Among the most famous sea monster cases of all time is that of the Gloucester Sea Serpent of New England, USA…

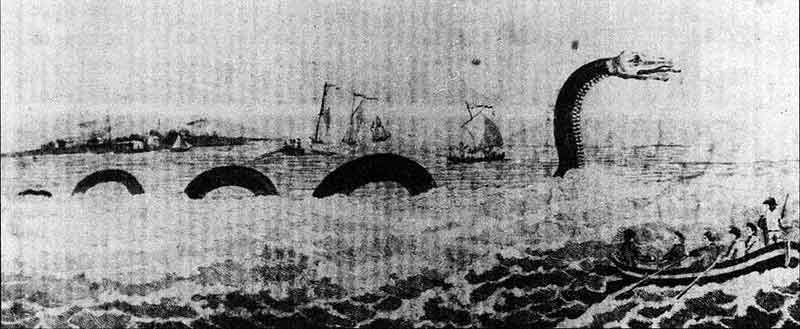

Caption: the most famous depiction of the Gloucester Sea Serpent is this fanciful one dating to August 1817, said to have been drawn from life. I don’t think the name of the artist is on record. Image: public domain.

This giant, serpentine creature was seen on numerous occasions between 1817 and 1824, often at relatively close range by large numbers of people, and often by people of respectable standing. Many drawings of the creatures were produced, but physical evidence of its existence was never obtained, the one relevant incident being the 1817 recovery of a small snake with a peculiar lumpy dorsal outline. This was very obviously a Black or Eastern racer Coluber constrictor afflicted with a spinal deformity.

The case of the Gloucester Sea Serpent is familiar enough that it’s covered in most works that review sea monsters and their claimed existence (e.g., Heuvelmans 1968), and indeed a few books are dedicated entirely to the creature itself (O’Neill 1999 [republished by Paraview in 2003], Soini 2010). How has the monster been identified? The opinion promoted most frequently by writers specialising in cryptozoology has been that it was a scientifically unrecognised, serpentine mammal with a series of dorsal humps arranged along its length (Heuvelmans 1968, Woodley 2008) or perhaps a giant sea reptile of the sort otherwise known only from the fossil record (O’Neill 1999).

Caption: two books dedicated to the Gloucester Sea Serpent – written for adults – are in existence, and both are worth reading. June O’Neill’s book of 1999 (though this is the cover of the 2003 Paraview edition), and Wayne Soini’s of 2010.

Robert France’s Disentangled is yet another volume dedicated to the Gloucester Sea Serpent, but it’s unlike any other. For all the popular and sensationalist interest in sea monsters, academic treatments of the subject are rare, making this book a significant addition to the literature; more so given that it was written by a qualified scientist with a substantial number of technical, peer-reviewed publications to his name. At this point I must spoil the surprise and reveal France’s primary hypothesis: that the appearance and occurrence of the Gloucester Sea Serpent was intimately tied to the economic and social history of the New England coast, and that sightings of this creature were actually of large vertebrate animals entangled in fishing gear (France 2019).

Caption: this is another especially famous depiction of the Gloucester Sea Serpent from 1817, and again it’s by an anonymous artist. The idea that the monster was seen at relatively close range is again emphasised. Image: public domain.

France on cryptozoology and cryptozoologists. What does France (2019) make of those authors who have gone before him, most of whom have been rather kind to the possible existence of sea monsters as valid zoological entities (that is, as giant marine animal species awaiting scientific recognition)? He is overwhelmingly critical of such writers, I think rightly dismissing their efforts as unscientific or, at least, as ‘bad science’. LeBlond and Bousfield’s infamous work on ‘Cadborosaurus’ (much written about here at TetZoo; see the links below) is not viewed favourably, nor is Michael Woodley’s 2008 book In the Wake of Bernard Heuvelmans (Woodley 2008). Michael (who no longer publishes cryptozoological articles; he and I co-authored some works between 2008 and 2012) has indeed promoted some unusual ideas that cannot be correct, these including that the ‘super otter’ and ‘many-humped’ sea monsters of Heuvelmans (1968) might actually be literal super-sized otters. France (2019) sees red, and describes Woodley’s writings here as “one of the most blatant displays of cryptozoological fancy” and a “ridiculous bit of science fiction” (p. 169).

Caption: books that discuss sea monster reports – here are some (albeit not all) of them – mostly interpret the relevant encounters as descriptions of giant, scientifically unrecognised animal species. Image: Darren Naish.

Henry Bauer has argued that sea monsters and lake monsters are based on reliable evidence supported by trustworthy experts, and that critics of cryptozoology are misguided and unscientific (e.g., Bauer 1982, 2002). But watch his public speaking and read enough of his articles and you’ll find that he endorses research denying a link between HIV and AIDS, and regards homosexuality as an illness. France has noticed this too and regards Bauer as a “fringe scientist” (p. 16).

As for the ‘Father of Cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans, France is highly critical, accusing him of sloppy scholarship, selective bias, manipulation of facts, an inability to identify hoaxes and misinterpretations of natural phenomena, of being “delusional at best, or outright dishonest at worst”, and of compiling “a house of cards assembled from a Trumpian world of ‘alternative facts’” (p. 30). Meurger (1988) is cited here as providing inspiration (it should really be cited as Meurger & Gagnon (1988)) but this takedown of Heuvelmans much more recalls Ulrich Magin’s critique (Magin 1996), paraphrased in Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017). I’ve even specifically likened the cryptozoological literalism of Heuvelmans and his followers to a house of cards, but I don’t doubt that this use of allegory could be coincidental. Cryptozoological classification schemes – the meat-and-potatoes of works by Heuvelmans, Coleman and Huyghe, Woodley and others – are described as a ‘nomenclature of nonsense’ by France (2019, p. 165).

Caption: the most influential sea monster book of them all is Heuvelmans (1968). Therein, he argued for the existence of nine distinct sea monster types, illustrated at left by Cameron McCormick. Their purported existence hasn’t exactly been embraced by biologists at large. Images: Cameron McCormick, Heuvelmans (1968).

When it comes to those who’ve been critical of cryptozoological literalism, France is quite the fan. Konar (2009) – an article I cannot claim to know – is cited and discussed since its author argues that cryptozoology is a pseudoscience. France writes favourably of Michel Meurger’s argument – promoted most famously in Meurger & Gagnon (1988) – that efforts to interpret the creatures of myth, folklore and anecdote as valid undiscovered animal species miss the point (“aquatic cryptids are ‘real’ only in the sense that they are mental constructs that have their origin in folklore and exist within a mythological landscape”; France 2019, p. 33), and he likes Daniel Loxton and Don Prothero’s Abominable Science (Loxton & Prothero 2015) and cites it frequently.

My own writings on sea monsters and cryptozoology in general are abundantly cited and fairly credited but mostly in a single paragraph on page 32 rather than scattered throughout the text as might seem appropriate. This (perhaps falsely) creates the impression that France only discovered my writings late in his project and opted to crowbar them in somewhere, but no matter.

After all this, what does France make of cryptozoology overall? Does it have value, has it been mis-framed, or is it just a pile of shit? I found France’s take on this issue difficult to parse and inconsistent. Despite strong agreement with those who argue that the study of cryptids is more to do with a sociocultural interpretation of the world, France argues in part of the book that it should be regarded as “an anachronistic form of natural history” (p. 35). He takes time to dismiss the notion that cryptozoology might be considered part of ecology. Which is odd, because surely the identification of entities reported via anecdote and observation is very obviously not ecology (assuming that ‘ecology’ relates to the study of how organisms relate to their physical surroundings) but instead more to do with systematics, biodiversity monitoring and/or social anthropology and folklore. Indeed, if the bulk of the cryptozoological literature involves the collecting of anecdotes about things implied or believed to be animals, and the evaluation of these anecdotes such that flesh and blood animals can be ‘shown’ to be at the bottom of the reports, we’re not talking about natural history or ecology but ethnozoology. France ends Chapter 1 with a hearty endorsement for the value of ethnozoology as a valid field of study, the takehome being that what people have been calling cryptozoology is ethnozoology.

The entanglement hypothesis. Introduction out of the way, France devotes the next section of the book to the 19th century ‘eco-cultural seascape’ of the North American eastern seaboard, covering the region’s geography, economy and cultural history. A classical and biblical background gave the region’s European colonists a belief system whereby elongate, unidentified marine objects (France uses the acronym UMO throughout the book) might be interpreted as gargantuan marine serpents, and some appropriate section of text is devoted to 19th century fishing methods and the technology employed. This looks on initial reading like an aside but is crucial for the argument that France (2019) later compiles, this being that entanglement explains the sea monster sightings.

But waitaminute – isn’t entanglement with marine debris (‘ghost gear’ and so on) a modern issue, linked to the use of modern fishing materials? No. It turns out that fishing gear has been lost or dumped at sea for as long as people have been making such things, that animals large and small have been becoming entangled in lost or dumped fishing gear since forever, and that seafaring people have been aware of this issue but have not had cause to report it, or have wilfully under- or unreported it, since time immemorial. Entanglement is a pretty horrible thing. Individual animals can remain bound in or connected to debris for literally years, and both old and modern materials used in fishing are made of materials that persist for decades and, potentially, centuries. As France (2019) shows via his analysis of Gloucester Sea Serpent reports, people’s descriptions of the UMOs concerned pertain to animals entangled in ropes, or swimming while connected to floats, buoys, barrels, kegs or netting. I found his case compelling.

Caption: some, perhaps many, of the sea monsters endorsed at times by cryptozoologists now need to be reinterpreted as observations of known animal species entangled with marine debris. Among them is the supposedly tadpole-like ‘yellow belly’ of Heuvelmans (1968). This imagined creature has been discussed at TetZoo on several occasions over the years. Images: Heuvelmans (1968), Darren Naish, Tim Morris.

By now it will be obvious why the book has the title that it does. Disentangled refers not only to the fact that entanglement with fishing gear explains many, most or all of the sea monster accounts relevant to the Gloucester case, but also that France (2019) has succeeded in disentangling the strands of a story that hasn’t previously been understood. Is this definitely so, though?

In view of the drubbing that cryptozoological literalists receive throughout France’s book, it’s ironic that Heuvelmans (1968) was the first to propose the entanglement hypothesis. In attempting to interpret a sea monster seen in Cape Town Harbour in 1857, and reported by a Dr François Biccard and seven other observers, Heuvelmans (1968) wrote that “This so-called body is so unlike any part of an animal that one cannot help thinking that it may have been a net or rope towed by a shark or [France has ‘of’ here] porpoise which had got caught in it and whose wounded body appeared to be what the doctor called the head” (Heuvelmans 1968, p. 242). But, alas, poor Bernard, here “Demonstrating a degree of perceptive reasoning markedly absent from the rest of his tome…” (France 2019, p. 194). Damned with faint praise. Incidentally, France (2018) has written a whole paper on the Cape Town Harbour case and its significance.

Caption: Biccard’s illustration of the 1857 sea monster (or UMO) seen from Table Bay, Cape Town. There weren’t two monsters: the picture shows two views of the same object. Heuvelmans (1968) was unable to place this creature within any one of his nine sea monster categories. Image: public domain.

But if the Gloucester Sea Serpent (and at least some other sea monsters too) really was an animal entangled in lost or discarded fishing gear, what specific animal are we talking about? France (2019) eliminates whales for various reasons and favours the view – in part based on the swimming speed of the monster, its ability to make extremely tight turns and its propensity to frequent very shallow water – that the most likely candidate was the Bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus. “Most likely”? Is that the best we can do? The fact that the monster’s true identity can’t be precisely determined and remains unresolved is slightly awkward given France’s (2019) determination earlier in the book that cryptozoology is unsatisfyingly unspecific, and France readily admits this. But as a committed advocate of the notion that providing a provisional or ad hoc scientific conclusion is by no means problematic, I don’t see an issue.

Caption: tuna are remarkable fishes, and France (2019) emphasises how incredible they are. Strong, fast, and surprisingly big (this life-sized model – formerly on show at London’s NHM – is about 2 m long), they might help explain the Gloucester Sea Serpent UMO. Image: Darren Naish.

Yes, I agree with Robert France that entangled marine vertebrates are the real explanation behind some, if not many, sea monster sightings… or UMOs, if you prefer… and specifically those associated with Gloucester Harbour, Massachusetts. I’m slightly embarrassed not to have noticed this earlier. But, then, to reach this conclusion and write authoritatively about it requires not only a familiarity with the sea monster literature and cryptozoological lore but also with the anthropology, economy and industry of North America’s eastern seaboard, and few of us have been focused enough, or expert enough, to do that. Professor France, I raise my glass.

Caption: the entanglement hypothesis doesn’t mean that all ‘sea monster’ reports describe animals that can be interpreted in the same way: some accounts are, more likely, just misidentifications. One example mentioned by France is that of the ‘baby Cadborosaurus’, reinterpreted by myself and colleagues in 2011 (Woodley et al. 2011). Image: Woodley et al. (2011).

A few statements and proposals made in the book are objectionable and might be deemed wrong by a reader with specialised knowledge. The idea that the Spicer land sighting of the Loch Ness Monster was inspired by a scene in King Kong (mentioned favourably by France on p. 32) has experienced something of a pushback recently and should not be mentioned as if we know that it actually happened. France also refers to the kraken as if it’s the same thing as Architeuthis, the giant squid. This notion, while still popular, is not consistent with evidence (Paxton 2004, Naish 2017). Tim Dinsdale’s famous Loch Ness film of 1960 is not “waves plus a little imagination”, as France states (p. 181), but a boat. It is also wrong to state that lake monsters (like the Loch Ness Monster) are “known to [be] misidentified natural phenomena” (p. 173) and to cite ‘Binns 2017’ as if this is what Binns (2017) is all about: sure, misidentified natural phenomena have contributed to belief in lake monsters, but they don’t provide ‘the’ explanation given that there are lake monster sightings that involve known animal species, boats and so on. Binns (2017), incidentally, was reviewed here at TetZoo.

A curious aside concerns a case irrelevant to France’s entanglement hypothesis, this being Captain Hanna’s mystery fish of 1880. Hanna’s fish has variously been considered a mysterious long-bodied chondrichthyan (Heuvelmans 1968), a possible new species of long-bodied teleost (Roesch 1997; though note that a modern Ben Speers-Roesch does not support this idea) or an oarfish. France (2019) considers the last of these suggestions correct, the fish being “clearly recognizable” as a member of this species (p. 241). In the same section of text, France also notes that Frilled sharks Chlamydoselachus anguineus are sufficiently monster-like that a sighting of a live one near the sea surface “would be all that it would take to raise the cry of ‘sea serpent!’” (p. 242). More exciting is that France (2019) takes seriously the suggestion (made in an online 2015 National Geographic article) that “an 8 metre-long related animal was caught in 1880” (p. 242), the implication being that giant frilled sharks might be out there and awaiting discovery. That’s not altogether ridiculous given the recent discovery that Goblin sharks Mitsukurina owstoni – long assumed to not exceed 1.5 metres in total length – have been shown to sometimes exceed 6 metres in total length (Parsons et al. 2002). But there’s some confusion here: the 1880 ‘related animal’ is one and the same as Captain Hanna’s mystery fish!

Caption: S. W. Hanna’s sketch of the giant mystery fish – 7.6 m long – captured in a net off New Harbor, Maine, in 1880. Most books on sea monsters mention or discuss this animal, most frequently with the (frankly very silly) idea that it might have been a giant serpentine shark. Image: public domain.

My biggest gripe concerns the book’s editing. Alas, this otherwise fine and well-designed book does not appear to have been thoroughly proofed, for conspicuous and often amusing typos abound. Among those I spotted are ‘Huevelmans’ (p. 30, for Heuvelmans), ‘by his by living’ (p. 34, for ‘by his living’), ‘gapping mouth’ (p. 63, for ‘gaping mouth’), ‘sheds her objectively’ (p. 90, for ‘sheds her objectivity’), ‘as to creature’s identity’ (p. 92, missing ‘the’), ‘crypotozoologists’ (p. 141), ‘flour legs’ (p. 161, for ‘four legs’!), ‘pinnepeds’ (p. 169, for ‘pinnipeds’), ‘in in 1809’ (p. 184), ‘Prionace glavca’ (p. 227, it should be P. glauca), ‘more than a three hundred m’ (p. 227), ‘odentocetes’ (p. 228, for ‘odontocetes’), ‘merebeing’ (p. 265, for ‘merbeing’), and ‘preciously here’ (p. 246, for ‘precisely here’). I have to add that the lack of an index is a major and surprising weakness.

Oh, one final complaint, and it’s one that, regretfully, I so often voice in my book reviews: this book is phenomenally expensive. It’s £50 in the UK, €68 in continental Europe, and $77 in the USA. As per usual, the argument here – I suppose – is that it’s meant for institutions and their libraries, and not for individual researchers. Huh.

Caption: France (2019), one of the most important volumes now published on sea monsters, and certainly the most technical. Image: Darren Naish.

These issues aside, Disentangled, then, is a thoroughly worthy and interesting book, and those seriously interested in sea monsters, anthropological use of the sea, marine folklore and marine ecology and pollution should read it. The book itself is dense, with small print and copious black and white illustrations, and I like its design. With the publication of this book, we have entered a new era in our understanding of sea monsters and every subsequent work on the subject will have to cite and mention it. And it is a sad indictment on our species, on our impact on the planet and its other animal species, that the solution to what was long deemed one of nature’s greatest mysteries is resolved as but a deleterious consequence of our unthinking, wasteful and harmful ways.

France, R. L. 2019. Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, The Netherlands. pp. 289. ISBN 978-90-8686-335-8. Softback. Refs. Here at publishers. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

For previous TetZoo articles on sea monsters (and lake monsters too), see… (reminder: articles at ver 2 and 3 are mostly ruined by hosting issues)…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

A baby sea-serpent no more: reinterpreting Hagelund’s juvenile Cadborosaurus, September 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

The Cadborosaurus Wars, April 2012 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

Refs - -

Bauer, H. H. 1982. The Loch Ness monster: public perception and the evidence. Cryptozoology 1, 40-45.

Bauer, H. H. 2002. The case for the Loch Ness “monster”: the scientific evidence. Journal of Scientific Exploration 16, 225-246.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press.

France, R. L. 2018. Illustration of an 1857 “sea-serpent” sighting re-interpreted as an early depiction of cetacean entanglement in maritime debris. Archives of Natural History 45, 111-117.

Heuvelmans, B. 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Konar, G. 2009. Not your everyday animals: applying Occam’s Razor to cryptozoology. The Scienta Review, MIT.

Loxton, D. & Prothero, D. R. 2013. Abominable Science! Columbia University Press, New York.

Magin, U. 1996. St George without a dragon: Bernard Heuvelmans and the sea serpent. In Moore, S. (ed) Fortean Studies Volume 3. John Brown Publishing (London), pp. 223-234.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters. Arcturus, London.

Parsons, G., Ingram, G. W. & Havard, R. 2002. First record of the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni, Jordan (Family Mitsukurinidae) in the Gulf of Mexico. Southeastern Naturalist 1 (2) 189-192.

Paxton, C. G. M. 2004. Giant squids are red herrings: why Architeuthis is an unlikely source of sea monster sightings. The Cryptozoology Review 4 (2), 10-16.

Roesch, B. S. 1997. A review of alleged sea serpent carcasses worldwide (part one – 1648-1880). The Cryptozoology Review 2 (2), 6-27.

Soini, W. 2010. Gloucester’s Sea Serpent. The History Press, Salem, Massachusetts.

Woodley, M. A. 2008. In the Wake of Bernard Heuvelmans. CFZ Press, Bideford.