It’s time to review the Migo once more…

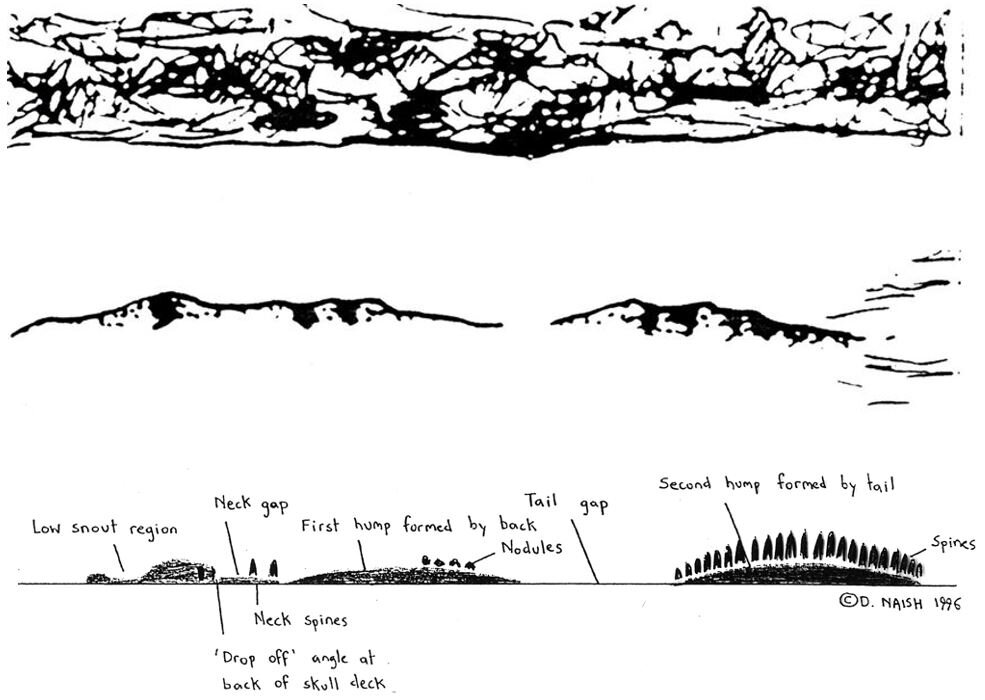

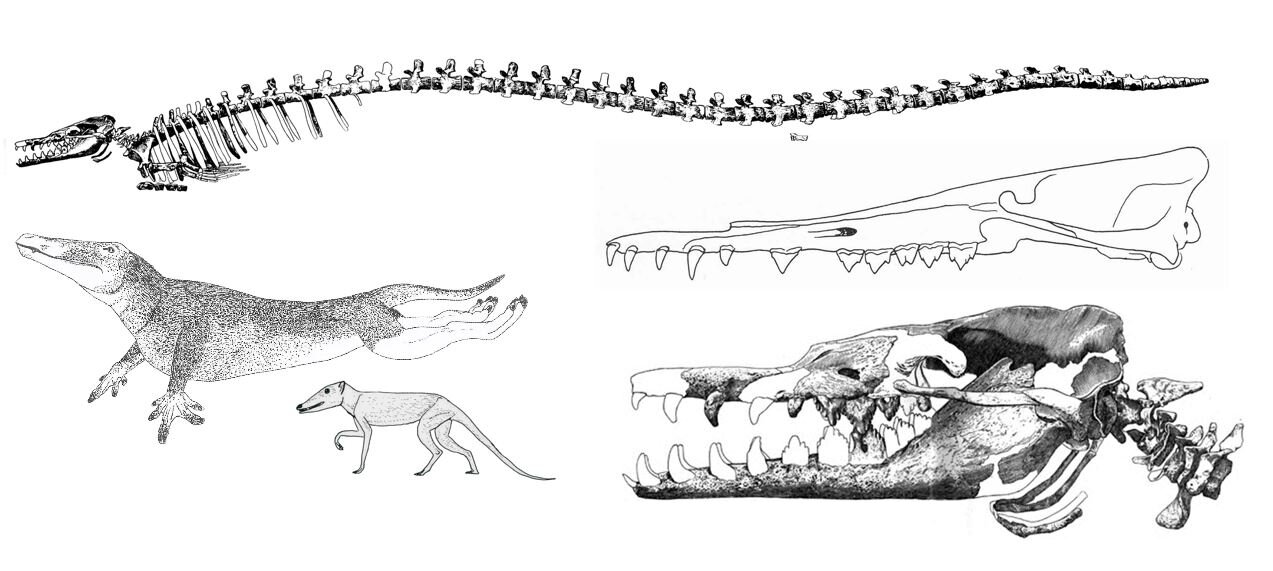

Caption: different schematic representation of the creature depicted in the Lake Dakataua footage of 1994. Images: at top, Lisa Peach/CFZ; below, Darren Naish.

As part of my TetZoocryptomegathread project on Twitter (in which I write about the backstory to a specific cryptozoological photo or bit of film), I recently decided to cover the Lake Dakataua ‘Migo’ monster footage of 1994. Long-time readers might recall me covering this at TetZoo back in 2008 (here’s the archived version of that article), but here it is again, this time with more detail and insight. The case of the Migo is complex. It involves crocodile systematics and behaviour, the ‘surviving archaeocete’ hypothesis, mosasaur life appearance as depicted in palaeoart, and the world of the pre-internet cryptozoological community. Let’s get started.

Caption: New Britain, largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago. Image: NordNordWest, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

What is the Migo? Also known as the Masali or Migaua, it’s an alleged mystery creature of New Britain’s Lake Dakataua, said to be about 4m long, and to be a flippered, long-tailed, long-snouted, aquatic, predatory animal. New Britain (Niu Briten in Tok Pisin) is the largest island in the Bismarck Archipelago, located to the north-east of New Guinea. It’s crescent-shaped, 520km long along its southern coastline, and volcanically active. Lake Dakataua is located at the northern end of the Willaumez Peninsula which projects from the island’s northern coastline. The lake is 76m above sea level, U-shaped, about 430m wide, 122m deep at its deepest, and highly alkaline.

Caption: the Willaumez Peninsula, location of our lake of interest. Image: Google Maps/Jimmy O’Donnell (original here).

The case of the Migo was, by 1994, already reasonably well known in the cryptozoological community, in part because ‘father of cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans included it in his influential and much-consulted 1986 checklist of mystery creatures awaiting discovery (Heuvelmans 1986). Heuvelmans’s list is fairly ridiculous and includes an enormous number of superstar creatures that – sorry, Bernard – surely aren’t real animals awaiting discovery, but that’s a story for another time. Anyway, therein, Heuvelmans lists the Migo as “an unknown species of crocodile (or is it, as has been suspected, a surviving mosasaur?)”. Yes, the supposed presence of an ‘unknown crocodile’ in Lake Dakataua had been kicking around since the 1950s…

The ‘New Britain upland crocodile’. The story (as known to westerners) essentially starts in 1956, when American herpetologist Wilfred T. Neill (best known for his 1971 book The Last of the Ruling Reptiles) published a brief paper in which he alluded to the presence of crocodiles on New Britain (Neil 1956). Neill had witnessed the crocodiles himself – “around the margins of upland lakes” – while flying over the island in a plane during WWII; he also mentioned a sighting made by another American serviceman (Neil 1956). Neill wasn’t sure what species they were, but they piqued his interest, and he suggested that they might either be New Guinea crocodiles Crocodylus novaeguineae or – more remotely – “an undescribed relative” of that species.

This determination makes – arguably! – the ‘New Britain upland crocodile’ a cryptid: an organism known from anecdotal evidence but not yet convincingly identified to species. If, however, you want to be argumentative, you could say that any such proposal is romantic, overtly speculative and, indeed, runs contrary to Occam’s razor, since it adds complexity to a less complex conclusion (namely, that the crocodiles that Neill saw were New Guinea crocodiles). An argument can also be made that Neill’s 1956 crocodile article (which didn’t even mention Lake Dakataua) has no connection at all with the events discussed in the remainder of this thread, but the literature is what it is. You’ll see what I mean.

Caption: New Guinea crocodile… I think (the remote possibility exists that this shows a Hall’s crocodile). Image: Midori, CC BY 3.0 (original here).

I should add the additional point of interest here that some of the crocodiles previously labelled ‘New Guinea crocodiles’ are now recognised as a second species: Hall’s crocodile C. halli, officially named in 2019 (Murray et al. 2019). Neill was actually among the first to suggest the existence of this distinct species and most sources which discuss New Guinea crocodiles have made reference to its possible validity. Whether it has any relevance to crocodiles on New Britain remains uncertain.

An alleged modern mosasaur. Fast forward to 1972, and a mysterious water creature on New Britain is again mentioned in the literature. This time, the venue was a Japanese newspaper article* (yes, newspaper article; remember that), and it’s significant in being the first recognised published source which used the name Migo and in claiming that local people knew of a “monstrous creature” that inhabited Lake Dakataua. This was said to be about 10m long, to have a crocodile-like tail, a neck which is “long and slim like that of a horse”, fangs, ‘flat’ ‘legs’ which recall those of a turtle (so… flippers?), and hair!

* ‘Many have seen big monster’, Mainichi Daily News, Feb’ 1st 1972.

According to the article, a Shohei Shirai of the Pacific Ocean Resources Research Institute had collected reports of the Migo from 15 local people. Shirai also learnt that the creature had been witnessed by a visiting German hunter, and even photographed by an Australian patrol officer. The article ended with Shirai’s suggestion that the Migo was perhaps a living mosasaur. Yes, a mosasaur – that group of mostly enormous aquatic lizards from the Cretaceous, which most assuredly went extinct about 66 million years ago. Until recently, mosasaurs have been portrayed as vaguely crocodile-like animals, traditional depictions showing them with a very gnarly, armour-plated surface and a wavy or serrated frill along the midline of the back and tail. Here’s one of those famous traditional illustrations, by great palaeoartist Charles Knight…

Caption: Charles Knight’s Tylosaurus, originally published in an 1899 article by H. F. Osborn. Image in public domain.

I reckon it’s that last feature – combined with the large size, monstrous nature and perhaps paddles too – which led Shirai to connect the Migo with mosasaurs. Not only is there no reason at all to think that mosasaurs survived beyond the end of the Cretaceous, there are, in addition, some notable anatomical issues here. It turns out that all those traditional reconstructions which show mosasaurs with a serrated or wavy dorsal frill are totally in error: there’s no reason at all to think that mosasaurs had such a thing. For one thing, mosasaurs are anguimorph lizards, part of the same major group as slow-worms, monitors, gila monsters and kin. No dorsal frills in this group.

Caption: the precise position of mosasaurs within Squamata is still debated (they may not be especially close to monitors and kin, as used to be widely thought). It is, however, largely agreed that they’re anguimorphs. The photos show (clockwise from upper left) the extant anguimorphs Anguis, Varanus and Heloderma. Images: Darren Naish.

Furthermore, fossil evidence contradicts it. The idea that mosasaurs might have a frill emerged following Samuel Williston’s 1898 claim that he’d found evidence for “a thick fringe or mane” on the animal’s dorsal midline (Williston 1898; see also Williston 1899). But he’d made a mistake: the segment of ‘fringe or mane’ actually represented misplaced cartilaginous rings from the trachea, a correction he made in 1902 (Williston 1902). All those 20th century artists depicting mosasaurs with frills (mostly influentially, Charles Knight and Zdeněk Burian) had been perpetuating an error.

In my 1997 Migo article (Naish 1997), I made a point of showcasing how out-of-date this ‘serrate-frilled’ view of mosasaurs was relative to more modern views – though it has to be said that my ‘new look’ mosasaur (‘b’ in the image here) now looks pretty dated itself. Cryptozoologist Richard Freeman said that it looked like “a penguin on acid”, which may or may not be a compliment. I might also note that Shirai’s mosasaur hypothesis ignores mentions of a long neck and hair, neither of which are mosasaur traits. Whatever… the main point of interest here is that all this stuff about the Migo being seen by multiple eyewitnesses, about it being a giant monster with a serrated tail and so on comes from a newspaper article.

Caption: a mosasaur montage from Naish (1997). (a) is a redrawing of a classic mosasaur image by the great Czech palaeoartist Zdeněk Burian; (b) was supposed to depict a mosasaur as they might actually have looked. It’s now quite dated in showing protruding teeth, a very cetacean-like colour scheme and a tail which lacks a vertical fluke. Hey, it was the ‘90s. Image: Darren Naish.

We’ve seen in previous evaluations of cryptids (see this TetZoo article on Cadborosaurus) that newspaper articles and the people who write them or get quoted in them become inadvertently lionised in the cryptozoological literature, as if they’re thoroughly trustworthy, factually affirmed sources. But, come on now, we’re talking about newspaper articles. They’re often not worth the paper they’re written on, sorry.

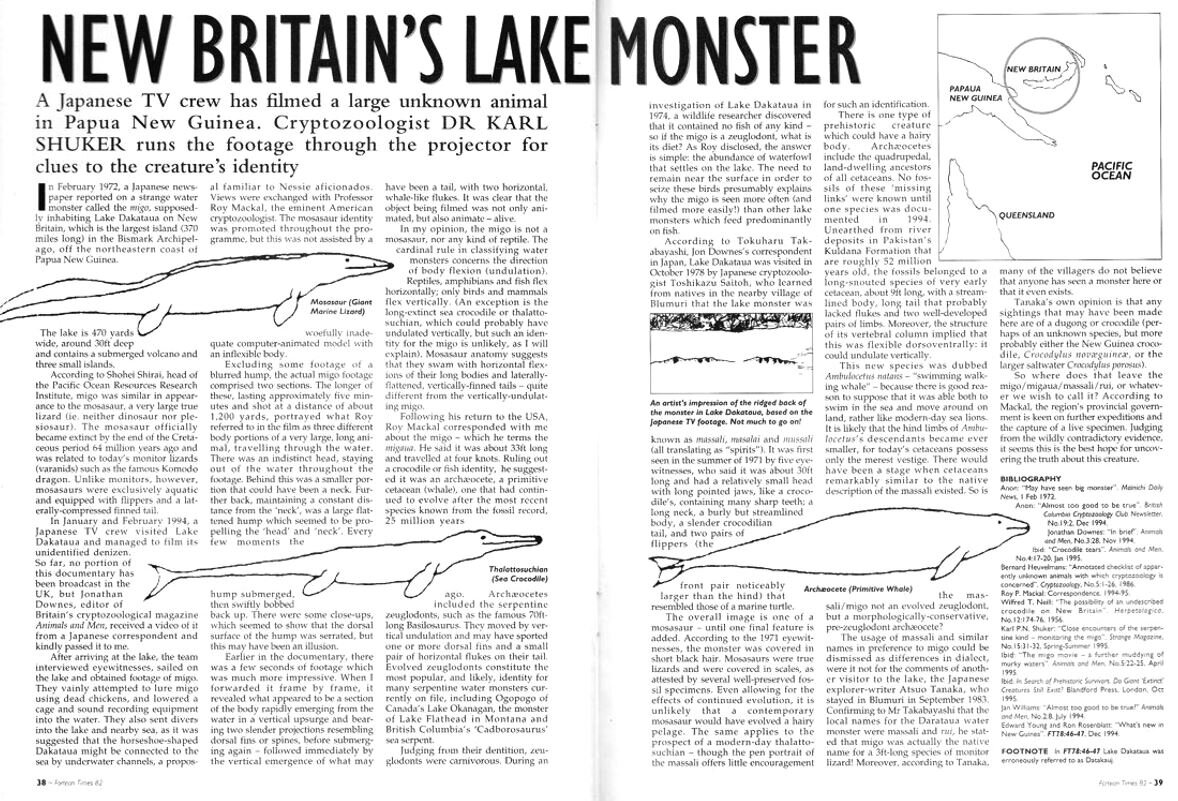

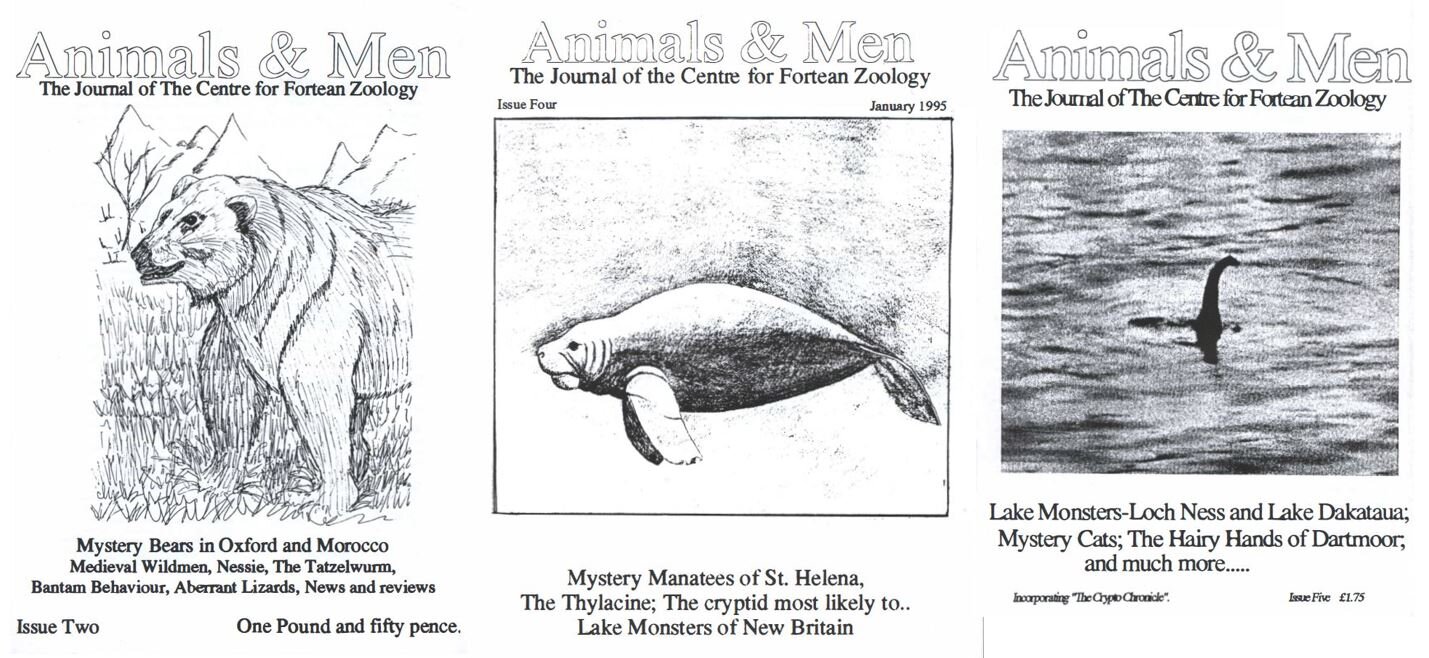

News of the 1990s. With all of the above as our canonical background, we now skip forward to June 1994 and the news – outed in the UK by author and leading cryptozoologist Karl Shuker at that year’s Fortean Times UnConvention meeting – that the Migo had been filmed! As published in cryptozoological magazine Animals & Men, Karl passed on information obtained from cryptozoologist Roy Mackal (who’s no longer with us; he died in 2013) that the creature had been filmed by a Japanese TV crew who’d travelled specially to Lake Dakataua in a deliberate effort to find it. Mackal had been on the same expedition and had seen the creature himself.

Excitement was high, especially because the footage was said to be surprisingly good. Alas, it had (at the time) only been broadcast in Japan. How might those of us elsewhere in the world hope to see it? Its existence became a regular talking point in discussions, and Animals & Men went through a period of several months whereby the editor (Jon Downes) would explain his exasperated efforts to get hold of it (Downes 1995a, b).

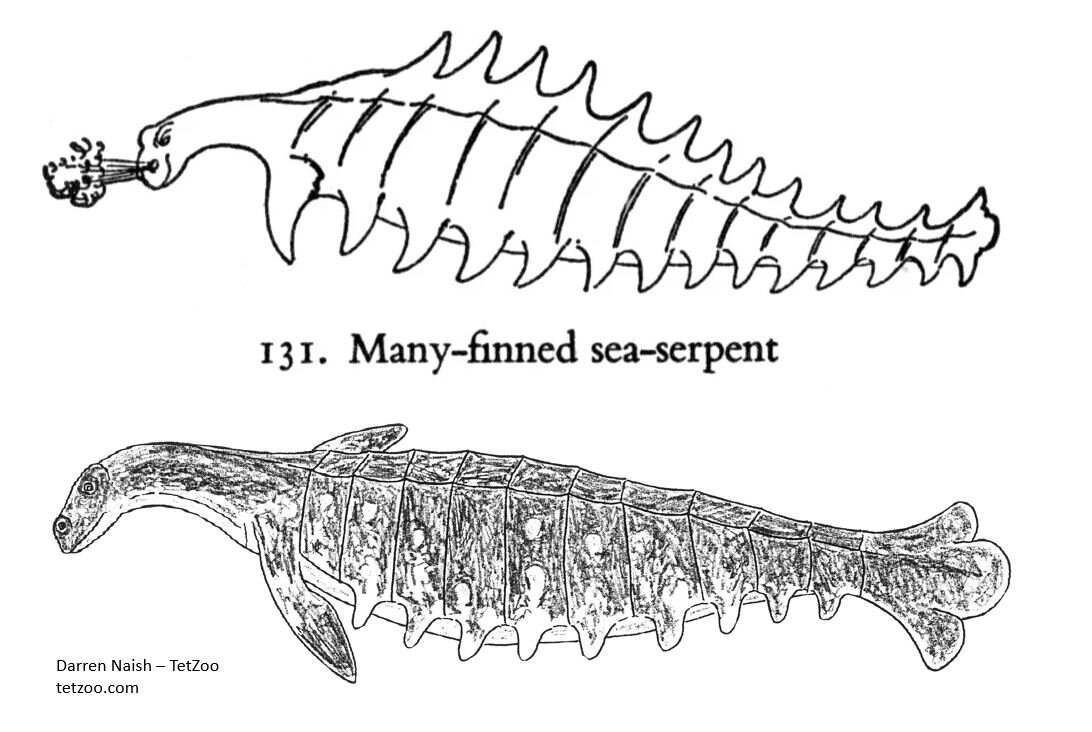

Caption: Cetioscolopendra, the great ‘cetacean centipede’ or ‘many-finned sea-serpent’ of Heuvelmans (1968), as depicted (at top) in In The Wake and (below) by myself.

Heuvelmans himself wrote to Jon. He’d heard that the creature moved by way of vertical undulations. If this was true, the creature must be a mammal, not a reptile. Perhaps, Heuvelmans noted in a letter (Downes 1995b), the Migo might be one and the same as the ‘many-finned sea serpent’, the existence of which Heuvelmans had postulated in his famous 1968 book In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents (Heuvelmans 1968). The ‘many-finned’ was, according to Heuvelmans, an armour-plated, post-Eocene basilosaurid whale, fringed along its edges by vertically mobile fins. I find it really interesting that Heuvelmans was still promoting the possible existence of this beast as recently as 1994 since – as explained in my books Cryptozoologicon Volume 1 (Conway et al. 2013) and the 2017 Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017) – its existence always was a bit of a joke and I can’t think that anyone was taking it seriously by the 1990s. Ulrich Magin’s deconstruction of Heuvelmans’s classification system for sea monsters was published in 1996 though (Magin 1996), so maybe Heuvelmans – as of 1994 – was still thinking that his ideas were good.

Caption: key critical works on the Heuvelmans sea monster scheme described in In the Wake: Naish’s 2017 Hunting Monsters and Ulrich Magin’s 1996 article in Fortean Studies 3, the latter still absent as a publicly accessible document.

In late 1994, the pages of the British Columbia Cryptozoology Club Newsletter (BCCCN from here) also covered the story of the Migo footage. They’d been sent a copy of the footage by veteran aquatic monster researcher Gary Mangiacopra, and had been able to watch the footage in the company of a Japanese speaker. The author of an editorial piece (I think written by the late Paul LeBlond, best known for his Cadborosaurus writings; see this relevant TetZoo article) explained how the TV show was broadcast on February 13th 1994 on Japan’s NHK network, that it definitely involved Lake Dakataua, and that the Japanese footage showed the team arriving at Port Moresby before flying to the Willaumez Peninsula on New Britain’s northern coast. The article further mentioned the involvement of Roy Mackal, noting in addition his (Mackal’s) preferred identification of the creature as…. a living archaeocete whale! We’ll come back to this proposal later.

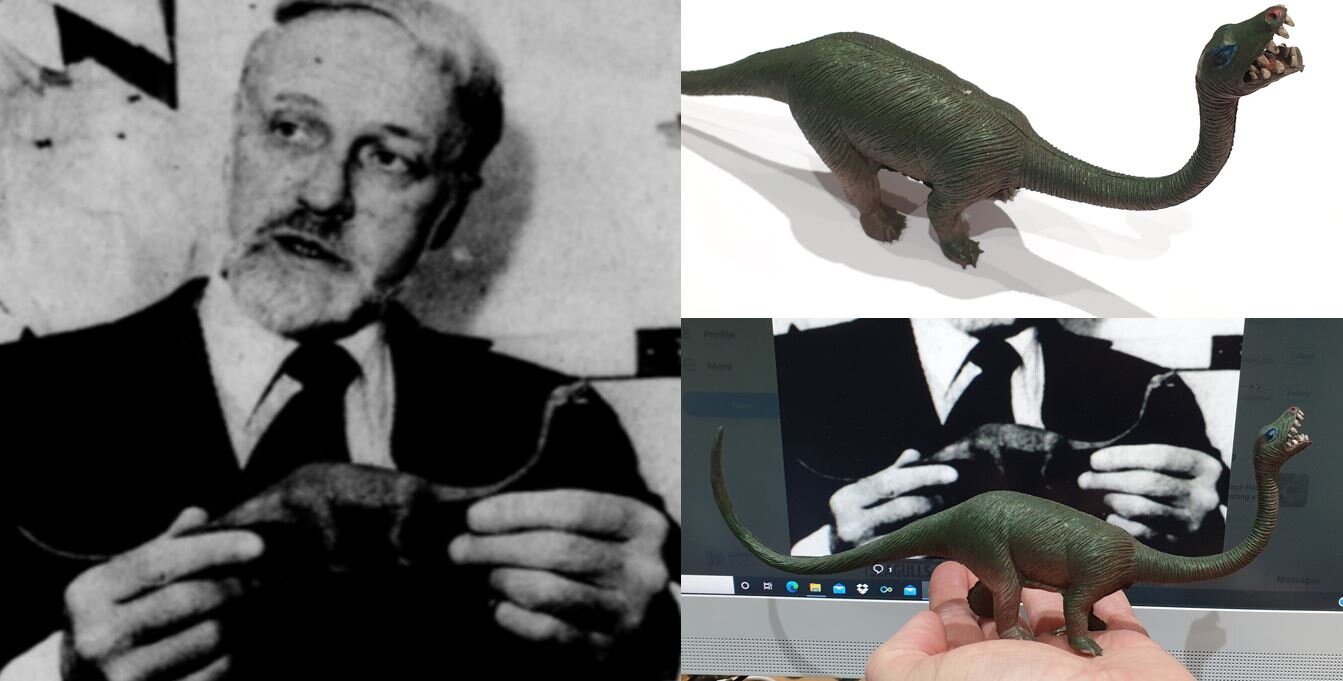

The BCCCN article also stated that the Japanese team were on-board with this archaeocete proposal and showed an animated model of it during the documentary. This isn’t right, actually. The Japanese team actually favoured the mosasaur identity we saw earlier, and the animated sequence showed a model mosasaur, not an archaeocete. Their mosasaur was pretty funny. It was very much a ‘traditional’ mosasaur of the sort described above (it was likely based directly on Knight’s or Burian’s art) and was shown swimming via an underwater tunnel into the lake. It was obvious that the model was expensive and technically quite a detailed creation, but it didn’t look great as a real animal. Jon described it in print as looking like a “clockwork newt”.

Caption: screenshots (literally, photos of the screen… ) of the mosasaur model from the Migo documentary. It was very obviously, I think, based on the artistic depictions of Charles Knight and/or Zdeněk Burian.

An oft-mentioned opinion on Lake Dakataua – repeated in all the articles discussed here – is that the lake lacks fish and other aquatic life, and that any big predator there can only make a living by catching wildfowl. A few sources state that the lake is of volcanic origin and highly alkaline, and that this has helped contribute to its lack of aquatic inhabitants. I don’t know how much of this is true (there are plenty of other geologically young, volcanic, alkaline lakes around the world which are inhabited by fishes and other animals), but it was, like I said, mentioned quite a lot.

Finally, a viewing of the footage. Would those of us in the UK ever get to see a piece of footage which, by now, was sounding like the holy grail of lake monster evidence? Well… as revealed in 1995’s issue of Animals & Men, Jon Downes in the UK had succeeded in obtaining a copy (on VHS tape) thanks to the kindness of correspondent Tokuharu Takabayashi. Jon wrote about the footage and what it showed in Animals & Men, his general conclusion being that it was exciting (more than the “unimpressive and amorphous blob” he was hoping it wouldn’t be) but difficult to interpret.

So he sent a copy to Karl Shuker, who published his thoughts on the footage in Animals & Men (Shuker 1995a) and also in the popular magazine Fortean Times (Shuker 1995b). Therein, Karl described the documentary footage as a whole before focusing on the Migo sequence in particular. He described the existence of two relevant sections, one showing a fast-moving animal which had two slender dorsal fins or spines, and another which showed a slow-moving animal with an indistinct head, and flattened dorsal hump bearing possible serrations. Sections of similar text were also included in Karl’s 1995 book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (a book more associated with the cryptozoological position known as the Prehistoric Survivor Paradigm, or PSP, than any other), but the book was in press (or, at least, had been submitted) by the time this news was breaking, and Karl was only able to include the Migo news as a ‘stop press’ section at the end of his chapter on water monsters (Shuker 1995c).

Karl’s take on the creature emerged from his combining his observations of the footage which those accounts from the 1970s mentioning crocodile-like jaws and alleged short fur. Perhaps, Karl proposed (here he was in agreement with Roy Mackal), the Migo was an archaic stem-whale similar to the four-limbed, terrestrially-capable forms of the Eocene, like the famous ‘walking whale’ Ambulocetus from Pakistan. Ambulocetus – described by Hans Thewissen and colleagues in 1994 (Thewissen et al. 1994) – was considered during the early 1990s to be part of a group of structurally primitive, long-extinct whales called protocetids, which are themselves part of a larger, more inclusive group called Archaeoceti.

Caption: at top, reconstructed skeleton of the Pakistani stem-whale Ambulocetus; below, reconstruction of Ambulocetus in a hypothetical swimming pose. Images: Notafly, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Darren Naish.

Neither protocetids nor archaeocetes are ‘natural groups’ (that is, clades: groups where all the members descend from the same single ancestor), since they appear to have been ancestral to later whale groups, the living ones included. They’re artificial groups recognised for convenience, or what’s technically known as paraphyletic. I should add that – in 1996 – Thewissen and his colleagues decided that Ambulocetus was ‘distinct enough’ from protocetids to get its own family (Ambulocetidae) (Thewissen et al. 1996), a decision since followed by other scientists specialising on archaeocetes.

The ‘surviving archaeocete hypothesis’. Whatever, the specific animals within these groups are universally thought to be long extinct: to have died out before the end of the Eocene, and thus to have been extinct for more than 34 million years. Yet archaeocetes display such a fantastic variety of anatomical configurations (check out the montage), and are so familiar as fossil mammals go, that they’ve often been cast as the potential ancestors of certain aquatic cryptids, something which may not be well known to the palaeontologists who study them.

Caption: an archaeocete montage, depicting something of the diversity present within the respective lineages (remember: Archaeoceti is a grade, not a clade. Some of these animals are much closer to crown-whales than others). Small and terrestrially capable animals are included, as are long-faced predators of vertebrates and long-bodied giants like the famous Basilosaurus.

In fact, archaeocetes like protocetids and the giant, long-bodied Basilosaurus are mainstays of the ‘prehistoric survivor’ literature, as familiar and oft-discussed as post-Cretaceous plesiosaurs. Where does this idea come from, and why has it persisted? Virtually a whole book could be written on the hypothesis of archaeocete survival. It started with the belief that Basilosaurus – the best known and earliest described of archaeocetes – was a veritable real-life ‘sea serpent’, a view promoted both by misinterpretations of its anatomy and by famed charlatan Alfred Koch’s fraudulent efforts to combine Basilosaurus skeletons in order to make the creature’s remains more impressive and more outlandish to paying spectators.

As noted by Hans Thewissen in his 2014 book The Walking Whales (Thewissen 2014), it was also partially driven by the fact that people’s views on the antiquity of archaeocete whales were vague: they knew that Basilosaurus was prehistoric, but not necessarily that it was more than 30 million years old. Ergo, long-bodied sea monsters seen off the coast of New England or wherever could still, perhaps, be living whales of this sort. I mentioned New England there because it was sightings made around the shores of that region which were, in particular, responsible for driving this ‘living archaeocete’ notion. As explored thoroughly in Robert France’s 2019 book Disentangled (France 2019), it today seems that the sightings concerned involved large animals (like tuna) seen pulling discarded fishing gear. I reviewed France’s book here.

Caption: covers of Heuvelmans (1968) - a key volume in the promotion of the ‘surviving archaeocete’ hypothesis - and Thewissen (2014), a volume which touches, ever so briefly, on the hypothesis (but doesn’t explore it in depth; it’s certainly not the focus of the book).

The result of all of this is that – from the late 1800s onwards – Basilosaurus would always be mentioned in discussions of sea serpents as if it might be a potential ancestor of such creatures. The great classic work on sea monster accounts of 1968 – Bernard Heuvelmans’s In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents (Heuvelmans 1968) – retained a promotion of the ‘archaeocete hypothesis’, but Heuvelmans did a very interesting thing.

Heuvelmans was a big proponent of the idea that cryptids might be the evolutionarily modified descendants of animals known only as fossils. Giving fair credit to intellectual input provided by his friend and colleague Ivan Sanderson, Heuvelmans described how various of the sea monsters outed in In the Wake were surely substantially modified, post-Eocene archaeocetes. Among these was the Super Otter, a huge, quadrupedal sea mammal which Heuvelmans imagined as a modern-day protocetid. Yes, I kid you not: an otter-shaped post-Eocene ‘protocetid’ the size of a rorqual. Heuvelmans’s writings are full of this sort of thing: he effectively made cryptozoology into speculative zoology, a fact I’ve emphasised in books (Conway et al. 2013, Naish 2017) and magazine articles (Naish 2014).

Caption: one of the several ‘surviving archaeocetes’ of Heuvelmans (1968) is the incredible SUPER-OTTER!

And thus protocetids now became folded into the pantheon of creatures considered part of the Prehistoric Survivor Paradigm too! The long, toothy jaws, amphibious lifestyle, quadrupedality and paddle-like (not fluked) tails of protocetids have in fact made them quite popular as potential cryptid prototypes. Here’s where we come back to the Migo.

Was Karl Shuker right in associating protocetids/ambulocetids with the Migo? There’s no indication at all that these animals survived beyond the Eocene: they’re truly archaic and should be ignored entirely when it comes to the evaluation of cryptid accounts. I think (and have said in numerous publications) that the PSP is woefully misguided and that there’s no reason to take it seriously. And, no, coelacanths don’t provide a precedent. Everything about them is utterly different from the tetrapods they’re so often compared to.

A brief interjection on Deinosuchus. Before we get to the Migo footage itself, I have to note one other identification proposed for the migo: namely, that published by Ronald Rosenblatt and Edward Young in Fortean Times in 1994 (Rosenblatt & Young 1994). They suggested that the Migo might be one and the same as Phobosuchus, an old name for the alligatoroid crocodylian Deinosuchus… yes, a giant fossil crocodylian from the Late Cretaceous of North America.

Caption: mounted Deinosuchus skeleton on show at Natural History Museum of Utah, Salt Lake City. Image: Daderot, CC0 (original here).

This is a classic case of the ‘clutching at straws’ widely present in the cryptozoological literature. Are there any features of the Migo at all which might link it with Deinosuchus? No. Young & Rosenblatt (1994) only mentioned that name because it was, most likely, the only big, crocodile-type prehistoric animal they were aware of (they thought that the filmed Migo was 30-40 ft long, which is dead wrong – more on this later). Their suggestion can, of course, be ignored.

The fabled footage. Fast forward to 1995… here’s where I need to discuss my own dealings with the footage. Thanks to the good graces of Jon Downes, I travelled to the Centre for Fortean Zoology in Exeter and was able to watch the footage at leisure. The copy Jon had been provided wasn’t great in quality, but it was good enough. We watched the whole of the documentary which includes the footage. As discussed earlier, it shows the Japanese team arriving (by plane) in the general vicinity of New Britain, and then making a short trek by boat.

Caption: at left, my schematic effort from Naish (1996, 1997) to depict the dolphins seen in the documentary footage. At right: a really awful screenshot, taken in the days before I could take screengrabs. Image: Darren Naish.

While in a boat, the team point out to sea as a group of dolphins swim past, three of which are seen breaking the surface. One dolphin emerges ahead of the other two, both of which appear as a single mass due to their proximity. Both roll and dive in step, their tails appear above the surface and we see the flukes of one of them. The whole sequence is shown, schematically, here, as is a very poor screenshot I was able to take. The dolphins are mostly seen in silhouette, but their profiles and proportions make me think that they’re Stenella dolphins, perhaps Spinner dolphins S. longirostris.

Caption: Spinner dolphins. Image: Alexander Vasenin, CC BY-SA 3.0.

In his 1995 articles on the case, Karl noted that a few seconds of the footage were “much more impressive” than the rest, since they showed “a section of the body emerging from the water in a vertical upsurge and bearing two slender projections resembling dorsal fins or spines before submerging again – followed immediately by the vertical emergence of what may have been a tail, with two horizontal, whale-like flukes” (Shuker 1995a, p. 38). The implication from Karl’s writing is not just that this segment shows the Migo, but also that it provides support for the idea that the Migo is a cetacean, and a living archaeocete.

Jon and I phoned Karl as we watched the footage and, with his help, confirmed that the dolphin sequence described above was indeed one and the same as the piece of footage he had in mind. Seeing as it was filmed at sea, and seeing as it obviously showed dolphins, it was, alas, irrelevant to the creature filmed in the lake, and indeed to the Migo case as a whole. To be fair, I should note that the version of the footage which Karl obtained (a second generation copy) was of poor quality; to quote Jon “my video duplicating equipment was primitive in the extreme, and he was unlucky to get a copy somewhat akin in quality to one of the ‘bootleg’ copies of Disney movies which one can purchase at car boot sales. It has to be stressed that my equipment even managed to miss out bits of the documentary”. Basically, I had access to a much better copy (a first generation copy, no less) of the documentary than Karl did.

Caption: still from the Migo footage, artificially darkened to increase contrast.

What of the Migo footage itself? It’s no fleeting glimpse but is around 5 minutes long and clearly shows a large, dark animal swimming, from right to left, across the surface of the lake. Unfortunately, it was obviously very far from the camera, and the footage is extremely blurry and pixelated, I think because the camera operator was filming at maximum zoom. The consequence is that all edges are jagged and staircase-like, that parts of the animal’s outline (and any surrounding dark areas) merge into one another at times, and that the animal is not all that distinct relative to the water surface. You can see what I mean from the adjacent screenshots.

Caption: more stills from the footage. Note the tall posterior section to the back of the head, long and low thorax and dorsally serrated tail.

We do, however, see quite a lot of anatomical detail. Even by late 1996, this hadn’t been conveyed by any of the writers who’d covered the Migo so far, so – in the Autumn of 1996 – I published an initial paper in The Cryptozoology Review wherein I described the footage (and the creature it shows) in reasonable detail (Naish 1996). Back in those days, I had no access to any digital processing software or technology of ANY sort (I didn’t even own a home computer), so any interpretation of an image viewed on a screen (in this case, a TV screen, not a computer monitor) had to be done on paper… and, partly as a consequence, my interpretation was quite off in its proportions.

Anyway, as you can see, we see a longish, low snout, close to the water, followed posteriorly by a taller, box-shaped head section. There’s a dark vertical marking at the back of the ‘box’. There’s then a gap between the back of the head and the low hump formed by the animal’s torso. This corresponds to the neck, so I call it the ‘neck gap’. In some parts of the footage, the ‘neck gap’ is totally empty and there’s only water there, but in other parts, two vertical spikes or spines are present in the gap. There’s then the long, low torso, decorated on its upper surface by a series of low nodules (these appear and disappear during the sequence), then another gap. That last gap – it separates the torso from the tail – is fairly long, and I’d erred in my 1996 illustration by making it too short. I aimed to correct it in another illustration, published in 1997 (Naish 1997).

Caption: additional efforts to depict the animal shown in the Lake Dakataua footage, the upper of which was published in Naish (1996, 1997).

Finally, there’s a long tail. It clearly has a serrated dorsal surface and around 8 vertical spines are visible along its length. These fluctuate in number during the footage, and something like 10 might be visible on occasion, it’s hard to say. I’d definitely overdone it and drawn too many in my 1996 and 1997 illustrations. The tail is clearly mobile and disappears and reappears during the footage. I – and others – initially thought that this was indicative of vertical movement of the tail, something more consistent with a mammalian identification than a reptilian one, but… remember what I said about the footage being filmed at maximum zoom, and of being highly pixelated? This supposed ‘vertical movement’ is just due to the fact that the tail’s pixelated look means that it ‘jumps’ relative to the water surface, either because ripples make contact with it or because of distortion. We’ll come back to the ripples and the tail movement in a moment.

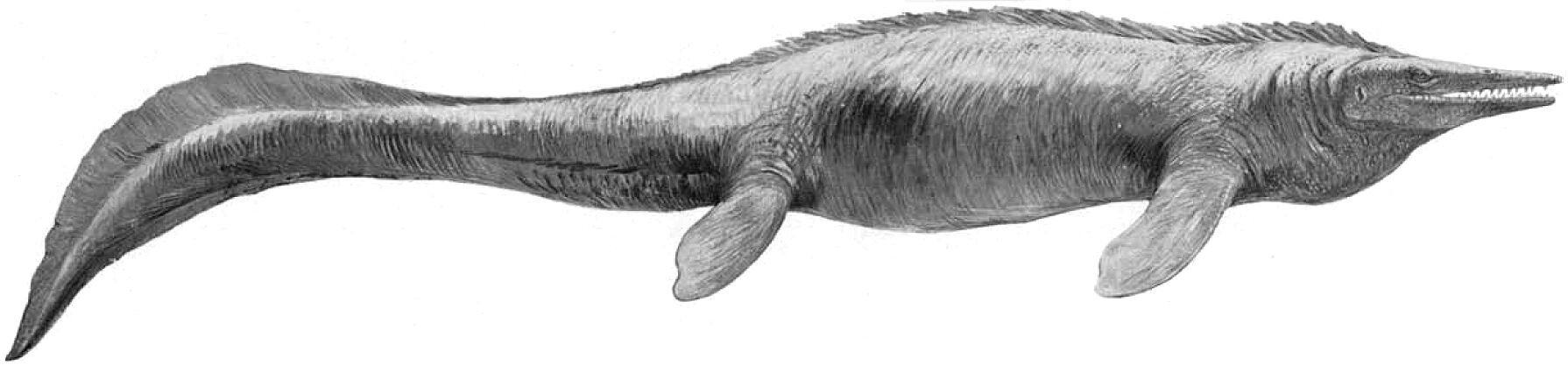

So, what do we have? A long-snouted, swimming animal with a raised posterior section on its head, a low thorax marked with nodules of some sort, and a sculling tail lined with vertical serrations. I decided to have some fun and interpret it as the ‘evolved archaeocete’ hinted at by Mackal and Shuker, and here’s the result.

Caption: the animal in the footage as a purely hypothetical post-Eocene protocetid. Don’t take this image seriously. Image: Darren Naish.

What a croc. But, in reality, it can only be one thing, and that one thing is, of course, a crocodile. In fact, it’s obvious that this is what it is. We can’t be 100% sure what crocodile species it is but it’s sensible and reasonable to assume that it’s a Saltwater or Indopacific crocodile C. porosus. Not only is New Britain well within the geographical range of this species (I produced the rather primitive map shown below), the species – despite its name – frequents freshwater environments as well as estuarine and marine ones. The anatomy is also right for this species: those two vertical spines in the ‘neck gap’ are in the right approximate position for the two cervical osteoderms present in this species (osteoderm distribution is diagnostic among crocodile species and differs from one to the next).

Caption: simplified map depicting the approximate range of the Saltwater crocodile, from Naish (1997). The stars show extralimital records.

Could it be a New Guinea crocodile, as per W. T. Neill’s suggestion from the 1950s? It’s possible, but there’s one anatomical detail which counts against such an identification. Recall that the animal in the Migo footage has prominent vertical ‘spines’ in its ‘neck gap’? These correspond quite well to the tall and prominent, posteriorly located cervical scutes of the Saltwater croc. The New Guinea croc has those scutes too, but they’re lower and much less obvious.

Caption: New Guinea and Saltwater crocs differ obviously in cervical scute arrangement and anatomy. Images: Midori, CC BY 3.0 (original here), Darren Naish.

I should also mention the animal’s size at this point. Roy Mackal had said of the Migo footage that the animal was perhaps 10 m (33ft) long, but a very rough comparison with the wildfowl present in the footage shows that this is too high. It’s almost certainly not even 6m (18ft) long.

Anyway, I was sufficiently confident about the crocodile identification that – in 1997 – I published my definitive article on the Lake Dakataua footage, titled ‘The Migo is (probably) a Crocodile’ (Naish 1997). Today, I regret including the disclaimer but, hey, I was young. Anyway… case closed: the footage shows a lone Saltwater crocodile. My article on this conclusion appeared in a, err, somewhat obscure (and phenomenally esoteric) publication; namely, The Centre for Fortean Zoology Yearbook 1997 (Naish 1997). Back in those days, I wasn’t working at all hard to get cryptozoological articles into ‘mainstream’ technical journals (my early publishing efforts involved a lot of bad and/or poor decisions). Today I know that it could have totally gone somewhere better.

Caption: the venues for my Migo articles. The CFZ Yearbook volumes are mighty esoteric and contain so much weird content (the image on the cover is from one of de Sarre’s initial bipedalism articles)… pretty awesome if you like that sort of thing.

Anyway, because the Migo and the Japanese footage were pretty hot news at the time, my conclusions were considered interesting within the broader community of people investigating weird news, mystery creatures and so on, and thus it was that – in the December of 1996 – I was asked to give a talk on the footage at the Fortean Times annual convention – dubbed UnConvention, ha ha – during April 1997. I have fond memories of giving that talk and indeed of the whole event, it was good fun. My talk went alright, even though it hadn’t been realised that I’d need AV equipment in addition to a VCR and projector. I spoke about the background to the case – pausing every so often to climb off the stage and walk over to the overhead projector before climbing back onto the stage – before finally showing the footage. There was an audible gasp of… some undefined emotion when the dolphin footage was shown, but of course the main event was the showing of the Lake Dakataua footage itself.

There was substantial media interest in my talk and conclusions; I was interviewed by numerous journalists and several news pieces on UnCon as a whole mentioned my Migo talk as one of the highlights. Incidentally, the full title of the talk was ‘What a croc: a new look at New Britain’s migo, the lake monster’. A commercially available recording was made and I still have it on cassette.

Caption: an UnConvention97 montage, featuring excerpts from newspaper pieces in The Express and The Sunday Telegraph. The journos of the day were mostly interested in Richard Wiseman’s take on the Indian rope trick, Jon Downes’s talk on ‘The Phantom Wallaby Slasher of Newquay Zoo’ and Duncan Lunan’s presentation on the green children of Woolpit… but the Migo at least got an occasional mention.

Two things worthy of note happened next. The first is that at least a few people in the cryptozoological community remained unaware of, or chose to ignore, my conclusions. For all his musings on the Migo being a modern-day archaeocete, Roy Mackal, at some point, changed his mind, and now regarded the creature of interest as a crocodile. I should note here that Karl Shuker is also now an advocate of a crocodylian identity for the creature. Yet Mackal now kept on telling people that the footage showed two crocodiles engaged in the act of mating. Partly because Mackal was (and is) respected within the cryptozoological research community, this conclusion became repeated a lot, more so than my own conclusions.

Mackal’s mating Migo. As explained by Karl in his own recently published review of the Migo case (the fact that we’ve both covered the Migo at about the same point in time is, incidentally, entirely coincidental), Mackal’s views were based on a second sighting, which was also filmed (the relevant footage is as yet unreleased and remains unseen by any of the other people mentioned in this article). This second sighting (made by Mackal himself) involved three animals, identified as two males pursuing a “female in heat” (I’m quoting Mackal himself there… crocodiles assuredly do not go ‘into heat’!). Apparently, all three formed a gigantic composite beast, 50 ft long.

Here’s the thing though. Be that as it may, I simply don’t think it’s relevant to the first piece of footage (which Mackal also got to watch with his own eyes). As you can see from the images I’ve used throughout this article, it unequivocally does not show two or more crocodiles in the act of mating, or in any act at all, actually. It very clearly shows a single crocodile, swimming right to left across the screen.

Caption: one of the relatively few images of Roy Mackal available online. I think I might have identified the toy dinosaur he’s holding. If I’m right, that’s… that’s not exactly the best toy to be using as a prop, Roy.

Incidentally, Mackal also said at one point that the procuring of footage which showed mating behaviour in the Saltwater crocodile was a big deal, since this – supposedly – hadn’t been filmed before. But this isn’t correct; there are various published works from the 1990s and before which show mating in this species.

I remain sceptical of Mackal’s ‘we saw them mating’ claim. Crocodiles are complex animals, and what he described isn’t necessarily implausible, but it doesn’t match other data on sexual behaviour in Saltwater crocs. Males, for example, are highly competitive: there’s a lot of action above the water when they’re in close vicinity, often including fighting. But, whatever – the point is moot seeing as I haven’t seen the footage he had in mind. Karl also shared news that Mackal was planning to write a scientific report on the whole Migo saga for the International Society of Cryptozoology’s journal Cryptozoology, but that never happened (the society folded, for reasons).

Caption: it was a croc all along. Image: Darren Naish.

Not a fake or a hoax. During my UnCon talk, I drew attention to the supposedly problematic vertical movement of the crocodile’s tail in the original Migo footage, and to the presence of those supposedly problematic ripples. As noted earlier, I don’t think that these things are at all problematic today, but, back then, I did.

In the Q&A after my talk, an audience member (specifically, a regular on the mystery animal circuit named Mike Grayson) put it to me that he had a potential explanation. Could it be, Mike said, that this was a dead crocodile, that it was being pulled along by a boat, that its vertical motion was due to its deceased condition (it was limp in the water and not swimming at all), and that the ripples were due to disturbance from said boat? Now, dealing with this proposal was tricky, since agreement (in a public forum, which was being recorded for posterity and due to be reported in venues worldwide) would mean accusing the Japanese team of outright fakery (or, at the least, of being duped by fakery). I didn’t want to do this without gaining more information, so essentially said on the day that, while it was an interesting idea, I couldn’t comment further. Author and historian Mike Dash, who was chairing the session, asked in closing when I’d be prepared to make clearer statements about this potential of it being some sort of hoax. I replied, “When I have a legal representative”, which at least got a good laugh from the crowd.

To be clear, I no longer think that any such charges need making. Repeated viewing on larger screens than those available at the CFZ revealed that the vertical movement of the tail is an artifact and not an especially big deal, and… yes, there are what look like ripples moving across the water (at times interacting with the crocodile), but there’s no reason to be suspicious about them. If they are ripples, they might result from the take-off of the various waterfowl (of unidentifiable species) also visible in the footage.

In 1997, researcher Nick Molloy published an article (also in Animals & Men) in which he mostly agreed with my evaluation of the footage, and in which he also commented on claims of the footage being hoaxed (Molloy 1997). He essentially didn’t see any evidence for this, and he also argued that the supposed ‘ripples’ were so hard to interpret that they might actually be the result of heat haze or the result of digital distortion of some sort. I’m happy to agree with this, and indeed I don’t think that there’s anything suspicious going on here…

Caption: part of this article feels something like a love-letter to Animals & Men, the most exciting cryptozoology-themed publication of the 1990s. Here are covers of the issues which charted the developing Migo story.

What should always have been a red flag for the ‘towed by a boat’ hypothesis is that the footage ends with the crocodile swimming perpendicularly away from the camera until it disappears from the surface. In other words, it submerges. I’m sure one can devise a method by which any and all of this could be faked, but it would involve something of pretty sophisticated complexity, and the whole idea is substantially less simple than the idea that we might simply be witnessing a wild, living crocodile swimming across a lake.

What has happened in the world of Migo research since those busy days of the mid-1990s? Well, nothing really, so far as I can tell. Claims that Lake Dakataua might really be home to a ‘modern archaeocete’, or that one was captured on film in 1994, haven’t really persisted in the literature. There aren’t desperately romantic, argumentative and spiteful ‘Migo truthers’ as there are for Nessie or Mokele-Mbembe.

Caption: proof that the Migo story was covered at TetZoo before (back in 2008)….

As mentioned earlier in this thread, my take on this case was written up for TetZoo back in 2008. That article is here (I have to link to a wayback machine version as the ScienceBlogs original has been ruined by its hosters).

And that about brings the whole saga to a close. I mentioned earlier that the early and mid-1990s did seem (to some of us!) like an extremely optimistic time for scientific cryptozoology, and (from my perspective) the claim that a bona fide tropical lake monster had been definitively captured on film was all part of this optimism. Alas, it was not to be…

For previous TetZoo articles on aquatic monsters and connected issues of cryptozoology, see…

Book Review: Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, November 2014

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent, November 2019

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, October 2020

The Case of the Cadborosaurus Carcass: a Review, November 2020

Morgawr and the Mary F Photos, February 2021

Refs - -

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume 1. Irregular Books.

Downes, J. 1995a. Crocodile tears: what IS happening in THAT lake with THAT video? The editor aims to find out and fails miserably.. Animals and Men 4, 17-20.

Downes, J. 1995b. Crocodile tears II. Animals and Men 5, 22.

Heuvelmans, B. 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Heuvelmans, B. 1986. Annotated checklist of apparently unknown animals with which cryptozoology is concerned. Cryptozoology 5, 1-26.

Magin, U. 1996. St George without a dragon: Bernard Heuvelmans and the sea serpent. In Moore, S. (ed) Fortean Studies Volume 3. John Brown Publishing (London), pp. 223-234.

Molloy, N. 1997. The migo – not yet explained? Animals & Men 15, 31-34.

Murray, C. M., Russo, P., Zorrilla, A. & McMahan, C. D. 2019. Divergent morphology among populations of the New Guinea crocodile, Crocodylus novaeguineae (Schmidt, 1928): diagnosis of an independent lineage and description of a new species. Copeia 107, 517-523.

Naish, D. 1997. The migo is (probably) a crocodile. In Downes, J. (ed) The CFZ Yearbook 1997. CFZ (Exeter), pp. 51-67.

Naish, D. 2014. Speculative zoology. Fortean Times 316, 52-53.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters. Arcturus, London.

Neill, W. T. 1956. The possibility of an undescribed crocodile on New Britain. Herpetologica 12, 174-176.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1995a. The migo movie: a further muddying of murky waters. Animals and Men 5, 22-25.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1995b. New Britain’s lake monster. Fortean Times 82, 38-39.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1995c. In Search of Prehistoric Survivors. Blandford, London.

Thewissen, J. G. M., Hussain, S. T. & Arif, M. 1994. Fossil evidence for the origin of aquatic locomotion in archaeocete whales. Science 263, 210-212.

Thewissen, J. G. M., Madar, S. I. & Hussain, S. T. 1996. Ambulocetus natans, an Eocene cetacean (Mammalia) from Pakistan. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 191, 1-86.

Williston, S. W. 1898. Editorial notes. Kansas University Quarterly 7 (4), 235.

Williston, S. W. 1899. Some additional characters of the mosasaurs. Kansas University Quarterly 8, 39-41.

Williston, S. 1902. Notes on some new or little-known extinct reptiles. Kansas University Science Bulletin 1, 247-254.

Young, E. & Rosenblatt, R. 1994. What’s new in New Guinea? Fortean Times 78, 46-47.