Yes, it’s time once more to look at the convoluted and unusual tale of a real-life, supposed modern-day plesiosaur carcass…

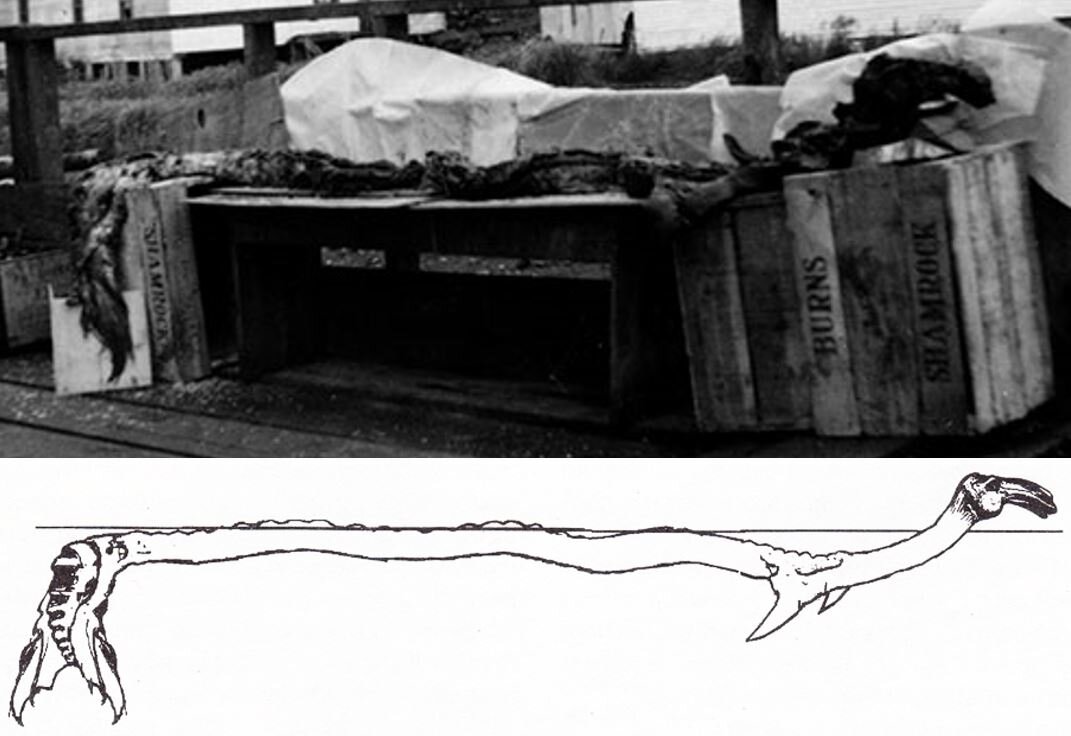

Caption: it’s 1937, and this long, slender object - apparently the carcass of a peculiar vertebrate animal - has been extracted from the stomach of a Sperm whale at a British Columbian whaling station… (images from Bousfield & LeBlond 1995).

Long-time readers of TetZoo – those who remember or read things from versions 2 (the ScienceBlogs years) and 3 (the SciAm years) – may remember the several articles there devoted to Cadborosaurus, the supposed sea monster of the British Columbian coast. Partly because those articles have been corrupted or paywalled by their hosters, I figured it’s time to republish the better part of my Cadborosaurus thoughts here at tetzoo.com. Plus I’ve just produced some quantity of text on the subject for one my TetZoocryptomegathreads at Twitter. Ok…

Cadborosaurus: the background. European colonists of coastal British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA claimed – from the 1880s onwards* – to witness a large sea monster in the region’s coastal waters. Sometimes said to have a head shaped like that of a camel or horse, sometimes said to be hump-backed or serpentine, and sometimes said to be furry or hairy, or scaly, or wrinkled, it became associated in particular with British Columbia’s Cadboro Bay. In 1933, editor and journalist Archie H. Wills at the Victoria Daily Times adopted the name Cadborosaurus for this mystery sea creature, a moniker first suggested in a letter written to the Victoria Daily Times by I. Vacedun in 1933.

* A possible 1791 account was also accepted by some researchers (LeBlond 2001).

Caption: at left, three classic, formative Caddy illustrations: Mattison’s 1964 drawings of the Fergusson and Walker 1897 sighting, and the 1933 newspaper illustration based on the Major Langley and F. W. Kemp sighting. At right: Archie H. Wills.

This name stuck and became the creature’s ‘official’ name, often abbreviated to ‘Caddy’. Wills wrote about Caddy often in the pages of the Victoria Daily Times and was seen by Caddy’s main recent proponents – Paul LeBlond and Edward Bousfield (more on them later) – as worthy of great accolade for this reason. Wills wrote of “being [Caddy’s] sponsor and protector”, and LeBlond and Bousfield even said “If anyone is to be credited with discovering Caddy and perhaps to be honoured by having his name linked to the official description, it should be A.H. ‘Archie’ Wills” (LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, p. 25).

Now, I don’t wish to sound rude, but I find this aggrandising naïve and perhaps ironic. Journalists and other people involved in the production of provincial newspapers are not, I’m sorry to say, impartial and unbiased reporters of events: they are very often (if not always) making decisions about what to cover in order to capture the zeitgeist and help sell newspapers! They’re often sensationalists unafraid to report things that are rumoured or half-believed, and some of them even have a track record of making things up in order to make news.

Caption: the Loch Ness Monster made it big in 1933, thanks in no small part to the Spicer sighting (two interpretations of which are which are depicted here - I do so like the Gino d’Achille one). I wasn’t the first to notice that Cadborosaurus made it big so soon after the Loch Ness Monster hit the news: Loxton & Prothero (2013) drew attention to this too.

Indeed, it’s no coincidence that Caddy sightings first really hit the news in 1933. This is the year in which Loch Ness Monster fever took the world by storm. Everyone was fascinated and many wanted a piece of the action. In their 1995 book on Caddy, LeBlond & Bousfield (1995) mentioned 1933’s Loch Ness Monster stories before discussing the Caddy accounts which made front-page news in British Columbia just a few months later (specifically, in October 1933). I maintain that this is no coincidence: I put it that popular interest in the Loch Ness Monster drove journalists on the west coast of North America (and elsewhere) to embellish and report their own similar water monster.

I’m pleased to say that Daniel Loxton and Don Prothero noted exactly the same thing in their 2013 book Abominable Science! (Loxton & Prothero 2013). Even better, they got confirmation from Wills himself. In an unpublished c 1985 manuscript kept at Greater Victoria Public Library, Wills wrote how the grim news of the time (the depression, Hitler’s rise to power…) encouraged him to “try and inject a bit of humor in the newspaper. Rumors were abroad that a sea serpent was disporting itself in our waters and I felt that if the story was handled circumspectly we might have a little fun” (Loxton & Prothero 2013, pp. 240-241). Dan Loxton (who wrote the sea serpent chapter in Abominable Science!) went on to link Archie Wills’ writings on Caddy with the then current fame of Nessie.

A further problem with Caddy is that there’s no “the creature”: if you look at the reports, people are clearly describing all manner of different things seen at sea, ranging from waves and bits of wood to swimming deer, big seals and more.

Caption: contrary to claims otherwise, Caddy sightings are not at all consistent. They describe encounters with a substantial diversity of things seen at sea. Image: Cameron McCormick.

Also telling is that Caddy proponents were quick to claim that confirmation of Caddy’s existence came from indigenous art and legend. They pointed to any and all bits of rock art, sculpture and oral history referring to big, predatory sea creatures as references to Caddy (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, LeBlond et al. 2014). But these images and stories reflect all sorts of things (mythified killer whales and pinnipeds, spirit beasts, mythical great serpents). To just lump them into the flesh-and-blood Cadborosaurus category ignores their diverse origins and independent backgrounds. Plus they don’t sound like Caddy anyway. Hiyitl'iik of the Manhousat people of Vancounver Island, for example, is said by cryptozoologists to be one and the same as Caddy (LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, p. 4), yet its name supposedly means ‘he who moves from side to side’ – something that Caddy is categorically thought not to do!! (Caddy is established in Bousfield and LeBlond’s works as a vertical undulator).

Caption: numerous piece of indigenous imagery have been linked with the concept of Cadborosaurus. We should be extremely sceptical of any and all such claims: they’re based on only the most superficial of similarities and ignore the actual stories behind these images and objects. Images: Bousfield & LeBlond (1995).

A Caddy carcass photo emerges. Anyway, fast forward to the early 1990s, a time which saw the exciting news that photos of a genuine Caddy carcass (hailing from the 1930s) had been discovered in some museum archives; there was a real creature at the bottom of things after all! Caddy had two main champions: Dr Edward L. Bousfield – a qualified zoologist specialising on amphipod crustaceans – and Dr Paul H. LeBlond, an oceanographer with special interests in oceanic waves, fisheries and coastal oceanography. I’m sad to say that Ed Bousfield, Caddy’s most vociferous proponent, died in 2016. I corresponded with him quite a lot, as you’ll see shortly. And Paul LeBlond – who I didn’t correspond with, but who kindly sent me a signed copy of his 2014 book (LeBlond et al. 2014) – is also no longer with us; he died in February 2020.

Caption: the late Dr Paul LeBlond. Image: Times Colonist (original here).

In their writings (books and a technical paper, read on), Bousfield and LeBlond drew attention to the mid-July 1937 discovery of a remarkable animal carcass, about 3.8m long, extracted from the stomach of a Sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus caught and killed off Langara Island near the Naden Harbour whaling station. Naden Harbour was on what were then called the Queen Charlotte Islands off the British Columbian coast; the archipelago is today known as Haida Gwaii.

Caption: location of Haida Gwaii, from (c) Google maps.

The carcass was noticed as the flensers – who were mostly people of east Asian identity – were opening up the whale’s stomach; they alerted their supervisor F. S. Huband. LeBlond and Bousfield tracked down an eyewitness, Jim Wakelen of Victoria, B.C., who remembered the event well. Wakelen was assistant to his father – the station’s blacksmith – during 1937 (LeBlond 2001). He recalled the carcass causing some excitement among the flensers and “all [the] station personnel came to gawk at it” (LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, p. 51). As usual in these sorts of stories, the point is made that everyone who regarded it as remarkable was already familiar with such creatures as six-gilled sharks, ragfish (a poorly known big ray-finned fish of the region) and big squid, and thus couldn’t possibly have been mistaken in their feeling that it was something new. I’m sceptical of this take, since even veteran seafarers and fishermen don’t know everything about the animals that occur where they live and work, and you should be sceptical of it too.

Huband decided to make a record of the specimen and had it prepared for photography. It was laid out on a worktable (some wooden packing cases were placed adjacent to the table to increase the available surface length) and white sheets were hung behind to tidy things up, One of the photos (or, a copy of it) was passed to the Victoria Daily Colonist (the rival publication to the Victoria Daily Times mentioned earlier) where it appeared on the front page of October 31st, 1937. It appeared again in the Vancouver Sun in May 1960.

Caption: one of the first ‘mainstream’ outings of the discovery (or… rediscovery?) of the Naden Harbour carcass — it’s coverage in this January 1993 New Scientist article by Penny Park.

Mention of the carcass was also made in the whaling station’s annual report, published in September 1937 in Fisheries New Bulletin. It was noted that the carcass was about 10 ft long, had a head recalling that of a large dog, “animal-like vertebrae” (err), and a tail “resembling a single blade of gill bone as found in whales’ jaws”. During their 1992 research, Bousfield and LeBlond discovered (thanks to Royal British Columbia Museum ethnologist Grant Keddie) Huband’s photo in the Provincial Archives at Victoria. This photo shows the scene at a slightly oblique angle, and it’s this one that Bousfield and LeBlond initially went public with. Perhaps coincidentally (I’m not sure), 1992 was also the year in which Bousfield and LeBlond spoke about Cadborosaurus at the American Society of Zoologists annual meeting.

It’s unusual for presentations on cryptids to be given at technical zoological meetings (albeit not unheard of), and a consequence of them giving this talk was (a) a crap-ton of media interest, and (b) a publication – albeit an abstract only – in the coveted pages of American Zoologist (Bousfield & LeBlond 1992). This abstract – the precursor to or ancestor of the 1995 monograph I’ll talk about in a minute – described how “photographs of specimens” were combined with eyewitness recollections and sketches in order to build a model of what this cryptid (unnamed in the abstract) might be like.

At this point (1992), Bousfield and LeBlond were saying that the animal’s phylogenetic affinities couldn’t be pinned down, and that it possessed “both reptilian and mammalian characteristics”. They were also bold enough to suggest that their British Columbian animal might have links to “marine and freshwater cryptids of the northern hemisphere including those of Loch Ness in Scotland, and Lake Okanagan” (Bousfield & LeBlond 1992). Ok.

Caption: at left, Ed Bousfield with images of the Naden Harbour carcass. At right, the Bousfield & LeBlond (1992) abstract from American Zoologist.

This conference presentation was picked up as a story worth covering by various journalists, so 1992 and 93 saw Cadborosaurus – in particular the existence of a photograph of a carcass – get airing in the mainstream press, often accompanied by a photo of a smiling Ed Bousfield pointing at the Huband photo. An especially good review of events was provided by Mike Dash in Fortean Times (Dash 1993). Dash (1993) noted that Bousfield and LeBlond’s American Society of Zoologists presentation saw them announce that Cadborosaurus was probably endothermic, predatory, and deep-diving, though Bousfield had earlier told The Economist that Caddy possessed “an elaborate (and hitherto quite unknown) respiratory system: tubercles lining the animals’ back acting as gills to pass water over highly vascularised tissue beneath” (Dash 1993, p. 47).

It was clear, I recall hearing, that Bousfield and LeBlond were putting together – or had already put together – a technical paper of some sort on the creature, and it was going to include a fairly in-depth take on its biology. Incidentally, this fed into the fact that the early 1990s seemed like an extraordinarily positive time for ‘scientific cryptozoology’ (an area I’ll be writing about some time soon).

Anyway… how, you might wonder, could Bousfield and LeBlond make bold proclamations about the animal’s biology and anatomy in the absence of an actual specimen? That might be a fair question, but it was obvious by this time that they were indulging in the sort of ‘creature building’ speculation common in the cryptozoological grey literature (Conway et al. 2013, Naish 2014), most famously the writings of ‘father of cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans.

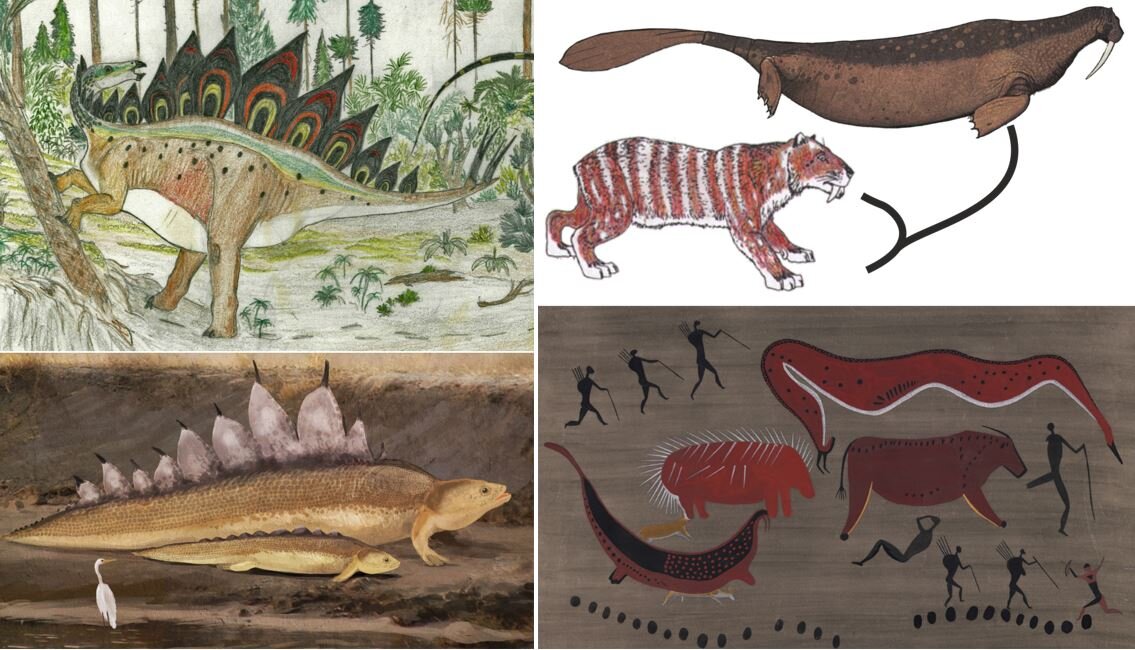

Caption: speculative ‘creature building’ has been, and remains, a prominent part of cryptozoological theorising. You have to make up your mind whether this is a good thing or not. These images are from Naish (2014) and incorporate elements produced by C. M. Kosemen (lower left), John Conway (cat-walrus at upper right), and unnamed artists from South Africa (lower right).

Indeed, Cadborosaurus as imagined by Bousfield and LeBlond – an aquatic mega-serpent with novel physiological adaptations, representing an entirely new, radically novel lineage without close living or fossil representatives – is very much built in the same mould as the imaginary sea serpents devised by Heuvelmans (1968) and certain of his followers.

More carcass photos are found. Fast forward to January 1995… Bousfield and LeBlond were aware that more photos must exist, since author and former fisherman William Hagelund had included one (showing the carcass at a different angle from that shown in Huband’s photo) in his 1987 book Whalers No More (Hagelund 1987). Hagelund had obtained this photo from the Vancouver Maritime Museum, and investigation here revealed that it was one of two additional photos of the carcass.

Caption: the Boorman ‘holotype’ photo of the Naden Harbour carcass, from Bousfield & LeBlond (1995). The photo shows lots more of the surrounding buildings and structures than normally shown.

These were included in a photo album compiled by G. V. Boorman of Victoria, B.C., entitled ‘Whaling in the Queen Charlotte Islands, 1937’. A duplicate set were also located in the Provincial Archives in Victoria. Boorman was first-aid officer at the whaling station. Boorman’s photos were sharper, and showed the carcass more clearly in lateral view, than Huband’s. Of the three known photos, the two Boorman ones were therefore preferred by Bousfield and LeBlond. Bousfield and LeBlond noted that no-one seems to have paid any of the three photos any serious interest over the years, and they were effectively unknown to the scientific community prior to Bousfield and LeBlond’s discussion of them.

Caption: the Boorman ‘paratype’ photo of the Naden Harbour carcass, from Bousfield & LeBlond (1995).

The monograph appears. During 1995, the interesting news arrived that Bousfield and LeBlond were including the photos in a formally published technical monograph on Cadborosaurus wherein they would formally name this creature, using the photos as critical evidence. Formal zoological papers on cryptozoological evidence are few and far between – especially those that have a positive or affirmative take on the alleged mystery beast – so this was exciting. I purchased a copy through the UK’s Centre for Fortean Zoology (I was an undergrad student at the time, interested in pursuing studies in fossil marine reptiles).

The backstory to the paper itself is interesting. Because it was published as Supplement 1 to Volume 1 of a new journal – Amphipacifica: Journal of Systematic Biology – it looked as if the journal was specifically launched in order that Bousfield and LeBlond could publish their Cadborosaurus paper. This technique (creating a new journal purely as a vehicle for a paper that you’ve been unable to publish elsewhere) has been used elsewhere in cryptozoology (Melba Ketchum and her colleagues infamously used it to publish their 2013 paper ‘Novel North American Hominins’). Was it being used here? Well, apparently not: I’m reliably informed by an amphipod specialist that Amphipacifica is in fact a worthy and respectable venue for amphipod-themed studies. Fair enough.

Two of the three members of Amphipacifica’s editorial board (Craig P. Staude and Phil Lambert) published – as part of an Editorial article – objections to the publication of Bousfield and LeBlond’s Cadborosaurus paper, specifically stating “… we are opposed to its publication as a formal species description for several reasons…” (Staude & Lambert 1995). Staude & Lambert (1995) went on to note their concerns about the usefulness of the photos, the anecdotal nature of the relevant eyewitness descriptions, and the absence of a holotype. Only one of the three journal editors was fully behind the paper’s publication… Ed Bousfield!

Caption: front cover and abstract of Bousfield & LeBlond (1995). I don’t know how common hard copies are; there are also a few pdf versions (of differing quality) kicking around.

Regardless of these differences of agreement, the 1995 monograph saw print. It’s a 25 page study that aims to lay out the case for Caddy’s existence and scientific validity, names it as a new living reptile species, and goes on to discuss its possible affinities, lifestyle and biology (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995). The keystone bit of evidence is the 1937 carcass or, rather, the three photos of it, since the carcass itself is of unknown whereabouts. Well, actually, a section of spine, a piece of tissue identified as baleen, and some skin – all supposedly pertaining to the carcass – were forwarded to either the Pacific Biological Station at Nanaimo, or perhaps the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria. It might be that specimens were sent to both institutions. It seems that something arrived in Victoria at least, since (as reported in the Victoria Daily Times on July 23rd, 1937), museum director Francis Kermode (in Victoria) identified the relevant remains as those of a “fetal baleen whale”. Nothing else is recorded, so the general feeling is that the specimen was lost, discarded, or not retained in the first place (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995). Kermode’s opinion has usually been taken to show that official interest in the carcass was non-existent (it was apparently responsible for the dismissal of the case by Bernard Heuvelmans; LeBlond 2001, p. 56), but this might not be accurate since famed zoologist and conservationist Ian McTaggart-Cowan at the British Columbia Museum thought Kermode’s dismissal inappropriate “and that the Naden Harbour carcass [was] indeed a valuable piece of evidence” (LeBlond 2001, p. 56).

Jim Wakelen (one of the observers of the carcass you’ll recall from earlier) provided more information in a phone conversation with Bousfield in 2007 (LeBlond et al. 2014). He said that the carcass was “coiled up and preserved in salt”, sent by boat to Vancouver, and then stored in acetone at a warehouse belonging to the American Whaling Company in Bellevue, Washington. This information sounds compelling and detailed, and sure does make it sound as if the carcass was retained and preserve. But, alas, there’s no record.

What do the photos show? We’re only left with the photos then. What do they show? They’re black and white, and (as noted earlier) depict the long, slender, dark carcass of a vertebrate animal laid out on a table and a series of packing cases. There’s what looks like a rectangular head at one end, a crumpled, adjoining ‘neck’ region, a sinuous, serpentine body, and a ragged, serrated region with what looks like a ragged tail fin.

Caption: the head of the Naden Harbour carcass as interpreted by Bousfield & LeBlond (1995). Can we really discern all the specific details they featured in their illustration? I don’t think so.

Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) produced a diagrammatic interpretation and noted further details which they thought they could see (note my wording there). They noted two pointed structures located at the neck-body junction and identified them as fore-flippers, and also emphasised the presence of oval tubercles located along the dorsal surface of the body (which number about 26). They also thought that a fluke-like structure was present at the rear end of the body and argued that it represented a highly modified limb. Adjacent to this was, they claimed, a short tail. We’ll look in detail at both of these body parts in a minute.

It’s made clear throughout the monograph – including in its title – that Cadborosaurus was interpreted by Bousfield and LeBlond as a reptile. Their systematics section lists it as ‘Class Reptilia, Subclass Euryapsida?, Order Plesiosauria?’ (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995). The question marks denote their allusion to uncertainty, but the point is clear that they were regarding it as a possible modern-day plesiosaur. This is extremely odd. As we all know, suggestions that plesiosaurs might have survived to the present and be the explanation behind ‘sea monster’ reports go back to the mid-1800s (Paxton & Naish 2019) and are ubiquitous in popular literature and culture.

Caption: is Cadborosaurus - as imagined by Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) - like a plesiosaur? I mean… at all like a plesiosaur?

Yet Caddy – which is purportedly serpentine, furry, with a camel-shaped head, ears or horns, and said to more via vertical undulation – is (if imagined as real) about as different from a plesiosaur as you could possibly imagine. Why on earth make this odd, wayward suggestion? Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) didn’t just push this idea due to social inertia, but aimed to justify it via anatomical data. They did this via their discussion and interpretation of specific anatomical details, but in order to see what they did and why they concluded what they did we really have to drill down on the details. It gets weird, but here we go…

Recall the pointed structures located close to the supposed junction between the ‘body’ and ‘neck’ sections? To emphasise that these are forelimbs, Bousfield & LeBlond (1995, p. 13) featured a reconstruction of the Caddy forelimb and showed it alongside the forelimb of the Jurassic plesiosaur Cryptoclidus, their aim being to show that both are extremely similar in shape and proportions, and thus add support to their view that Cadborosaurus is a plesiosaur.

Caption: Norman (1985) - here are both editions - is an ok book, but is it the book you should be citing in a technical study supposedly discussing plesiosaur anatomy? Nope.

They took their image of the Cryptoclidus forelimb from David Norman’s 1985 book The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs (Norman 1985)... which, for me, is a red flag: in a technical paper, you should consult and cite technical works, not popular books (unless the book is specifically relevant to your point or argument). Any check with a knowledgeable expert would have allowed them to find that the Cryptoclidus diagram featured in Norman (1985) is from Brown’s (1981) monograph on Cryptoclidus. In fact, Bousfield & LeBlond’s (1995) Cadborosaurus monograph doesn’t cite ANY technical work on plesiosaurs AT ALL! Not a good look in view of their ‘Caddy is a live plesiosaur’ argument. This sort of thing might not seem interesting or important, but it is to scientists who are paying attention, since it shows whether the authors concerned are checking the sort of sources they should and, frankly, doing research of a standard we expect. This is especially true of those cases where the research concerns a bold or remarkable claim: if you’re describing what’s claimed to be an actual real carcass of a bona fide sea monster, you better be checking and citing the technical literature properly, not relying on popular sources.

Caption: the Cryptoclidus reconstruction featured in Norman (1985) is from Brown (1981)… pretty annoying that it’s printed across two pages, and hence disappears into the spine when you try and photograph it.

The Cryptoclidus paddle shown in Norman (1985) – and, before that, in Brown (1981) – is in a raised, ‘upstroke’ pose. Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) didn’t want that, so they redrew it in a ‘downstroke’ pose. But this means that they then drew the paddle’s lower surface as if it were the upper surface. Aaand they labelled the digits back to front, putting digit 1 as digit 5 and so on. Sloppy work, guys.

A similar thing happened with the hindlimb, though here the story is even more complicated. Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) thought that the ragged end section of the Naden Harbour carcass represented a fluke-like propulsive organ but NOT a tail fluke. They claimed that distinct limb bones could be seen with the ‘fluke’: that sections corresponding to the thigh, shin and foot were all there, and that these had been co-opted into a novel anatomical structure, a ‘pseudo-fluke’ which involved both hindlimbs and a strongly reduced, serrated tail. Thanks to their enlargement of one of the Boorman photos, they claimed to be able to see a lot of anatomical detail on the tail: not just individual vertebral segments (!), but a midline ‘mid-dorsal crest’ formed of bony knobs, and two ‘dorso-lateral crests’, formed of additional bony knobs, on either side of it (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, p. 15).

Caption: Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) argued that numerous anatomical details could be identified in the ragged tail of the Naden Harbour carcass, that the observed section was only the right-side section of a symmetrical set of hindlimbs, and that the bony elements within this object could be homologised with the hindlimb of a plesiosaur (… and their picture wasn’t of a plesiosaur).

I’m sure I don’t need to tell you that it is absolutely not normal for vertebrate animals to be constructed such that their individual vertebral segments are visible on their exterior. Ok, you might argue that the carcass was imagined by Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) to be partially skeletonised due to the time it had spent in the whale’s stomach, but – no – their diagrams of Cadborosaurus in supposed living condition very clearly show that they evidently thought that this is exactly what it looked like all the time (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, p. 18). This is doubly confirmed by the colour paintings of ‘Caddy in life’ they supervised, like the very nice illustration by Susan Laurie-Bourque which appeared on the cover of their book (LeBlond & Bousfield 1995).

Caption: cover of LeBlond & Bousfield (1995). Somewhere online there’s a full version of the very nice painting that graces the cover, but I can’t find it today. I wonder where the original is? (I’d love to own it).

They argued, you’ll recall, that Cadborosaurus was a post-Cretaceous plesiosaur, so their argument was that the bones of this ‘pseudo-fluke’ could be homologised with the bones of a plesiosaur’s hind paddle. The published a diagram showing the ‘pseudo-fluke’ alongside a hindlimb labelled as that of the Jurassic plesiosaur Cryptoclidus (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, p. 15). Their two diagrams do look vaguely similar if you accept the Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) interpretation. But… oh dear. The ‘Cryptoclidus’ hindlimb they figure isn’t from Cryptoclidus at all; instead, it from a very different sort of animal quite distantly related to plesiosaurs: it’s from the Triassic pachypleurosaur Neusticosaurus, a marine reptile (about 1.2m long) that, while part of the same major group that includes plesiosaurs (termed Sauropterygia), isn’t a plesiosaur at all. Specifically, Bousfield & LeBlond (1995, p. 15) used a diagram from Carroll’s 1988 textbook (Carroll 1988), itself taken from a 1985 monograph (Carroll & Gaskill 1985) (where this animal was known as Pachypleurosaurus).

Caption: Neusticosaurus, a Triassic sauropterygian described and figured by Carroll & Gaskill (1985). The pelvis and hindlimb of this animal was figured by Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) as if the animal was a plesiosaur, which it isn’t.

Pachypleurosaurs, in fact, are not especially modified for aquatic life relative to plesiosaurs, and their limbs aren’t especially paddle-like, in contrast to plesiosaurs. If Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) really had compared the ‘pseudo-fluke’ of Caddy to the hindlimb of a plesiosaur, the similarity wouldn’t have been at all obvious. They pointed, for example, to the presence of a big and obvious tibia, fibula and ankle bones in the Caddy carcass and showed how these elements occupied a big proportion of the ‘pseudo-fluke’s’ length, yet these bones in plesiosaur hindlimbs are so strongly modified that they only contribute to a small section of hindlimb length and are dwarfed by the portion of the hindlimb made up of the digits.

Caption: plesiosaurs were relatively stiff-bodied animals where their wing-like paddles (connected to giant pectoral and pelvic bones) had long, slender phalangeal sections. Images (clockwise from upper left): Plesiosaurus specimen on show at Lyme Regis Museum (Darren Naish); plesiosaur hindlimbs from Williston 1925; Mary Anning’s famous Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus of 1824, in public domain.

IF their interpretation of the Caddy ‘pseudo-fluke’ as being pachypleurosaur-like was valid (which it wasn’t… read on), then all they would have succeeded in doing was showing that the pseudo-fluke had the exact same hindlimb elements as all other standard tetrapods. It wouldn’t be indicative of any link to plesiosaurs at all. Oh, and… as with the Cryptoclidus forelimb, they cited Norman (1985) for this diagram. But that’s a mistake, since Norman (1985) doesn’t figure Neusticosaurus at all, nor any diagram at all similar to it. They actually meant to cite Carroll (1988).

A lot of this is super-trivial. So let’s forget it and pretend that Bousfield & LeBlond’s (1995) point – that the Caddy ‘pseudo-fluke’ is similar to the sauropterygian hindlimb – is worthy of consideration. Is it? Well… meh. Firstly, if you look at the relevant photo of the Caddy tail, ALL the Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) claims about specific anatomical details being visible are highly suspect. Where they identify particular bones or other structures, all I see are lumps, bumps, variations in contrast and ambiguity. In short, their argument that we can see what they claim we can is down to pareidolia.

Caption: Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) - the Cadborosaurus monograph - explicitly and repeatedly compares the Naden Harbour carcass to plesiosaurs, and pushes the hypothesis that Cadborosaurus is a highly member of this reptile group. Both authors later denied that this is what they were promoting. This cartoon cladogram depicts (from top to bottom) a nothosaur, a plesiosaur, and Cadborosaurus as imagined by Bousfield & LeBlond (1995). Image: Darren Naish.

Furthermore, their argument that the fluke-like part of the carcass is a modified hindlimb (a hindlimb, specifically, from the carcass’s right side) is contingent on their argument that an identical structure was originally present on the carcass’s left but was missing when the carcass was photographed. Why should we accept that interpretation? It’s not all clear or obvious that this was the case: I’m more inclined to think that the fluke was a midline structure, not one of a pair.

In short, this whole ‘it has modified hindlimbs which can be likened to those of plesiosaurs’ argument is shot full of logical inconsistencies, factual errors and strange, embarrassing mistakes, and makes the study look like a bit of a farce.

The binomial and the type specimen(s). The key thing about the 1995 monograph isn’t just that Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) used it to push their idea of Caddy being (a) real and (b) a living plesiosaur; it was also a vehicle for the publication of a formal scientific name for the creature. They named it Cadborosaurus willsi Bousfield and LeBlond, 1995, the ‘willsi’ honouring Archie Wills, discussed earlier. Yes, they thought that the newspaperman who made the name Cadborosaurus famous should be honoured for his prescience (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, p. 12).

Caption: a Naden Harbour carcass montage, using images from Bousfield & LeBlond (1995).

As we’ve seen already, the carcass itself is of unknown whereabouts. There is no survival physical specimen. So how could Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) justify this name in the absence of what biologists call a Type Specimen? They argued that the PHOTOS should serve this role, and identified the best of the two Boorman photo as a holotype; the second Boorman photo and the Hubard photos were identified as paratypes (a paratype is a specimen that provides additional material relative to the holotype, bolstering its validity) (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, p. 9).

Cryptozoologists have argued on several occasions that we should, in an ideal world, do away with the idea that physical type specimens are needed for a species to be named. Bernard Heuvelmans – ‘father of cryptozoology’ – was particularly big on this idea (Heuvelmans 1986). After all, they want scientific recognition for key cryptids such that their existence is made official and more mainstream. The debate as to whether physical specimens are NEEDED as holotypes is not, in fact, exclusive to cryptozoology, and biologists of all sorts are still arguing about it (e.g., Polaszek et al. 2005, Dubois & Nemésio 2007, Donegan 2008, Marshall & Evenhuis 2015, Ceriaco et al. 2016).

Caption: a list of species have been described without the retention of type specimens. Here are a few, clockwise from top left: the Vietnamese snake Cryptophidion anamense, Blonde capuchin ‘Cebus queirozi’, White-cheeked macaque Macaca leucogenys, Galápagos pink land iguana Conolophus marthae. See my 2017 article Animal Species Named From Photos. Images: Wallach & Jones 1994; Mendes Pontes et al. 2006; Li et al. 2015; Gentile & Snell 2009.

In cases – like, when an organism appears critically endangered – I can understand that the ‘collection’ of a holotype (shorthand for killing it) is undesirable. But in a case like the Cadborosaurus one – where we’re so, so, so, so far from being sure that the animal is real in the first place – I’d argue that a physical holotype is a requirement. Photos – especially old, black and white, less-than-ideal photos prone to pareidolia from the 1930s – simply don’t cut it when it comes to cryptids.

And there ends SOME of my main criticisms of the Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) monograph. I could say a lot more (I haven’t discussed their behavioural and ecological speculations, nor their take on the Hagelund ‘baby Caddy’…). Their naming of the species is incredibly dodgy, their interpretation of it as a living plesiosaur is very, very odd and based on special pleading and a litany of mistakes and assumptions, and their claims about specific aspects of the putative animal’s anatomy don’t withstand the most cursory of examinations.

Caption: my (now quite dated) attempt to depict Cadborosaurus as it was imagined by Bousfield and LeBlond. I should draw a more accurate, more competent version one day. Image: Darren Naish.

How on earth did this disappointingly weak study make it through review? If you’re wondering: yes, it was reviewed. In fact, they listed five reviewers, among which were palaeontologists Dale Russell and Chris McGowan. Wow, this does not reflect well on them (Dale died last year).

Responses, published and otherwise. As mentioned earlier, the content you’ve seen discussed here was the subject of extensive discussion on the internet message boards and mailing lists that were the main arena of discussion back in the 1990s and early 2000s. I shared my thoughts on the study in 1999 – and then discovered immediately afterwards that a technical paper, written by qualified biologists Aaron Bauer and Anthony Russell (both known for their contributions to technical zoology; Bauer in particular is a world expert on gecko biology), had been published in Cryptozoology, specifically in response to Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) (Bauer & Russell 1996).

Because the journal Cryptozoology – and the International Society of Cryptozoology itself – was undergoing something of a crisis at the time (it was dying, basically), the publication of Bauer & Russell’s (1996) was a bit delayed. It’s generally cited as 1996 (as here), but I wonder if it was published later – I personally wasn’t aware of it until 1999. Anyway, this paper covers many of the same issues I’d pointed to, even noting that Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) had, variously, been utterly wrong and hilariously wrong in labelling plesiosaur paddles and so on. I get the impression that Bauer & Russell (1996) had been submitted for publication in Amphipacifica (perhaps as an opinion piece), but rejected or ignored. Incidentally, I happen to know that the Cadborosaurus monograph itself had been submitted for publication in Cryptozoology, but rejected.

So, what was the response from Bousfield and LeBlond on these offensives? Bauer & Russell (1996) didn’t evoke any published response, which was surprising since working scientists expect (or should expect) remarkable claims to be met with appropriate scepticism and, if appropriate, challenge and pushback. Actually, cryptozoologist John Kirk (who’s always been very much on the side of researchers like Bousfield and LeBlond) said in 2000 that he’d seen a refutation of the Bauer and Russell paper from LeBlond, but I guess it was never finished or published, perhaps because of the ISC’s death. A few brief comments were included in LeBlond (2001) and LeBlond et al. (2014), the main complaint being that Bauer & Russell (1996) had wrongly accused Bousfield & LeBlond (1995) of claiming plesiosaurian status for Caddy… even though they very obviously had done exactly this.

Caption: the key texts on Cadborosaurus. LeBlond & Bousfield (1995) and LeBlond et al. (2014) - the two books on the left - state the case for the creature’s existence. Loxton & Prothero (2013) and Naish (2017) - the two on the right - are critical of these claims.

Kirk also kindly (ahem) forwarded my online writings about the Bousfield and LeBlond monograph to Bousfield and LeBlond themselves. Ed wasn’t happy with my negative take on his work and also noted his dislike of Bauer and Russell’s critique. He objected strongly to my characterisation of Cadborosaurus as a ‘living plesiosaur’, his argument being (to paraphrase, not quote) “that’s not what we said!”. But – I said again – it IS what they said: their 1995 monograph is shot through with stuff positing a plesiosaurian identity for Cadborosaurus – it’s their primary contention! (well, that and the fact that Cadborosaurus exists in the first place; Bousfield & LeBlond 1995).

I also have to add, sadly, that Ed’s response (and subsequent communications) included misplaced attacks on myself and my colleagues whereby we were characterized as Ivory Tower elitist gatekeepers, punching down and squandering our big piles of science dollars. Our first communication of 1999 includes this gem: “Isn’t it about time that the scientific community, with its high-tech resources and significant funding [sic], made a more realistic contribution (than erudite and often misplaced criticism) to the full solution of this enigma”. Look, it’s true that some scientists are immensely privileged, wealthy individuals with access to large quantities of funding. But, for god’s sake, the very opposite is true for the majority of them, especially those in zoology and allied disciplines. I guess it didn’t occur to Ed that I was a Masters student at the time he saw my criticism of his work; that I was only able to do the academic work I was due to a bursary, and was doing all my work unfunded. My track record as a writer and researcher also shows that I’m the very opposite of an ivory tower elitist or a gatekeeper. So, in case it’s not obvious, his comments often rubbed me up the wrong way; they seemed more akin to the rantings of True-Believer cryptozoology fans than what we should expect from the experienced, respected, veteran scientist he was.

Caption: the Cadborosaurus section from Naish (2000). It mostly repeats content elaborated on elsewhere in the article you’re reading now.

Anyway, I never published a paper dedicated to Cadborosaurus, but I did publish a take on events in my 2000 sea monster article in Fortean Times (Naish 2000) and in my 2001 ‘Sea serpents, seals and coelacanths’ article in Fortean Studies 7 (Naish 2001). I was kinder in those articles about the Naden Harbour carcass than I am today, implying that it might really be the carcass of “highly unusual, apparently new type of vertebrate animal” (Naish 2001, p. 88). But I also said that the Naden Harbour carcass should be seen within the following context: those photos were taken at a time when Caddy was seen as both a local sensation and as a bit of a joke in the media, AND when people were – I contend – faking Caddy carcasses.

Caption: at left, the location of Camp Fircom; at right, Shuker’s 1996 The UneXplained.

The Camp Fircom carcass. Exhibit B here (the Naden Harbour carcass has to be Exhibit A) is the Camp Fircom carcass, another ‘Caddy carcass’ from British Columbia, supposedly found on the beach at Camp Fircom in October 1936. So far as I can tell from information online today, Camp Fircom is a church-owned campground on the south-east side of Gambier Island, near Vancouver. The name seems specifically associated with the camping site. Anyway, I first became aware of this object thanks to Karl Shuker’s coverage of it in his 1996 book The UneXplained (clearly published to take advantage of the popularity of The X Files) (Shuker 1996). Karl had obtained postcards depicting the object, and I though these significant enough to write up in a short paper.

You see, I don’t think the Camp Fircom carcass is a real carcass at all. In fact, I’m pretty confident that – to quote myself in the 1997 paper I published on it (which I really should make available as a pdf) – it’s a “montage of beach debris” (Naish 1997). I think that the body is a plant stem (probably kelp), the skull is a rock (perhaps with a bivalve shell serving as a pretend eye), and that the forelimbs (which might also be plant parts) have no connection to the rest of the object and have merely been conveniently placed (Naish 1997). Karl treated my idea with a fair and appropriate quantity of scepticism and suggested alternative identifications for parts of the object, but on balance I still think I’m right and that the Camp Fircom object isn’t a carcass at all.

Caption: my attempts to draw the Camp Fircom carcass, and the first page of Naish (1997).

Which is interesting, because here’s direct evidence that people in British Columbia were in the habit of making fake ‘Caddy carcasses’ in or around 1936. In my view, this weakens the idea that the Naden Harbour carcass might be real. I’ve been told (specifically, by Ed Bousfield) that this is irrelevant and has no bearing on the Naden Harbour case. I don’t agree. I think it hints at the fact that people in the area were, during the early 1930s at least, seeing snaky marine objects and thinking “ha ha, this could be another Caddy”.

Transfer that to the Naden Harbour carcass, and it raises the possibility either that the carcass was a deliberate hoax (the crew at the whaling station saw a long, snaky object and sought to make it into ‘a Caddy’), or that the crew saw a long, snaky object and – influenced by the expectations and news of the time – immediately imagined that a Caddy carcass is what it must surely be. It’s true that this idea is contingent on me being right about the Camp Fircom object being a ‘fake’. I think I’m right; I really can’t see the object as anything other than an assemblage of coastal bits and pieces. But as usual with these historical photos, it’s a hypothesis and there’s no way of testing it directly.

What was the Naden Harbour carcass, really? To bring this back to the Naden Harbour carcass, what could it have been if Bousfield and LeBlond’s claims (Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, LeBlond & Bousfield 1995) about it being a modern-day serpentine plesiosaur were wrong (as they surely were, and are)? This topic saw repeated discussion on the internet discussion groups of the 1990s and early 2000s mentioned earlier, some claiming that it could be identified as the carcass of an unknown animal, others that it couldn’t be matched with a known species.

Caption: if you know anything about sea monster carcasses, you’ll be familiar with the ‘pseudoplesiosaur’ idea. At left, the Zuiyo-maru carcass of 1977. At right: Basking shark decomposition and the creation of a pseudoplesiosaur as illustrated by Markus Bühler.

Ben Speers-Roesch (today, a qualified marine biologist, but back then an amateur cryptozoologist who edited a desktop cryptozoology journal, The Cryptozoology Review) argued in 2000 that it was a misidentified Basking shark carcass. As you’ll know if you’re at all familiar with stories about sea monster carcasses, the rotted remains of ‘sea monsters’ have, time and time again, turned out to be Basking shark carcasses. In the case of the Naden Harbour carcass, Ben argued that the body segments of the carcass corresponded well to shark vertebrae, and that both the head and tail could be interpreted as those of a mangled shark if imagined as twisted and distorted. Of additional relevance is that Basking shark carcasses have – on one or two occasions – been discovered in Sperm whale stomachs, so there is a precedent for the situation reported from Naden Harbour. I don’t think Ben’s idea is that bad, and maybe it’s correct. But I don’t see it as especially convincing, since the diagnostic anatomical traits I’d like to see in the photos (concerning key details of the skull or vertebrae) aren’t obvious to me, nor indeed visible at all.

I think there’s another possibility worth considering, which I don’t regard as a slam dunk either, but as at least worth considering. A few years ago I learnt that sturgeons have a rectangular, gently curved neurocranium that has a squared-off anterior end. None of this is obvious in the live animal, by the way: you can only see it in skeletonised remains. This got me wondering: could the Naden Harbour carcass be the remains of a sturgeon? Sturgeons have a heterocercal tail (that is, where the dorsal lobe is longer and bigger than the lower one), and it could be that the ragged tail of the Naden Harbour carcass conforms to the dorsal lobe. Sturgeons also have a row of dorsal scutes along the top of the body; perhaps this explains that line of oval knobs visible along the length of the Naden Harbour carcass.

Caption: could the Naden Harbour carcass be a decomposed sturgeon? A few details are suggestive.

Finally, what about distribution? The White sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus occurs in the British Columbia region, where it’s anadromous (meaning that it migrates into freshwater to breed) and occurs in estuaries and other marine places during part of the year. Theoretically, a dead one could get washed out to sea at any time of year. It matches anatomically with the description above, and overlaps with the Naden Harbour carcass in size, the record length being over 6m (you’ll recall that the Naden Harbour carcass was about 3.8m long). Is, then, the carcass really that of a decomposed sturgeon, possibly one swallowed by a Sperm whale? In the absence of parts of the carcass, we can’t say. But I put it out there as an idea which is way more likely than the possibility that it was a modern-day serpentine plesiosaur. The idea was briefly discussed in my 2017 book Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017).

How did Bousfield and LeBlond’s 1995 hypothesis (that Caddy is a post-Cretaceous plesiosaur) fare among those cryptozoologists more inclined to regard Caddy as real? Bousfield & LeBlond (1995, pp. 8-9) noted that Caddy was probably one and the same as the Merhorse, one of Heuvelmans’s (1968) sea monsters, interpreted by him as a novel giant pinniped (Heuvelmans 1968). And the idea that Caddy – if real – might be mammalian rather than plesiosaurian has remained the more ‘mainstream’ take within the cryptozoological community… which is pretty funny: Bousfield and LeBlond set out to convince their academic colleagues of their hypothesis, and yet they didn’t even convince their closest allies and supporters.

Caption: Cadborosaurus had its precursor in ‘Halshippus’, the Merhorse of Heuvelmans (1968).

In one of the most widely consulted books on sea monsters – Karl Shuker’s In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (Shuker 1995) – a basilosaurid identity is preferred for Caddy (the idea that basilosaurid whales have survived to the present is a very popular idea in the history of cryptozoology). There’s also Pasquale Saggese’s 2005 proposal that Caddy might be a long-necked sirenian (Saggese 2005). I think this is a non-starter, but it is, again, a fun example of the SpecZoo ‘creature building’ component so prevalent in cryptozoology (Naish 2014).

Caption: Saggese’s (2005) speculative illustrations of Caddy as a giant, long-necked sirenian. Because Saggese interpreted the animal as a mammal, he argued that it should be renamed ‘Cadborotherium’. The cursor arrow features in the original article.

One more issue before I stop. Central to Bousfield and LeBlond’s arguments on the Naden Harbour carcass is that the object represents the same animal that witnesses claimed to see, alive, in the waters off and around British Columbia. But is there a reason to think this really is the case? If you go through all the alleged Caddy eyewitness accounts (e.g., Bousfield & LeBlond 1995, LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, LeBlond et al. 2014), there are lots of discrepancies. Among those reporting a horse- or camel-like head, for example, there’s mention of ears or horns… which aren’t present on the Naden Harbour carcass. As I noted earlier in this article, I think that sightings of live ‘Caddy’ animals actually involve all kinds of things (swimming deer, surfacing elephant seals, whales entangled in debris and so on), and a critical take shows that there’s no reason to mass them all together (Naish 2017).

That’s where we’ll end things. There’s much more to the Cadborosaurus saga, easily enough for a book. In fact, two books do discuss the creature (LeBlond & Bousfield 1995, LeBlond et al. 2014), but only from the point of view of it being a real, undiscovered novel marine vertebrate, not from the more critical, sceptical stance discussed here.

I’ve written about Cadborosaurus a lot here at Tetrapod Zoology, but – as noted right at the start of this very long article – those pieces have been corrupted, destroyed or paywalled by the companies now hosting those articles, which is not my fault. Links to wayback machine versions are included below…

Cadborosaurus and the Naden Harbour carcass: extant Mesozoic marine reptiles, or just bad bad science?, September 2006

A baby sea-serpent no more: reinterpreting Hagelund’s juvenile Cadborosaurus, September 2011

The Cadborosaurus Wars, April 2012

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Animal Species Named From Photos, February 2017

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent, November 2019

Refs - -

Brown, D. S. 1981. The English Upper Jurassic Plesiosauroidea (Reptilia) and a review of the phylogeny and classification of the Plesiosauria. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Geology Series) 35, 253-347.

Bousfield, E. L. & LeBlond, P. H. 1992. Preliminary studies on the biology of a large marine cryptid in coastal waters of British Columbia. American Zoologist 32, 2A.

Bousfield, E. L. & LeBlond, P. H. 1995. An account of Cadborosaurus willsi, new genus, new species, a large aquatic reptile from the Pacific coast of North America. Amphipacifica 1 (supplement 1), 3-25.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Palaeontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman & Co, New York.

Carroll, R. L. & Gaskill, P. 1985. The nothosaur Pachypleurosaurus and the origin of plesiosaurs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 309, 343-393.

Ceriaco, L. M. P., Gutierrez, E. E. & Dubios, A. 2016. Photography-based taxonomy is inadequate, unnecessary, and potentially harmful for biological sciences. Zootaxa 4196, 435-445.

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume I. Irregular Books.

Dash, M. 1993. The dragons of Vancouver. Fortean Times 70, 46-48.

Donegan, T. M. 2008. New species and subspecies descriptions do not and should not always require a dead type specimen. Zootaxa 1761, 37-48.

Dubois, A. & Nemésio, A. 2007. Does nomenclatural availability of nomina of new species or subspecies require the deposition of vouchers in collections? Zootaxa 1409, 1-22.

Hagelund, W. 1987. Whalers No More. Harbour Publishing, Madeira Park, British Columbia.

Heuvelmans, B. 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Heuvelmans, B. 1986. Annotated checklist of apparently unknown animals with which cryptozoology is concerned. Cryptozoology 5, 1-26.

LeBlond, P. H. 2001. Caddy – an update. In Heinselman, C. (ed) Dracontology Special Number 1: Being an Examination of Unknown Aquatic Animals. Craig Heinselman (Francestown, New Hampshire), pp. 55-59.

Loxton, D. & Prothero, D. R. 2013. Abominable Science! Columbia University Press, New York.

Marshall, S. A. & Evenhuis, N. L. 2015. New species without dead bodies: a case for photo-based descriptions, illustrated by a striking new species of Marleyimyia Hesse (Diptera, Bombyliidae) from South Africa. ZooKeys 525, 117-127.

Naish, D. 1997. Another Caddy carcass? The Cryptozoology Review 2 (1), 26-29.

Naish, D. 2000. Where be monsters? Fortean Times 132, 40-44.

Naish, D. 2001. Sea serpents, seals, and coelacanths: an attempt at a holistic approach to the identity of large aquatic cryptids. Fortean Studies 7, 75-94.

Naish, D. 2014. Speculative zoology. Fortean Times 316, 52-53.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters. Arcturus, London.

Norman, D. 1985. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Salamander, London.

Polaszek, A., Grubb, P., Groves, C., Ehardt, C. L. & Butynski, T. M. 2005. What constitutes a proper description? Response. Science 309, 2164-2166.

Saggase, P. 2005. Cadborosaurus willsi: attributive inquiry. Bipedia 24.5.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1995. In Search of Prehistoric Survivors. Blandford, London.

Staude, C. P. & Lambert, P. 1995. Editorial… an opposing view. Amphipacifica 1 (supplement 1), 2.