Frogs and toads – anurans – have profoundly modified skeletons and are among the most atypical of tetrapods... (this article was first published at ver 3 in December 2016; original here)…

Here’s something I’ve come back to on a few occasions at Tet Zoo; it's something that needs to be said as often as possible, as it’s pretty amazing. Frogs and toads – collectively, anurans – are really, really weird. They’re among the weirdest of all tetrapods, in fact. And while that statement might be applied to knowledge of their reproductive diversity or the diversity of their larvae (aka tadpoles), today I’m applying it to their skeletons.

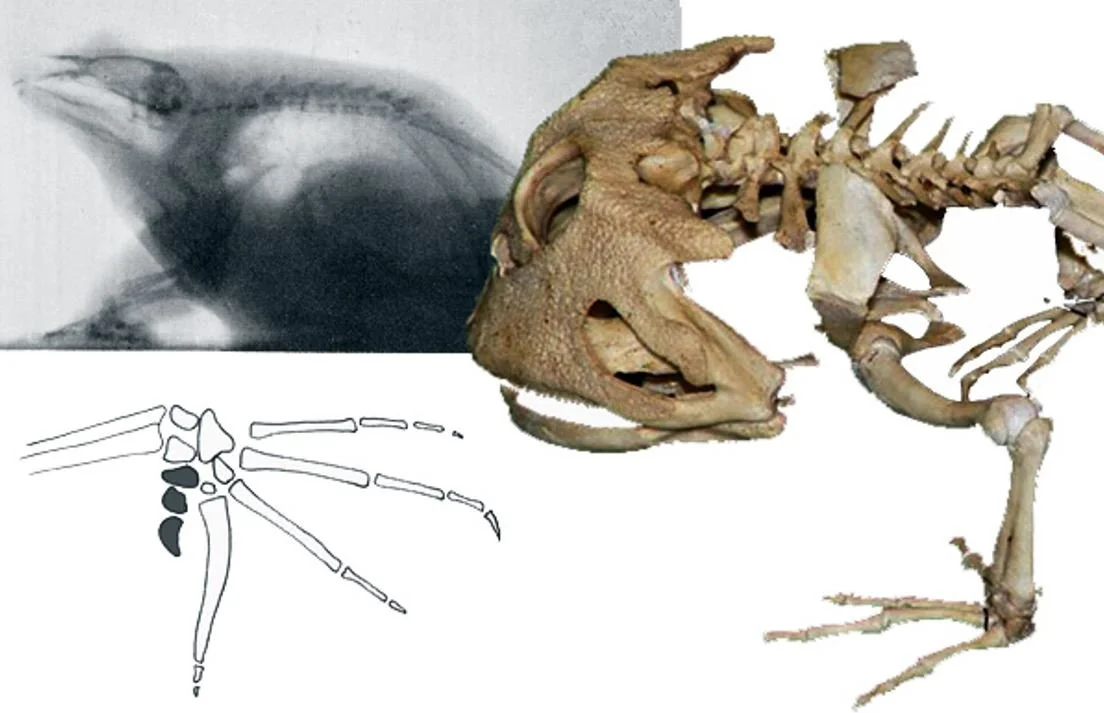

Caption: if you're lucky enough to find a frog or toad skeleton - something I've done on several occasions - you might be surprised by how few bones there are. This skeleton, discovered among leaf litter in Cornwall, southern England, belongs to Rana temporaria. Image: Darren Naish.

Anuran skeletons are weird for several reasons: because they’re massively ‘reduced’ (in terms of numbers of elements and areas of ossification) relative to those of other tetrapods, because they’re weirdly archaic (they retain a few bits and pieces that are otherwise lacking in modern tetrapods), and because they’re novel and highly specialised (with substantially modified anatomical configurations in parts of their skeletons). Let’s look at the specifics. I should note that the features discussed here are typical of ‘modern’ anurans (or crown-anurans); they are not the case in some of the earliest members of the anuran lineage.

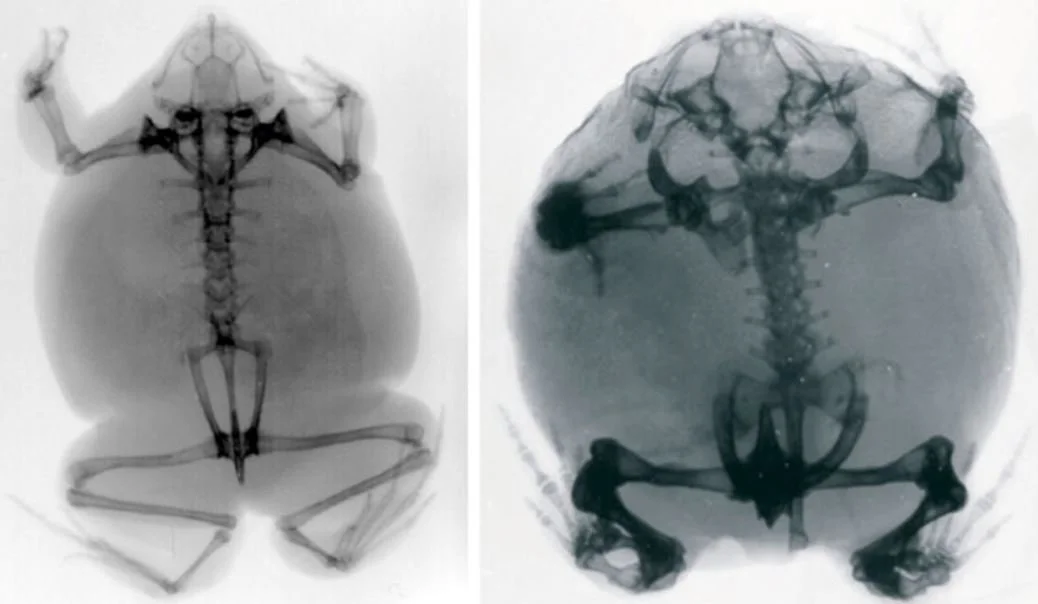

Caption: x-rays of the weird African frogs Hemisus (left) and Breviceps (right). It won't be lost on you how small the skeleton is compared to the size of the whole animal. Image: van Dijk (2001).

The anuran skull is notable for the relatively few elements it contains: elements typically present in tetrapod skulls have been lost, or fused with adjacent structures. Most of the skull roof is formed of the giant frontoparietal complex which typically starts out as a paired structure but ends up a giant plate forming the region between the large eye sockets. The palate is what we term highly fenestrated, meaning that most of its surface is occupied by enormous spaces. Virtually all anurans lack a dentition in the lower jaw, the weird exception being the marsupial treefrog Gastrotheca. As mentioned here at Tet Zoo before (see links below), Gastrotheca simply must have re-evolved these teeth from ancestors that lacked them, an unambiguous case of re-evolution of a ‘lost’ structure. Tooth-like structures – so-called odontoids – have evolved on a few occasions (Fabrezi & Emerson 2003).

Caption: the tremendously abbreviated vertebral column of a modern anuran: in this case that of Leptodactylus. Excluding the urostyle, there are just 9 vertebrae here. 'p' = process. Scale bar = 2 mm. Image: Ponssa (2008).

The anuran vertebral column is substantially reduced: anurans have (at most) nine presacral vertebrae, and some have as few as five. The sacrum involves just a single vertebra that has a pair of stout transverse processes: their junction with the pelvis (on which read on) is mobile, sometimes highly so (Whiting 1961). Ribs are either highly reduced or absent. That’s right: no ribs. Obviously, anurans don’t employ costal ventilation in breathing (that is, use of the ribs in operating the lungs). They instead rely on buccal pumping, where movement of throat musculature controls inhalation and exhalation.

Caption: hands of the Australian myobatrachid Limnodynastes tasmaniensis showing sexual dimorphism in the presence in the prepollex. Diagrams based on those in Galis et al. (2001). Image: Darren Naish.

Anuran limbs and limb girdles are also odd compared to those of other tetrapods. Anurans have four fingers, but are these digits I-IV or II-V? An additional structure termed the prepollex has been interpreted as the true digit I by some authors, in which case the large digits are II-V. However, developmental data shows that the prepollex is a novelty related to increased ossification in the fingers (Fabrezi 2001). This structure is often large and complex and there are even frogs (like the treefrog Hysiboas andinus) where it is a large, curved spike that protrudes from the skin; in others its shape and even its presence is sexually dimorphic. A similar structure – the prehallux – is present in the foot. Again, there are times when it has been interpreted as a true digit, a conclusion that would make anurans hexadactyl (Galis et al. 2001).

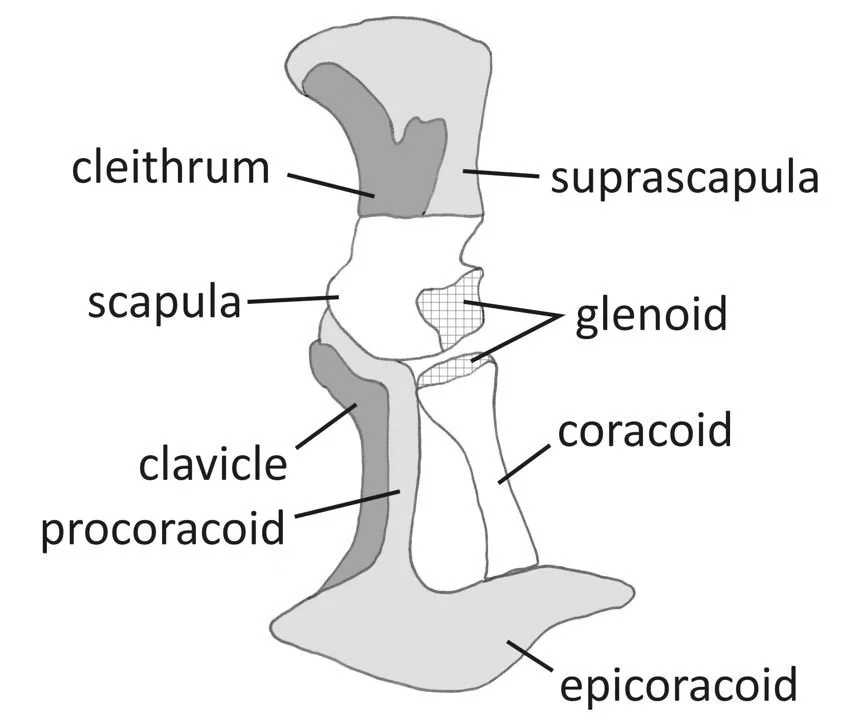

Caption: skeletal architecture of the anuran scapulocoracoid, specifically that of Discoglossus. Based on a diagram in Havelková & Roček (2006). Image: Darren Naish.

The radius and ulna are fused together, forming a compound element termed the radioulna. Meanwhile, the bones of the pectoral girdle are complex and complimented by an assortment of new elements. The paired clavicles and coracoids are transverse bars, separated along the midline by the epicoracoid cartilages and sternum/xiphisternum. The omosternum projects anteriorly from the junction of the clavicles, and the procoracoids are attached to both the posterior margins of the clavicles and the epicoracoid. In some anurans, the epicoracoid cartilages are obviously paired and both components distinctly overlap on the midline, forming what’s known as the arciferal condition. In others, the epicoracoid cartilages are fused at the midline, forming the firmisternal condition. Both a cleithrum and a cartilaginous suprascapula are present dorsal to the scapula (Havelková & Roček 2006): the anuran cleithrum is a relict and much less important in size and shape than it is in temnospondyls and other fossil relatives of anurans. The omosternum and xiphisternum appear to be new structures that might have a role in shock absorption. A midline element present in anuran ancestors – the interclavicles – is absent.

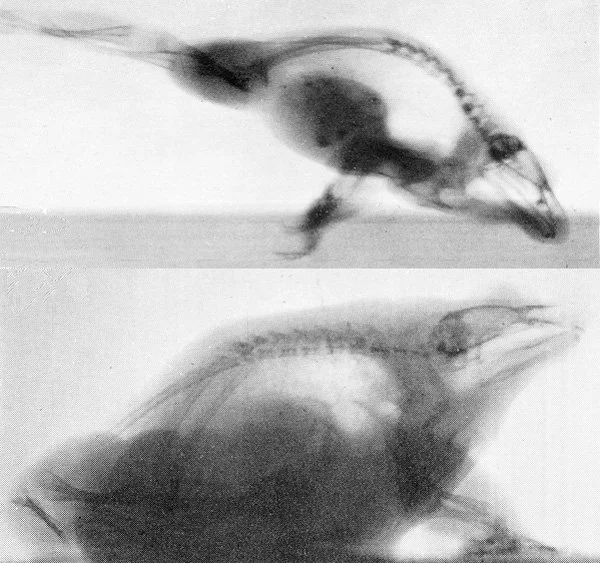

Caption: x-rays of two anuran species: Rana temporaria at top, Discoglossus pictus below. As the ilium pivots on the sacral vertebra, it rotates. At top, you should be able to see how the urostyle and ilium are almost parallel when the hindlimbs are flexed. At bottom, the urostyle and ilium are at an obvious angle when the limbs are at rest. Image: Whiting (1961).

The anuran pelvis consists of a cylindrical, rod-like central unit (the urostyle) surrounded by two super-long, shaft-like ilia. Reduced, plate-like (and typically unossified) pubic bones are present beneath the ilia and paired, cartilaginous prepubic or epipubic bones are sometimes present too. The ilia rotate during development: they start out with a vertical orientation (the ancestral, ‘normal’ condition for tetrapods) but end up with their long axes near-parallel to the vertebral column (Ročkocá & Roček 2005). A consequence of this rotation is that the acetabulum (the hip socket) is located far posterior to the sacrum, and in fact is about level with the position of the tail (Ročkocá & Roček 2005).

Caption: skeleton of a Ceratophrys. The giant, rod-like ilia - arranged on either side of the rod-like urostyle - should be obvious. Image: Mokele Wikipedia (CC BY 3.0).

That rod-like structure in between the two halves of the pelvis – the urostyle – looks (to people more familiar with the osteology of other tetrapod groups) to be a fused, simplified set of sacral and dorsal vertebrae, but it’s weirder than that: it actually incorporates both an ossified hypochord, the sheath that surrounds the spinal cord, and three or four fused caudal vertebrae. That’s right, developmental studies have shown that adult anurans do possess caudal vertebrae (Ročkocá & Roček 2005), albeit caudal vertebrae that are fully incorporated into an utterly unique, rod-like structure where all distinguishing features have been obliterated.

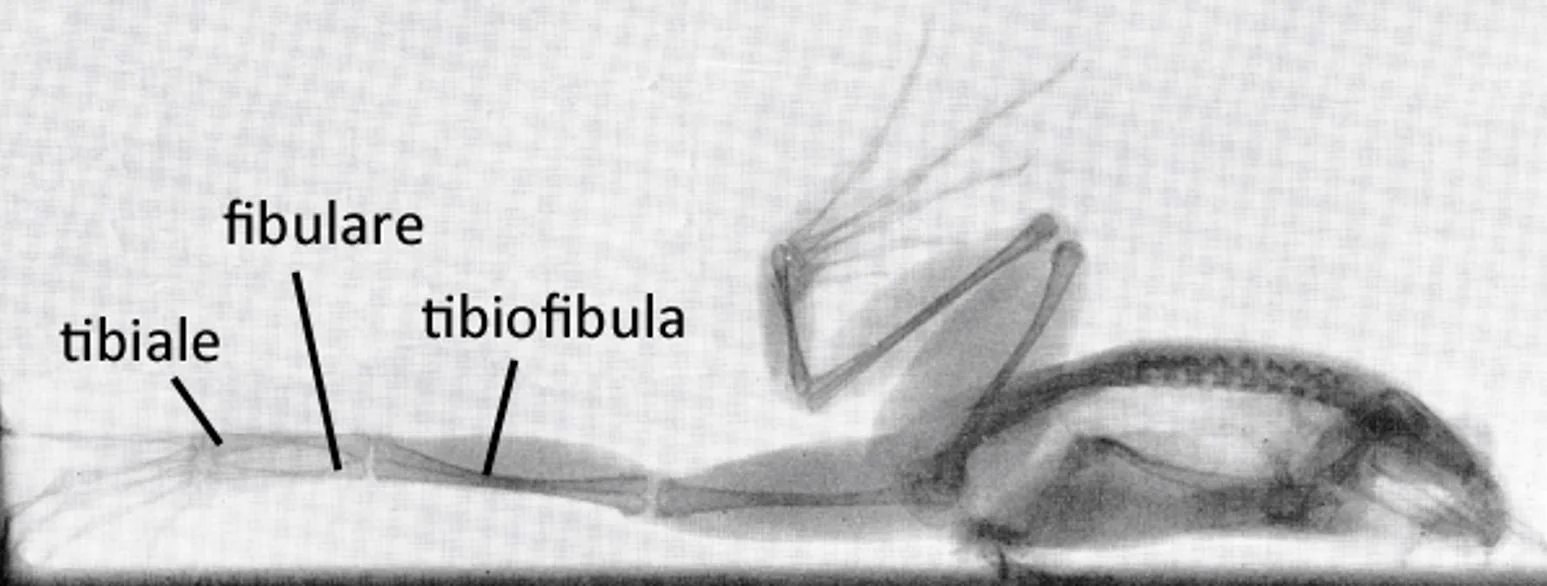

Caption: a Rana frog in x-ray showing key bony elements of the hindlimb. The original version of this image is vertical - the frog is actually standing on tip-toes. Image: Whiting (1961).

Anuran hindlimbs are generally highly elongate. The tibia and fibula are fused together, forming another compound structure termed the tibiofibula, while the proximal tarsal bones have become elongate, tibia- and fibula-like structures (termed the tibiale and fibulare) that effectively function as an additional limb segment.

So, there we have it. This is one of the weirdest, most profoundly modified skeletal plans in the whole of Tetrapoda: it is, we think, highly specialised for jumping, and the inheritance and retention of this bauplan means that anurans are, as a group, rather uniform. It also means that anurans are in no way standard models for what a tetrapod is like.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on frogs and toads, see...

In pursuit of Romanian frogs (part II: WESTERN PALAEARCTIC WATER FROGS!!), July 2011

In pursuit of Romanian frogs (part III: brown frogs), August 2011

The toads series comes to SciAm: because Africa has toads too, September 2011

20-chromosome toads, September 2011

Glassfrogs: translucent skin, green bones, arm spines, January 2013

Everybody loves glassfrogs, February 2013

African tree toads, smalltongue toads, four-digit toads, red-backed toads: yes, a whole load of obscure African toads, December 2014

Parsley frogs: spadefoots without spades, December 2014

Megophrys: so much more than Megophrys nasuta, December 2014

North American spadefoot toads and their incredible fast-metamorphosing, polymorphic tadpoles, January 2015

Tadpole nests, past and present, January 2015

Gladiatorial glassfrogs, redux, January 2015

Frogs you may not have heard of: Brazil’s Cycloramphus ‘button frogs’, January 2015

There is so much more to flying frogs than flying frogs, January 2015

A Brief Introduction to Reed, Sedge and Lily Frogs, January 2015

‘Strange bedfellow frogs’ (part I): rotund, adorable brevicipitids, January 2015

'Strange bedfellow frogs' (part II): pig-nosed or shovel-nosed frogs, or snout-burrowers, February 2015

It’s the Helmeted water toad… this time, with information!, January 2016

The Remarkably Weird Skeletons of Frogs, December 2016

A Love Letter to the Common Frog, August 2020

Allodapanura, the Biggest Frog Group You’ve Never Heard Of (Part 1), October 2020

Tiny Frogs and Giant Spiders: Best of Friends, August 2022

Refs - -

Fabrezi, M. 2001. A survey of prepollex and prehallux variation in anuran limbs. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 131, 227-248.

Fabrezi, M. & Emerson, S. B. 2003. Parallelism and convergence in anuran fangs. Journal of Zoology 260, 41-51.

Galis, F., van Alphen, J. J. M. & Metz, J. A. J. 2001. Why five fingers? Evolutionary constraints on digit numbers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 16, 637-646.

Havelková, P. & Roček, Z. 2006. Transformation of the pectoral girdle in the evolutionary origin of frogs: insights from the primitive anuran Discoglossus. Journal of Anatomy 209, 1-11.

Ponssa, M. L. 2008. Cladistic analysis and osteological descriptions of the frog species in the Leptodactylus fuscus species group (Anura, Leptodactylidae). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 46, 249-226.

Ročkocá, H. & Roček, Z. 2005. Development of the pelvis and posterior part of the vertebral column in the Anura. Journal of Anatomy 206, 17-35.

van Dijk, D. E. 2001. Osteology of the ranoid burrowing African anurans Breviceps and Hemisus. African Zoology 36, 137-141.

Whiting, H. P. 1961. Pelvic girdle in amphibian locomotion. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London 5, 43-57.