It starts with the dragging off of a lamb. It ends with bearmadillos.

Caption: this footage - from Argentina - shows an armadillo biting a lamb and clawing at its neck, then grabbing the animal by the ear and dragging it off for some distance. The footage ends when the farmer doing the filming steps on the armadillo. See if for yourself here.

I’m a huge fan of armadillos: they’re among my favourite mammals and, while I’ve written about them a few times (see links below), I’ve never covered them in all that much detail. I’ve just never found the time. If you move in the same social media circles that I do (god help you), you might have seen the very exciting and interesting video clip which shows a Six-banded or Yellow armadillo Euphractus sexcinctus attacking, killing and dragging off a lamb (as in: a baby domestic sheep Ovis aries).

A second clip, circulated by some youtubers in connection with the one featuring the lamb, shows an armadillo (also a Six-banded armadillo? I’m not sure) attacking a calf (as in, a baby domestic cow Bos taurus) with what looks like predatory intent. In this case, the armadillo is raking at the cow’s belly with its forelimbs, and perhaps biting it too. The calf is not very happy about this and is attempting, unsuccessfully, to get back to its feet. The footage first circulated in June 2019 and was taken in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina. The farmer who owned the land said that three dead calves, with their entrails hanging out, had previously been discovered at the same location.

Caption: blurry screenshot of armadillo attacking calf, my attempt at clarifying things at right. Again, the footage stops when the person doing the filming puts their booted foot on the armadillo. They then lift it by the tail. See the original footage here.

Understandably, this behaviour has surprised many of its viewers, most of whom are clearly learning for the first time that various of the larger armadillos can and will attack animals this big. Let’s go on a meandering tour of armadillo feeding habits and see where we end up…

First off, predation of this sort is not news if you know a lot about armadillos. Euphractus in particular is well known for occasional predation, or attempted predation, on relatively big vertebrates. Dalponte & Tavares-Filho (2004), for example, report observations where captive Euphractus were seen “attacking a live deer fawn” (the deer was a Grey brocket Mazama gouazoubira) as well as a young rhea, and in both instances the armadillos tried to drag these animals away to their burrows.

Caption: a rather… imaginative… portrayal of armadillo vs brocket deer predation. I don’t think it really happened like this, but it would be cool if it did. Image: Darren Naish.

Among the most familiar of armadillos are the long-nosed Dasypus species, a group often characterised as insectivores. After all, they have long, slender noses, a lightly built lower jaw, small teeth, a long, slender tongue, and are known to eat large quantities of ants and termites. It’s generally expected of ‘insectivorous’ animals that the adaptations which make them insectivorous are easily co-opted for predation on small vertebrates, and such it is with armadillos. Several species are well known for their predatory tendencies, their diet including a list of small vertebrates – frogs, lizards, snakes, rodents and small marsupials – which they kill with their teeth and large, pointed claws. Some species also use their tough exterior as a weapon: Chaetophractus species are reported to use the edge of the shell to kill snakes (Nowak 1999) which are then eaten. Captive Six-banded armadillos have killed large rats, though “they are inefficient predators” which “tear apart a carcass by standing on it and ripping off pieces held in their jaws” (Smith & Redford 1990, p. 31).

Caption: this graph from Gallo et al. (2019), which reports armadillo diet in Argentina, shows how significant vertebrate prey are in the diets of some armadillo species.

In fact, while armadillos are often described or characterised as ‘insectivores’ (especially in popular books), this isn’t accurate for them all, and they’re better described as ‘specialised insectivores’ (Cabassous and the Giant armadillo Priodontes maximus are examples, though hold that thought), ‘generalist insectivores’ (some Dasypus species and Tolypeutes are examples), and ‘omnivore-carnivores’ (the Chaetophractus hairy armadillos are examples, as is Euphractus and the Pichi Zaedyus pichi) (Redford 1985).

Caption: everyone’s favourite armadillo, the Nine-banded Dasypus novemcinctus. Despite its name it’s variable in band number. Images: Ereenegee, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Hans Stieglitz, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Yes, so widespread within armadillos are vertebrate-eating habits that most members of the group are actually better characterised as generalists rather than as insectivores. And an interesting point which I’ve had reason to mention more than once is that this even goes for those species that appear (on anatomy alone) to be highly specialised insectivores. Smith & Redford (1990) showed how the Nine-banded armadillo D. novemcinctus – a species which, from an anatomical point of view, is very much a specialised myrmecophage (an ant/termite specialist) – is actually a generalist or opportunist across a great part of its range, essentially eating anything edible it encounters. This includes seeds, berries, fungi, crayfish, small mammals, amphibians and reptiles. This is an excellent example of the “anatomy is not destiny” mantra (Smith & Redford 1990); the fact that some animals don’t live by the rules we would predict on the basis of their anatomy.

Caption: Pichi Zaedyus pichi, a small armadillo of southern South America, and the only species which undergoes hibernation. Image: Mikelzubi, CC BY 3.0 (original here).

Ok, a caveat to this case is that the ‘most generalised’ Nine-banded armadillo populations are those which inhabit North America, a region the species has only recently moved into. The feeding ecology of these North American animals may perhaps be a response to unusual conditions, like a comparative rarity of its preferred prey or an absence of competitor species, and not a simple indicator of ecological flexibility (Smith & Redford 1990). However, the Nine-banded armadillo isn’t the only example of this sort of thing; read on.

Anyway… it’s also ‘easy’, in evolutionary terms, for ‘insectivores’ like the species discussed here to also take to the exploitation of carcasses. Here’s where we come to some particularly appealing tales, anecdotes and observations, since armadillos of several species are well known for taking advantage of carrion as and when they can.

Caption: Euphractus. There’s supposed to be six subspecies, which vary in how hairy they are. Image: Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

The Six-banded or Yellow armadillo is especially renowned for its tendency to eat carrion and “the only time large numbers of Euphractus are seen together is when they gather around the carcass of a dead animal, where they feed on maggots and bits of meat” (Nowak 1999, p. 160). Incidentally, a popular idea which has arisen many times worldwide is that animals seen at carcasses are there to eat the maggots. Maybe sometimes it’s true, but I bet that some of the time it’s not, and that people have misunderstood carrion-eating. Pig skin and plates from armadillos (species uncertain) have been discovered as stomach contents in Euphractus and the presence of Yellow armadillos in areas of Brazil where vertebrate roadkill is especially abundant suggest regular carrion-feeding in this species (Dalponte & Tavares-Filho 2004).

Caption: at left, a Euphractus skull; generalised enough for the consumption of invertebrates, plants, carrions and even decent-sized vertebrates. At right: front view of a Euphractus. It’s hard to get good information on armadillo hands and feet, which makes this image useful. Images: Klaus Rassinger and Gerhard Cammerer, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Exlibris, CC BY-SA 2.5. (original here).

Euphractus isn’t the only carrion-eating armadillo: it’s also on record for the Pink fairy armadillo Chlamyphorus truncatus, Pichi, Screaming hairy armadillo C. vellerosus, Big hairy armadillo C. villosus and…. that ‘specialised insectivore’ the Giant armadillo (Smith & Redford 1990, Nowak 1999, Meritt 2006, McDonough & Loughry 2003, Gallo et al. 2019). Yes, another armadillos with a suite of adaptations for myrmecophagy is actually flexible and adaptable enough to do something that’s totally different on occasion, and this time it can’t be linked to its finding itself within unusual ecological conditions or whatever. Oh, and -- needless to say, any animal which removes carrion from an environment is a really useful animal to have around; it’s working as an ‘ecosystem service provider’.

Caption: an entirely hypothetical cartoon which speaks for itself. The armadillo is Priodontes, and it’s holding a human radius. Image: Darren Naish.

That’s great, but the fact remains that carcass consumption isn’t seen as a particularly endearing trait by humans. Redford (1985) and Smith (2007) noted that some armadillo species – normally considered desirable objects for the pot – aren’t eaten by people in some regions because their necrophagous habits make them undesirable. And it isn’t surprising that this habit in armadillos has led to various concerns and superstitions: the idea that armadillos might excavate graves and consume the recently deceased is present in several areas, most famously in the Paraguayan Chaco. There are also all kinds of rumours about armadillos being especially abundant, or especially plump and healthy, in or near cemeteries. They’re referred to as ‘gravediggers’ in some regions and dialects.

The general take on these accounts is that they’re based on tall tales or on sightings of armadillos digging in recently dug soil in graveyards, and shouldn’t be taken seriously. Well, maybe. I can easily believe that an armadillo – especially a big, chunky species like a Euphractus – could and would take advantage of human remains if the opportunity arose, and the suggestion has been made that ideas about corpse-eating in Euphractus might have originated following observations of these animals feeding on human corpses during wartime (Smith 2007).

Caption: Priodontes, the giant armadillo. In this case, a museum specimen in Prague. Image: public domain (original here).

The takehome from a lot of the stuff we’ve seen so far is that armadillos of several lineages are ‘flexible’ enough in anatomy and ecology to potentially evolve beyond the stage of omnivorous generalist and actually become properly predatory, aka faunivorous or animalivorous. And if you know anything about the armadillos we know as fossils, you’ll be aware that this seemingly already happened. Yes, there were truly predatory armadillos in the geological past… probably.

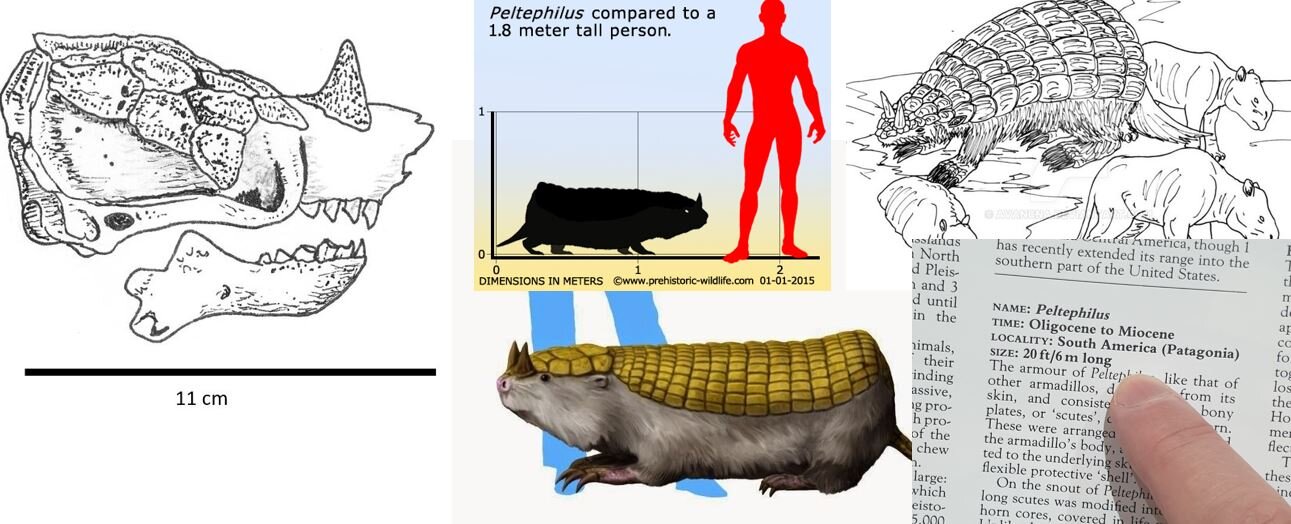

First things first, the fossil armadillos most often said to be predatory very likely weren’t. I speak, of course, of Peltephilus and its kin, the peltephilines or peltephilids, a group of Eocene, Oligocene and Miocene armadillos often dubbed ‘horned armadillos’ due to the paired, horn-like plates on their snouts. Peltephilines (which appear to be outside the clade that includes all other armadillos, glyptodonts and so on) are much like conventional armadillos in many aspects but their prominent teeth led famed Argentine palaeontologist Florentino Ameghino to consider them predators of other mammals. Ameghino also thought that peltephiline coprolites provided support for this view… buuut the coprolites he had in mind turned out to be fossilised seeds (Vizcaíno & Fariña 1997).

Caption: there’s a long history of the fossil armadillo Peltephilus being wrongly sized. Even some technical literature screws up the scale bars, making it look at if its skull is a massive 25 cm long. Nope, 11 cm skull length, so whole animal was not more than 1 metre long. The images and text shown here is, therefore, all erroneous (no disrespect intended to relevant authors and artists). The actual appearance of the whole animal is also something artists have been confused about, I especially love the images which make it look like a giant fairy armadillo! Images: skull by Darren Naish; prehistoric-wildlife.com; (c) Nobu Tamura (original here); avancna (deviantart page here); Cox et al. 1988.

Incidentally, I’ve always loved the fact that a popular and familiar book on prehistoric animals – the multi-authored Macmillan Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life (Cox et al. 1988) – describes Peltephilus as 6 metres (20 ft) long. As appealing as the concept of a Megatherium-sized armadillo may be, I regret that this is mistake, and that Peltephilus was actually less than 1 metre long.

The anatomy and functional morphology of this group was analysed anew by Vizcaíno & Fariña (1997). Rather than having jaws and a dentition specialised for the eating of vertebrates, Vizcaíno & Fariña (1997) argued that the relatively long jaws, the position of the longest teeth (they’re at the front of the jaws, not at the mid-length point or the back) and adaptations for digging suggest that peltephilines were burrowers which consumed items like plant tubers. While I agree with Vizcaíno and Fariña’s main point – which is that peltephilines were not specialised predators of vertebrates – it should be noted that their generalised anatomy still implies that they could have eaten small vertebrates and carrion, at least on occasion.

Caption: the very impressive skull of Macroeuphractus outesi, as figured by Vizcaíno & De Iuliis (2003); the original illustrations are from an 1894 monograph by Richard Lydekker. Frustratingly, the scale bar is not explained in the accompanying caption. It’s presumably 10 cm though.

This isn’t the end of the story. There are plenty of other fossil armadillos, some of which look to have been actual predators. Euphractus has what’s long been interpreted as a big cousin: Macroeuphractus from the Pliocene of Argentina (it turns out that Macroeuphractus may not be especially close to Euphractus at all, but we don’t need to worry about that for now). With a skull about 26 cm long, it must have had a total length of about 1.25 m and weighed over 30 kg (there are suggestions that it weighed over 100 kg but I have a suspicion that they’re based on old and incorrect statements about the weight of the modern Giant armadillo). While Macroeuphractus seems to have been superficially Euphractus-like overall, important differences include enlarged caniniform teeth in the upper jaw, a more robust dentition overall, a deeper rostrum, and enlarged temporal muscles. Vizcaíno & De Iuliis (2003) analysed these features in concert with a biomechanical study of jaw strength and concluded that this giant could certainly have been a carrion eater but also an active predator of other mammals, most likely caviomorph rodents and small notoungulates (both of which were abundant where it lived). I like very much the fact that their paper includes the possibly terrifying reconstruction you see here. A subsequent study used FEA (finite element analysis) to examine stress dissipation in armadillo jaws. The results on Macroeuphractus are somewhat difficult to interpret, but the authors weren’t able to rule out a predatory lifestyle (Serrano-Fochs et al. 2015).

Caption: Vizcaíno & De Iuliis’s (2003) reconstruction of a hunting Macroeuphractus. The idea here is that the armadillo is about to break into a burrow inhabited by cute little juveniles of the chinchillid rodent Lagostomus. The artwork was produced by one of the authors.

And that just about brings us to the end of this discussion. Except for one thing. Armadillos have given rise to large, robustly constructed predators before. Today, some of them are generalised enough, adaptable enough and formidable enough that they, too, can turn their proverbial hand to the scavenging of vertebrate corpses and even the predation of relatively big animals. So… in a future world, where adaptable, formidable armadillos persist – we can but hope – could there be the development of some new lineage of large, formidable predator-armadillos, their success perhaps fuelled by their ability to consume just about anything edible, and also by the decline and extinction of more specialised American predators? Mette Aumala – SpecZoo artist extraordinaire – has considered exactly this, and... world … I give you… BEARMADILLO.

Caption: Mette Aumala’s speculative Bearmadillo, used with permission.

For previous TetZoo articles on armadillos, see…

Five things you didn’t know about armadillos, June 2007

I, Priodontes, the tatuasu, September 2008

Refs - -

Dalponte, J. C. & Tavares-Filho, J. A. 2004. Diet of the Yellow armadillo, Euphractus sexcinctus, in south-central Brazil. Edentata 2004 (6), 37-41.

Gallo, J. A., Fasola, L. & Abba, A. M. 2019. Armadillos as natural pest control? Food habits of five armadillo species in Argentina. Mastozoología Neotropical 26, 117-127.

McDonough, C. M. & Loughry, W. J. & Loughry, W. J. 2003. Armadillos (Dasypodidae). In Hutchins, M. (ed) Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia Vol. 13: Mammals II, pp. 181-192.

Meritt, D. A. 2006. Research questions on the behavior and ecology of the Giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus). Edentata 2006 (7), 30-33.

Redford, K. H. 1985. Food habits of armadillos (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). In Montgomery, G. G. (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., pp. 429-437.

Smith, K. K. & Redford, K. H. 1990. The anatomy and function of the feeding apparatus in two armadillos (Dasypoda): anatomy is not destiny. Journal of Zoology 222, 27-47.

Smith, P. 2007. Six-banded armadillo Euphractus sexcinctus. Handbook of the Mammals of Paraguay 5, 1-16.

Vizcaíno, S. F. & De Iuliis, G. 2003. Evidence for advanced carnivory in fossil armadillos (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). Paleobiology 29, 123-138.

Vizcaíno, S. F. & Fariña, R. A. 1997. Diet and locomotion of the armadillo Peltephilus: a new view. Lethaia 30, 79-86.