I’ve surely said on several occasions over the years that I’ve never written enough about rodents here at TetZoo. But, then, you could write about nothing BUT rodents and still not write about them enough… there are just so many of them, both in terms of numbers of species and individuals. Whatever, I’ve opted today to write about cloudrunners and other cloud rats, a group of luxuriantly furred, large, striking members of Muridae – the rat and mouse family – endemic to the Philippines.

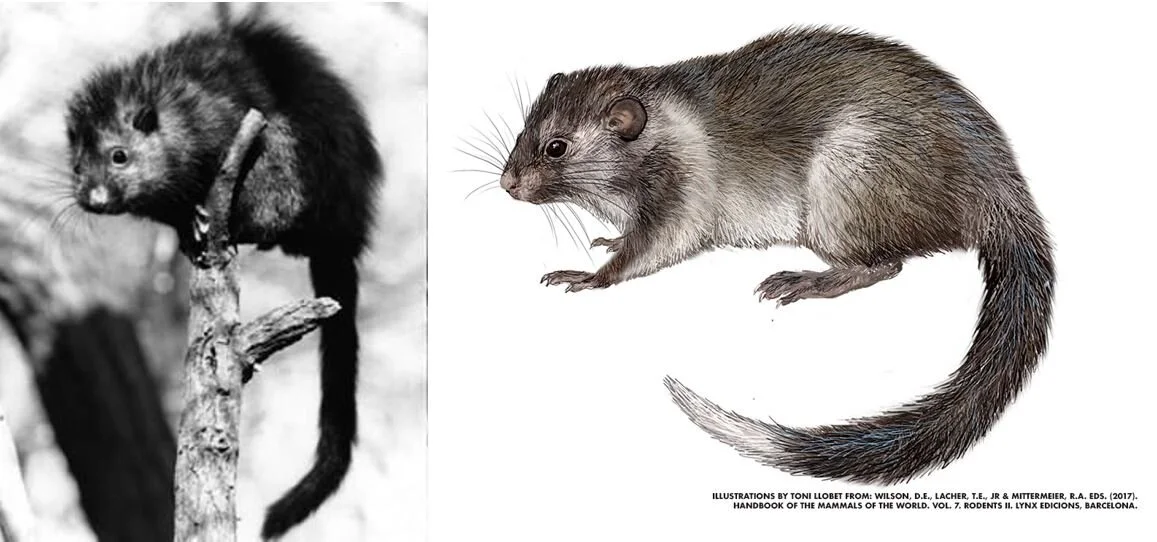

Caption: colour variation within the luxuriantly furred Bushy-tailed cloudrunner, Giant bushy-tailed cloudrunner or Luzon bushy-tailed cloud rat Crateromys schadenbergi. Image: Adolph Bernhard Meyer, public domain.

Cloud rats are a small group containing at least four extant species, all included within the genus Crateromys. The name cloudrunner is used by some authors for a specific sub-group of cloud rats, and as an interchangeable name for ‘cloud rat’ by others. Whatever, they really are spectacular rats, in cases reaching 87 cm in total length and over 1.5 kg. The best known and largest member of the group – the Bushy-tailed cloudrunner, Giant bushy-tailed cloudrunner or Luzon bushy-tailed cloud rat C. schadenbergi – is covered in long, soft fur that grows from the whole of the tail (a unique feature for a murid) in addition to the head, body and limbs. The pelt is rougher and coarser in the other species and the tail is less luxuriant. Colour is variable from one species to the next but they tend to be dark brown or black on their upperparts and a lighter brown or grey ventrally. The pelt of the Bushy-tailed cloudrunner at least is sought after and sold in markets in Baguio, Luzon (Nowak 1999). Regarding the rest of the anatomy, the muzzle is proportionally short and slender, the eyes and ears are relatively small, and both the hands and feet are pentadactyl and all except the thumbs (which have nails) are equipped with slender claws.

Caption: the Bushy-tailed cloudrunner (at left) is truly an extreme murid, look at that tail! This taxiderm specimen was figured by Musser et al. (1985). Other species, like this Panay cloudrunner (right), are less extreme. Images: Musser et al. (1985); Petr Hamerník, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Overall, cloud rats look vaguely squirrel-like, and they may indeed occupy the niche occupied by squirrels elsewhere, since squirrels are absent from at least some of the islands where cloud rats occur. They’re nocturnal, mostly arboreal, and predominantly herbivorous, the diet including papayas, bananas, guavas and leaves. They’re easy to feed in captivity and will readily eat sunflower seeds, mulberry leaves, cabbage and other widely available plants (Gonzales & Kennedy 1996). They build large stick nests high up in trees, in particular in oaks and pines.

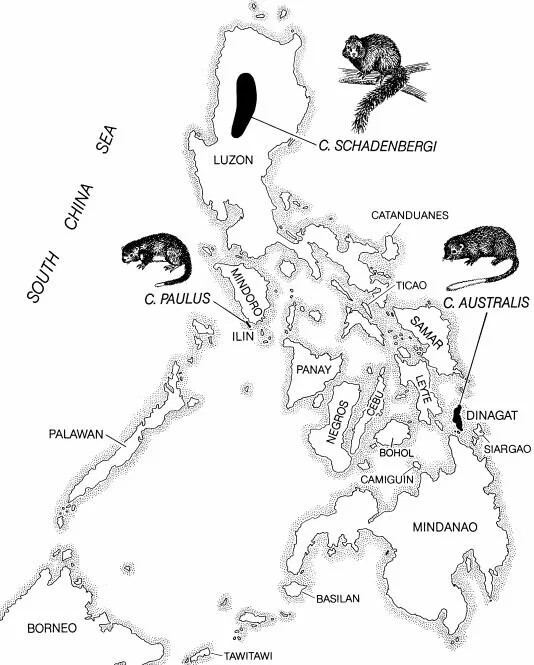

Crateromys was first named by the British mammalogist Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas in 1895 (the type species is C. schadenbergi of northern Luzon), and not until 1981 was a second species discovered. This is the Ilin Island cloudrunner C. paulus, the type specimen of which was actually collected in 1953 (Musser & Gordon 1981). A third species – the Dinagat cloud rat C. australis, endemic to Dinagat in the far east of the Philippine archipelago – was named in 1985 for a specimen collected in 1975 (Musser et al. 1985). This species then disappeared for a while (and was suspected to be extinct) but five live individuals were photographed and filmed in 2012. A fourth species – the Panay cloudrunner C. heaneyi – was scientifically named in 1996, this time for a specimen collected in 1987 (Gonzales & Kennedy 1996). You’ll observe that science is slow, often for good reason.

Caption: Ilin Island cloudrunner C. paulus in life, and as illustrated by Toni Llobet for the Handbook of the Mammals of the World, Volume 7. Images: (c) Toni Llobet.

What does this distribution tell us about cloud rat history in the Philippines? The fact that most species occur in the northern part of the archipelago suggests that they moved into the area from the north, an idea consistent with other evidence (Musser & Heaney 1992). We’ll come back to this subject in a moment. Note also that the Dinagat species is the only cloud rat from the southern Philippines. Incidentally, a few other new mammals were discovered on the same 1975 expedition that led to the technical recognition of the Dinagat species, namely the Dinagat moonrat Podogymnura aureospinula and Dinagat hairy-tailed rat Batomys russatus.

Caption: at left, the holotype of the Dinagat cloud rat Crateromys australis Musser et al., 1985, an adult male c 55 cm long in total. At right: the skulls of (top to bottom) C. schadenbergi, C. australis and C. paulus to scale. The species obviously differ in size. Images: Musser et al. (1985).

Anyway… the presence of cloud rats on Dinagat could mean that other species await discovery on those islands located between Dinagat and those more northerly islands where the other species occur, among them Samar and Leyte, and perhaps Cebu and Mindoro. Panay is one such island where we might predict their occurrence, and it’s a place where (post-1996) we now know they occur. It could also be that cloud rats occurred on some or all of those islands in the past and are now extinct on them. And, of course, there might still be other species awaiting discovery on other islands, like Catanduanes and Ticao (both of which are close to Luzon), and even in southern Luzon.

Caption: this map from Musser et al. (1985) shows how the presence of cloud rats on Dinagat might suggest their presence on Panay and elsewhere in the archipelago… Image: Musser et al. (1985).

One thing often mentioned about cloud rats is their ability to vocalise. The Bushy-tailed cloudrunner makes shrill calls sometimes likened to those of certain insects (Nowak 1999). Captive Panay cloudrunners have been reported to make grunts when approached by humans, though a captive specimens who did this changed after a few days to a “fine, almost inaudible, whistling-like “psssst” heard often at feeding time” (Gonzales & Kennedy 1996, p. 39), which suggests rapid acclimatisation to human proximity.

While researching cloudrunners I’ve been slightly frustrated to find that the word cloudrunner has been applied to a band and a brand of running shoe, meaning that the animals are essentially a no-show in internet searches (unless you add additional terms, like ‘cloudrunner Muridae’ or such). This happens with quite a few terms relevant to the natural world – snow leopard (a piece of software), amazon and catfish (a TV show) are among them – and it might be argued that it’s detrimental to conservation awareness and public education relevant to those things.

Caption: other members of the Philippine clade that include Crateromys are also spectacular. This is the Southern giant slender-tailed cloud rat Phloeomys cumingi, Image: Jaroslav Vogeltanz, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Where does Crateromys belong within the murid family tree? It’s been thought for decades that cloud rats are close to Batomys (the Luzon and Mindanao forest rats) and Carpomys (the Luzon rats) (Musser & Heaney 1992) and probably Phloeomys (the slender-tailed cloud rats) too (Jansa et al. 2006). In other words, they belong to a ‘Philippine Old Endemic’ group termed Phloeomyini (Lecompte et al. 2008, Steppan & Schenk 2017) and do not have close phylogenetic ties with the murids of Australasia, nor indeed with a second Philippine murid group – the ‘Chrotomys division’ of Musser & Carleton (2005) – that does appear to have affinities with the Australasian murids. Excluding the ‘Chrotomys division’ murids from the Old Endemic clade contradicts previous ideas (e.g., Musser & Heaney 1992). I’ve written about Chrotomys (the Luzon striped mice, shreats or shrew rats) before and about the Australasian murids before, by the way (see links below).

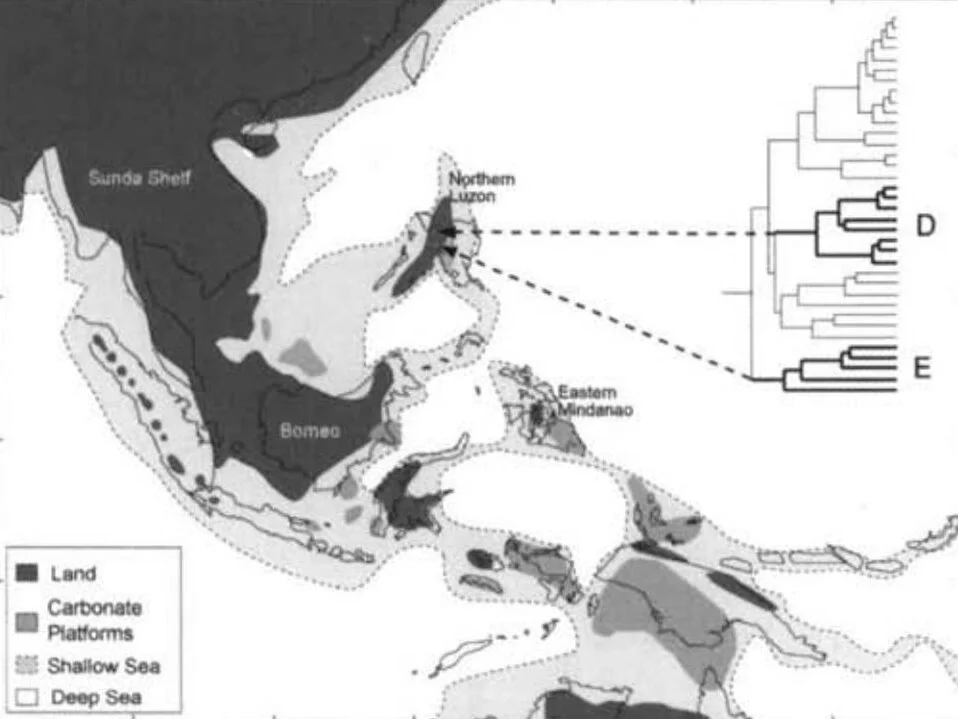

Caption: Jansa et al. (2006) found northern Luzon to be the place where ‘Old Endemic’ Philippine murids (‘E’ in the cladogram) have their centre of distribution. At the time shown in this map (about 15 million years ago), the northern Philippines were separated from the southern islands by deepwater channels, so migration to that southern section likely happened later on. Image: Jansa et al. (2006).

Murids thus invaded the Philippines in two major waves, with Phloeomyini being an especially old clade that diverged early in murine history (seemingly around 15 million years ago, during the middle Miocene) and lacks close living relatives. The other Philippine murids are far younger. In fact Phloeomyini seems to be the sister-group to the whole of the remainder of Murinae (the ‘core murine’ clade; this contains all murids excepting gerbillines and deomyines) (Jansa & Weksler 2004, Steppan et al. 2005, Jansa et al. 2006, Lecompte et al. 2008, Steppan & Schenk 2017). I need to create some cladograms that depict the relationships among these groups… bear with me.

Also worth noting is that Luzon is the phloeomyine centre of distribution, and that Luzon was actually well separated from the remainder of the Philippines when the group must have colonised the region (Jansa et al. 2006). The time concerned – the middle Miocene – was one of exceptionally high sea levels and the drowning of many lowland regions, so ancestral phloeomyines may well have rafted to Luzon, not crossed via a landbridge. All of this is consistent with invasion from the Sunda Shelf region; it also means that phloeomyines can only have moved to the southerly parts of the Philippines later on in history (once various tectonic events moved the southern Philippines northward), and also that their diversification happened within the Philippine archipelago.

Caption: TetZoo tries to do justice to muroid rodents, it really does! More are coming… Images from the in-prep textbook.

The bad news on these marvellous animals is that they’re threatened by forest destruction, and to a lesser degree by hunting and by destruction associated with the mining industry. Obviously, they’re mostly dependant on trees and at least a few specimens (including holotypes, like that of the Panay cloudrunner) have been discovered in tree stands otherwise surrounded by deforested grassland. Both the Panay and Ilin species are currently classed as endangered by the IUCN, and the other two are classes as ‘data deficient’… which means that sufficient information has yet to be collected, not that the species are ok.

Rats, mice and other muroid rodents have been covered at TetZoo a few times before, and they’ll be covered a few more time yet, oh yes…

Osgood, Fuertes, and mice that swim and mice that wade, March 2006

Australia, land of placentals (part I), December 2007

Australia, land of placentals (part II), December 2007

New, obscure, and nearly extinct rodents of South America, and… when fossils come alive, November 2008

Of vole plagues and hip glands, January 2014

North America: land of obscure, freaky voles, January 2014

A brief history of muskrats, September 2014

Cricetomyines: the African pouched rats and mice, November 2014

African Climbing Mice and the Congo Link Rat, October 2015

Meet the Shreats, July 2016

The Sigmodontines, March 2017

Refs - -

Gonzales, P. C. & Kennedy, R. S. 1996. A new species of Crateromys (Rodentia: Muridae) from Panay, Philippines. Journal of Mammalogy 77, 25-40.

Jansa, S. A., Barker, F. K. & Heaney, L.R. 2006. The pattern and timing of diversification of Philippine endemic rodents: evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Systematic Biology 55, 73-88.

Jansa, S. A. & Weksler, M. 2004. Phylogeny of muroid rodents: relationships within and among major lineages as determined by IRBP gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 31, 256-276.

Lecompte, E., Aplin, K., Denys, C., Catzeflis, F., Chades, M. & Chevret, P. 2008. Phylogeny and biogeography of African Murinae based on mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences, with a new tribal classification of the subfamily. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2008, 8: 199.

Musser, G. G. & Carleton, M. D. 2005. Superfamily Muroidea. In Wilson, D. E & Reeder, D. M. (eds) Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 2. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, pp. 894-1531.

Musser, G. G. & Gordon, L. K. 1981. A new species of Crateromys (Muridae) from the Philippines. Journal of Mammalogy 62, 513-525.

Musser, G. G. & Heaney, L. R. 1992. Philippine rodents: definitions of Tarsomys and Limnomys plus a preliminary assessment of phylogenetic patterns among native Philippine murines (Murinae, Muridae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 211, 1-138.

Musser, G. G., Heaney, L. R. & Rabor D. S. 1985. Philippine rats: a new species of Crateromys from Dinagat Island. American Museum Novitates 2821, 1-25.

Steppan, S. J., Adkins, R. M., Spinks, P. Q. & Hale, C. 2005. Multigene phylogeny of the Old World mice, Murinae, reveals distinct geographic lineages and the declining utility of mitochondrial genes compared to nuclear genes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37, 370-388.