It’s probably – no, surely – true to say that palaeoart (aka paleoart) is more popular right now that it ever has been, a fact due in equal part to a vibrant, active community of people worldwide, to the instant, ubiquitous reach of the internet and the connectedness we feel via social media, to self-publishing and on-demand printing services, and to the excitement and discussion generated by what seems to be a never-ending stream of amazing fossil and anatomical discoveries relevant to ancient animals.

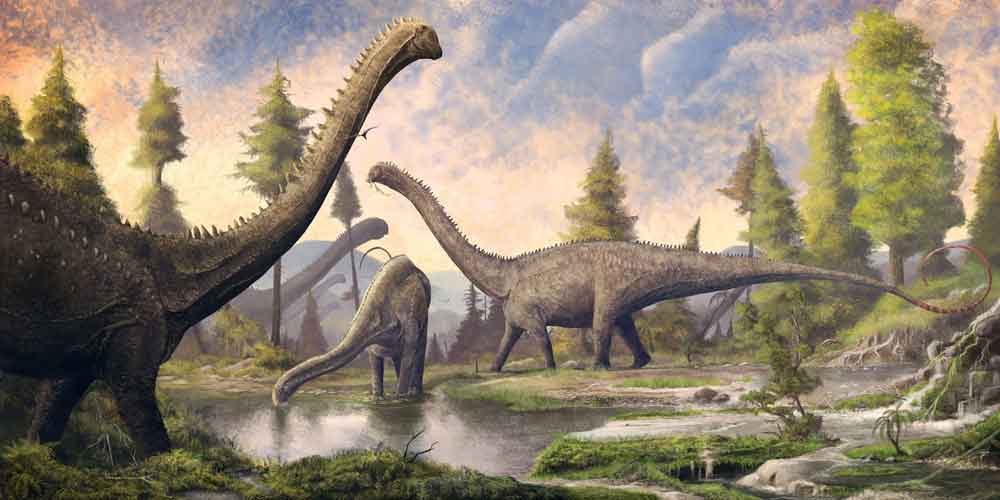

Caption: today, Mark Witton is well known for generating large-scale artworks like this one - depicting the sauropod Diplodocus, and produced to accompanying the NHM’s Dippy specimen as it tours the UK - in addition to work done to accompany press releases. Image: (c) Mark Witton.

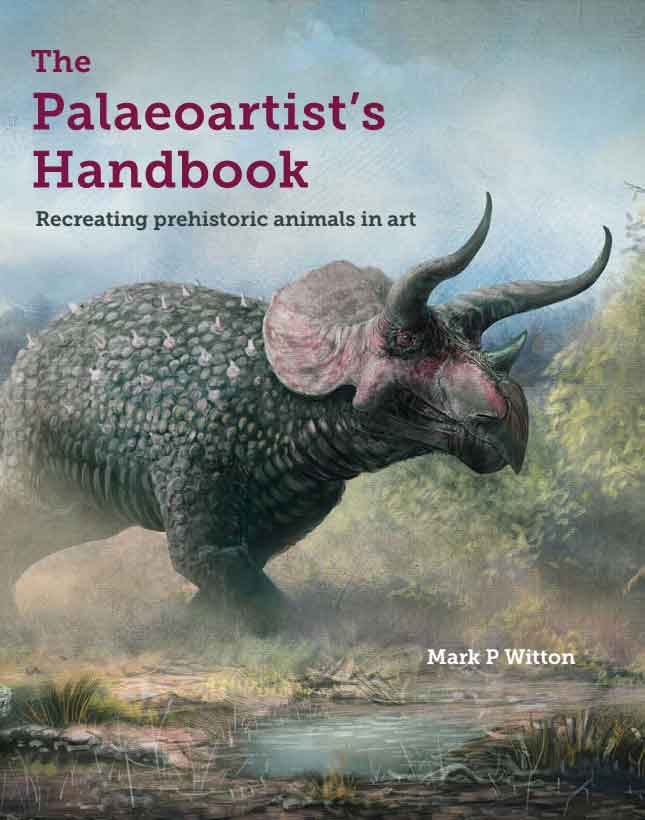

It’s no exaggeration to say that Dr Mark P. Witton is, right now, one of the world’s best known and most visible of palaeoartists; his articles and artwork are abundant online, and his work appears in many contemporary published works on prehistoric life, and in various museum installations and other displays. Combine this with the fact that he’s published a long-sought holy grail of the palaeoart canon – a palaeoart handbook – and we surely have one of the most important and worthy palaeoart-themed volumes of all time. Right? Does it deliver?

I refer to 2018’s The Palaeoartist’s Handbook, a slick, extremely affordable softback of 224 pages and extremely high production values. In response to my question above: yes, this book does deliver, and functions extremely well as a ‘handbook’ for those interested in producing palaeoart. Buy it right now if you haven’t done so already. Even those not needing or interested in Dr Witton’s advice should obtain it if they’re interested in palaeoart, since it contains stacks of invaluable review and commentary, does a great job of stating where we are with respect to what we think we know about the appearance of ancient animals, and is really well designed and densely illustrated. It’s probably the most important volume yet published on palaeoart*, and that remains true even if you dislike or disagree with the author’s contentions.

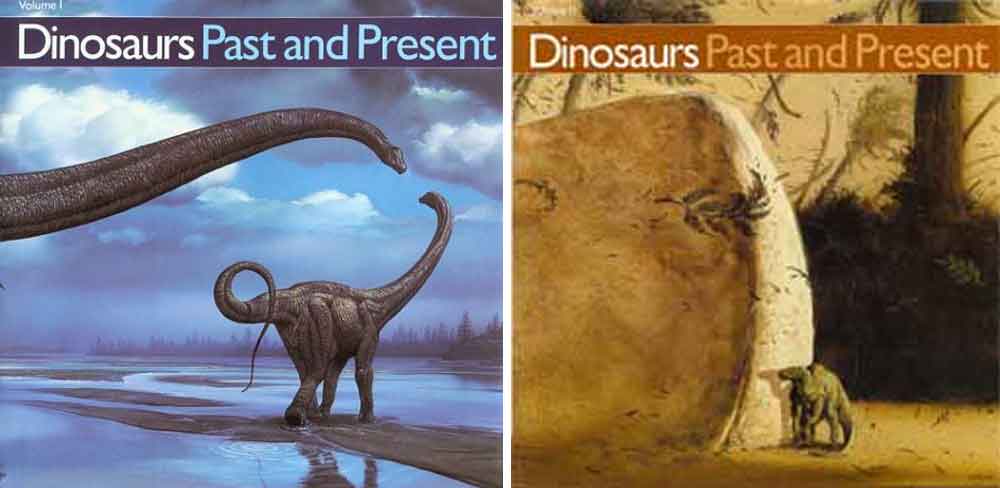

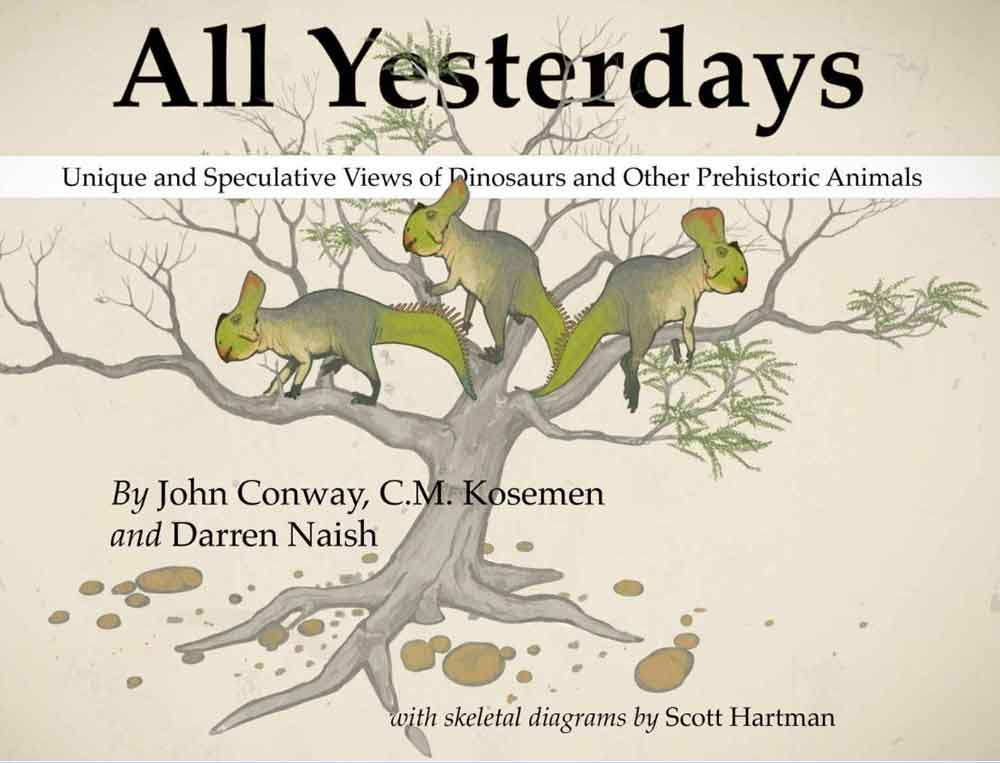

* ‘Importance’ is subjective, but the volume vies – I predict – with 2012’s All Yesterdays and volumes I and II of Dinosaurs Past and Present.

Caption: there aren’t many ‘crucial’/’must have’ volumes on palaeoart, but the Dinosaurs Past and Present volumes are among them, volume II in particular because of Greg Paul’s article (Paul 1987). Images: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press.

A disclaimer I should mention upfront is that Mark and I are long-standing friends and colleagues. I lectured to Mark when he was an undergrad, we’ve been on fieldwork together, and we’ve published several works together on pterosaurs (Witton & Naish 2008, 2015, Dyke et al. 2014, Vremir et al. 2015, Naish & Witton 2017) and palaeoart (Witton et al. 2014). These things might, in theory, mean that I’m positively biased towards his work, but in reality I think they help make me more neutral, since our good relationship means that I can say negative things (where fair and appropriate) and not be worried about being offensive. But let’s see.

Witton (2018) is extremely well designed and very attractive. It’s glossy, full colour throughout, and absolutely packed full of diagrams, photos and art. The art is not just by Mark Witton but also features images by Raven Amos, Rebecca Groom, Johan Egerkrans, Bob Nicholls, John Conway, Emily Willoughby, Julius Csotonyi and Scott Hartman. Holy crap, it’s a virtual who’s who of Early 21st Century palaeoart.

Caption: Witton (2018) includes artwork by several artists, sometimes included to depict diverse styles, compositions and approaches. This is ‘Nemegt Sunrise’ by the amazing Raven Amos (website here), and depicts the oviraptorosaur Conchoraptor with a hermit crab. Image: (c) R. Amos.

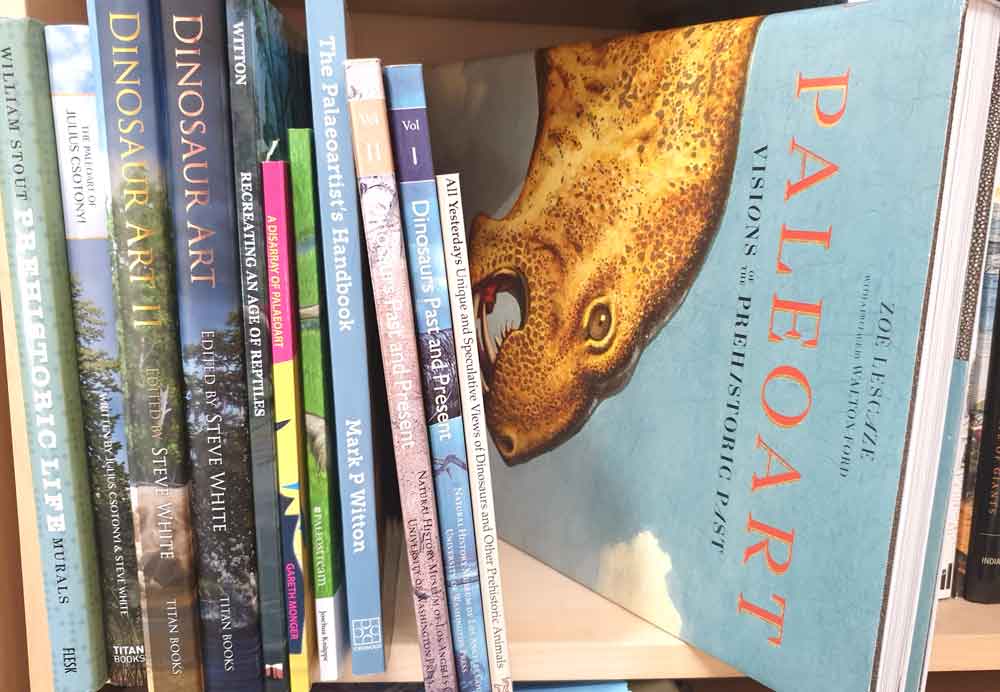

What sort of book is this? A ‘palaeoart book’ can be one of several things. It could be a compendium of historical images (like Zoë Lescaze’s gigantic, deeply idiosyncratic but invaluable 2017 Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past), it could be a bunch of new, daring stuff that makes a point of some sort (cf All Yesterdays), it could be an artist’s porfoilio or a series of portfolios (like the Dinosaur Art volumes, or The Paleoart of Julius Csotonyi), or it could be a technical volume that provides some theoretical or technical background to the field… I’m sure we’re all still waiting for ‘The Grand Handbook to Illustrating Prehistoric Life, a Rigorous How-To Guide’, hint hint.

Caption: the number of books devoted to palaeoart is growing. I think I’ve managed to keep up so far. Image: Darren Naish.

Witton (2018) is partly all of these things: the volume is fundamentally devoted to the techniques, practices and scientific processes and conventions behind the creation of palaeoart, and the case studies and targeted discussions mean that we effectively see much of Witton’s work showcased. But there’s more.

Witton (2018) begins with introductory sections on what palaeoart is and on its history. The historical chapter is quite complete and inclusive, and I’m a big fan of Witton’s take on the work of Cuvier, Hawkins at Crystal Palace and other early efforts. He’s also fair to the artists who produced work during what he terms ‘The Reformation’, some of whom (Greg Paul in particular) have had a major, lasting impact on how we imagine ancient life. The ‘palaeoart meme’ story that I’ve drawn attention to through my own research and the All Yesterdays movement bring a close to this section alongside comments on some of the amazing, exciting new developments being made in the world of soft tissues and palaeo-colour.

Caption: the Crystal Palace animals remain among the most accurate renditions of prehistoric life ever made (like all palaeoartistic reconstructions, they have to be seen as being of their time), and Mark Witton’s take on them is one I absolutely agree with. This photo of the Iguanodon pair was taken in September 2018. Image: Darren Naish.

The meat and potatoes. We then move on to the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the book: a group of chapters that discuss in great detail the process of creating palaeoart. Sections here cover how research is important and how a worker might go about doing it, how knowledge of phylogeny is integral to understanding an organism, and how artists should at least be aware of tropes and stereotypes. This book is fundamentally not a ‘rigorous how-to guide’ to all the prehistoric animals (every time I use this term I’m riffing on the title Greg Paul gave his seminal 1987 article on archosaur reconstruction), but this middle section of the book does include copious discussion of anatomy, the shapes of animals in 3D and cross-section, of musculature and posture, the importance of integument, fat and other external tissue, and so on. I should add that Chapter 9 (‘The Life Appearance of Some Fossil Animal Groups) is devoted to the probable life appearances of key tetrapod groups. Ha, take that fishes.

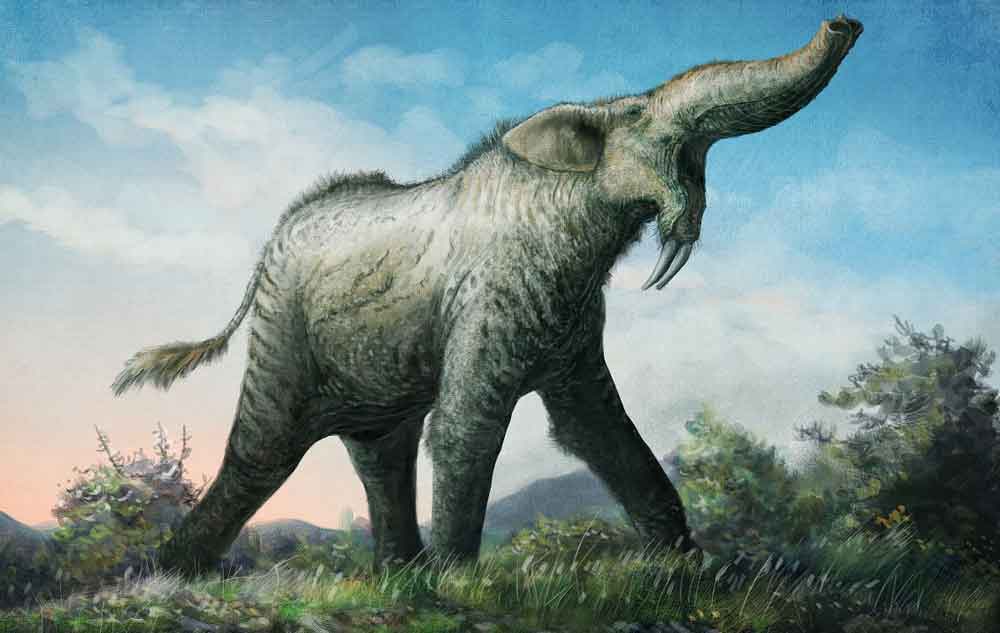

Caption: in many cases, the favoured, traditional look for a given prehistoric animal is not necessarily the one we might favour. Here’s an example: Mark has argued that a new look for the proboscidean Deinotherium - shown here - should be considered. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

These central chapters are probably the most important part of the book and will be those used most by the largest number of people. There’s a ton of information and discussion, and Mark describes in detail how he’s arrived at the conclusions he has. Readers of Mark’s blog will be familiar with some of the arguments here and might also know that much of it has never been properly published (as in, in technical papers or articles). The book is therefore especially significant as a source of primary data, though I know that efforts are underway to get at least some of it into the primary literature.

Caption: extensive sections of Witton (2018) discuss osteological correlates for external texture and other features. In some cases - like ceratopsian dinosaurs - there are many such correlates. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

How confident can we be that Mark is ‘right’ when it comes to his arguments about lips, cornified facial tissue, scalation or fuzziness on the body and so on? I think that a strong response would be that he has at least described, explained and illustrated his reasoning and it’s difficult to think that he’s ‘wrong’, two caveats being that there is – as Mark states quite clearly – still some considerable slop as goes determining the relative size of keratinous coverings (like the pads, scales and sheaths covering horns, claws and so on), and that the vagaries of taphonomy might still be cheating us out of valuable information on which archosaurs had filaments, fuzz or feathers. Yes, I still think that big tyrannosaurs could have been fuzzy and that we aren’t picking this up because the fossils concerned aren’t preserved in the ideal sedimentological regimes.

Speculation and the All Yesterdays Movement. The main message here is that while some speculation always has to be included in palaeoartistic reconstructions, there’s a lot of stuff that’s knowable, or potentially knowable, and informed by actual anatomical data. This is increasingly the case even for colour and pattern (caveat: we still only have data on some infinitesimally tiny percentage of extinct animals). The door is not open for any possibility, and artists who wish to be seen as doing work that’s scientifically credible have to take into account data derived from fossils as well as ‘rules’ (or guidelines) gleaned from living animals. However…

Caption: Conway et al.’s 2012 All Yesterdays has changed the way many people approach palaeoart… but is this for better, or for worse? Image: Conway et al. (2012).

A valid, controversial and timely point concerns just how much speculation is permissible in palaeoart. This is something I feel especially connected to given the impact of my 2012 book – co-authored with John Conway and C. M. Kosemen – All Yesterdays (Conway et al. 2012) and the subsequent ‘All Yesterdays Movement’, which is hated by some but loved by others. Mark’s take on what happened post-AY is that a lot of AY-inspired artwork has failed to appreciate the nuance of the original work, and that AY was (wrongly) taken by some as a green light to go nuts and do whatever, the results being misguided and likely wrong.

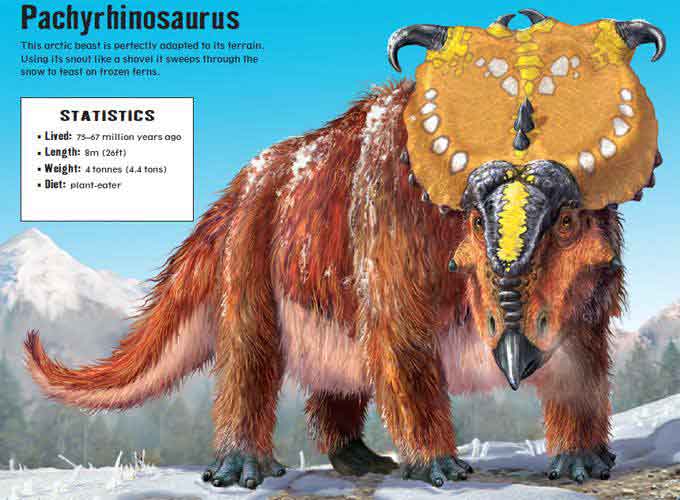

Caption: Mark has indulged in some speculation himself (here: shaggy-coated pachyrhinosaurs), and it’s down to opinion as to whether this is as extreme as anything depicted in All Yesterdays. Image: Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

Caption: it would be wrong to avoid bringing attention to Franco Tempesta’s woolly, cold-adapted pachyrhinosaur, very obviously inspired by Mark Witton’s, and appearing in the 2016 Usborne book Build Your Own DInosaurs Sticker Book. I was consultant, but I’m sure that that’s coincidental. Image: (c) Franco Tempesta/Usborne.

I agree… if we’re talking about artworks that aim to reflect possible realities. A nuance to the nuance of AY is that there exists a small contradiction in the aims of its creators. Yes, we argued that there are many potentially valid, scientifically defensible possibilities that hadn’t or haven’t been sufficiently explored in pre-AY palaeoart, but we did also promote the idea that people might explore other possibilities – even those weird or dumb or wrong – purely for the sake of artistic expression. That this view is canonical in the AYverse is demonstrated by the inclusion in the sequential All Your Yesterdays of retrosaurs that are absolutely contradicted by data but still fun from an artistic take. In other words, not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically defensible. The takehome – post-AY – is that people need to say what they’re aiming to depict: a random fancy or a serious proposal?

Caption: not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically responsible and potentially realistic, some of it is deliberately whimsical and fanciful. Exhibit A: the wonder that is Spinofaaras vulgaris, a creature that now has an internet life of its own. Image: (c) Chris Masna (original here).

Anyway, returning to the contents of Witton (2018), this main section wraps up with some thoughts on how landscapes are created, and how composition and mood can be formed. Discussing environments and landscapes involves science – geology, geomorphology and palaeoclimate, among other things – and this is Witton’s main strength, but I also found his take on composition, stylistic choices and other matters of artistic style compelling…. speaking as someone who lacks artistic training and expertise, that is. The volume ends with a chapter on the professional side of palaeoart.

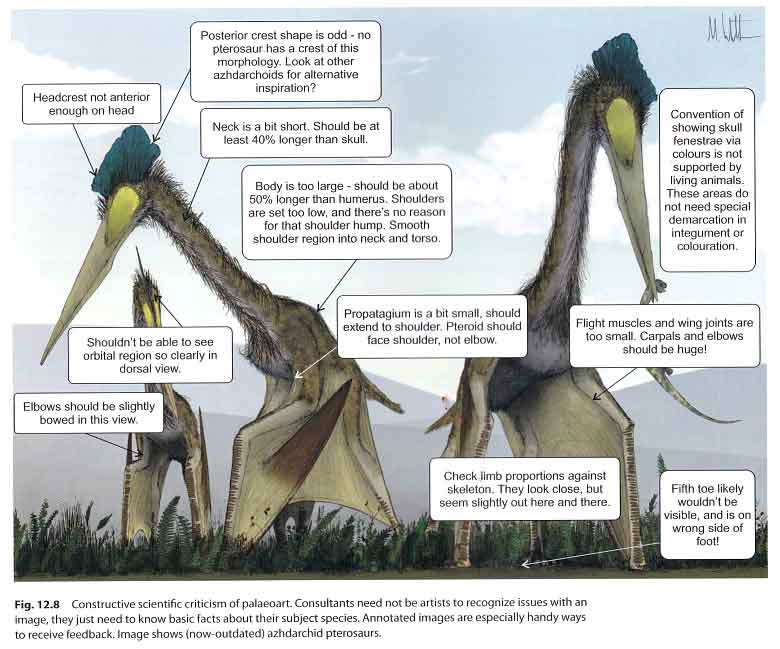

Caption: feedback and criticism is crucial, but it can be difficult to know what to say to artists when you aren’t one yourself. In this section of the book, Mark provides advice, using his 2008 azhdarchid image as a piece that might benefit from constructive criticism. This piece accompanied the Witton & Naish (2008) PLoS paper on azhdarchids. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

On the negative side of things… I find the editing sloppy in places and think that the prose could have been tightened here and there. There are also a few turns of phrase that I found awkward, weird or (sorry) terrible, top of the list being the reference to “palaeontologists with the mightiest beards” (p. 38). On technical aspects, I’m a bit confused by Mark’s use of ‘reptile’ in the old, paraphyletic sense (in a volume otherwise using modern phylogenetic nomenclature, wouldn’t it make sense to use Reptilia for the lizard + turtle + croc clade, and not to use it for a paraphyletic assemblage that excludes birds?). Panoplosaurus is wrongly called an ankylosaurid (p. 125), and isn’t Deinotherium a deinotheriid, not a deinotherid? These are minor, piffling, trivial things that I only state here because I have nowhere else to put them.

Caption: the book is just full of spectacular imagery like this, much of which hasn’t appeared in print before. This image depicts the azhdarchoid pterosaur Thalassodromeus. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

All in all, The Palaeoartist’s Handbook is an excellent, beautifully produced, well crafted book which contains a wealth of information on the life appearance of extinct animals and how we might imagine them as living things, and it’s phenomenally good on the workings of palaeoart more generally. It should have broader appeal than to the palaeoart fraternity alone, and I think that anyone seriously interested in prehistoric animals or even in the history of art or the way people have imagined the past should obtain it too. For now, Witton (2018) is – mission fulfilled – THE palaeoartist’s handbook indeed.

Mark P. Witton. 2018. The Palaeoartist’s Handbook: Recreating Prehistoric Animals in Art. The Crowood Press, Marlborough (UK), 224 pp, softback, index, refs, ISBN 978-1-78500-461-2. Here on amazon. Here on amazon.co.uk.

For previous TetZoo articles on palaeoart and Wittoniana (the ver 2 and ver 3 ones have been ruined by removal of images), see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012 (but all images now missing)

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012 (but all images now missing)

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014 (but all images now missing)

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

The Natural History Museum at South Kensington, November 2016

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 1, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 2, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 3, June 2018

Dinosaurs in the Wild: An Inside View, July 2018

Recollections of Dinosaurs Past and Present, the 1980s Exhibition, February 2019

Refs - -

Paul, G. S. 1987. The science and art of restoring the life appearance of dinosaurs and their relatives - a rigorous how-to guide. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present Vol. II. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and London), pp. 4-49.