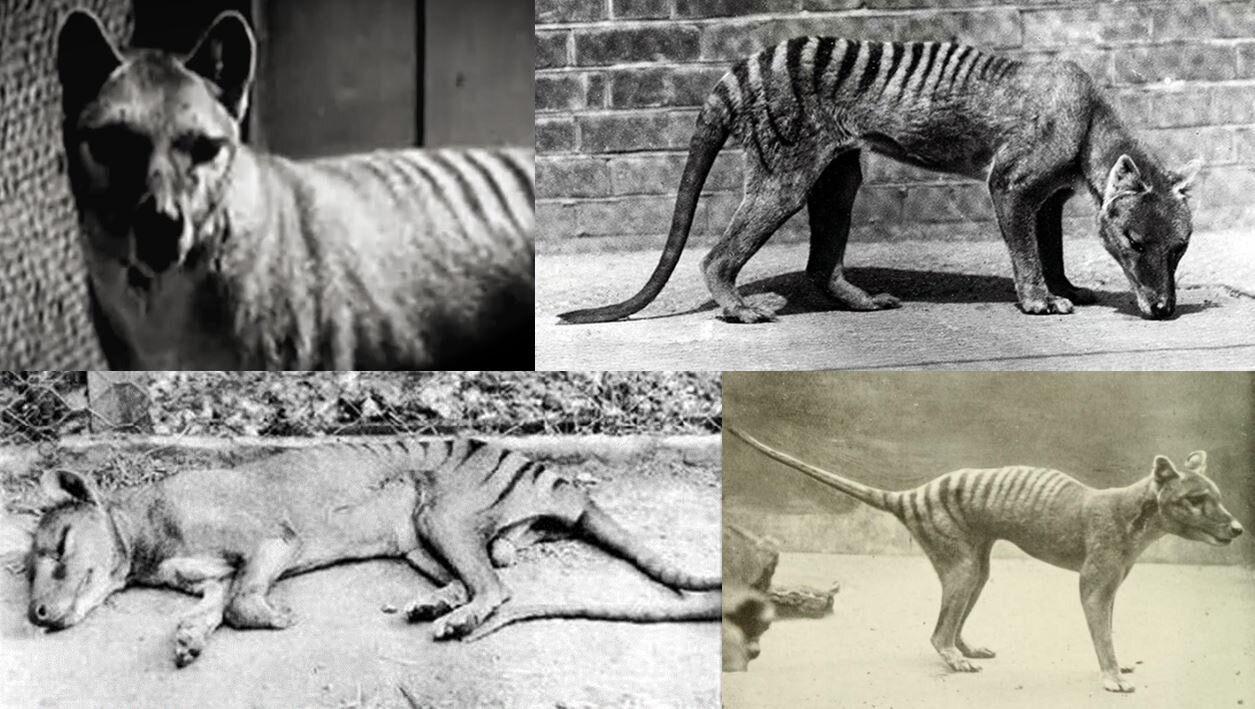

Caption: a montage of live, captive thylacines. The several claimed ‘living thylacine’ images (and bits of film) taken over the past five decades or so always fail to show the many key anatomical and proportional nuances of this highly distinctive animal. Images in public domain.

Why do people think they're still around? It's complex, but I don't buy any of this stuff about it being due to people being romantic, or aiming to allay guilt about causing the animal's extinction.... it all comes down to standards of evidence and where you think 'real expertise' lies. Just like with Nessie and any other mystery creature, there are a number of dodgy, vague reports which are – however poor – still 'good enough' to make some people think that the animal is still being seen. And the people who follow this idea of late survival tend (as a generalisation) to put more stock in amateur observers than relevant qualified scientists.

What's the story with Neil Waters and the Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia? It seems like they've made some pretty strong claims in the past--how have they responded to those claims being knocked down? Are they or have they ever been at all credible?

I can't pretend to know anything special about them. They seem to be an amateur group whose starting position is that thylacines persist, and that they're going to demonstrate it. Waters has made at least one previous claim of recording live thylacines, and it turned out to be a mistake. I see the group as similar to so many amateur 'monster hunters' worldwide: seemingly genuinely interested and with the best of intentions, but prepared to accept a very low standard of evidence as support for their favoured contention, and often dismissive of the more critical opinions that come from qualified experts. If you're obsessed with thylacines and their claimed persistence, it's likely that you're operating under what's known as 'expectant attention': every shadow, every rustle in the bush, every mid-sized animal is a potential thylacine. That's a dangerous mindset to be in, since it leads to frequent error and the over-interpretation of just about every observation.

Caption: the ‘thylacine’ images released by the Thylacine Awareness Group have been analysed by experts, and the animals they show have been identified as…. pademelons. Pademelons (this is a Tasmanian pademelon Thylogale billardierii) are small wallabies, mostly (but not universally) regarded as close kin of rock wallabies and tree kangaroos. Image: JJ Robinson, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

It seems like there's a fairly common pattern that plays out of people getting a bit of inconclusive footage and making hay out of it--I'm thinking of the Ivory Billed Woodpecker flap some years back. What are the mechanisms that make people so inclined to see cryptids in animals with mange, or somewhat unclear camera trap footage, or what have you? Is this partially a cultural thing, or are there psychological tricks at play as well? (Basically: what's the science behind why people see cryptids?)

For whatever reason, these sorts of people become strongly attached to the idea of a given creature existing or persisting. Sometimes this is because of a personal experience. Other times it's because they have confidence – perhaps misplaced over-confidence – in eyewitness testimony and anecdote. If you become committed to the pursuit of such a creature (be it a Thylacine, Ivory-bill or Bigfoot), especially when it's playing on your mind 24-7, then evidence that is, in reality, simply not good enough may become good enough to you. The individuals concerned are, in my experience, not sufficiently experienced in critical thinking or in understanding that building a case for something controversial and problematic requires you to present damn good evidence. In short, this is both cultural AND psychological... I'm struggling to describe it concisely, since we're talking here about the psychology of belief, which is a huge subject which touches on a massive range of topics (politics, religion and ideas about how the universe works).

Caption: how much does the hunt for Bigfoot or the Ivorybilled woodpecker hinge on wishful thinking or expectant attention? It’s a good question. Images: Darren Naish; Jerry A. Payne, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Followup: how much of this comes from even fairly outdoorsy people not being that intimately familiar with animals they share the landscape with?

This might be part of the story. When people who seemingly have a fair bit of outdoor smarts mistake familiar animals (like small wallabies) with far more exotic creatures (like thylacines), you do have to think that those individuals might not be sufficiently familiar with local wildlife. We all make mistakes: even the most experienced naturalists make misidentifications, sometimes hilarious ones. But the fact that this 'thylacine' claim had been made twice, with pademelon as the answer on both occasions, makes me think that we're seeing a combination of expectant attention, a lack of critical thinking skills, AND a fair bit of naivety.

Other than the case of the ivory-bill, are there other famous cases where people made a lot of fuss over images that weren't specifically hoaxes, but proved not to be what people hoped they were?

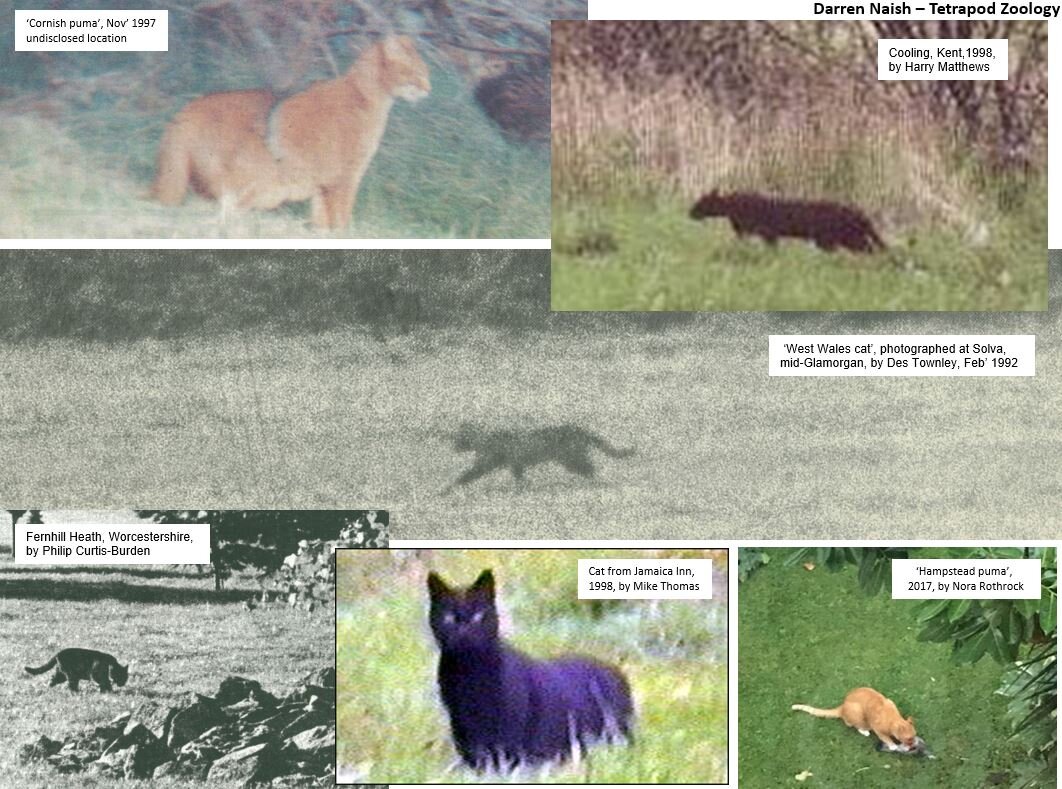

I'm struggling to think of something that's a close analogue for what we have here. The so-called 'chupacabras' (the dog-like version of the US mainland, not the humanoid original of Puerto Rico) might be an example. There are all those 'British big cat' photos which have turned out to be domestic cats. There's that Bornean 'lemur civet fox' animal which went viral for a few weeks but was most likely a misidentified squirrel.

Caption: people of all sorts make observational mistakes all the time. Some are more understandable, or acceptable, than others. I think - for reasons linked to physical, material evidence - that non-native large cat species live wild in the UK. But I also think, and am usually dismayed by, cases where people see or photograph domestic cats and identify them as pumas or panthers.

Where does the search for unknown populations of animals slip into pseudoscience and magical thinking? What are the harmful effects of keeping hope in thylacine survival alive, if there are any? (Aside from the possibility of grifters cashing in on it?)

In the case of alleged thylacine persistence, I don't think that the pseudoscience issue is relevant. So far, everyone interested (so far as I know) is thinking of these animals as... just as animals. No need for psychic powers or links with aliens or whatever. This happened with bigfoot and some other crypto-hominids because people have really struggled to work the accounts and observations into mainstream science.

What are the harmful effects of believing in persisting thylacines? A good question. I don't know, and have mixed feelings. It could be bad because it perhaps minimises or downplays the very real impact that humans are having, and have had, on the natural world. In other words: is it in the same league as denying climate change? Saying that the animal persists could encourage people to think that there's always hope, that things aren't that screwed up after all. On the other hand, I do think (as I said earlier) that the people behind these claims believe in these creatures because they've been swayed by anecdotes, or have had experiences themselves. And if they're championing discussion of, and study of, nature – and even calling for the preservation/conservation of relevant habitats and areas – it could be argued that they're not ‘bad’ at all, or in fact perhaps even.... a good thing. It's complex.

Caption: thylacine figures in my collection. Thylacines live on in several forms, but do they persist as live animals in the Australian wilderness? The evidence presented so far is not, alas, at all convincing….

For other TetZoo articles related to this one, see…

Rilla Martin’s 1964 photo of the ‘Ozenkadnook tiger’, August 2010

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Rilla Martin's Ozenkadnook Tiger Photo, Revisited, October 2016

The Ozenkadnook Tiger Photo Revealed as a Hoax, March 2017

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness, August 2019

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos, August 2020

Refs - -

Anon. 1985. Thylacine reports persist after 50 years. The ISC Newsletter 4 (4), 1-5.

Bailey, C. 2001. The thylacine lives, OK? BBC Wildlife 19 (8), 89.

Dash, M. 1992. The lost Australians. Fortean Times 62, 54-56.

Douglas, A. M. 1986. Tigers in Western Australia? New Scientist 110 (1505), 44-47.

Douglas, A. M. 1990. The thylacine: a case for current existence on mainland Australia. Cryptozoology 9, 13-25.

Greenwell, J. R. 1994. Who’s seen the thylacine? BBC Wildlife 12 (7), 48.

Healy, T. & Cropper, P. 1994. Out of the Shadows: Mystery Animals of Australia. Ironbark, Chippendale, Australia.

Rounsevell, D. E. & Smith, S. J. 1982. Recent alleged sightings of the thylacine (Marsupialia, Thylacinidae) in Tasmania. In Archer, M. (ed) Carnivorous Marsupials. Royal Zoological Society of new South Wales (Sydney), pp. 233-236.

Smith, M. 1982. Review of the thylacine (Marsupialia, Thylacinidae). In Archer, M. (ed) Carnivorous Marsupials. Royal Zoological Society of new South Wales (Sydney), pp. 237-253.