There can’t be many visitors here who are unaware of Dougal Dixon and his 1981 book After Man (Dixon 1981), the work which effectively started the entire Speculative Zoology (or SpecZoo) movement.

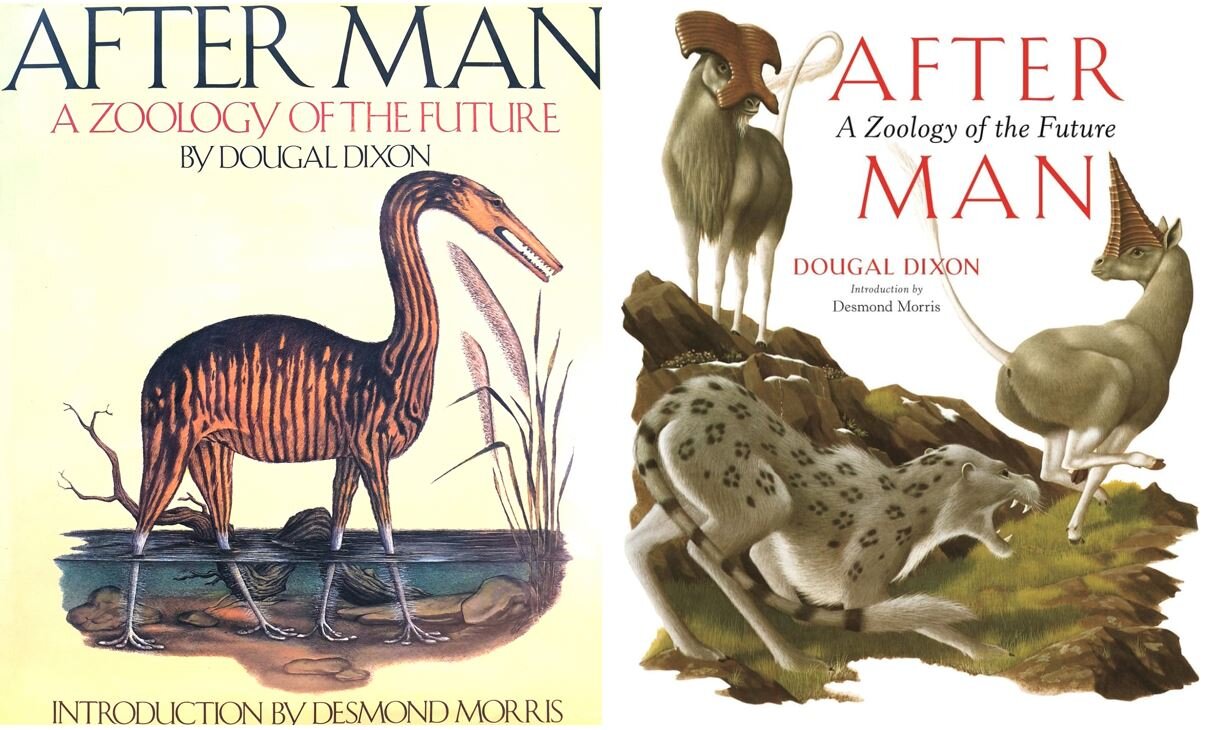

Caption: the 1981 (Grenada) and 2018 (Breakdown Press) editions of After Man.

Dougal’s writings have been discussed at TetZoo on quite a few previous occasions (see the links below); among the more significant of these are the 2014 interview piece, and my review of the 2018 on-stage event at Conway Hall in London, timed to coincide with After Man’s republication in that year (Dixon 2018). This latter article discussed the presence at that Conway Hall event of a number of exclusives which Dougal was kind enough to bring along, and among the most interesting of these was…. the original After Man pitch document! This reveals his initial vision for the book, lists and mentions all the material planned to feature in the book, and features a great many concept illustrations which have never been seen elsewhere before.

Today, I have a very special surprise. Dougal has very kindly loaned me said aforementioned pitch document, and – in the article you’re reading here – you’re going to see its contents. This is a world exclusive. I have full permission from Dougal to share the images and information. The material concerned is © Dougal Dixon and cannot be reproduced without permission.

Caption: for the 2018 launch of the Breakdown Press edition of After Man, Dougal brought the initial pitch document, various models he’d made of the animals (like the Vortex shown here), and translated editions of the book. It was a privilege to see these many things. Images: Darren Naish.

First off, a brief bit of background. As Dougal explained in the interview we carried out in 2014, After Man was the culmination of a decades-long thought experiment which – remarkably – Dougal had developed since childhood. By the time he was working in publishing, Dougal felt that a volume on the hypothetical animals of the far future might be successful. And he was sufficiently experienced in book production to know how to prepare a compelling pitch document. He prepared one (effectively, it’s a breakdown of the book’s contents, explaining what it would look like and how it would read), took it to two publishing houses (one of which was Granada, based in London) and… got a successful book deal immediately (both companies wanted to publish it; I’m guessing Grenada offered the better deal). The rest is history: After Man remains a classic work, has been translated into numerous languages, and has an enormous global fanbase, nearly 40 years after its publication.

Caption: at left, an iconic photo of Dougal (originally featured on the After Man dustjacket) with his model Night Stalker (the giant flightless bat of the Dixonian Era). At right: there’s a lot of After Man fan art out there now; this image features several of After Man’s mammals. Images: Duncan McNicol/Dougal Dixon; Darren Naish and Rebecca Groom.

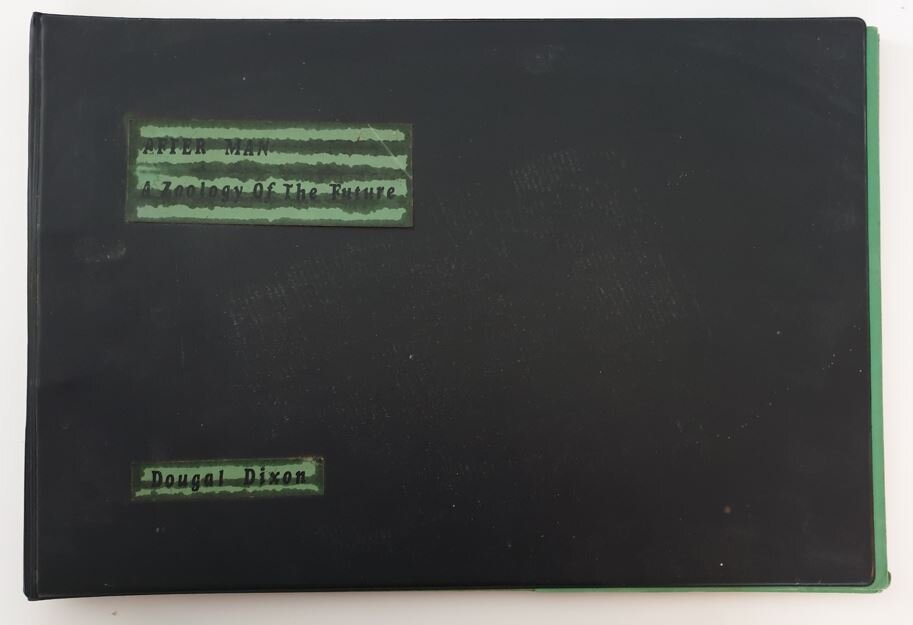

The pitch document is housed within a large, dark ring-binder. Type-set pages (I think produced on a word processor) explain how the book will be broken down, the style the author will use (“The book is written in the present tense – as though the things described are observable today”), and the market sector the book will appeal to. The breakdown is amazingly detailed, and it’s obvious that Dougal’s extensive experience with publishing and book preparation meant that he knew exactly what to do in convincing the publishers that this was a fully fleshed-out vision.

Caption: the sacred text.

There’s even reference to the fact that the book would include an introduction by a celebrity (Desmond Morris would take that role). This would be published alongside an illustration which showed “one of the more spectacular animals drinking from a stream, oblivious to the fossil in the opposite bank of a human skeleton or a recognizable artefact”. Such an illustration does not appear in the final version, which is sad as it sounds great. I can imagine that someone in publishing might not have wanted the book to lean too heavily on the fact that the book is set in a world where all of humanity is dead, since that might be depressing.

The pitch document’s text again emphasises that Dougal knew exactly what he was doing: it outlines the contents for literally every page of the book and includes sample sections. I compared this list of contents with the final product. While some things got shifted around, what’s in the pitch document is essentially still accurate. Of interest (to me, anyway) is that the animals didn’t yet have their final names – or, rather, these names aren’t used in the pitch document – so they’re referred to as, for example, “ungulate rabbit” (rather than rabbuck), “woolly mammoth antelope” and “woolly titanungulate” (rather than Woolly gigantelope) and “ibex-like rabbit” (rather than Mountain rabbuck); there’s also reference to “mammalian skinks” (the prototype version of the Desert shark, I suppose). I’m intrigued to see from the pitch document that the predator rats are repeatedly compared not merely to canids in general, but specifically to Borzoi in appearance.

Caption: I hadn’t previously known that Borzoi (part of the sighthound group; essentially long-haired greyhounds) were referenced in the design of After Man’s predator rats. Dougal’s concept sketches of predator rats are shown at right. Images: 1911 painting by Maud Earl, from The New Book of the Dog (original here); (c) Dougal Dixon.

Are there any sections in the pitch document which describe things that didn’t make it into the book? It seems that the section on mountains was going to be a few pages longer and include discussions on Mountain rabbuck and “A descendant of the yeti”! The deserts section includes reference to “a communal beetle that forms a sort of testudo when things get really tough”, and there’s also a planned “far future” section which would have discussed things beyond the Dixonian Era, like the death of the Solar System.

Caption: the BOOK PLAN for After Man. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

What about the graphic side of this document? Two large gatefold sheets of green card are covered in small, full-colour mock-ups of the book’s page layout, or plan. As you can see, the format Dougal initially had in mind differs somewhat from the final product, mostly in that the illustrations and text are more inter-mingled and the main feature illustrations were not planned to occupy stand-alone plates as they eventually did.

My favourite feature of the plan is the double-page introductions to each section where we see a diorama of the habitat in question, filled with its respective Dixonian animals. There are illustrations depicting the different habitats in the final book, but they’re one-page vignettes and don’t feature the animals. I wish they’d been produced, they would have been awesome. Why weren’t such scenes produced? I wonder if it’s because they would have created unrealistically crowded scenes which might have ruined the natural history vibe the book was going for (though, it has to be said that there’s a long tradition of natural history volumes including unrealistically packed scenes of this nature).

Caption: one of the planned section opener spreads from the the pitch document. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon.

A large draft for just ONE of these double-page introductory scenes was produced for the pitch document, the one for Tropical Grasslands. As you can see, it features several animals which appeared in the final version of the book (including gigantelopes, rabbucks, predatory baboons and the large scavenging mongoose called the Ghole), but there’s also a bunch of stuff that didn’t, including birds and squamates of several sorts. The termite mounds are shaped the way they are because the relevant termite species have a symbiotic relationship with mammalian scavengers, and utilise the bone scraps which the mammals leave behind. You’ll notice, incidentally, that the text is ‘dummy text’, included where it is for reasons of planning and design (most often, such text is Lorem Ipsum, a section of filler lifted from a 16th century Latin work which quotes the words of Cicero).

Caption: initial spreads for the tropical forests section. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Two other draft versions of what the book’s spreads might look like were also produced. One (focusing on tropical tree-dwellers) includes behavioural vignettes which depict the Striger (a hyper-gracile cat), Clatta (a primate with a prehensile, armour-plated tail), Flunkey (a marmoset-like monkey equipped with gliding membranes), Ziddah (a gracile African monkey convergent on spider monkeys) and Khiffah (a group-living monkey with strong sexual dimorphism).

Caption: at left, the hyper-gracile arboreal cat of the pitch document, engaging in some quality primate control. And - at right - its presumed descendant of the published work, the Striger. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Incidentally, I much prefer the version of the Striger featured in the pitch document – it looks so much more believable than the brachiating monkey-cat which features in the book. I love the style of these illustrations – I might even prefer them to some of the final published images – and they affirm Dougal’s talent as an artist.

Caption: a mock spread from the pitch document showing marine animals, most notably the Vortex. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Finally, we have a draft spread which features an early version of the Vortex (together with a diagram depicting its convergence with whales and Mesozoic marine reptiles). Dougal’s drawing of the Vortex – a rorqual-sized, planktivorous penguin – makes me wonder if there was a miscommunication in its design at some point. Dougal’s illustration makes it look as if the Vortex’s filtering apparatus is formed of numerous interlocking, spicule-like denticles that grow from the upper and lower jaws. Yet the animal in the book – gloriously depicted by Diz Wallis – doesn’t have anything like this; it instead has vertical grooves on the sides of a massively deep upper jaw which (like that of a right whale) seems to contain long, baleen-like filtering plates. Did Dougal change his mind about the way this animal is meant to do its filtering? Or was a mistake made? I must ask at some point.

The spread also features some odd-looking aquatic beasts which didn’t make it into the final book, namely a few flexible, long-necked descendants of otters and a sirenian-like giant beaver.

Caption: the original pitch version of the Vortex compared with the final version, a rather different Kaiju penguin (at least in bill anatomy). Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

And that’s about it! I have one final thing to discuss, which is that Dougal has also passed me a file containing his original sketches and portraits of the book’s many animals. Given that I’ve been lent an entire folder of these drawings, I’m not about to share them all, so here are a few of those I find especially interesting. Not only do they again demonstrate Dougal’s skill as an artist, they sometimes reveal a little more of the original character and design of the creatures, and also depict scenes, poses and pieces of behaviour that didn’t make it into the book.

Caption: original concept sketch showing Dixonian animals of a coniferous forest. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Among the latter are a scene showing the volcanic nesting grounds of the Skern (a big, flightless, wingless, foot-propelled seabird), an illustration of a Desert spickle (a spiky-backed, nectarivorous rodent) climbing among cactus spines, and a planned coniferous forest scene which looks like the prototype of one of those diorama scenes I mentioned earlier. I also like Dougal’s drawing which shows the Angler heron with one of its manufactured pools, a reduced version of which appeared in the book. I also need to add that the file includes what appears to be the very first pencil concept sketch of the Night stalker!

Caption: at left, Dougal’s concept sketches of what happens after a Gigantelope is killed by a Horrane, and then scavenged by raboons and Gholes. Versions of these illustrations appeared in the book, but not the one at the top. At right: what appear to be the very first prototype illustrations of the Night Stalker, one of the most popular and spectacular Dixonian creatures. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

I will finish by repeating a point I’ve made a few times before (including in the 2014 interview)… something should be done with all of this material. By which I mean: it should see print at some point. Dougal has a sufficient fanbase that such a project would surely be commercially viable, and I’m sure those of us who love After Man would much appreciate seeing its backstory told in published form. I’d love to take the reins on this myself, but I’m already drowning in unfinished, in-progress projects of my own and mustn’t take on anything else.

Caption: another reminder that Dougal’s After Man project included so much extra material beyond that included in the book. There’s a substantial amount of additional art, and models and puppets too. These illustrations depict Megalodorcas giganticus, the Gigantelope. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

I hope you enjoyed this exclusive behind-the-scenes look, and I’m sure you’ll join me in thanking Dougal for allowing me to use it. We will end there, but I assure you that we’ll no doubt be visiting SpecZoo again in the very near future.

For previous TetZoo articles on Dougal Dixon’s works and connected aspects of SpecZoo, see…

Oh no, not another giant predatory flightless bat from the future, March 2007

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Giant flightless bats from the future, November 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

The LonCon3 Speculative Biology event, August 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, July 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1981. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Granada, London.

Dixon, D. 2018. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Breakdown Press, London.