Giant tortoises are among the most remarkable of reptiles to have ever evolved….

Caption: I’m not lucky enough to have ever seen any giant tortoises in the wild. In fact, I’ve never seen any tortoises, of any sort, in the wild, ever. But here are some captive and museum giant tortoises I have seen. Images: Darren Naish.

I don’t know how I’m going to justify that statement but I’ll leave it there as it is, so let’s just live with it. I like giant tortoises enough that I’ve had reason to write about them a few times here in the past (see links below). But while the living species are very nice and all, they do sort of pale in comparison to their extinct giant relative: Megalochelys, a geologically long-lived Eurasian taxon that was alive during the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene and lived from central Asia (and perhaps eastern Europe) in the west to Indonesia in the east, including Borneo and Sulawesi. Recent finds indicate that it also occurred in the Philippines.

Caption: the very familiar mounted Megalochelys (AMNH 6332) on show at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. This specimen was collected by Barnum Brown in the Siwalik Hills of India in 1922 and was restored from thousands of fragments likened to the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Some of the features here are not especially realistic (look at those hands) but others are close to reality: note the forked epiplastral structure at the front of the plastron, the tall, ‘sawn off’, steep-fronted nose, and the wide, oval anterior opening to the shell. Image: Claire Houck, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

You might know this tortoise better as Colossochelys, the name that was in use for much of the 20th century and the one still prevalent in books that discuss or mention it. But Megalochelys has nomenclatural priority, having been published by Hugh Falconer and Thomas Cautley in 1837. Colossochelys was published by the same authors in 1844. The reason that Colossochelys won out (for a while) was not exactly empirical: Murchison (1868, p. 359), in notes attached to Falconer’s never-finished c 1837 memoir on the animal*, noted that Megalochelys was abandoned because it “was thought not to convey a sufficiently expressive idea of the size”!

* Falconer died in 1865 and left behind a substantial volume of notes on fossils he had been studying from the Indian Siwalik Hills. This work was tidied up and published in two volumes by Charles Murchison, both published in 1868.

Caption: back in 2021, I published two articles on the occasional carrion-eating proclivities of tortoises. Hodari Nundu was sufficiently inspired to produce this excellent illustration, in which a Megalochelys disputes carcass ownership with the hyaenid Pachycrocuta. The venue is Pleistocene south Asia. Image: Hodari Nundu, used with permission.

An additional issue affecting the nomenclature of these tortoises is that they were – like virtually all big tortoises living and extinct – subsumed at times into the super-inclusive catch-all versions of Testudo and Geochelone that were once in fashion. Those names are, today, restricted to specific lineages within the tortoise family (the type species for Testudo is the Spur-thighed tortoise T. graeca, and that for Geochelone is the Indian star tortoise G. elegans) and we now use a system where multiple genus-level names are in use.

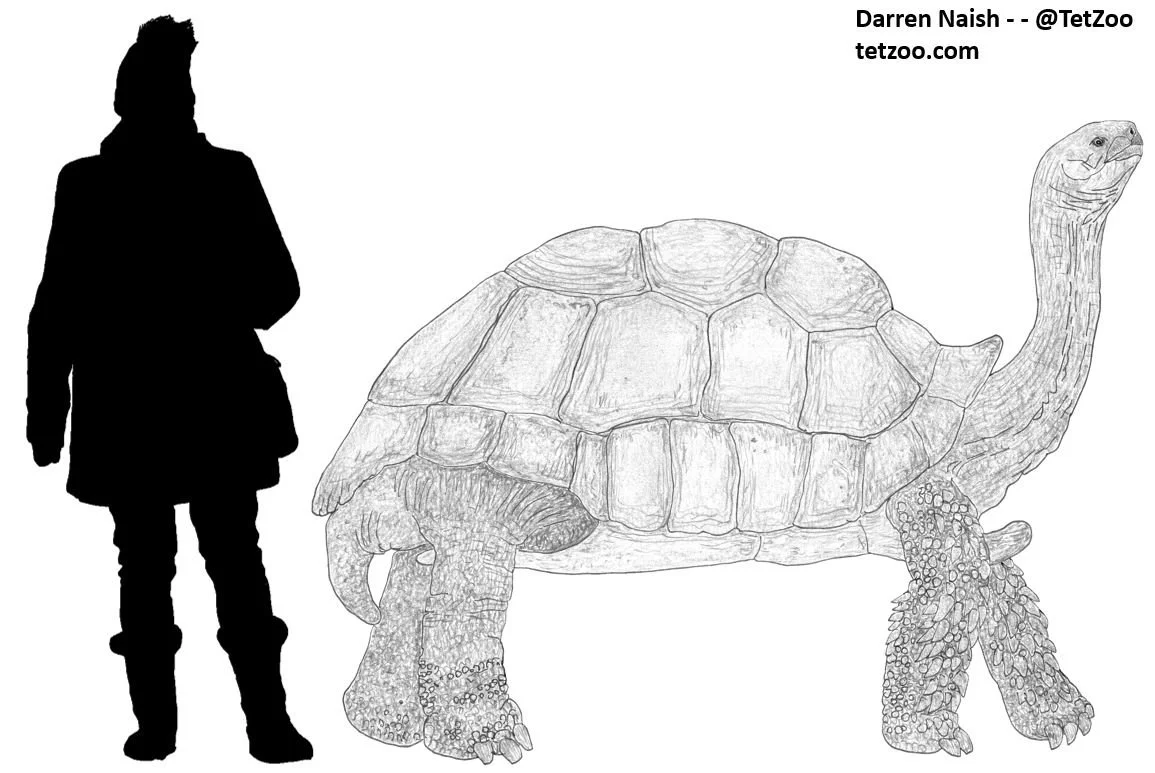

There are several Megalochelys species, and the biggest individuals of the biggest species (M. atlas) have a curved carapace length (CCL) of over 2 m and an estimated mass of over 900 kg. There are suggestions of even bigger individuals: Ren Hirayama and colleagues reported one from Myanmar with a carapace length of 2.7 m (Hirayama et al. 2015), though it's difficult to determine there if they were reporting straight-line carapace length or CCL, which makes a big difference. Whatever, Megalochelys was very big, and for an illustration produced in 2020 for my still in-prep giant textbook project… stops to sigh and peer out of the window for a few moments… I did a bit of research into working out what it might have looked like when alive. The text you’re reading here was previously published at the Tet Zoo Patreon but I’m recycling it here. Just think, you could have read this already, four years ago, if you supported me at patreon.

Caption: a familiar reconstruction of Megalochelys if you share a reading history at all similar to mine. This is Robert Bakker’s reconstruction from his 1986 The Dinosaur Heresies. The silhouette depicting Megalochelys might be somewhat oversized relative to the human and the modern giant tortoise… but then again, it might not given the size variation present in the three species depicted here. Image: (c) Robert Bakker.

Massive, forked epiplastra, scutes and thorn-like scales. An especially interesting feature of Megalochelys is that it has a massive, thick, robust, bilobed structure at the anterior end of the plaston, formed by the paired epiplastra (Falconer & Cautley 1837, Murchison 1868, Setiyabudi 2009, Srivastava & Schleich 2018). It’s about 15 cm thick (as in: deep in the vertical plane) in big adults, and we know from fossils of juveniles, subadults and young adults that it increased massively as maturity was achieved (Srivastava & Schleich 2018). When covered in its scutes (the gulars), this structure would have been even bigger. It’s narrow from side to side, allowing lots of room for forelimb movement, but is so similar to the forked epiplastra of some living tortoises (like Centrochelys) that it was surely used in similar fashion. That is, as a weapon during intraspecific combat.

Caption: the bifurcated, gently curved epiplastral fork or ploughshare of Megalochelys. At left, the reconstructed epiplastral fork of M. sivalensis, figured by Srivastava & Schleich (2018) and based on the holotype figured by Falconer & Cautley (1837). At right (the three photos labelled a, b, c), the same structure in (a) dorsal, (b) ventral and (c) right lateral views, this time belonging to a Megalochelys cf. sivalensis specimen from Java described by Setiyabudi (2009). The ploughshare is highly variable in precise size and shape, as is typical for structures that have a role in sexual combat.

The idea of two of these giants pushing and shoving with their ploughshare-like plastron edges is a compelling one that really needs depiction in palaeoart: I've seen one drawing which hints that it might be going on, but nothing really exciting or dynamic. So here’s a challenge to palaeoartists… can we get some thrilling, scary art depicting this behaviour birthed into existence, perhaps making the most of the size and determinedness of these tortoises and their lack of regard for the environment, adjacent foliage and maybe even unlucky nearby animals.

Caption: a long, bifurcated epipastral ‘ploughshare’ is present in various tortoises in addition to Megalochelys, and is used by them in shoving and fighting. African spurred tortoise or Sulcata tortoises Centrochelys sulcata – like the two shown here – do this, as do Madagascan Angonoka or Ploughshare tortoises Astrochelys yniphora. Image: a screengrab from Fred’s Reviews58 YouTube video here.

Some shells of these tortoises are well enough preserved that we can determine the position of their scutes (the scutes – some experts insist that they really should be called scales – do not align with the underlying bones of the shell), so I added those to my reconstruction after getting the form of the shell right. I then used the known limb bones to reconstruct the lengths of the limbs, and I deliberately gave the animal a relatively erect limb carriage where the legs are held in column-like fashion, this being based on the way the humeral heads fit into the scapulacoroid glenoid. At least some of the several Megalochelys species were continental animals, not island-dwellers... which led me to wonder if at least some of them might be especially well protected on the limbs, as are some big, continental tortoises of today (like Centrochelys). I added thorn-like scales and large, polygonal scales, and I think they look pretty good. The Megalochelys species might have been variable with respect to these details.

Caption: at left, a reconstructed Megalochelys carapace and plastron. Features to note include relatively large openings for the limbs and a highly domed shape. If you do plan to reconstruct this tortoise, be sure to view the shell from all angles, since it’s wide relative to its height. The scale bar is 10 cm. This specific specimen is from Flores and was reported by Setiyabudi (2016). Yes, these tortoises were on Flores during the Pleistocene, and hence lived alongside Komodo dragons, small stegodonts, giant storks and so on. At right, a life reconstruction that incorporates information from this specific shell. Images: Setiyabudi (2016); Darren Naish.

What else do we know? We have skull material for Megalochelys. Not only does this allow us to work out how large (or small) the head was relative to the rest of the animal (it was about similar in length to the humerus, so over 30 cm long in a very large individual), we also know that this was a tortoise with a short, deep snout and deep nasal region. In other words, the head was shaped much like that of the living Aldabran giant tortoises, so I used these animals as models for the look of the head shown in my reconstruction.

Caption: a Megalochelys specimen with a CCL (curved carapace length) of 2 m would look stupendous. Here I’m going to follow the long tradition of showing this animal to scale with a modern human: the one used here has a standing height (without hat) of 1.6 m. Image: Darren Naish.

There is, of course, a vast amount of additional stuff that could be said about this fascinating group of tortoises. And, yes, we should get into the habit of referring to them as a group rather than as a singular entity (given that there were several species). The good news is that Jura did a pretty good job of condensing information on them over at Reptilis.net back in 2016. That’s where we’ll end things for now, but I promise to return to turtles at some point in the near future.

For previous Tetrapod Zoology articles on tortoises and other turtles, see…

Gilbert White’s pet tortoise, and what is ‘grey literature’ anyway?, October 2008

Giant African softshells – wow!, Jan 2010

Giraffe-necked giant tortoises, May 2010

Giant fossil matamata turtles (matamatas part V), April 2011

In case you forget, softshell turtles are insanely weird, December 2011

Turtles that eat bone, rocks and soil, and turtles that mine, April 2014

Turtles I Have Recently Seen, June 2015

Letters from the World of Turtle Evolution, August 2017

Tortoises as Consumers of Carrion, March 2021

Tortoises as Consumers of Carrion, Part 2, June 2021

Leopard Tortoises, January 2022

Refs - -

Falconer, H. & Cautley, P. T. 1837. On additional fossil species of the Order Quadrumana from the Siwalik Hills. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 6, 354-360.

Murchison, C. D. 1868. Palaeontological Memoirs and Notes of the late Hugh Falconer: With a Biographical Sketch of the Author Compiled and Edited by Charles Murchison. Robert Hardwicke, London.

Setiyabudi, E. 2009. An Early Pleistocene giant tortoise (Reptilia; Testudines; Testudinidae) from the Bumiayu Area, Central Java, Indonesia. Journal of Fossil Research 42, 1-11.

Setiyabudi, E. 2016. Pleistocene reptiles of the Soa Basin (Flores, Indonesia): adaptation and implication for environment. Jurnal Geologi dan Sumberdaya Mineral 17, 107-124.

Srivastava, R. & Schleich, H. H. 2018. Fossil Turtles and Crocodiles from the Caenozoic of S Asia. Society for Amphibian and Reptile Conservation of Nepal, Munich.