Among the most flamboyant and striking of South American birds are the two Rupicola species, known commonly as ‘cocks-of-the-rock’ (though it looks really odd seeing the name written as a plural like that).

Caption: the very first image of a cock-of-the-rock I ever recall seeing. From the cover of Charles Tunnicliffe’s Tropical Birds of 1960. This is one of the famously influential ‘tea card’ books, where you have to collect the cards to complete the book. Image: Darren Naish.

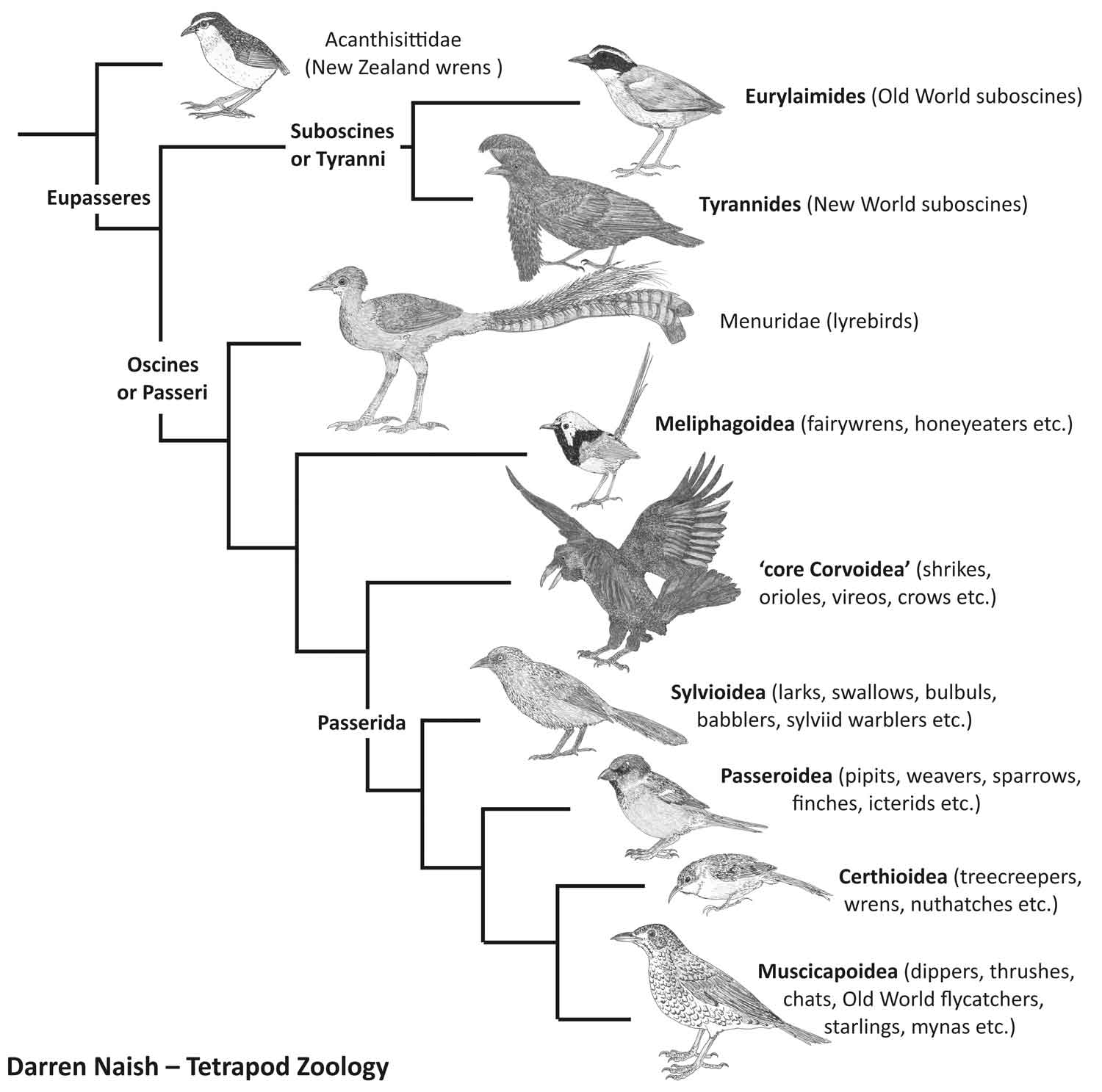

These two species – the Guianan cock-of-the-rock R. rupicola of the Guianan Shield and the Andean cock-of-the-rock R. peruvianus of the tropical Andes (from Venezuela in the north to Peru in the south) – are members of Cotingidae, a large group of South American passerines that’s part of Tyrannides or Tyrannida, a major clade within the suboscines. Suboscines (also called Tyranni) also includes the ovenbirds of the Americas, and the Old World pittas, broadbills and kin.

Caption: a much-simplified depiction of passerine phylogeny. Suboscines and oscines form the two great groups. This diagram is one of a huge number produced for my in-prep textbook on the vertebrate fossil record, on which go here. Image: Darren Naish.

I’m mostly writing about them because I’ve essentially never written about cotingas at TetZoo at all, nor about their close relatives (the tityras and kin, the manakins and so on). I have, however, written about an essential book on these birds: Guy Kirwan and Graeme Green’s 2011 Cotingas and Manakins, an indispensable work on these groups (my review is here, though it’s now missing all the images that originally made it fun to look at, SIGH).

Caption: if you’re seriously interested in cotingas and manakins (and their close kin), you should obtain Kirwan & Green (2011). It’s a brilliant book. Image: Christopher Helm.

Cocks-of-the-rock are unusual enough that they were regarded as worthy of their own family (Rupicolidae) until as recently as the 1970s. Details of the thigh arteries were thought by some experts to indicate possible closeness to tyrant-flycatchers rather than to cotingas but in several aspects of anatomy (like syringeal type), they’re fairly typical cotingas. In 1971, cotinga expert David Snow sent Charles Sibley a cock-of-the-rock egg collected from Guyana, the resulting experiments on the egg’s chemical composition proving, to Sibley’s satisfaction, that Rupicola should be included within Cotingidae (Snow 1973). More specifically, molecular data groups them with Phoenicircus (red cotingas) and perhaps with Snowornis (green pihas) in a clade that’s named Rupicolinae (Ohlson et al. 2007, Tello et al. 2009). It should be noted that Phoenicircus is sufficiently unusual for a cotinga – it has carotenoid-rich, saturated red plumage, fused third and fourth toes and a manakin-like gestalt – that it has at times been suggested, erroneously it seems, to be an ally of manakins (Snow 1973).

Caption: Guianan red cotinga (Phoenicircus carnifex) in hand. What a striking bird. Image: Etienne Littlefair, wikipedia, CC BY 2.5 (original here).

Cocks-of-the-rock are birds of tropical and subtropical montane forests, most typically those with rocky gorges and areas where there are caves and large boulders. Such places are crucial for nesting: the nests (which are made of mud, vegetation and a bit of saliva) are constructed on the vertical side of a cave or rock in a shaded location, often close to running water. Nesting is also semi-colonial (Kirwan & Green 2011). Having said that they’re montane forest birds, there’s a single record of a Guianan cock-of-the-rock in the northern savannahs of Surinam, this perhaps being the consequence of a long dry season that forced the bird to move. They’re otherwise mostly sedentary but are powerful, agile fliers.

Caption: images showing Rupicola in life virtually always show them in forested settings, but they also frequent caves, the walls of ravines, and boulder fields. These photos, showing a female Andean cock-of-the-rock at her nest and while elsewhere in a cave, were taken in the Cueva del Higueron, Peru. Images: JYB Devot, wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0 (originals here and here).

Both Rupicola species are large as cotingas go, with males reaching 33-34 cm in total, and they’re spectacularly red or orange. Sexual dimorphism is pronounced, the most obvious differences involving the big, fan-shaped dorsal crests of males. The crest is formed of two rows of feathers that are in close contact along their middle surfaces. In the Guianan R. rupicola, silky filaments emerge from the rump and back and trail from and over the animal’s sides. Females are darker and browner than males and with a crest that’s more of a tuft than a giant dorsal fan. Both species are lek breeders, the Andean species perching on lianas and other structures some metres off the ground while the Guianan species does its displaying on the ground.

Caption: male Guianan cock-of-the-rock, showing characteristic filaments and ‘orange peel’-like feathers on the back. Image: Aisse Gaertner, wikipedia, CC BY SA 4.0 (original here).

Numerous vocalisations – some likened to chicken crowing and cat meowing, there’s also a bugling ‘assembly call’ – are made at the leks, and also while foraging and when calling attention to the sighting of a predator. A modified tenth primary feather is used by the Guianan species to make a whistling noise.

Caption: male captive Andean cock-of-the-rock, photographed at San Diego Zoo. The lush black wings and lack of trailing filaments make this species look very different from the Guianan species. Not all Andean cocks-of-the-rock are the same: there are at least four distinct populations, conventionally identified as subspecies. Image: Jerry Thompson, CC BY 2.0, wikipedia (original here).

The bill is long, broad-based and slightly hooked but usually mostly hidden by the crest. It’s used to procure both fruit as well as arthropods and small vertebrates. While these birds are best characterised as frugivorous, it’s interesting that they also catch and eat frogs, lizards and small snakes and such items are said to be important in the diet of nestlings (Kirwan & Green 2011). Mice have been eaten by captive Andean cock-of-the-rock. Such raptors as hawk-eagles, accipiters and forest falcons are known to prey on Rupicola (Kirwan & Green 2011). UPDATE: there are also observations of them chasing and eating small passerines, and this might even be a regular habit (Mahecha et al. 2018). Thanks to Max Kirsch for passing on this information.

Caption: male Guianan cock-of-the-rock, in a pose which allows us to see the length of the bill through the lower part of the fan of feathers. Note that this individual is missing part of one of his toes. Image: Juniorgirotto, wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

In combining frugivory with large size, marked sexual dimorphism and especially elaborate sexual displays, cocks-of-the-rock are ‘extreme’ cotingas, superficially similar to the distantly related bellbirds (Snow 1973), and in some ways suboscine ‘equivalents’ of the even more distantly related birds-of-paradise (Kirwan & Green 2011).

Caption: museum specimens of Rupicola don’t fare well after decades in sunlight, it seems. I’ve never seen a live cock-of-the-rock… so far, only museum specimens like this Guianan one. Image: Darren Naish.

Needless to say, there’s tons more to say about cotingas and their allies, but this, at least, is a start.

For previous TetZoo articles on passerines (concentrating, once again, on the few articles that haven’t been destroyed via the removal of their images), see…

Great tits: still murderous, rapacious, flesh-rending predators!, February 2013

For The Love of Crows, October 2015

Thoughts on the Passerine Tree, 2016, October 2016

A Battle Among Blue Tits, February 2018

Refs - -

Kirwan, G. & Green, G. 2011. Cotingas and Manakins. Christopher Helm, London.

Mahecha, L., Villabona, N., Sierra, L., Ocampo, D. & Laverde-R., O. 2018. The Andean Cock-of-the-rock (Rupicola peruvianus) is a frugivorous bird predator. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 130, 558-560.

Ohlson, J., Prum, R. O. & Ericson, P. G. P. 2007. A molecular phylogeny of the cotingas (Aves: Cotingidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42, 25-37.

Snow, D. W., 1973. The classification of the Cotingidae (Aves). Breviora 409, 1-27.

Tello, J. G., Moyle, R. G. Marchese, D. J. & Cracraft, J. 2009. Phylogeny and phylogenetic classification of the tyrant flycatchers, cotingas, manakins, and their allies. Cladistics 25, 429-467.