I’ve written before about books that influenced me a great deal, and today I want to talk about a book that I remember very fondly from childhood. It’s All About Monsters by Carey Miller, part of the Usborne ‘The World of the Unknown’ series, published in 1977 (Miller 1977). If you know this book as well as I do, you’ll already remember it and know how good it is. If not, prepare for a treat… if, that is, you like beautifully illustrated children’s books on monsters.

Miller’s All About Monsters is a slim paperback, 32 pages long. It covers monsters from mythology, prehistoric monsters (because why not), sea monsters, and monsters of today (read: cryptozoology for kids). The text is fine – as you’d expect for Usborne, one of the world’s leading publishers of children’s books – but it’s the art that really makes this a wonderful book for me. The credits tell us that John Francis, Malcolm McGregor, Michael Roffe, Christine Howes and Mike Baber illustrated the book, with Francis being the creator of the majority of pieces. Check out the illustration on the cover, shown above. The juxtaposition of a terrifying giant predatory aquatic reptile with a manicured, very ‘British’ landscape is striking, memorable, and exciting.

Caption: the Monongahela monster, illustrated as if we actually knew what it looked like: a thick-bodied, serpentine creature that swam with a spiralling action and had homodont, conical teeth. The art throughout the book is fantastic. Image: John Francis/Usborne/Miller 1977.

In keeping with the vibe of conventional monster books – they describe monsters as if they might be real and awaiting scientific discovery – Miller’s book recounts several famous anecdotes and stories as if they’re ‘true’. A ‘serpents in the sea’ spread, for example, discusses the Monongahela report of 1852 (today mostly regarded as a hoax: Roesch 1997), the 1881 Bertie account (in which a group of North Sea fisherman had a frightening encounter with a seaweed-draped monster that glared at them with terrifying eyes) and, best of all, the 1962 Florida account in which five American Air Force skin-divers were picked off, one by one, by a terrifying sea monster lurking in the fog. This is one of my favourite sea monster accounts. The problem? No-one has ever been able to determine that it ever really happened. It seems to be one of those stories that appeared in an unreferenced book (written by the likes of John Keel or Ivan Sanderson) and was then simply copied forevermore by authors implying that the initial report should be trusted. The story was retold, in illustrations, by Randall & Keane (1978).

Caption: the best sea monster story, here retold by Randall & Keane (1978). Image: Randall & Keane (1978).

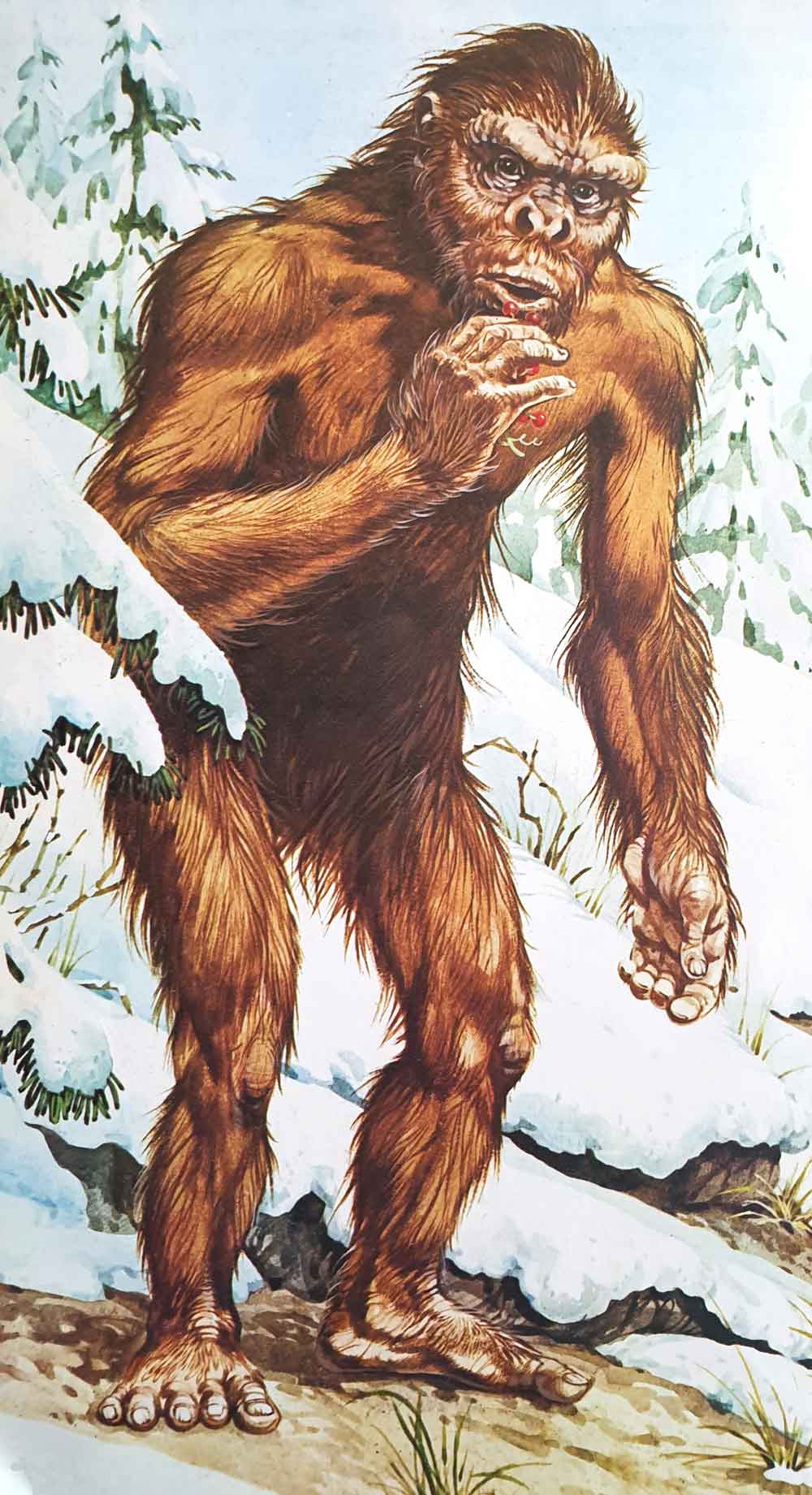

Yetis and sasquatches get a few pages. The idea that bigfoot might eat leaves, fish, rodents and stolen doughnuts and chocolate, and a montage that compares its foot anatomy with that of other primates (and bears), all serve to make this creature biologically plausible to the young mind. If you know the crypto-hominid literature, the references to such things as chocolate-eating derive from the writings of John Green, Ivan Sanderson and others.

Caption: the yeti - here, very much the Dinanthropoides of Heuvelmans - as a hominid of the snows. Image: John Francis/Usborne/Miller 1977.

The illustration of a sasquatch – I think by John Francis – always made the animal look too rangy and thin-furred for my liking (I much prefer my sasquatches to look super-buff and of lustrous pelt), but then there are at least some descriptions that do talk of creatures of this form.

Caption: a gracile, thin-furred, ‘old man’ bigfoot (which is a bit odd, given that the creature is depicted in a snowy landscape). Image: John Francis/Usborne/Miller 1977.

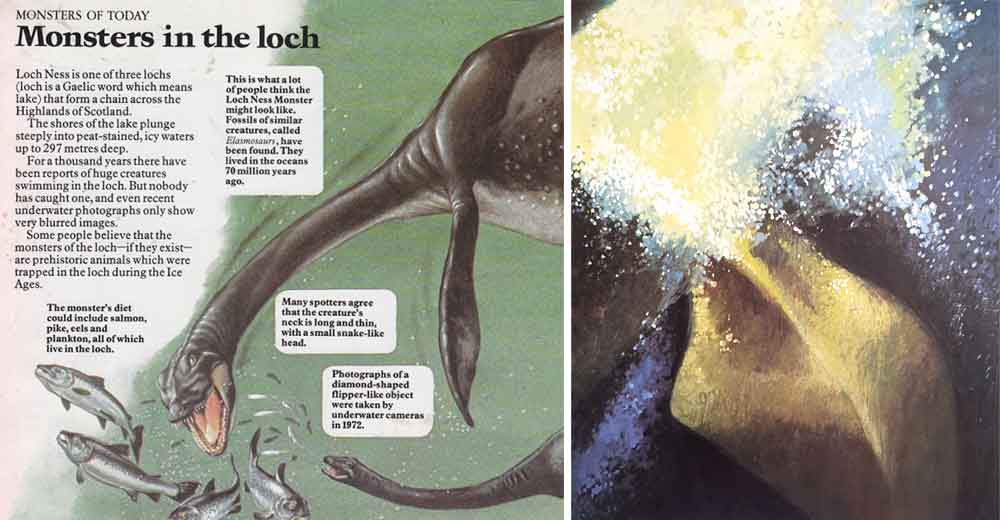

Nessie is unashamedly depicted as an elasmosaur (disclaimer: “This is what a lot of people think the Loch Ness Monster might look like”, p. 24), though the green shade of water in the background is misleading. Loch Ness is black. An artistic depiction of the famous 1972 ‘flipper photo’ is also shown, and it looks great – again, biologically plausible if you’re a young reader (and a reader who doesn’t yet know that the original photo features marks made by a paintbrush. It is emphatically not a photo of an animal’s appendage).

Caption: Nessie as a plesiosaur. And, at right, the famous flipper depicted as if it might be real. Hey, it was the 1970s. Image: Usborne/Miller 1977.

The book finishes with a section on monsters from movies. I never much liked this section because monsters made by people are obviously just not the same as monsters that might exist for real (insert ironic comment about monsters being products of culture and tradition). There’s also a glossary – a brief ‘dictionary of monsters’ – that features some more great artwork. A very attractive blue, white and red griffin, and a classic ‘wolfman’ werewolf feature, among others.

Caption: at left: a rendition of John Lambton’s battling of the Lambton worm, an oft-recounted piece of English folklore. Right: a wolfman of the Lon Chaney sort. Image: Usborne/Miller 1977.

And that’s where we’ll end things. If there’s one criticism of the book, it’s that it never really emphasises the fact that monsters – whether they be krakens, European lake monsters, yeti-type creatures or whatever – really need to be interpreted within the context of anthropology, sociology and folklore, and not interpreted from the off as descriptions of real but unknown animals.

Caption: Tyrannosaurus as a monster, dripping with blood… which, to be fair, must have happened at times. And yay ducks. Image: John Francis/Usborne/Miller 1977.

I should also note that Beverly Halstead was consultant for this book, which partly explains a few unusual details in the prehistoric animals section. Tyrannosaurus, for example, is said to have “waddled along”, a pet Halstead idea, repeated elsewhere (e.g., Halstead 1975), that was always woefully wrong. Also of note here – given this recent TetZoo article – is the old photo of the Crystal Palace Iguanodon, surely depicting the model’s appearance during the latter years of the 1970s.

Caption: the Crystal Palace reclining Iguanodon, as it looked during the late 70s. Contrast this with the images shown in the TetZoo article here. Image: Usborne/Miller 1977.

All in all, a fantastically fun book, with illustrations that remain interesting and inspirational to me today. All About Monsters very likely did inspire and foster my interest in monsters, and probably made me want to find out more about them. Did it make be believe in them, or believe in them more? I’m not sure about that. I do, however, think that it did little to hone or improve my nascent skills in scepticism or critical thinking, since one thing that appears wholly lacking from the book is the idea that monster stories should be viewed as social or cultural phenomena more than as descriptions of encounters with real creatures. Indeed, the fact that the various accounts and stories – those of Albert Ostman, Dr Pronin of Leningrad University, Mr and Mrs John MacKay of the Loch Ness region and so on – are stated as facts is somewhat problematic for a book designed to serve an educational role. That said, I retain a great fondness for what remains one of my favourite books.

Caption:Caption: water monster from the opening pages of the book. The weed snagged on the teeth is a nice touch (and reminds me of the creatures from the 1975 movie The Land That Time Forgot). Image: John Francis/Usborne/Miller 1977.

For previous TetZoo articles on cryptozoology (concentrating on articles that haven’t been stripped of their images, thanks ScienceBlogs and SciAm)…

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Bigfoot’s Genitals: What Do We Know?, August 2018

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Refs - -

Halstead, L. B. 1975. The Evolution and Ecology of the Dinosaurs. Eurobook Ltd, London.

Miller, C. 1977. All About Monsters, Usborne, London.

Randall, N. & Keane, G. 1978. Focus on Fact. No. 5 Unsolved Mysteries. W. H. Allen & Co, London.

Roesch, B. S. 1997. A review of alleged sea serpent carcasses worldwide (part one – 1648-1880). The Cryptozoology Review 2 (2), 6-27.