I’m a big fan of Godzilla, and of kaiju movies in general. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that I just went and saw Godzilla: King of the Monsters (KOTM), and – boy – did I like it. I don’t care about criticisms concerning the human plot (which I thought was fine, perfectly serviceable and well-acted), nor do I care that various possible plot-holes perhaps create issues. Look, it’s a film about giant monsters - rebranded titans for KOTM - knocking the crap out of each other, stomping on cities, out-flying military jets and messing about with lava, ice, epic weather, electricity and nuclear power. I loved it, and I applaud the bravery of the team concerned in taking classic monsters like King Ghidorah and remaining mostly faithful to their design without the need for some major overhaul.

A main theme of Godzilla: King of the Monsters is that humanity is an infection upon the planet, and that titans are the cure. Image: (c) Warner Bros.

I noticed a lot of interesting trivial little details in the film that are of interest or relevance to readers of this blog, at least some of which will have been missed unless you’re a monster fan or have serious nerdy interests in zoology. I mean, there are a hundred other things that are references to other stuff relevant to the Godzilla films and their real-world, factual backstory (Serizawa’s watch, the reference to a Steve Martin, Castle Bravo, Infant Island, maser turrets, the term ‘Monster Zero’, the use of a frikkin’ oxygen destroyer… and so on). It’s the more zoology-themed things I mostly want to highlight here.

The ‘science of Godzilla’ has been covered a fair bit at TetZoo in the past… Image: The Biological Nature of Godzilla.

I should add that Godzilla has been covered at TetZoo on several previous occasions, the usual caveat being that these classic articles (which got a fair bit of attention back in the day and have led to various media appearances and such concerning ‘The Science of Godzilla’) have recently been effectively ruined by the removal of their accompanying images. They’re linked to below.

One more thing. STOP READING NOW IF YOU WANT TO AVOID SPOILERS. THERE WILL BE SPOILERS. Ok, onwards…

Figures in my collection. As a Godzilla fan, it’s great that at least some of these characters have been licensed anew for a modern movie franchise. Image: Darren Naish.

Musical Tunes. The score to this movie – by composer Bear McCreary – was fantastic, and hopefully you noticed that the main monster characters had their own musical themes. These themes incorporated components of the original themes created for the monsters in the original Toho movies. I mean, Godzilla’s theme is from the original 1954 movie and Mothra’s is from the 1962 debut movie, my god. This could partly be considered fan-service but more appropriately reflects an effort to create continuity with these older works. If you liked the music, stay to the end of the credits. There’s a post-credits scenes, by the way, and one that I didn’t predict.

Montage of the main monsters - re-branded as titans for this movie - starring in Godzilla: King of the Monsters. Image: (c) Film Music Central (original here).

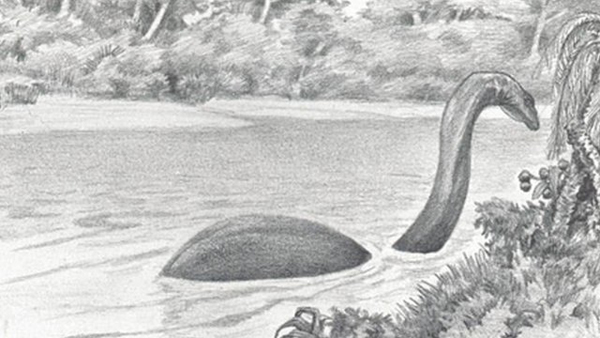

Frank Searle’s Nessie. At one point in KOTM, people sift through images when learning about the long cultural influence King Ghidorah has had on human civilizations over the centuries. Among the images we see – ever so briefly – a blurry black and white photo of a water monster, its head obscured because its long, slender neck curves down to the water. This is unmistakeably one of Frank Searle’s infamous Nessie photos. Searle (1921-2005) was a notorious Loch Ness Monster investigator who, between about 1969 and 1983, claimed to have photographed the beast on a great many occasions (over 20; Harrison 1999), often at very close range. As should have been obvious right from the start (amazingly, he was able to dupe some people into thinking that he was the real deal), his photos variously involved models, cleverly posed sticks and branches, and even artwork superimposed onto photos of the water surface. He would likely have been thrilled to see one of his photos appear in a big-budget movie.

One of Frank Searle’s (in)famous Nessie photos. I’m 99% sure that this exact image made a brief appearance in KOTM. Image: (c) Frank Searle.

The Alpha Myth. Main human character Dr Mark Russell is a biologist who’s spent years studying wolves and other animals. In attempting to explain the combative, competitive, hierarchical behaviour observed among the newly emerging titans, he explains that they’re working out which will serve as The Alpha, the big boss animal that gets to control the others. He starts this discussion by saying that animals like wolves work within such a structure, ‘The Alpha’ being the biggest, strongest and meanest and thus the one that gets to rule the pack. This idea is deeply rooted and mainstream in culture and even integral to the philosophy of some animal trainers. But it’s not quite right. Wolf packs are extended families, with the leaders (which can still be called alphas if you want) being the parents of most other pack members. They are thus the most experienced, wisest wolves, not necessarily the baddest or strongest.

Check out all the interesting body language going on in this captive wolf pack. The especially dark animal near the middle is presumably an ‘alpha’. Image: Darren Naish.

I know that this ‘Alpha’ concept was integral to the movie and works fine as an explanation for what we see of titan behaviour. But it would have been nicer if a person who’s supposed to be an experienced biologist said things that better reflected current thinking on the species he was supposed to know best.

The Congolese Titan. At several points during the film, we see world maps which depict titan activity as it’s happening live. And if we look at central Africa during one such scene, we see that the titan stomping around in the Congo region is labelled ‘mokele-mbembe’. Yes, the mokele-mbembe, the long-necked water monster of the Congo, beloved of cryptozoologists and creationists and suggested on many occasions to perhaps be a living sauropod dinosaur. Mokele-mbembe as we ‘know’ it (I mean: as described in the cryptozoology literature) wouldn’t make a particularly impressive titan, since it’s only meant to be about elephant-sized (albeit with a longer neck and tail). The KOTM version is presumably a super-sized version then. I’ve written about mokele-mbembe several times at TetZoo, and also in my book Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017).

One of the most famous of mystery beasts: mokele-mbembe, a creature popularly suggested to be a modern-day amphibious sauropod dinosaur. This illustration is by David Miller for Roy Mackal’s 1987 book on the subject. Image: David Miller/Mackal 1987.

Our Species Name. A reveal in the movie is that palaeobiologist and kaiju scientist Dr Emma Russell has used acoustic data from a mystery species in designing the sounds emitted by the monster-luring ORCA device… aaaand, the mystery species is us, since we’re one of the biggest monsters. What name do they give our species? They have it written – very clearly and in big red letters – ‘Homo sapien’. Major fail, 10 points deducted. It’s difficult to work out why, but many people today seem to think that ‘Homo sapien’ is the correct technical name for our species, and it’s often said this way in TV shows and popular literature. Our scientific name is Homo sapiens, which is scientific knowledge about as advanced as knowing that water has the formula H2O or that the Earth is a sphere.

That’s Not How You Do Scientific Names. On a related note, the titans in the movie have what look like scientific names. But the names don’t make any sense as goes the conventions biologists actually use in naming organisms. I think we’re meant to think that the names we see in KOTM are species names, unique to each kind of titan. These are obviously novel: hypothetically, Godzilla could be something like Gojiratitan terribilis, while Rodan might be, let’s say, Stupendadactylus mexicanus. But KOTM puts all the titans in the same one genus – Titanus (which isn’t available in use since it’s already been used for something else*) – which is then followed by a specific epithet, such that Godzilla is Titanus gojira, Rodan is Titanus rodan and so on. Most viewers won’t care about this, but it’s something that anyone with any knowledge of biology will notice and it’s annoying and a bit dumb. Next time: have an actual biologist on hand to check for these sorts of technical things, they make movies better!

* The longhorn beetle Titanus Audinet-Serville, 1832.

Oh Hollywood, why you no do scientific names right? This image is not from a Godzilla film… Image: (c) Universal Pictures.

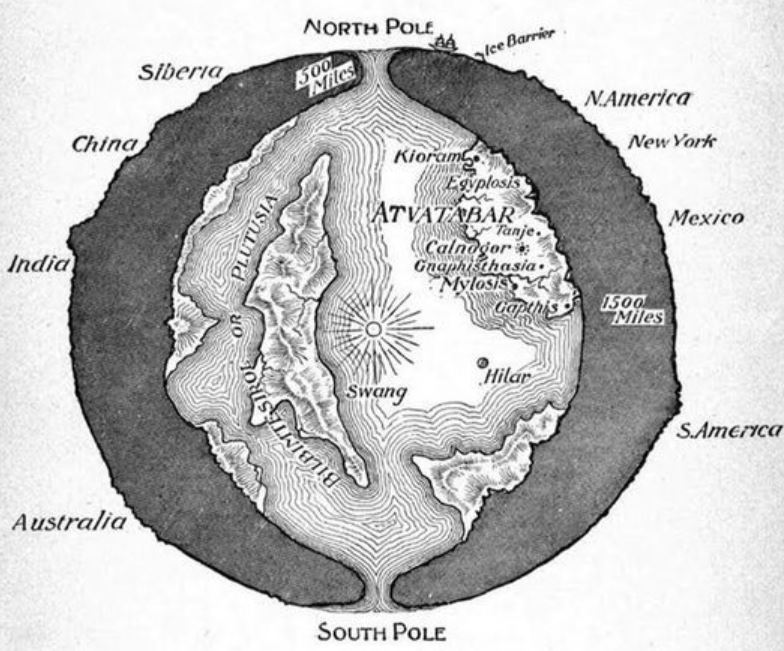

The Hollow Earth. KOTM goes big-time with the idea – previously hinted at in Kong: Skull Island – that our planet is a honeycomb, with hidden tunnels that pass right through it and gargantuan internal chambers and pockets (a description most familiar to modern audiences due to the form of the planet Naboo in Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menance). I suppose that this has been worked into the MonsterVerse as a way of explaining how the impossibly huge yet also cryptic titans can remain concealed for a long time and only emerge on occasion.

Here’s the ‘Hollow Earth’ image that appears most frequently online (this being because it was uploaded to wikipedia). It’s from William Bradshaw’s 1892 novel The Goddess of Atvatabar. Image: public domain, original here.

The Hollow Earth thing is not unique to the MonsterVerse: it was suggested, as a serious model for our planet’s structure, by Edmond Halley in 1692. Halley didn’t propose the model because it was a fun idea, but because he thought it might explain anomalous compass readings which, he thought, meant that the Earth was formed of more than one rotating sphere. His assumption that compass readings should always be consistent was flawed, since they vary given that the magnetic field is constantly in flux. This model – which involved substantial gas-filled spaces existing between the different sphere – was dead and disproven by the late 1700s, and thereafter it only survived in pseudoscience (UFOs must come from inside the Earth instead of from outer space, and so on) and fiction. Edgar Rice Burroughs is most famous for using the Hollow Earth model for his Pellucidar novels of the early 1900s. These have people tunnelling into the Earth and discovering a hidden world, lit by an inner sun, inhabited by creatures long thought extinct. It’s surprising and interesting to see this idea persist in a modern sci-fi movie series.

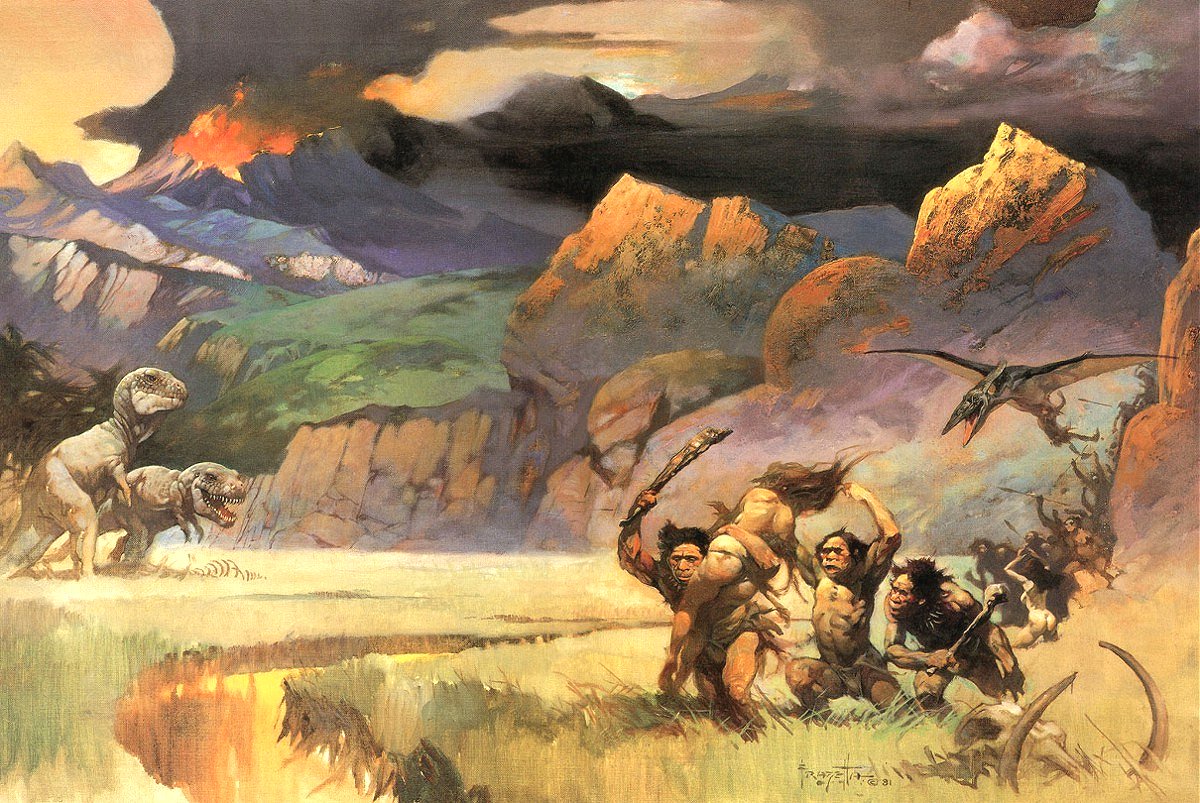

The Hollow Earth of Edgar Rice Burroughs is supposed to have looked something like this… [UPDATE: nope, this is nothing to do with the Hollow Earth - it was instead done for the cover of a 1967 magazine issue that celebrated the movie One Million Years BC. Thanks to Alan Friswell for this correction]. This is one of Frank Frazetta’s inimitable illustrations. Image: (c) Frank Frazetta, original here.

That Final Meltdown. Without giving too much away (I know I said that there would be spoilers, but…), the final act of the movie involves Big G discharging A LOT of nuclear energy, so much that he glows red and seems in imminent danger of incandescent eruption. If you’re a hardcore Godzilla fan you may well be predicting at this point that KOTM was going to do its own take on the final scene of the 1995 Godzilla vs Destoroyah (aka Godzilla vs Destroyer) in which Godzilla glows with radiation and eventually (spoiler) melts and dies – only to be replaced by his direct descendant, Godzilla Junior. I don’t know if the KOTM team were inspired by Godzilla vs Destoroyah at all, or if what they did was wholly novel, but the similarities are hard not to notice.

In the 1995 movie Godzilla vs Destoroyah, Godzilla burns up from the inside and endures a painful phase of looking spectacularly patchworked with glowing red. Images: (c) Toho.

Rick and Morty. You might have noticed the prominent Rick Sanchez sticker on the lid of a laptop (if, that is, you’re a Rick and Morty fan. I am). This may or may not be a nod to the fact that Bradley Whitford’s character Dr Rick Stanton was apparently inspired by Rick of Rick and Morty. While I’m here, the original concept of Rick and Morty was based on Doc and Marty of Back to the Future… which is also heavily referenced – or, hell, flat-out mentioned – in another big movie of 2019. A little movie that hasn’t done at all well at the box office.

Finally – Character Continuity. Many of the people in KOTM were previously introduced in 2014’s Godzilla, and therein we got their various backstories (Dr Serizawa, for example, is the descendant of Daisuke Serizawa from the original movie of 1954). But note that they also featured characters who have a direct link to other Godzilla and MonsterVerse movies. The Chen twins – both played by Zhang Ziyi – were an obvious nod to the twin fairies of the 1961 Mothra movie, and Dr Houston Brooks (played in KOTM by Joe Morton, who we mostly know as Dr Myles Bennett Dyson) previously appeared in Kong: Skull Island.

A strength of the new Legendary Godzilla movies is they establish an approximate continuity with the original film of 1954. To go a different route and start Godzilla afresh, I think, is a big mistake. Image: (c) Toho Studios.

And we’ll end this here, I hope you found it interesting. Do you like monsters? Do you like Godzilla? If yes, go and watch this movie. I might go see it again.

For the previous Godzilla-themed TetZoo articles, see…

The science of Godzilla, February 2007

The science of Godzilla, 2010, November 2010

The anatomy of Zilla, the TriStar 'Godzilla', November 2010

Refs - -

Harrison, P. 1999. The Encyclopedia of the Loch Ness Monster. Robert Hale Ltd, London.

Mackal, R. P. 1987. A Living Dinosaur? In Search of Mokele-Mbembe. E. J. Brill, Leiden.