As remarkable as it might sound, we’re presently in the midst of a ‘modern werewolf’ craze…

Caption: werewolves in modern day America. From left to right: Linda Godfrey illustration of a creature seen kneeling at the roadside in Elkhorn, Wisconsin, as reportedly seen by Lori Endrizzi in 1989; the 1936 ‘gadarrah’ creature described by Mark Schackelman from near Jefferson, Wisconsin; and Tina Cole’s sketch of a creature she recalls seeing in Michigan in 2001, when she was eight years old.

I don’t mean with respect to erotic fanfiction or fursona representation at conventions, but to claimed real-life encounters with living, breathing, dog-headed humanoids. Such is current interest in these werewolf monsters – we’re talking about an entity most often dubbed dogman – that they’re among the most frequently discussed of all creatures within the mystery beast canon.

The dogman craze got off the ground following the early 1990s collecting of reports from the vicinity of Elkhorn, Wisconsin, and indeed Wisconsin and adjacent Michigan are the areas most associated with dogman accounts. These involve the claimed observation of creatures today known as the Beast of Bray Road or Bray Road Beast – Bray Road, Wisconsin, being the place where several of the initial reports occurred – or the Michigan dogman.

Caption: Linda Godfrey was a skilled artist who illustrated dogman / the Beast of Bray Road several times. One of her illustrations – it featured in her 2003 book The Beast of Bray Road – is shown here; the photo of Linda shown here appeared in several interview articles on her.

One person above all others got dogman widely known and catalogued in the literature, and that’s Wisconsin-based journalist, author and researcher Linda Godfrey. Godfrey died of Parkinson’s Disease in 2022, aged 71, and probably all of the many obituaries devoted to her note her influence in bringing the Beast of Bray Road to wide attention. She was very much the ‘go to’ person on the subject after uncovering the creature’s alleged existence in 1991.

Caption: the small town of Elkhorn, Wisconsin, is about 100 km to the west of Lake Michigan, about the same distance to the south-west of Milwaukee, and about 80 km to the north-west of Chicago. It’s in the extreme south of Wisconsin and was home to around 10,000 people in a 2010 census. Image: Google maps.

Caption: Bray Road – marked with an arrow – as it looks from the air. The rural, agricultural nature of the surrounds is obvious. The entire location is fairly open farmland with some tree cover. Image: Google maps.

The sightings. As relayed in her 2003 book The Beast of Bray Road, Godfrey owed her initial awareness of these accounts to an unnamed local freelance journalist who, in turn, had heard accounts relayed by a bus driver called Pat Lester. Lester’s daughter, Lori Endrizzi, had seen “a wolf or large dog with human characteristics” in the autumn of 1989, and it turned out that a teenage neighbour – Doris Gipson – had seen it too. Endrizzi’s sighting described the animal kneeling at the roadside at 1.30 in the morning, apparently holding roadkill. Gipson’s account, dating to Halloween 1991 (yes, Halloween), involved her hitting an animal with her car, stopping to check out the damage, and then having to escape at speed from the pursuing creature… which she then saw again on the same night, and had it attack the back of her car (Godfrey 2003).

Caption: images of Bray Road as it looks in 2024. Images courtesy of Tyler Stone, used with permission.

A December 1990 account, reported by a witness who was only 10 or 11 at the time, was also regarded as part of the same sighting flap, as were additional observations from other children in the same group (Godfrey 2003, p. 12). Clawed footprints suspected to be from the creature had been mentioned to the director of the Lakeland Animal Shelter, and at least some local people apparently took to using the nickname ‘Pottsy’ for the creature, presumably after Potter’s Road where the tracks were found (Godfrey 2003, p. 12).

Also during 1990, Mike Etten was driving along Bray Road late at night when he observed an animal bigger than a wolf, “sitting like a raccoon sits” and eating something held in its forepaws. A high school student called Tom Brichta is credited with two 1992 sightings of a shaggy-coated humanoid creature, the first of which involves the creature partly colliding with his car, the second – this one making reference to the dog-like head – describing how the animal was seen standing among 6-ft-tall corn (Godfrey 2003, pp. 38-41).

Caption: it might be obvious that the people of the Bray Road area are having fun with the dogman phenomenon today; an image taken during the Summer of 2024. Image courtesy of Tyler Stone, used with permission.

Some of the accounts that Godfrey uncovered long pre-dated the 1990s, in particular one recalled from 1936 that took place close to Jefferson, Wisconsin. This came to Godfrey via author and editor Joe Schackelman, who was himself relaying what his father, Mark, told him in 1958 (Coleman 1998, Godfrey 2003, DeMello 2023). A large, human-sized animal had been observed, kneeling on and clawing at an indigenous burial mound created by the Hopewell culture (DeMello 2023). What was supposedly the same creature was seen again on a second night, this time in a more extended encounter. 6 foot tall and with visible fangs and pointed ears, it made eye contact and an utterance described as “gadarrah”… more on that below. Joe Schakelman’s drawing, based on his interpretation of his father’s description, shows an erect-bodied, tailless, dog-headed creature with extended arms and folded wrists. What were interpreted as its first and fifth fingers were curled up and “shrivelled” (Coleman 1998, Godfrey 2003, pp. 26-27). Also of interest is that the illustration shows the animal as plantigrade, meaning that it was placing the heel of its foot on the ground.

Caption: the Mark Schackelman dogman/werewolf, as illustrated by his son, Joe, decades after the sighting is said to have happened. This drawing has appeared several times in the literature (Coleman 1998, Godfrey 2003, 2012). Things to note include the plantigrade feet, the bent wrists, and interesting curled structures on the inner and outer parts of the hands. Image: Joe Schackelman, from Godfrey (2003).

Other alleged dogman encounters have been reported and recorded since Godfrey amassed this selection in the early 2000s, but these are the foundational reports that got the phenomenon off the ground. They hint at several interesting points worth commenting on. The first is that a tradition of werewolf belief, local to the Bray Road area, had arisen among people there, especially the young ones. The suspicion when such things happen is that a sort of snowball effect emerges, either because other people want in on the fun, or because the phenomenon becomes a source of local identity that others seek to reinforce.

Caption: Godfrey, as shown in the 2024 Small Town Monsters movie, holding open the issue of The Week that contains her article ‘Tracking down ‘The beast of Bray Road’’. The illustration shows the kneeling dogman, a piece of carrion in its hand, described by Lori Endrizzi. Image: (c) Small Town Monsters.

The second is that some of the accounts that Godfrey collected don’t seem at all reliable, especially those involving children and what sound like tall tales from Halloween. And I want to emphasise that last point in particular: the initial, foundational dogman accounts are all highly suspicious, mostly unrealistic, and really make it seem that this was a cultural event whereby a bunch of locals were telling tall tales and fun, scary stories. I think it at least plausible that some observations of real animals – Etten’s roadside animal that sat like a raccoon could actually have been a raccoon, for example – got mixed in with the whole thing, but… otherwise, we really should be very sceptical of the inference that there was anything ‘real’ here in the first place. Are any of the dogman sightings reported in more recent years really descriptions of encounters with real animals? I’ve assumed that some are, but we really are talking about a handful of reports here.

Indeed, an issue obvious throughout Godfrey’s writings is that she collected and published any and all stories and anecdotes describing unusual hairy animals, the result being that what might look like a substantial roster of dogman reports is diluted by a number of probably irrelevant cases. Her 2003 book The Beast of Bray Road includes reports of big, shaggy, dog or wolf-life quadrupeds (pp. 31-34, 58-59), wildman or bigfoot-type creatures (pp. 34-38), and quadrupedal canids described as recalling giant coyotes or German shepherds (pp. 51-52).

Caption: I’m not sure how relevant it is to the whole dogman/American werewolf phenomenon, but it’s worth noting that certain domestic dogs can look surprisingly odd – disturbing even – in some circumstances. I like this photo of a large pet dog (it looks to be an Irish wolfhound), since it makes the point. Imagine how a person might react to seeing an animal like that standing bipedally for a moment, glimpsed among crops or foliage. I saved this image after seeing it on Facebook and haven’t been able to find a proper source.

Indeed, obvious throughout Godfrey’s writings is that she was forever aiming to bulk up the exceedingly slim dogman dossier through reference to any and all connected things, however tenuous the link. A fair amount of her The Beast of Bray Road describes local media coverage, Godfrey’s own experiences as an interviewee and media personality, and a huge quantity of musings concerning whatever she could dig up on werewolves and lycanthropy (Godfrey 2003).

Caption: Steve Cook’s song The Legend was first released on the radio (on April Fools Day, 1987), and later sold on CD and DVD. It is a work of fiction. Local TV station WTCM held an art competition, inviting viewers to send in their depictions of what the dogman might look like. The charcoal illustration (at right) of an especially monstrous dogman – by Brian Rosinski – became regarded as the best and most chilling of these. Rosinski was 23 years old at the time and without artistic training. The image is still associated with The Legend at some locations online.

Incidentally, a song – Steve Cook’s The Legend, first played on public radio in 1987 and then available for sale on CD and, later, DVD – relates a number of real-sounding Michigan dogman encounters and thereby creates the impression that the phenomenon has a pre-Godfrey tradition. But… it’s a song; essentially a work of creative fiction. Godfrey’s interpretation of its contents after discussing it with Cook was that the tales it recounts reminded her of dogman stories she knew from Wisconsin (Godfrey 2003, p. 64), and Cook’s song did help solidify the idea that dogman might be real, and with an attested history in the region. But Cook’s song was played as an April Fools Day gag (Godfrey 2012, p. 288). It was never meant to be relaying ‘real’ history of any sort.

Caption: Godfrey’s two original books. 2003’s The Beast of Bray Road was self-published. She produced others later on, including American Monsters: A History of Monster Lore, Legends, and Sightings in America in 2014 and Monsters Among Us: An Exploration of Otherworldly Bigfoots, Wolfmen, Portals, Phantoms, and Odd Phenomena in 2016.

The Gable dogman film. Another piece of creative media was also used, for a time, to bolster the case for dogman: a supposed vintage home movie, dubbed the Gable dogman footage. It did the rounds in 2007 and was uploaded to YouTube in 2009. You can watch it yourself here. Grainy, and revealing clothing and vehicles suggestive of its being set in the 1970s, it depicts countryside scenes from rural North America – Michigan, apparently – as a Mr Aaron Gable is filmed by one of his sons. Gable junior, filming from a car window, captures a glimpse of a human-sized, dog-like quadruped standing on a rise at the side of the road. The creature bounds on all fours towards the car and briefly disappears from view before its toothy maw flashes in front of the camera just before the film ends. A second, separate segment of film shows part of the police investigation as detectives survey a scene of death and dismemberment.

Caption: stills from the Gable film. At left, the creature begins to bound towards the camera operator. At right: shock horror, the creature leaps up at the window and we see its open mouth for a second or two… then the footage ends.

Despite its name, the Gable film – even if interpreted as genuine – never should have been considered part of the same phenomenon as Linda Godfrey’s Beast of Bray Road seeing as the creature it depicts is a bounding quadruped, not a humanoid. It was shown to be a hoax in 2010, and in fact a staged ‘unveiling’ of the whole thing, performed in co-operation with the hoaxer himself – Mike Agrusam – formed the focus of the final episode (titled America’s Wolfman, broadcast in March 2010) of the History Channel TV series MonsterQuest. Agrusam used an 8mm camera to create the impression of age and had worn a ghillie suit, and bounded on all fours while wearing it, when playing the creature.

Caption: another still from the Gable film. The camera operator, a young person with what looks like a hand-operated Nikon Super Zoom 8, is glimpsed briefly in the wing mirror of the car. A nice touch!

It turned out that Steve Cook – the musician behind The Legend song – was responsible for this piece of media too and had devised the film as a consequence of flagging sales of The Legend CD. He worked together with Agrusam and edited out some comical moments that Agrusam had initially included (Godfrey 2012). Cook’s cover story was that the film, stored in old cannisters labelled ‘Gable’, had been obtained via an estate sale. He sent copies to Godfrey and other researchers (Godfrey 2012) but obviously kept them in the dark as to the film’s fraudulent nature.

Dogman right now. Today, dogman accounts are not infrequently recounted in venues devoted to bigfoot and allied phenomena, and my rough impression is that something like 50% of people who endorse the existence of bigfoot also regard dogman as a genuine phenomenon, rather than as just a piece of folklore. At this point we come to a philosophical impasse of the sort not uncommon in the world of cryptozoological claims. To people who view the universe from a critical, evidence-based perspective – and this includes the majority of naturalists, scientists and authors with even a passing interest in cryptozoology – dogman is not real, cannot be real, and all reported accounts can only be hoaxes, tall tales, old folkloric accounts that are recast to sound as if they’re set in the modern day, or mistakes.

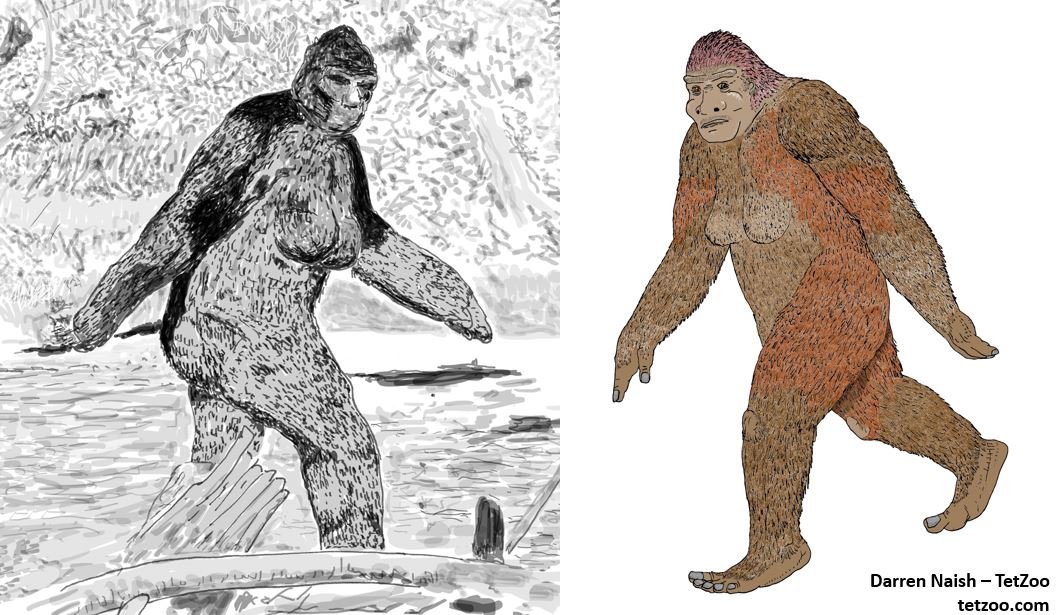

Caption: if you believe in bigfoot, chances are high that you accept the existence of dogman too. Twenty years ago, this would have been a ridiculous thing to say. These days…. well, not so much. Here are different images of ‘Patty’, the supposed bigfoot that features in the 1967 Patterson-Gimlin film. Images: Darren Naish.

But to a number of people who talk about dogman on podcasts, YouTube and the like, the implication is that we really are hearing here about a phenomenon unexplained by science, concerning either a mystery flesh-and-blood animal – a new species or some ungodly hybrid – or an entity from another realm that somehow, sometimes, manifests in our own. Here’s where we come back to Schackelman’s ‘gadarrah’ creature. Gadarrah is a word that has connections with Biblical Christianity. Also spelt Gadara, it’s the name of a region of Judea close to the Sea of Galilee, and famous as the place where Christ performed an exorcism.

Caption: the story of Jesus performing an exorcism and casting out demons that then possessed swine (that then leapt into the river and drowned) is a well known bit of Christian lore. It has been associated with places variously termed Gerasa, Gadara, or Gergesa. This 6th century AD mosaic, depicting the scene, is at the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy. Image: public domain (from here).

Godfrey (2003, 2012) and others heaped significance on this point, the idea being that this ‘links’ dogman with a spiritual view of the world, perhaps one involving black magic and the occult. Maybe – according to this view – dogman itself is ‘demonic’. In talks she gave, Godfrey emphasized the fact that Schackelman’s encounter was associated with a burial mound, the implication being that dogman has a connection with the spiritual, satanic or demonic (J. Card, pers. comm. 2024). The 2024 Small Town Monsters movie The Bray Road Beast explains that Endrizi, one of the initial dogman witnesses, regarded dogman as “satanic in origin: a demonic entity or, perhaps, the Dark Prince himself”, and suggestions that dogman might be evil have been made by others too.

To clarify my own position in case it’s not already clear… there are hoaxes and fabrications in the dogman canon, but I also think that there are misinterpreted or embellished accounts involving bears, wolves, coyotes and other animals too. Perhaps most interesting is that we appear to be seeing the transmission of deliberately frightening stories that form part of a modern, evolving folklore. It’s not a coincidence that dogman accounts are mostly relayed via podcasts and YouTube channels devoted to the scary and the weird, the very places many of us go to learn about frightening phenomena, places where ‘authenticity’ is ambiguous and sometimes unimportant. The humanoid werewolf did not die out in the 1700s or earlier. It is in fact very much alive and even undergoing a renaissance.

Caption: until recently, the image of werewolves most familiar in popular culture was the human-faced, human-shaped monster of the sort shown here. At left, Lon Chaney as The Wolfman, from the 1941 movie of the same name. At right, a rendition of the same sort of creature from Usborne’s All About Monsters (which I wrote about here). Images: Universal (original here); Usborne/Miller 1977.

Origins of the humanoid werewolf. Having mentioned ‘humanoid werewolves’… the impression prevalent in the literature on monsters is that ‘werewolves’ as believed in during the Middle Ages and beyond were meant to look like large but anatomically normal wolves (Woodward 1991). Of those eyewitness accounts purportedly describing observations of actual werewolves recounted by Baring-Gould (1995) – originally published in 1865 and still regarded as the primary reference on the subject – all describe wolves, not hairy, dog-faced humanoids.

Caption: originally published in 1865, Baring-Gould’s The Book of Werewolves is still the standard reference on werewolves. It interprets accounts as folkloric transmissions (and connected to the long history of ideas that humans might, at times, undergo transformation into the form of another animal), mixed with accounts involving mental illness, and has what feels like a 'modern' approach.

The humanoid werewolf, supposedly, is a 20th century invention connected to cinema, and some authors have implied that it owes its origins to this art form alone (Woodward 1984). The thing is, though: that’s not true. In fact, artwork from the 1600s onwards shows that at least some people were indeed imagining werewolves to be bipedal, and to essentially be dog-headed humanoids. An engraving by George Jacob Schneider, made during the 1680s and connected to a spate of claimed werewolf attacks from Eschenbach in Germany, shows a bipedal werewolf wearing a ragged sheet (Ruickbie 2016). A much-reproduced 18th century engraving – it appears in most 20th century books that discuss the subject of werewolves (e.g., Farson 1975, Bradbury 1981, Grant 1992) – shows a ‘dogman’ werewolf carrying a woman in its jaws.

And a famous illustrating showing werewolves lining up for a nighttime jumping contest – produced for Maurice Sand’s 1858 book Légendes Rustiques – also depicts werewolves of a sort consistent with the modern, pop-culture vision of the creature. This illustration is also a staple of books that cover monsters and related phenomena (e.g., Bradbury 1981).

Caption: at left, a very famous 18th century image showing a werewolf carrying off an unfortunate victim. The point is made that her Christian faith did not save her. At right, werewolves lining up against a cemetery wall in order to compete in a jumping competition: a famous illustration that first appeared in Maurice Sand’s Légendes Rustiques of 1858.

It can be argued that these images were inaccurate in view of what werewolves were really ‘meant’ to be like (Baring-Gould 1995), but the point remains that these humanoid depictions are, and have long been, a staple of the literature. The idea that the humanoid werewolf originated in cinema is, therefore, not true, and we’ve been subjected to this template for some hundreds of years. I put it that this template has persisted to modern times.

The Beast of Seven Chutes. For all the dogman reports that exist, there are no photos or pieces of film. Or, at least, none worth spending any time discussing. But there’s one exception: the June 2005 image that’s become known as the ‘Beast of Seven Chutes’ photo. Taken in Quebec at Le Parc des Sept Chutes (chutes = waterfalls) by a semi-anonymous, French-speaking dump-truck worker named Lary, the photo depicts woodland surrounding a large river. Partly hidden by foliage and shadow at far right, and unnoticed by the photographer at the time, is a large and vaguely humanoid figure standing in a small clearing adjacent to a path.

Caption: Le Parc des Sept Chutes, also known as Sept-Chutes Regional Park or Parc régional des Sept-Chutes, in Lanaudière in the south of Quebec. The eponymous seven waterfalls are located along a 17 km stretch of the Noire River. Image: Google maps.

The figure looks superficially like a dog-faced biped, covered in brown fur and with a whiteish nape and red crown. To its left, adjacent to the lower part of its chest, is what appears to be a distinct, pale object, and if we look really hard we can see that this object has projections that look like legs and a tail. It would appear that the dogman has abducted, and is carrying, a small dog (though other suggestions include a pig, a chunk of meat or a plush toy), a point arguably consistent with eyewitness accounts that describe dogmen holding carrion.

Caption: at left, a close-up shot of the mystery creature, captured accidentally in the photo by semi-anonymous Lary. At right, an extreme blow-up of what is taken to be its face. Images: these are taken from Rob Gaudet’s now defunct website, still findable here via wayback machine.

In current, online cryptozoological theorising (at Cryptid Wiki, for example), there’s the claim that this creature is one and the same as the gugwe, this being a word that comes from Mi’kmaq lore of the Atlantic provinces of Canada. This name is, in fact, more associated with the Seven Chutes photo than ‘dogman’, and I presume that those endorsing this proposal regard gugwe and dogman as the same thing. This is a blatant effort to give dogman’s reality tacit support via supposed connection to an indigenous source, and I don’t see much reason to take it seriously.

Caption: interpretations of the Seven Chutes creature. At left, an impressive effort to visualize the animal’s face as it might look if it were a real animal. A giant, dog-faced primate might be terrifying, but this vision makes it look almost friendly. At right, an effort to show the outlines of the beast if it’s interpreted as a humanoid holding a dog-shaped object. Images: again, I only know these from reddit and have not found their original sources. The artistic reconstruction is credited to someone with a name similar to David A. Cleara. Any help with proper credit is appreciated.

When photos of alleged monsters exist, you must never assume that they’ve gone un-investigated or been deemed of little value or interest. On the contrary, a massive amount of discussion and analysis surrounds these images, and at least some of it has value if you’re interested in knowing what the images really represent. Such is the case here. As documented at a now defunct website and 2023 discussion thread at reddit, author, entrepreneur and humanitarian worker Rob Gaudet looked in detail at this case, made contact with the photographer (initially buying the photo off him, since he was selling it on ebay!), and obtained additional photos and video footage taken at what is undoubtedly the same location.

Caption: Lary’s original photo of Le Parc des Sept Chutes, presumably taken because he was enjoying the look of the white water. Submerged in shadow and vegetation at lower right is a browny-greyish object that looks like a human-sized creature. Image: Lary/Rob Gaudet.

Caption: the same photo but with ‘the creature’ circled in red. Image: Lary/Rob Gaudet.

While the semi-anonymous nature of Lary the photographer and the venue of the discussion – an inactive webpage and a reddit thread – might throw up some red flags, I don’t see a good reason to doubt the veracity of Gaudet’s work and I think that he really did succeed in contacting the photographer as stated.

Based on the interview data that Gaudet obtained, Lary the photographer was alone in the park when the photo was taken, and only noticed the creature when checking his images later on. He was sufficiently intrigued that he later visited the site on three additional occasions, one time taking his girlfriend so that she could stand in the relevant spot to provide a sense of scale. She wasn’t able to stand in the exact same spot due to new vegetation that had grown in the interval, but it’s still evident that ‘the beast’ was approximately human-sized. It also appears that it probably can’t be explained as a misidentified rock, tree stump, fallen log or pile of vegetation since none of those things can or did exist in the specific spot. I think it really must have been an animal of some kind.

Caption: Lary’s photos of the specific location in Le Parc des Sept Chutes where the beast was standing. At left, the original image, with the beast in place. At right, the same location with a person standing – as best as possible – in the same spot. The horizontal lines show how the creature and a person are similar in size. Images: Lary/Rob Gaudet.

Could it be a bear? That doesn’t look right based on its size, shape and posture, since it looks too erect and too broad-chested, and also in the possession of shoulders. These points also rule out wolf, coyote and other known species that might be encountered in the region. What about a non-native, escapee animal? A specific photo of a squatting gorilla has been noted by some as looking similar to ‘the beast’ but, as you can see from the overlay shown below, the similarities are superficial and not impressive. The idea that a gorilla might have been living in the wild in Quebec is unlikely anyway, we have no reason to think that one was in the area at the time the photo was taken, and there’s nothing in the photo that makes it look as if an image of a gorilla has been composited in at some point.

Caption: the photo of a captive Western lowland gorilla Gorilla gorilla gorilla shown here has been linked by some with the Seven Chutes photo. But an overlay of the two shows that the similarity is coincidental since there’s insufficient similarity of shape. The original gorilla image has been flipped, since the source image (published at Wikipedia) shows the animal facing to the right. Image: Greg Hume, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Lary/Rob Gaudet.

What about the most familiar animal of them all, by which I mean… the human. We tend not to see a human-like shape in ‘the beast’, but that’s because we forget (or fail to account for) objects that often accompany humans when they’re out walking in natural areas, like hats, bags and cameras. A sensible and clever interpretation that I find worthy of consideration is that ‘the beast’ is actually a hiker seen from behind, and that what looks like the head and muzzle of ‘the beast’ is a large camera, held upwards because the person was aiming it at an object up in a tree or in the sky.

A claim often made when reinterpretations like this are on offer is that the revisionary ‘gotcha’ is just as speculative and pareidolic as the original monster claim (here, that it’s a giant, dog-headed, furry humanoid carrying an abducted pet dog), but… come on, is it? I feel it likely that, alas, there is no ‘Beast of Seven Chutes’ in the photo, and that we are indeed mis-reading an image of a person.

Caption: at left, another zoom-in showing the beast with, at right, a suggestion interpretation in which the animal is reinterpreted as a person holding a camera aloft. The pale patch is their hair (or headgear), the upper arms, shoulders and sides of the head are the arms and hands of the person, and the muzzle and reddish forehead is a camera body and lens. I do find this interpretation pretty plausible. Images: Lary/Rob Gaudet; I only know the reinterpretation from this reddit page and have been unable to find out who created it originally.

A final piece of alleged dogman evidence is worth mentioning, this being an audio recording where two people – supposedly involved in a late-night collision of their vehicle with an unknown large animal – are attacked by what’s presumed to be the same creature. It’s a noisy, growling beast and, just before the recording cuts out, we hear the desperate screams of its unlucky victims. I certainly haven’t investigated this case in appropriate depth, but I submit that it can be ruled out as an amusing bit of monster theatre.

Explaining dogman. Can there be any rational, real-world, flesh-and-blood interpretation of dogman? Could ‘dogman’ be exactly what some people evidently hope it is: a humanoid canid? That is, a genuine member of the dog family that has evolved a humanoid physique, an obligatorily bipedal stance, and giant size relative to other canids? Linda Godfrey hinted at this idea at times, suggesting that adaptation to a North American habitat dominated by tall grasses had encouraged the evolution of a new, bipedal configuration in wolves. According to this view, people would be seeing a recently evolved, erect-bodied wolf adept at using its forelimbs in grabbing and carrying.

Caption: dogman as envisioned by Tyler Stone, representing a vision of this creature now endorsed by believers. An erect-bodied canid with digitigrade hindlimbs but hominid-like pectoral and forelimb adaptations. Image: Tyler Stone, used with permission.

Is this view scientifically reasonable? The short answer is no. The long answer is that we have no reason to think from fossils, from the functional anatomy of canids living and extinct, or from the role that canids play in ecology (or played, across their whole evolutionary history) that bipedal, semi-bipedal or facultatively bipedal canids might have evolved. Wholly extinct canid groups existed in the past, including the archaic hesperocyonines and the diverse borophagines, the latter sometimes termed bone-crushing dogs. Members of those groups were different from the sole living canid group (Caninae) in some respects, but not so different that we see anything like the evolutionary potential for a ‘non dog’ body plan.

Godfrey’s model also requires that this evolutionary event occurred at breakneck speed within (at most) the last few thousand years. And wolves haven’t been present in North America for more than 30,000 years anyway… a very short time, geologically speaking. We know that profound evolutionary changes can occur in a short timeframe – examples are demonstrated by the cichlid fishes in the great lakes of the African Rift Valley – but no such event is known from the evolutionary history of mammals. Our own species, to take one example, is less than 500,000 years, yet species extremely similar to use in shape and proportions were in existence for more than a million years prior to this.

Caption: we’re basically at a point where those promoting the existence of dogman are endorsing the existence of animals like this… the humanoid werewolf of popular media. These particular figures represent the Victorian werewolf from a 2006 episode of Dr Who, and a 2017 werewolf figure made by Safari Ltd. Image: Darren Naish.

Actual bipedal dogs. Here's a second ‘flesh and blood’ possibility. Despite what I just said, we do, actually, know of fully bipedal canids. The caveat is that I’m referring to malformed individuals of the domestic dog Canis familiaris born without forelimbs, or unlucky enough to have had their forelimbs removed or damaged by accident. Such individuals have had no choice but to walk bipedally. A famous example is Faith, a pet dog who lived in Oklahoma and then Indiana, USA, between 2002 and 2014. We know from other examples that quadrupedal mammals can become bipeds when malformation demands it. The best-known case is that of the bipedal goat described by Everhard J. Slijper in 1942. This animal lacked forelimbs and special attention was paid to its flattened, humanoid chest, modified pelvis and enlarged back muscles (Slijper 1942).

Caption: Faith the bipedal dog (2002-2014) was something of a celebrity, and appeared numerous times on TV and in online articles. She was not swift or agile, but was very much able to walk unassisted. She was born with three limbs, but a deformed forelimb was amputated at age seven months. Images: Mike Matney, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here); (c) Shirley Ann Dennis.

Is it worth considering the possibility that a mutant wolf (or coyote, coywolf, wolf-dog hybrid, or whatever), affected by the same developmental issues, might occur in the wild and hence explain at least some dogman accounts? Two problems affect this hypothesis. The first is that dogman accounts generally make a point of describing large, well-developed forelimbs, so ‘forced’ bipeds these are not. The second is that any hypothetically deformed wild canid is going to be a one-off or, at least, an extremely rare occurrence. There won’t be a number of them spread across a wide area, and there certainly won’t be a self-sustaining population. So… no, I don’t think that malformed or disabled wild-living canids have any contribution to the dogman phenomenon.

The most novel of hybrids. The notion that canids and primates might have hybridized and that dogman is the result – yes, this idea is also hinted at in discussions about dogman – is also a non-starter. Hybridization among mammal species is rampant in the natural world, but it only works when the parent species are sufficiently close behaviourally, physically and genetically. Distantly related species might be compatible when it comes to the relevant physical acts, but hybrid babies are not the result. Canids, for example, cannot produce hybrids with bears, seals, skunks or cats, yet those animals are close relatives of canids compared to primates.

Caption: the idea that bigfoot has been genetically sequenced and has a hybrid origin that involves humans as well as an unknown, mysterious, additional being surely can’t be connected to views that werewolves are real…. can it? Hold my beer. Images: screengrabs from this CFI article on Melba Ketchum.

With that in mind, the notion that anonymous geneticists working in a secret lab might have spliced dog and human DNA together is, for sure, an entertaining or disturbing notion, but also a sci-fi one outside our current abilities. Why any such chimaeric novelty (which would have been extremely expensive to produce and nurture) might be released into the farms and woodlands of the American mid-west is also a question that would need answering. I don’t think that this idea can be taken seriously but I mention it for want of completion. It was promoted by Melba Ketchum (of ‘bigfoot DNA reveals hybrid origin’ fame) in a Coast to Coast interview.

Of mystery kangaroos and devil monkeys. Another idea is that these creatures are not canids with primate-like bodies, but primates with canid-like faces. We know of dog-faced monkeys (drills, baboons and kin). Could there also be big, ape-like, dog-faced primates that await scientific recognition? Again, I think that the short answer is no. However…

Caption: so-called dog-faced monkeys are remarkable animals with a striking and sometimes shocking appearance. Some researchers have speculated that North American primates of this sort actually exist and await recognition. Mandrill Mandrillus sphinx at left, Drill M. leucophaeus at right. Images: Darren Naish.

The notion that North America (and elsewhere) might be inhabited by a large, bipedal or semi-bipedal, dog-faced primate is not new, having first been proposed in the 1970s by cryptozoological investigators seeking to explain animals identified by witnesses as ‘kangaroos’ or ‘devil monkeys’ (Coleman 1998, Coleman & Huyghe 1999). The accounts concerned are vague with little to tie them together. My opinion is that they include observations of escapee wallabies and kangaroos, and that there isn’t a valid category of cryptid here. Perhaps worth noting is that these ‘devil monkeys’ are supposed to be smaller than a person, typically less than 1 m tall, whereas dogman is a giant, at least as big as a human adult if not taller. In other words, the Beast of Bray Road just isn’t at all like the creatures described in alleged ‘devil monkey’ accounts.

Caption: my effort to reconstruct the ‘devil monkey’/’American kangaroo’ cryptid endorsed in parts of the cryptozoological literature (Coleman & Huyghe 1999) and suggested therein to be a kind of dog-faced, bipedal giant monkey. Coleman & Huyghe (1999) proposed that nalusa falaya of the Choctaw of Louisiana represents the same sort of animal, and that these creatures exist “from Alaska to New Brunswick, with a concentration of contemporary sightings in the Mid-west” (p. 60). Image: Darren Naish.

Other cryptozoologists have also suggested a primate identity for dogman, this time that it might be a variant of bigfoot that has a superficially dog-like muzzle and enlarged canines. The ‘gugwe’ term that we saw earlier is applied by some researchers to this alleged bigfoot variant.

My bias – though I don’t think ‘bias’ is the right word – is that I can’t take seriously the hypothesis that North America might be inhabited by a novel mammal species of this size or sort. That’s a view shared with the majority of biologists, naturalists and ecologists.

The bear hypothesis. If we suppose that dogman observations really do describe encounters with real animals, could these be garbled accounts of bears? Bears are not ordinarily bipedal, but they will stand on two legs for a while and some individuals will even walk this way for a while.

Caption: you can decide for yourself how seriously you take this image. The dogman that people are claiming to see is generally supposed to be very distinct from a bipedally-standing bear in a number of important respects. Image: Darren Naish.

An especially bold proponent of dogman might argue that bipedal bears differ from dogmen in that the latter reportedly have prominent shoulders and human-like arms and hands, a most unbear-like anatomical configuration. In addition, bears are plantigrade, meaning that they plant the whole hindfoot on the ground and don’t have ‘hocks’ (bony ankle joints that are raised well up off the ground). That last feature has been mentioned quite specifically by some dogman witnesses and their insistence that the animal they saw was digitigrade and not plantigrade is a problematic contention for the bear hypothesis.

However, that’s not the case across the board. You’ll recall me noting earlier that Mark Schackelman’s Michigan dogman from 1936 apparently had plantigrade feet. In fact, the Schackelman dogman has a few other traits that could be consistent with a bear identity: its strongly flexed wrists (which resulted in the hands hanging down at a 90° angle to the forearm) very much recall those of bipedal bears, and a rounded projection on the outer edge of its wrist looks like the pisiform pad that bears have in the same location (though a dogman that’s a speculative bipedal carnivoran could well have this same feature too).

Caption: underweight, mange-infected Black bears Ursus americanus can look very odd, and with more than a passing similarity to werewolf-type creatures described in certain of the reports. Could witnesses have actually observed bears like the individual shown at left? We also know that bears – some bears, anyway – can walk bipedally. The photo at right shows Pedals, a famous individual from New Jersey that was shot dead in 2016. Note the forelimb pose here and compare it with that of the Schackelman animal shown above. Images: Pennsylvania Game Commission; (c) Ron Cronk.

It’s also worth noting that bears with mange could be relevant to dogman accounts. These unfortunate animals have a skinny appearance where the neck looks thinner than is the case in normal bears and the head looks more clearly demarcated. Parts of the arm, chest and back can be unfurred and exposed, and could create the impression of a pseudo-human body shape. I’m far from the first person to propose this and recall Pat Spain (of the Nat Geo Beast Hunter TV series, and much else besides) suggesting it within recent years.

Does this mean that all dogman accounts are confused descriptions of encounters with bipedally walking bears suffering from mange? No. But some might be.

What, then, to do with dogman? From a sceptical, scientific perspective, there’s no reason to think that there’s a genuine zoological phenomenon here. There are no bones or other remains, and no worthwhile photographic evidence. There are no otherwise-unexplained DNA, hair or scat samples, audio recordings, or tracks or bite marks that require the serious consideration of dogman as a real animal. It’s a pop-culture, folkloric phenomenon, the ‘evidence’ being a tainted pool of dodgy accounts collected by people who’ve been specifically looking for weird tales to relate in popular books and articles, and in podcasts.

Caption: yes, that’s a Linda Godfrey action figure, photographed by Loren Coleman and part of the collection on show at the International Cryptozoology Museum. Part of me disapproves of the lionization, even canonization, gifted to investigators of cryptozoology. They’re often not heroic at all and are sometimes in it for self-aggrandizement, not philanthropy! But another part of me likes action figures and geeky humour. Image: Loren Coleman.

Hypotheses that dogman might be explained by a recently evolved, novel form of canid or developmentally aberrant wild-living canid specimens don’t withstand scrutiny and shouldn’t be endorsed, and notions of a hybrid or lab-born origin are pseudoscience pushed by unreliable narrators.

Dogman, beloved of anti-science types. My personal opinion is that this phenomenon persists for two reasons. The first is that some people – often, those who promote the idea that the scientific consensus fails to explain the real nature of the universe – very much want inexplicable creatures of this sort to exist. It fits within a “science can’t explain everything, the world is stranger than we know, scientists are only in it for the money” worldview aligned with conspiracy theory and anti-science feelings, and a cynical take could be that it’s symptomatic of the poor science literacy and aggressive, right-leaning libertarianism prevalent in parts of the USA. I’ve seen this anti-scientific view pushed on pro-cryptozoology podcasts (thinking in particular of Wes Germer’s Sasquatch Chronicles, sorry Wes), and also by researchers who promote anti-scientific views (like Melba Ketchum).

Caption: discussions and stories relating to dogman and American werewolves do appear in printed media, but their primary theatre is the internet, YouTube and the podcasting world in particular. Move in the right circles, and you will be constantly subjected to dogman lore and discussion.

I have some fondness and respect for Linda Godfrey, but like many writers who make or made a living from the generation of content on weird phenomena, she was guilty of mystery-mongering: of maintaining and building interest in dogman through what amounts to constant promotion.

The second reason is the sociocultural one I’ve pushed before with respect to monster sightings and belief (Naish 2016, 2023). Dogman witnesses are not reporting their claimed observations as encounters with an entirely new, unfamiliar creature, but – on the contrary – are describing something deeply familiar and very much ‘known’; the dog-headed, humanoid werewolf of cinema, literature and mythology. As others have noted before me, dogman reports have been coming in at about the same time as humanoid werewolves have been making a minor resurgence in the cinema: the Canadian movie Ginger Snaps saw release in 2000, and the very successful UK horror flick Dog Soldiers was outed in 2002. Creatures of this sort were very much in people’s minds.

Caption: the dog-headed humanoid is a very familiar image these days, thanks in no small part to memorable creatures from cinema. At left, a werewolf as portrayed in Ginger Snaps of 2000. At right, a Scottish werewolf as seen in Dog Soldiers of 2002.

Is dogman ‘real’? It’s real and alive in modern culture, for sure, and in fact this is a fascinating case of evolving folklore, very much worthy of analysis and investigation. But is it a flesh-and-blood creature that walks the land and awaits scientific recognition? No.

For previous Tet Zoo article on monsters, cryptozoology, folklore and connected issues, see…

Bigfoot’s Genitals: What Do We Know?, August 2018

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness, August 2019

Lore of the Loveland Frog, January 2020

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos, August 2020

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, October 2020

The Lake Dakataua ‘Migo’ Lake Monster Footage of 1994, February 2021

What Was the Montauk Monster? A Look Back to 2008, October 2021

Santa Cruz’s Duck-Billed Elephant Monster, Definitively Identified, November 2021

Legend of the Black Dog, August 2022

Acknowledgments. This article was first published at my patreon and I benefitted from comments added by patrons. Thanks also to Sharon Hill and Jeb Card for comments and corrections, and Tyler Stone for kind use of images.

Refs - -

Baring-Gould, S. 1995. The Book of Werewolves. Senate, London.

Bradbury, W. 1981. Into the Unknown. The Reader’s Digest Association, Pleasantville, New York/Montreal.

Coleman, L. 1998. The Wisconsin werewolf. Fortean Times 108, 47.

Coleman, L. & Huyghe, P. 1999. The Field Guide to Bigfoot, Yeti, and Other Mystery Primates Worldwide. Avon Books, New York.

DeMello, M. 2023. Bigfoot to Mothman: A Global Encyclopedia of Legendary Beasts and Monsters. Bloomsbury Academic, New York.

Farson, D. 1975. Vampires, Zombies, and Monster Men. Aldus Books, London.

Godfrey, L. 2003. The Beast of Bray Road: Tailing Wisconsin’s Werewolf. Linda Godfrey.

Godfrey, L. 2012. Real Wolfmen: True Encounters in Modern America. Tarcher/Penguin, New York.

Grant, J. 1992. Monster Mysteries. The Apple Press, London.

Naish, D. 2016. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Naish, D. 2022. A cultural phenomenon. The Biologist 69 (3), 16-21.

Ruickbie, L. 2016. The Impossible Zoo: An Encyclopedia of Fabulous Beasts and Mythical Monsters. Robinson, London.

Slijper E. J. 1942. Biologic-anatomical investigations on the bipedal gait and upright posture in mammals, with special reference to a little goat, born without forelegs. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie Van Wetenschappen 45, 288-295, 407-415.

Woodward, I. 1991. Delusions and transformations. In Brookesmith, P. (ed) Creatures from Elsewhere: Weird Animals That No-One Can Explain. Macdonald & Co, London, pp. 81-84.