We might – right now – be in the Age of Peak Azhdarchid…

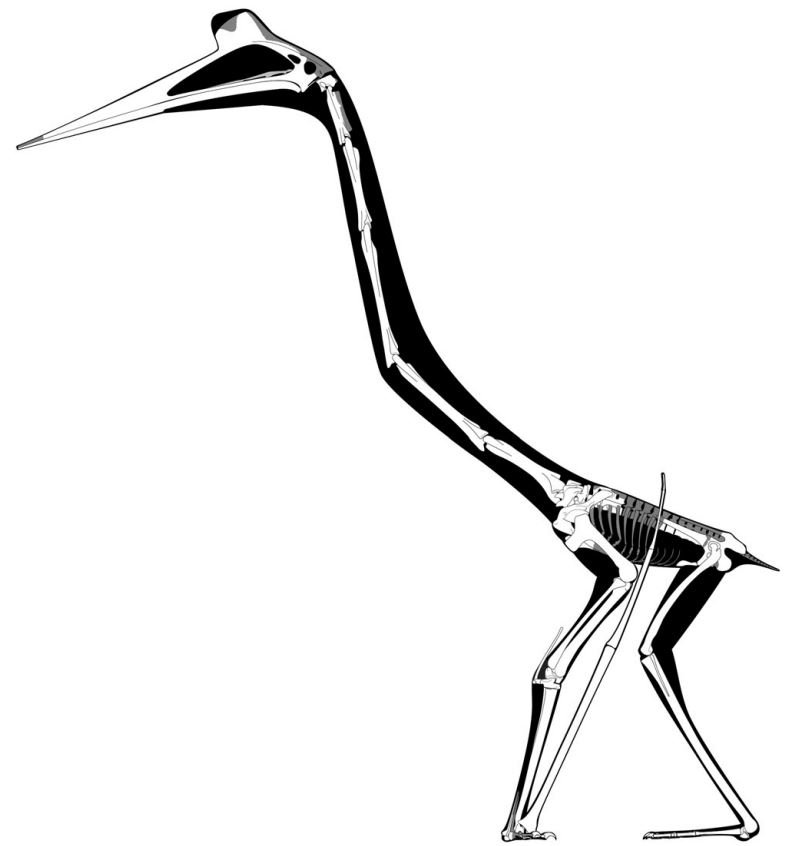

Caption: Padian et al.’s (2021) brand-new skeletal reconstruction of Quetzalcoatlus. It seems that the hindlimbs have been made too long.

If you’re in the habit of following news about Mesozoic tetrapods – especially those of the Late Cretaceous – it might be obvious that recent years have seen a great burst of discoveries pertaining to azhdarchids, the highly distinctive, spectacularly odd pterodactyloid pterosaurs famous for the long necks and giant sizes of some species.

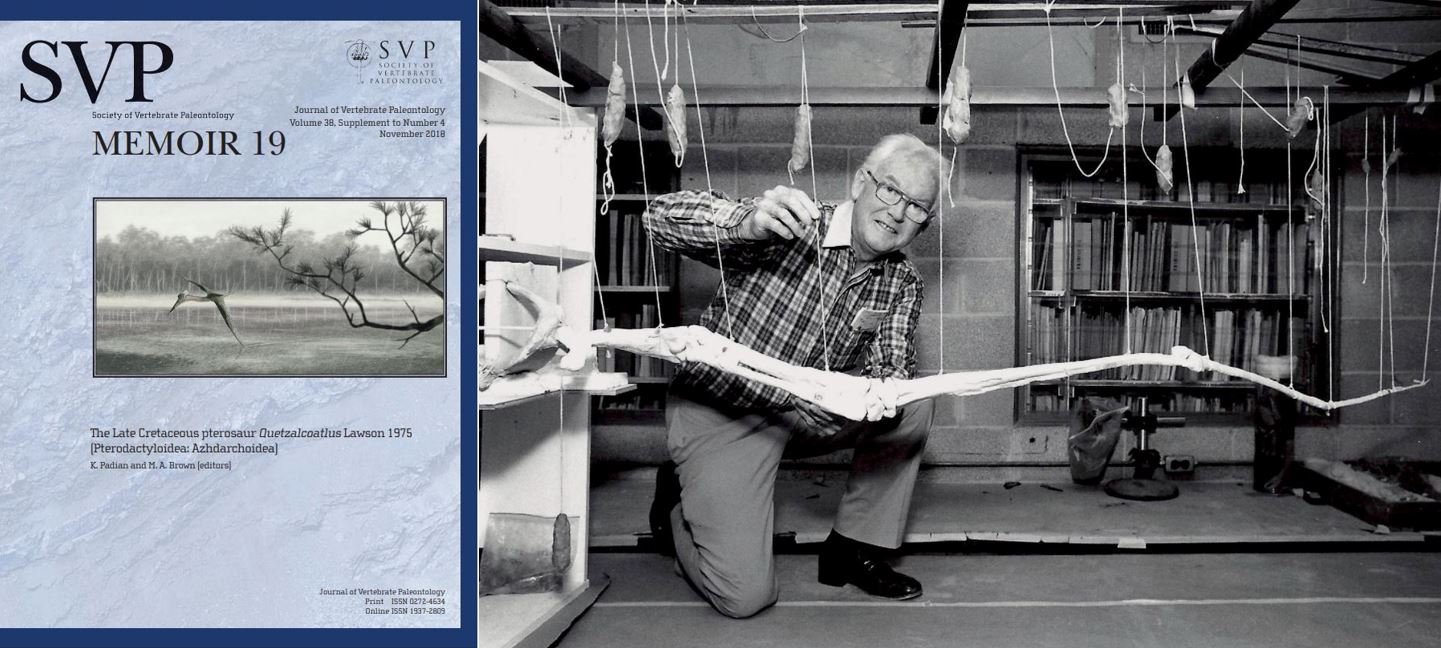

Caption: the Quetz Monograph is real (does the printed copy really still say ‘2018’ on the cover?). At right: Wann Langston with an articulated Quetzalcoatlus wing. Images: (c) Society of Vertebrate Paleontology; (c) University of Texas at Austin/Jackson School of Geosciences.

Azhdarchids have only been known to science since the 1970s when Doug Lawson named Quetzalcoatlus from the Late Cretaceous of Texas. Finds made by Lev Nesov in Kazakhstan about a decade later allowed him to name the new pterosaur group Azhdarchidae, to which Quetzalcoatlus was eventually shown to belong. Nesov thought that azhdarchids were a subgroup of pteranodontids (named for the toothless, sea-going Pteranodon of North America’s Western Interior Sea) but later studies showed that azhdarchids were something else entirely and not close to this group at all. More recent analyses of pterosaur phylogeny find azhdarchids to be part of a group that includes the toothless tapejarids and thalassodromids, all of which are united within the clade Azhdarchoidea.

The Quetz Monograph Lives. The Peak Exemplar of azhdarchids – indeed, of Cretaceous pterosaurs – is the gigantic Quetzalcoatlus northropi, named by Douglas Lawson in 1975 for bones from the Javelina Formation of Texas (Lawson 1975a, b). Lawson didn’t include that name in his initial published report on this animal (Lawson 1975a); instead, it appeared in a follow-up paper that arose as a piece of technical correspondence (Lawson 1975b). A 2017 ICZN petition, led by Brian Andres, aimed to have that technically unsatisfactory publication regarded as the official venue for the name.

Caption: a 1970s-era Doug Lawson, holding the enormous humerus of Q. northropi. I recently interviewed Doug and hope to use the text here at some point. Image: (c) University of Texas at Austin/Jackson School of Geosciences.

Well known in the pterosaur research community is that a second, smaller Quetzalcoatlus species was also discovered in the Javelina. This was described preliminarily by Alex Kellner and the late Wann Langston in 1996 (Kellner & Langston 1996), and Langston planned to produce a definitive, thorough description of both the small and large Quetzalcoatlus at some point. He was unable to complete this, and the absence of this work has been frustrating and oft lamented. The second Quetzalcoatlus species was referred to by Kellner & Langston (1996) as ‘Quetzalcoatlus sp.’, ‘sp’ being shorthand for ‘unnamed species’. I’ve always pronounced it ‘spuh’ because I spent about half of my life devising my own pronunciations for words I never heard anyone else say.

Caption: cover art of the Quetz Monograph, produced by some guy called John…. Conway?

Today (8th December 2021) sees the news that the Quetzalcoatlus monograph is – at long last – out, AND it’s open access and thus available to all. Published as part of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s Memoir series and fronted by Kevin Padian and Matthew Brown, the work is a collection of six contributions that review the discovery and distribution of Quetzalcoatlus, explore its palaeoenvironmental setting, describe its anatomy, and interpret its phylogenetic position and functional morphology (Padian & Brown 2021). It is the definitive work we’ve been waiting for and will be used as the standard reference on azhdarchids for the foreseeable future. I must get a hardcopy. The University of Texas have announced things via a press release; read it here.

Of the many important things here, one is that ‘Quetzalcoatlus sp.’ finally gets a name. It’s Q. lawsoni Andres & Langston, 2021. Q. lawsoni has a wingspan of 4.5 m and its metre-long skull preserves the anterior part of a low sagittal crest. Andres & Langston (2021) report a massive list of diagnostic traits for this species that extend across a substantial portion of the skeleton. Skull material is lacking for Q. northropi, by the way.

My biases of course mean that I’m especially interested in seeing how the terrestrial stalking hypothesis of Witton & Naish (2008) has fared in view of all this new data. It has fared well, the contributions here concluding that the Quetzalcoatlus species were stork- and heron-like predators of “terrestrial and shallow-water” environments (Padian et al. 2021), though the lack of wading adaptations makes me think that more emphasis should be placed on the “terrestrial” side of things there.

Caption: the Witton & Naish (2015) infographic, in which we aimed to graphically summarise the main support for the terrestrial stalking model. From Witton & Naish (2015).

The ‘Javelina Tupuxuara’ is named… twice. It’s not uncommon for the literature to feature an interesting fossil specimen that’s ‘wrongly’ attributed (via a published caption or label) to a known taxon, and which then becomes the stuff of legend for years or decades. In the pterosaur world, a classic example is TMM 42489-2, originally figured in Peter Wellnhofer’s 1991 book where it was labelled as Quetzalcoatlus. This specimen is obviously not referable to Quetzalcoatlus, and one of its distinctive features (the depth of that part of the premaxilla dorsal to the nasoantorbital fenestra) looks a bit like the condition present in the thalassodromid Tupuxuara (I still wish that Thalassodromidae had been named Tupuxuaridae, it would make so much more sense for historic reasons).

For that reason, Martill & Naish (2006) identified TMM 42489-2 as a Texan thalassodromid. My hypothesis was that the specimen would prove to be a new species of Tupuxuara. However, our claim was and is arguable, and we were smacked down by Mark Witton (albeit only in a blog article). Mark argued that the specimen weren’t no thalassodromid, but was actually an azhdarchid. I think Mark made the same point in his book of 2013 (I can’t check as my copy has been stolen). I’m inclined to agree with him.

Since then, the general feeling has been that TMM 42489-2 is an unnamed, new azhdarchid. Fast forward to this year, and Hebert Bruno Campos has acted on this, and named it Javelinadactylus sagebieli Campos, 2021. Therein, it is classified as a thalassodromid (Campos 2021), this harking back to what Martill & Naish (2006) proposed.

Caption: at left, TMM 42489-2 as figured by Campos (2021). At right, a speculative reconstruction depicting this animal as a thalassodromid. Scale bar in both = 10 cm. Images: Campos (2021).

Here’s where we come back to the Quetz Monograph. Andres & Langston’s (2021) study of Quetzalcoatlus morphology and taxonomy doesn’t just name Q. lawsoni, it also gives a new name to TMM 42489-2. On the basis of numerous diagnostic features in the skull as well as in the (previous undiscussed) neck vertebrae, this animal is named Wellnhopterus brevirostris Andres & Langston, 2021, ‘short-beaked Wellnhofer’s pterosaur’. Peter Wellnhofer is a much respected German pterosaur expert.

We thus have two names for the same taxon. It is unfortunately not uncommon in palaeontology for authors to be aware of the unpublished or in-prep work of others, and to then quickly rush out a paper that aims to name the same taxon. I will not, of course, make any accusations here, but I do know that certain of the authors involved in this situation were aware of the in-prep work of the others. I am reliably informed by Tyler Greenfield that Wellnhopterus brevirostris is now considered officially published, whereas Javelinadactylus sagebieli is still classed as an “advance online publication” and is thus not an “available publication” according to Article 9.9 of the ICZN. The name Wellnhopterus is thus the one we should use.

Images: the more we’ve learnt about azhdarchids, the more it seems that they were variable in proportions, size and shape. Some would have looked extremely slender in the neck, and this is especially true for the very large Arambourgiania from Jordan. Image: Mark Witton, taken from here.

Europe has azhdarchids too. It isn’t wrong to associate azhdarchids with North America, Asia or Afro-Arabia given the fossils that come from those regions (most famously, Quetzalcoatlus, Nessov’s Azhdarcho and Arambourgiania from Jordan). However, Europe has been important in the azhdarchid story since the 1990s, mostly thanks to Eric Buffetaut et al.’s description of the giant, robust Hatzegopteryx from Romania (Buffetaut et al. 2002, 2003, Naish & Witton 2017).

Neck vertebrae and other remains from the latest Cretaceous of France (e.g., Buffetaut et al. 1997) and Spain (e.g., Buffetaut 1999, Company et al. 1999) confirm azhdarchid presence in western Europe, plus of course there is Eurazhdarcho and Albadraco from Romania in addition to unnamed, additional taxa from Late Cretaceous Romania too. The phylogenetic placement of these various animals is somewhat uncertain but at least some appear to be from the same region of the cladogram as Azhdarcho.

Caption: it’s not the best photo, but this oblique view of the underside of the Mistralazhdarcho mandible gives you some idea how compressed these parts of the skull are. The tip of the element is to the left. Image: Darren Naish.

Additional European members of the group have turned up even more recently. One animal that grabbed my attention in particular is Mistralazhdarcho maggi Vullo et al., 2018 from the Campanian of southern France. The type specimen consists of a partial mandible as well as various vertebrae and wing elements. I examined this material while in Brussels in 2013 and was impressed with how narrow and pointed the mandible’s tip is, my thought at the time being that its elongation ratio (a measurement of length vs width) would likely be diagnostic. The Mistralazhdarcho holotype had an estimated wingspan of 4.5 m but it wasn’t mature, so fully grown individuals were suggested to have wingspans of between 5 and 6 m (Vullo et al. 2018).

Aerotitan and azhdarchids – or not – in South America. In 2012, Fernando Novas and colleagues reported a partial (supposed) rostrum from the Campanian-Maastrichtian Allen Formation of Argentina as that of the new azhdarchid Aerotitan sudamericanus. This was excellent news, confirming the existence of reasonably big azhdarchids in South America (its wingspan is estimated at 5 m).

Caption: Aerotitan compared to Alanqa, a montage featured by Novas et al. (2012), and which treats the Aerotitan holotype (A and B, and visualised on a Quetzalcoatlus skull in E) as a rostrum fragment instead of a mandibular one. From Novas et al. (2012).

Aerotitan has recently been re-evaluated by Pêgas et al. (2021) who argue that the holotype is not a rostrum, but the anterior part of the mandible (both elements are easy to confuse in azhdarchids, evidently). It is superficially similar to the Mistralazhdarcho mandible, and in fact Pêgas et al. (2021) found both to be closely allied members of Azhdarchidae, close also to the especially slender-necked Arambourgiania. This may or may not have implications for the appearance of Aerotitan.

Caption: Aerotitan (at left) and Mistralazhdarcho (right) compared. Aerotitan is depicted here as a rostrum, but if it’s a mandible it should of course be depicted the other way up. Scale bars in both = 5 cm. Images: Novas et al. (2012); Vullo et al. (2018).

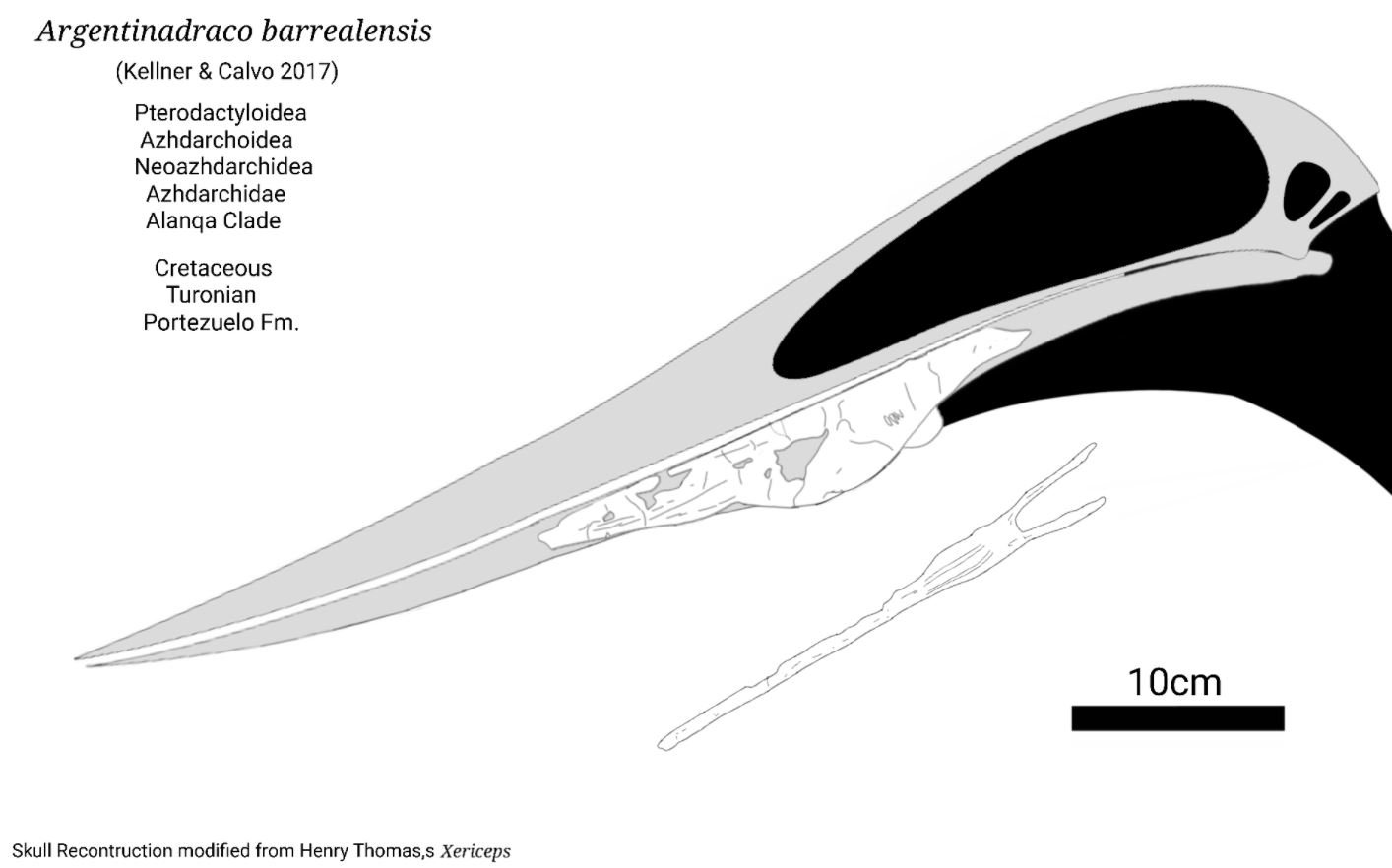

A second recently named South American taxon – Argentinadraco barrealensis from the Portezuelo Formation of Argentina, named in 2017 – is known from a mandible that possesses a series of prominent ridges and grooves on the mandibular symphysis and also exhibits a prominent bony bulge on the jaw’s underside (Kellner & Calvos 2017). Though published as a possible azhdarchid, it might be a chaoyangopterid (Pêgas et al. 2021), a phrase that might be moderately familiar by the time you get to the end of this article. The size of the Argentinadraco mandible is suggestive of a 3-4 m wingspan, so this also wasn’t a giant.

Are any properly big azhdarchids (or azhdarchid-like azhdarchoids) known from the South American record? Stay tuned. Oh, how cryptic…

Caption: the complete skull and mandible shape of Argentinadraco is currently unknown, but here’s one plausible reconstruction. Why various of these animals had ventral convexities on their lower jaws is unknown. Image: Dean Schnabel (twitter account here). Used with permission.

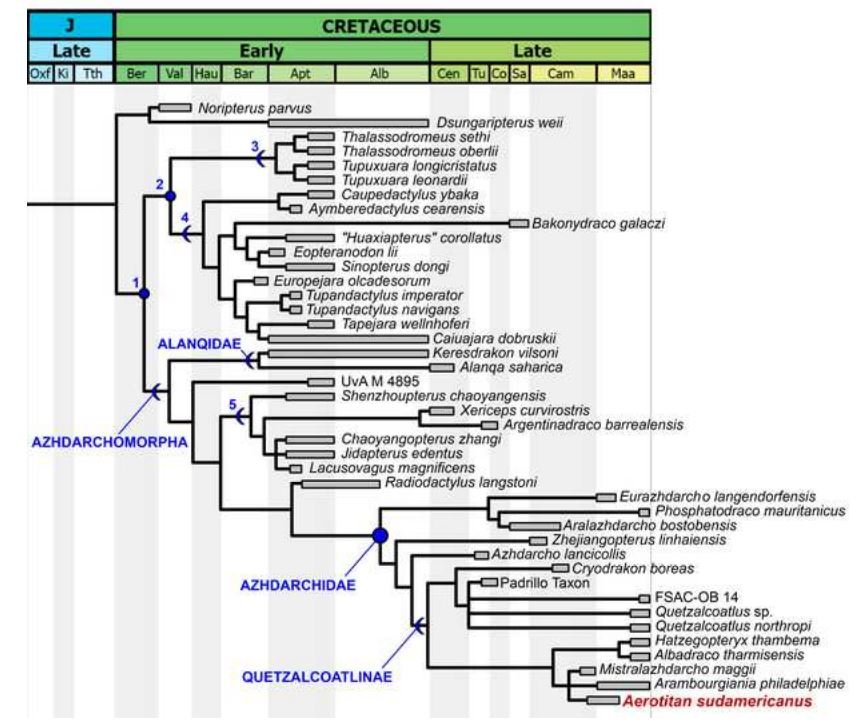

Alanqua and other alanqids, the recognition of a new azhdarchoid clade. I like Pêgas et al.’s (2021) paper, in part because it features a new phylogenetic analysis which both finds an interesting structure within Azhdarchoidea and proposes a new taxonomy. Following the works of Unwin and Andres et al., these authors recognise a node-based Azhdarchidae (sensibly anchored on Azhdarcho itself, in addition to Phosphatodraco and Quetzalcoatlus) which is close to Chaoyangopteridae. Within Azhdarchidae, they find animals like Eurazhdarcho, Phosphatodraco and Azhdarcho to be outside a clade that includes the giants (Pêgas et al. 2021), and they use the already existing name Quetzalcoatlinae for the latter. This is broadly consistent with previous suggestions regarding azhdarchid phylogeny (Vremir et al. 2013, Longrich et al. 2018), though a more inclusive version of Quetzalcoatlinae has been used elsewhere (Andres 2021).

Caption: azhdarchoid phylogeny as per Pêgas et al. (2021), showing the new Alanqidae as outside the azhdarchomorph clade that includes chaoyangopterids (5 here) and azhdarchids. I also like the fact that dsungaripterids are not nested here within Azhdarchoidea, a surprising position supported by some other researchers. Image: Pêgas et al. (2021).

One of their findings is that the Alanqa holotype from Morocco is – when interpreted as a mandible (it has sometimes been interpreted as a rostrum) – very similar to Keresdrakon vilsoni Kellner et al., 2019 from Brazil, the two sharing an especially slender jaw-tip and a V-shaped ‘dentary eminence’ located close to the symphysis. Accordingly, both are united within the newly recognised Alanqidae, found by Pêgas et al. (2021) to be outside the clade that includes chaoyangopterids and azhdarchids. It would be useful for this ‘azhdarchid-like azhdarchoid clade that includes Azhdarchidae itself’ to have a name, and thus we get Azhdarchomorpha…

Caption: the incomplete skull of Keresdrakon, associated with a partial skeleton and preserved in a Late Cretaceous desert setting. The tip is to the right (cra = skull; man = mandible; q = quadrate), and the convex dentary crest should be obvious. Image: Kellner et al. (2019).

I was on the Moroccan field excursion that resulted in the discovery and publication of Alanqa and was thus among the first pterosaur experts to ever see it, though I wasn’t included in the study itself (thanks guys). Alanqa was initially described as an azhdarchid, was suggested at one point (I recall a Society of Vertebrate Paleontology talk) to be a chaoyangopterid, and has also been suggested to be a thalassodromid (Longrich et al. 2018, Andres 2021). This new proposal helps explain this disagreement: in some respects, alanqids are generalised enough to possess features seen in most other azhdarchoid groups, yet also have unique features of their own.

High diversity in the Kem Kem. Azhdarchids (or, at least, azhdarchid-like pterosaurs) have been known from the so-called ‘Kem Kem’ or ‘Continental Intercalaire’ of northern Africa since the late 1990s when Wellnhofer & Buffetaut (1999) reported a number of partial mandibles and/or rostra. As we’ve seen above, Alanqa from the Kem Kem – named for a partial mandible – was published in 2010. Rodrigues et al. (2011) published some post-cranial remains as well as another partial mandible. Since then, a number of other azhdarchids and/or azhdarchid-like pterosaur specimens have been reported, mostly from Morocco…. mostly known from yet more partial mandibles. Here, we veer increasingly away from my intended emphasis on azhdarchids, since it’s looking increasingly likely that these animals aren’t members of that group…

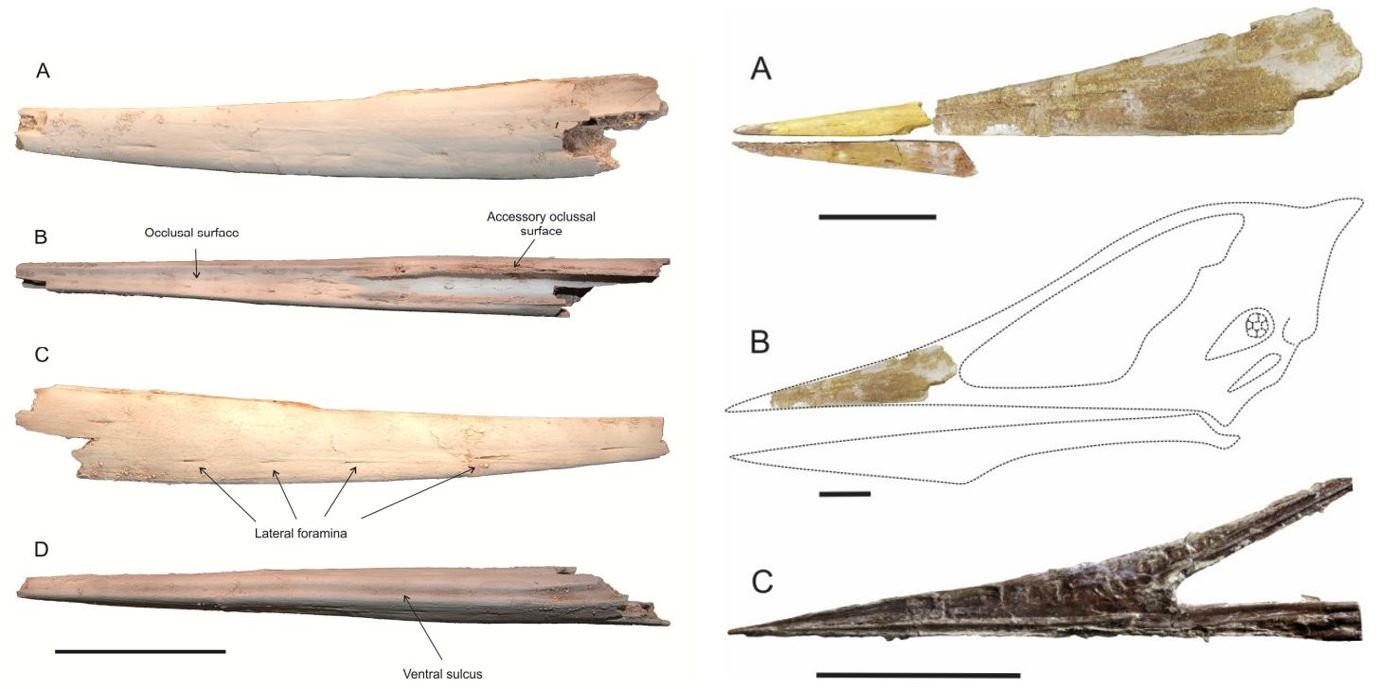

Caption: at left, the Xericeps mandible in (A) left lateral, (B) dorsal, (C) right lateral and (D) ventral views. The curvature is subtle but is there. At right: (A) Apatorhamphus parts as reconstructed, (B) as imagined using Chaoyangopterus as a template, and (C) the chaoyangopterid Jidapterus for comparison. Scale bars = 50 mm. Xericeps from Martill et al. (2018); Apatorhamphus from McPhee et al. (2020).

Xericeps curvirostris Martill et al., 2018 was named for another partial mandible from the Kem Kem, this one possessing a slight upward curvature and a groove along its midline. Martill et al. (2018) were unsure on Xericeps’s affinities within Azhdarchoidea and implied that it might represent a newly discovered lineage. However, the gently curved shape is suggestive of a chaoyangopterid identity, something supported in Pêgas et al.’s (2021) phylogenetic analysis. Andres (2021) finds it to be a thalassodromid. Another new Kem Kem taxon was named in 2020: Apatorhamphus gyrostega McPhee et al., 2020, based on a probable rostrum. This taxon is diagnosed by ‘unique combination’ of characters (something that always makes me a bit nervous), but it has a cross-sectional shape and distribution of neurovascular foramina that seems unique. On the basis of its shape, McPhee et al. (2020) suggest that it might also be a chaoyangopterid, something supported by other authors (Andres 2021, Pêgas et al. 2021).

There’s a tendency among some palaeontologists to be sceptical of the idea that more than one member of a given group might exist in a given area at a given time, despite the fact that such things are ubiquitous today. It seems plausible to me that these animals (Alanqa, Xericeps, Apatorhamphus and unnamed additional ones) are distinct, and were practising niche partitioning of the sort hypothesised elsewhere to be normal for azhdarchids (Vremir et al. 2013), though I note that the authors naming these Kem Kem taxa prefer not to cite that paper.

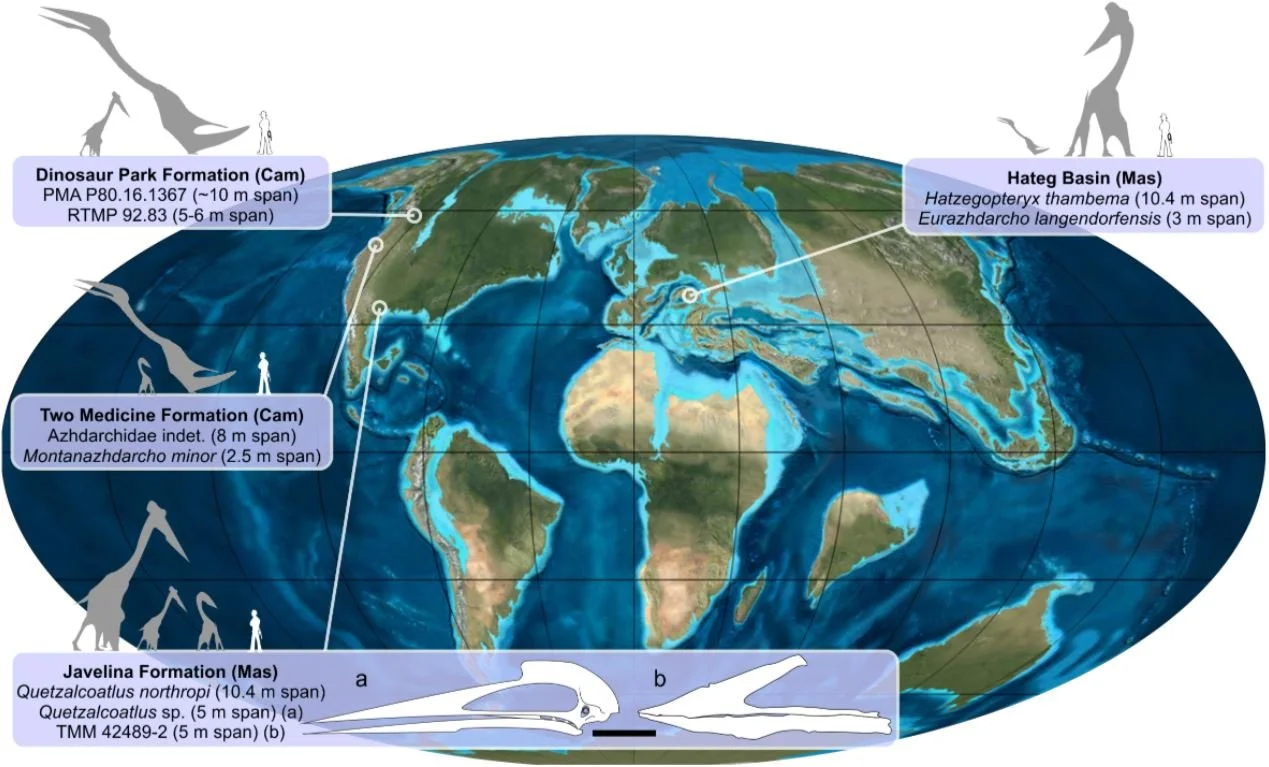

Caption: many locations that yield azhdarchids reveal one giant taxon, and two or three ‘small’ taxa. This montage – from Vremir et al. (2013) – incorporates images by Mark Witton; map by Ron Blakey, Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Inc.

Numerous additional, juvenile Kem Kem specimens have recently been reported by Smith et al. (2021). The main point of this paper is that these juveniles were occupying distinct ontogenetic stages from adults (a proposal since made for other pterosaur groups too: Naish et al. 2021) but were still considered referable to the previously named taxa, which were still regarded as distinct. Ergo, niche partitioning was present between species as well as within species. That’s a busy ecosystem, but not one any ‘busier’ than a healthy ecosystem today.

And that’s where we’ll end… talking more about chaoyangopterids than azhdarchids.

This is just a quick wrap-up of happening things in the azhdarchid world. It’s not definitive or complete. Not only have additional azhdarchid-themed discoveries (not mentioned or discussed here) been published of late, there’s also been a surge of discoveries pertaining to other azhdarchoids: the tapejarids, thalassodromids and so on. But, hey, I can’t do everything.

For previous TetZoo articles on azhdarchids and other pterosaurs, see…

Tiny pterosaurs and pac-man frogs from hell, March 2008

Daisy’s Isle of Wight Dragon and why China has what Europe does not, March 2013

In Rio for the 2013 International Symposium on Pterosaurs, May 2013

Quetzalcoatlus: the evil, pin-headed, toothy nightmare monster that wants to eat your soul, August 2013

Were azhdarchid pterosaurs really terrestrial stalkers? The evidence says yes, yes they (probably) were, December 2013

Some Azhdarchid Pterosaurs Were Robust-Necked Top-Tier Predators, February 2017

Postcranial Palaeoneurology and the Lifestyles of Pterosaurs, August 2018

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology, the TetZoo Review, September 2020

Baby Pterosaurs Were Excellent Fliers and Occupied Different Niches From Their Parents, July 2021

Refs - -

Buffetaut, E. 1999. Pterosauria from the Upper Cretaceous of Laño (Iberian Peninsula): a preliminary comparative study. Estudios del Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Alava 14 (Número especial 1), 289-294.

Buffetaut, E., Clarke, J. B. & Le Loeuff, J. 1996. A terminal Cretaceous pterosaur from the Corbières (southern France) and the problem of pterosaur extinction. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 167, 753-759.

Buffetaut, E., Grigorescu, D. & Csiki, Z. 2002. A new giant pterosaur with a robust skull from the latest Cretaceous of Romania. Naturwissenschaften 89, 180-184.

Buffetaut, E., Grigorescu, D. & Csiki, Z. 2003. Giant azhdarchid pterosaurs from the terminal Cretaceous of Translyvania (western Romania). In Buffetaut, E. & Mazin, J.-M. (eds) Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society Special Publication 217. The Geological Society of London, pp. 91-104.

Campos, H. B. N. 2021. A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation of Texas. Biologia doi: 10.1007/s11756-021-00841-7.

Company, J. Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I. & Pereda Suberbiola, X. 1999. A long-necked pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea, Azhdarchidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Valencia, Spain. Geologie en Mijnbouw 78, 319-333.

Kellner, A. W. A. & Calvo, J. O. 2017. New azhdarchoid pterosaur (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) with an unusual lower jaw from the Portezuelo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Neuquen Group, Patagonia, Argentina. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 89, 2003-2012.

Kellner, A. W. A. & Langston, W. 1996. Cranial remains of Quetzalcoatlus (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from Late Cretaceous sediments of Big Bend National Park, Texas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16, 222-231.

Lawson, D. A. 1975a. Pterosaur from the latest Cretaceous of west Texas: discovery of the largest flying creature. Science 187, 947-948.

Lawson, D. A. 1975b. Could pterosaurs fly? Science 188, 676-677.

Martill, D. M., Unwin, D. M., Ibrahim, N. & Longrich, N. 2018. A new edentulous pterosaur from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of south eastern Morocco. Cretaceous Research 84, 1-12.

Novas, F. E., Kundrát, M., Agnolín, F. L., Ezcurra, M. D., Ahlberg, P. E., Iasi, M. P., Arriagada, A. & Chafrat, P. 2012. A new large pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32, 1447-1452.

Pêgas, R. V., Holgado, B., Ortiz David, L. D., Baiano, M. A. & Costa, F. R. 2021. On the pterosaur Aerotitan sudamericanus (Neuquén Basin, Upper Cretaceous of Argentina), with comments on azhdarchoid phylogeny and jaw anatomy. Cretaceous Research 129 doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104998

Rodrigues, T., Kellner, A. W. A., Mader, B. J. & Russell, D. A. 2011. New pterosaur specimens from the Kem Kem beds (Upper Cretaceous, Cenomanian) of Morocco. Revista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 117, 149-160.

Smith, R. E., Chinsamy, A., Unwin, D. M., Ibrahim, N., Zouhri, S., Martill, D. M. 2021. Small, immature pterosaurs from the Cretaceous of Africa: implications for taphonomic bias and palaeocommunity structure in flying reptiles Cretaceous Research doi.org/10.1016/ j.cretres.2021.105061

Vullo, R., Garcia, G., Godefroit, P., Cincotta, A., Valentin, X., 2018. Mistralazhdarcho maggii, gen. et sp. nov., a new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of southeastern France. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology doi: 10.1080/02724634.2018.1502670

Wellnhofer, P. & Buffetaut, E. 1999. Pterosaur remains from the Cretaceous of Morocco. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 73, 133-142.