It’s a Fact that everyone loves stories about sea monster carcasses…

Caption: one of several good photos showing the so-called Moore’s Beach monster. The body was obviously heavily distorted, collapsed and perhaps desiccated but the head was very much intact. These pictures have been widely shared online and I’m not sure who should be properly credited.

Back in 2008 (at TetZoo ver 2, the ScienceBlogs years) I did a whole week of articles on sea monster carcasses. You can’t easily find or see any of that stuff today (though it is still findable via wayback machine), since it was all ruined after ScienceBlogs went down the pan. Tons of my stuff has been affected by this, it’s frustrating. Anyway… for no particular reason I thought I’d re-vamp and republish one of those articles today, specifically the one on the beached ‘monster’ carcass that washed ashore at Moore’s Beach – today known as Natural Bridges State Beach – just north-west of Santa Cruz, California, in 1925. While identified correctly in virtually all of the cryptozoological literature I’ve seen, this carcass is still identified here and there on the internet (particularly on pro-creationism sites) as an unidentified anomaly that had the experts baffled. Below, the text is slightly augmented and modified, but not much. You can see the original article here. It also incorporates text originally published as a second article, titled Skull of the Moore's Beach Monster Revealed! and available here.

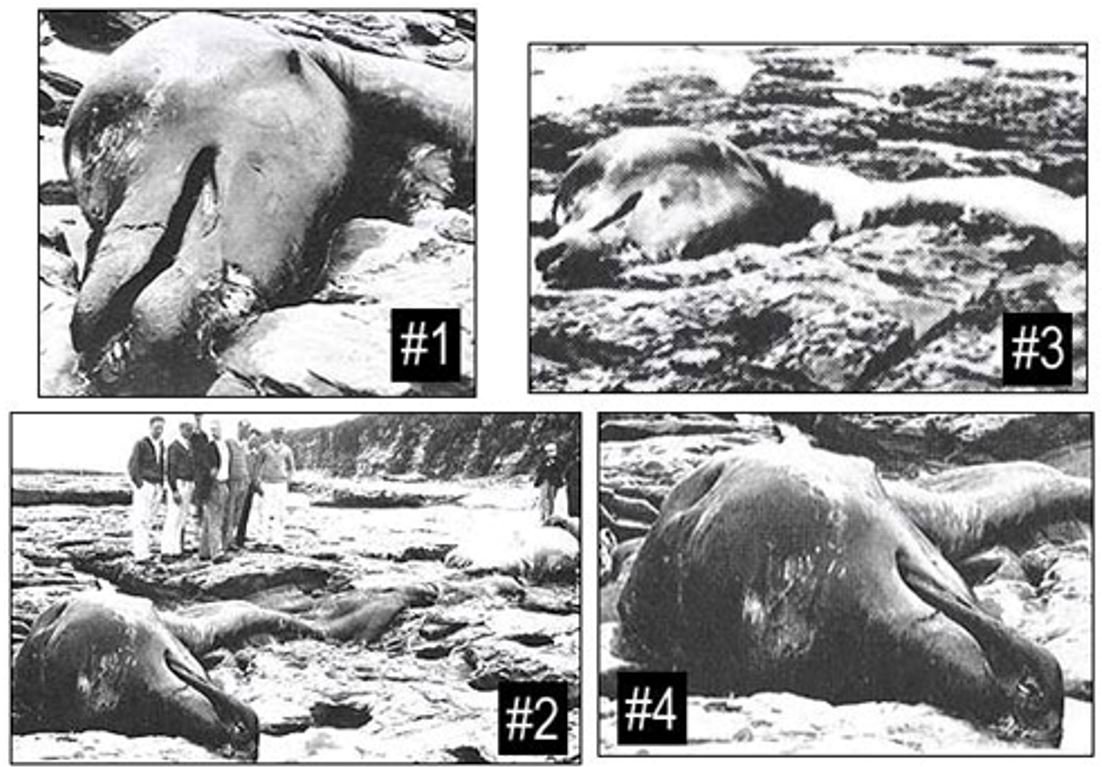

Caption: a montage of images showing, variously, the head (in oblique left lateral [#1] and oblique dorsal [#4] views), the head and anterior part of the body in left lateral view [#3] and that landscape image again [#2]. This image was taken from a 'creation science' page here where it was credited to Special Collections, University of California at Santa Cruz

The real identity of the carcass – usually dubbed the Moore’s Beach monster (sometimes the Santa Cruz monster) – is obvious and you’d have to be a less than competent researcher to not work it out…

What seems to have confused people is that the body and tail formed a 6-m-long, tubular shape, thereby creating the impression of a super-long neck. According to some accounts the whole carcass was 15 m long but, based on the photos, this measurement is very likely an exaggeration. What’s also not helped is that some authors (writing either in newspapers or in books on ‘unexplained mysteries’) reported the presence of elephantine legs on the carcass, complete with toenails (Chorvinsky 1995). It’s difficult to understand from the photos where these ‘legs’ might have been and they clearly aren’t visible in the photos. Some reports referred to a fish-like tail.

Caption: I get the impression that not everyone realised or realises that the head’s upper surface is to the left of this image, rather than the right. Note the massively bulbous forehead and the damage to the snout and jaw tips. This damage indicates that the carcass had been exposed on the rocky pavement here for some while (weeks, at least).

Most importantly, the head was very much intact and is perfectly displayed in photos. The eyes are small, the forehead bulbous, and the jaws form a vaguely duck-like ‘beak’. These photos show, without any doubt, that the carcass is of a decomposed Baird’s beaked whale, or Baird’s fourtooth whale Berardius bairdii. Repeated in most texts is the fact that this identification was provided by the California Academy of Sciences, which makes me wonder if a technical paper ever appeared on the specimen*. CAS collected the skull and added it to their collection, and today it’s on display at the Academy’s Cowell Hall (read on…).

* McLellan Davidson (1929) published a brief report noting identification of the specimen as B. bairdii.

Caption: the sharpest and most detailed image of the carcass I’ve seen. I don’t recall seeing it online back when I first wrote about this case in 2008.

Baird’s fourtooth is the largest extant beaked whale: a Californian example stranded in 1904, and another one caught near Japan and described in 1971, were both about 12.8 m long (Balcomb 1989), but 10-11 m is considered average. It has weird teeth, a weird social life, and a weird stomach, and for more information look at Cameron McCormick’s article on the two fourtooth whales here (well, the two known at the time of writing, read on…).

One article on the internet (by Jordan Niednagel at Creation Science Evangelism) claims that, while the carcass is indeed of a cetacean, its identification as Baird’s fourtooth doesn’t wash because, while B. bairdii has a pair of triangular teeth at the front of the lower jaw, followed by a smaller peg-like pair located somewhat further back, the Moore’s Beach monster lacks obvious teeth and only has a few ambiguous white patches at the very tip of the lower jaw. The author of this article must not have looked at many photos of Baird’s beaked whales, however, because these show that – particularly in juvenile individuals and in old individuals with heavily worn teeth – the posterior tooth pair are often virtually invisible (apparently because they’re submerged in gum tissue) while the anterior pair can be so small that they appear only as small white specks (Balcomb 1989, fig. 5). Look at the image below; I’ve inserted the huge arrow to show how inconspicuous the anterior teeth are in an undoubted B. bairdii carcass. What we see in the Moore’s Beach carcass is entirely consistent with this. Incidentally, the jaws of the Moore’s Beach carcass look shorter than those on the partially defleshed skull shown below because, well, the skull below is partially defleshed. Cetacean skulls always look longer-jawed than do live animals because a huge amount of soft tissue envelops the base of the rostrum in the live animals.

Caption: the partially defleshed head of a Berardius that washed up on California’s Ocean Beach in (I think) 2007, here being prepared by Ray Bandar. The image reveals the protruding lower jaw and its anteriorly placed teeth. Image: Jack Bumbacher of CAS, original here.

One particularly unusual identification of the carcass, apparently coming from a respectable source, is often mentioned as it also seems to cast doubt on the B. bairdii identification. Apparently, E. L. Wallace concluded that it couldn’t be a whale and might be a plesiosaur that had been preserved in glacial ice (Reinsted 1975, Chorvinsky 1995). Wallace thought that the neck-like part of the carcass really was a long neck, that the bones he could find were too small to be whale vertebrae, and that the bill indicated a herbivorous diet. He is quoted as having said “I would call it a type of plesiosaurus”. Wallace has been referred to as a ‘renowned naturalist’ and as someone who had twice served as president of the Natural History Society of British Columbia, but I don’t know anything about him, nor have I heard his name mentioned outside of the literature on the Moore’s Beach monster. I cannot congratulate him on his knowledge of whales, plesiosaurs, or of rotting carcasses.

Rotting whales that have been identified from elsewhere in the world show us that floating carcasses can drop their bones and eventually look like amorphous, misshapen lumps of goo (often dubbed ‘globsters’, a term invented by Ivan Sanderson). They can definitely become distorted to create the impression of a long neck, as verified by a photo of another beaked whale carcass published by Dinsdale (1966). The fact that the body of the Moore’s Beach carcass doesn’t much resemble that of a whale (at least, so far as we can tell from the surviving photos) might not mean much therefore, and it’s also irrelevant given the obvious data we can glean from the head.

Skull of the Moore’s Beach Monster. I mentioned above the fact that the skull of the carcass was removed and retained, and is even on display today. And here it is!

As in all beaked whales (or ziphiids), the skull bones posterior to the external nares are elevated, forming a crest that Moore (1968) termed the synvertex. In most beaked whales, the anterior margin of the synvertex extends dorsally so steeply that it's perpendicular to the long axis of the rostrum (in some taxa, the very top of the synvertex overhangs the base). Berardius differs from other ziphiid taxa in that the anterior margin of the synvertex is inclined at an angle of about 45° relative to the long axis of the rostrum. This is a primitive condition and – in part – explains why Berardius is thought to be among the earliest-diverging members of crown-Ziphiidae (Lambert 2005, Bianucci et al. 2007). Berardius also differs from most other ziphiids in having its mesorostral gutter partially filled by an ossified mesethmoid, and by possessing a rounded lump (formed from the interparietal or frontals) on the vertex (in between the nasals and supraoccipital). All of these features are clearly observed in the skull shown here.

The apically located, laterally compressed tooth pairs of Berardius are also diagnostic, but we can see that the tips of the Moore's Beach animal's dentaries are damaged, and as a consequence the teeth are entirely absent (so far as I can tell). I wonder why: did someone remove them from the skull before the CAS prepared it? The images were kindly provided by Thomas J. Gehling, who took them in 2004, and are used with permission. Thanks Thomas.

And that’s where we’ll end things. The focus of this article was of course B. bairdii, and back when I wrote the text above this was one of only two recognised (extant!) species of the Berardius genus, the other being Arnoux’s beaked whale B. arnuxii. However, 2019 saw the official naming of a third species: the relatively small Kurotsuchi or Sato’s beaked whale B. minimus Yamada et al., 2019. This is one of several whale species named in current times (others include Rice’s whale Balaenoptera ricei Rosel et al., 2021 and Ramiri’s beaked whale Mesoplodon eueu Carroll et al., 2021), all of which have been confirmed as new via molecular analyses.

Anyway… for previous TetZoo articles on sea monster carcasses and related topics, see…

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent, November 2019

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, October 2020

Morgawr and the Mary F Photos, February 2021

What Was the Montauk Monster? A Look Back to 2008, October 2021

This blog benefits from your support. Thank you to those who help via patreon!

Refs – -

Balcomb, K. C. Baird’s beaked whale Berardius bairdii Stejneger, 1883: Arnoux’s beaked whale Berardius arnuxii Duvernoy, 1851. In Ridgway, S. H. & Harrison, R. (eds) Handbook of Marine Mammals, Volume 4. Academic Press, pp. 261-288.

Bianucci, G., Lambert, O. & Post, K. 2007. A high diversity in fossil beaked whales (Mammalia, Odontoceti, Ziphiidae) recovered by trawling from the sea floor off South Africa. Geodiversitas 29, 561-618.

Chorvinsky, M. 1995. The Santa Cruz sea monster. Strange Magazine 15, 15.

Dinsdale, T. 1966. The Leviathans. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Lambert, O. 2005. Systematics and phylogeny of the fossil beaked whales Ziphirostrum du Bus, 1868 and Choneziphius Duvernoy, 1851 (Mammalia, Cetacea, Odontoceti), from the Neogene of Antwerp (north of Belgium). Geodiversitas 27, 443-497.

McLellan Davidson, M. E. 1929. Baird's Beaked Whale at Santa Cruz, California. Journal of Mammalogy 4, 356-358.

Moore, J. C. 1968. Relationships among the living genera of beaked whales with classifications, diagnoses and keys. Fieldiana : Zoology 53, 209-298.