A few authors would have it that there are too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!): that the rich sauropod assemblage of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the continental western interior of the USA simply contains too many species, and that we need to wield the synonymy hammer and whack them down to some lower number. In this article and those that follow it, I’m going to argue that this view is naïve and misguided. You’ll need to have read Part 1 – the introduction – to make sense of what follows here. Ok, to business…

Caption: Apatosaurus louisae on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh. This is CM 3018, the holotype of the species, and one of the best described, most thoroughly known of all apatosaurine diplodocids. This is just one of around 17 diplodocid species recognised from the Morrison Formation. Image: Tadek Kurpaski, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Those comparisons with mammals are erroneous. Prothero (2019) said TMDD!, in part because he’s aware of research whereby supposedly contemporaneous megamammal species have – over the years, in work including that of his own – been shown to be radically oversplit*. In other words, what were initially thought to be some or many distinct species and genera eventually turned out to be some much lower number. He pointed to Osborn’s brontotheres, to North American hyracodontid and rhinocerotid rhinos, and to the Eurasian indricotheres as cases where good, careful work has shown how an initially high number of species and genera were reduced to something more biologically reasonable. Why is rhino and brontothere and indricothere taxonomy relevant to sauropod diversity? Prothero’s argument goes like this: if fossil megamammals were oversplit, surely Morrison sauropods might be too.

* Meaning that what were initially identified as some or many species were actually just representatives of a single taxon which had been incorrectly ‘split’ into those some or many. The process in which this happens is termed taxonomic inflation and it plagues studies on biodiversity.

Caption: the amazing skull of Paraceratherium transouralicum (this is the specimen on show at the Cambridge Museum of Zoology, a cast of Hsanda Gol specimen AMNH 18650). Prior to the 1980s, Paraceratherium was oversplit into several genera. Is this relevant to the TMDD contention? Image: Darren Naish.

The problem is that none of this is directly applicable to the fact that Morrison Formation sauropods were highly diverse.

For starters, some of these oversplit mammal taxa were obviously oversplit: the multiple brontothere species and genera recognised by Henry Fairfield Osborn during the 1920s and 30s and by Granger and Gregory in 1943, for example, were widely regarded as mostly invalid by every specialist who looked at them within the past five decades, and it would be wrong to imply that we’ve only just tidied up the mess here in the 21st century. Scott (1941) rejected Osborn’s oversplit taxonomy entirely, and Stanley (1973) said “Osborn’s species-level taxonomy is in need of considerable revision” (p. 447). An essentially modern view on Osborn’s oversplit brontotheres had emerged by the time Bryn Mader was writing about them in the late 1980s and 90s (e.g., Mader 1998). They were, of course, further tidied up in the definitive work of Matthew Mihlbachler (2008). Prothero (2019) is wrong, by the way, in saying that “only Megacerops coloradensis is a valid name for the incredible array of different-looking specimens from the late Eocene” (p. 110), since M. kuwagatarhinus is also currently recognised. It was sympatric with M. coloradensis.

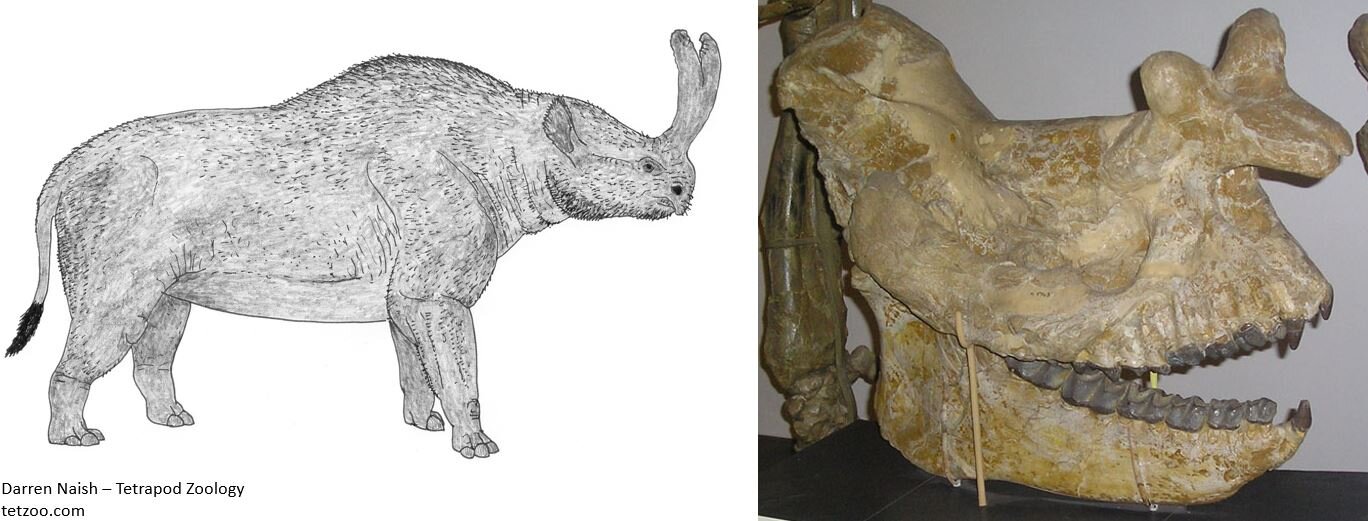

Caption: the best known brontotheres were very large herbivores (larger than the biggest living rhinos) with bony nasal horns. One of the last brontotheres - Megacerops - is highly variable in horn form, and this previously led to gross taxonomic inflation. The reconstruction at left was produced for my in-prep textbook. The skull at right is on show at the Natural History Museum, London. Images: Darren Naish.

On the North American rhinos, Prothero (1996, 1998a, b, 2005) established that Hyracodon, Subhyracodon and Trigonias were horrendously oversplit by those who published on these animals between the 1800s and 1950s; his measurements on their cheek teeth showed that diversity had been over-stated and misunderstood. But a check of the literature published from the 1970s onwards shows that interested researchers were well aware that many of the species and genera named and retained by their predecessors were problematic and due for revision: Prothero (2005) said of Loris Russell’s work from the early 1980s, for example, that “Like previous workers, he was confused over the persistence of invalid concepts … and the scrambled taxonomy” (p. 24). Again, we’re talking about a modern view emerging during the 1980s and 90s, rather than within the last couple of years. Furthermore, it was ‘easy’ to demonstrate the oversplit nature of these animals by running basic tests on their measurements (Prothero 1996, 1998a, b, 2005). Remember that last point, it’s relevant to the Morrison sauropods.

Caption: three rhino taxa which underwent some fair degree of taxonomic revision during the 1980s and 90s. 1. The gigantic Eurasian hyracodontid Paraceratherium. 2. The North American hornless rhinocerotid Trigonias. 3. The North American elasmotheriine rhnocerotid Subhyracodon. These are among a huge number of rhinos I’ve reconstructed for the in-prep textbook. Images: Darren Naish.

Finally, what about the indricotheres of the Oligocene? Once upon a time, palaeontologists recognised a whole list of supposedly distinct indricotheres. The first to be named was Paraceratherium, but then there was Baluchitherium, Indricotherium, Aralotherium, Pristinotherium, Tsungaritherium and so on*. By the 1980s it was obvious that this was mostly wrong, and that none of these animals were distinct enough to warrant separation (though read on). Accordingly, Lucas & Sobus (1989) sank them all into the one genus – or did they, read on – the correct name for which is Paraceratherium. As part of his TMDD argument, Prothero (2019) pointed to the fact that what were once regarded as a list of many indricothere taxa are actually “all one genus and species” (p. 110). But… that’s not right.

* Following Prothero, I initially listed Caucasotherium within this lot but I’ve since learnt that a 2000 study showed it to be synonymous with the pig Kubanochoerus. See the comments.

Caption: Don Prothero’s 2013 book on indricotheres. I’m pretty confident that the look advocated in this book for indricotheres - in which they’re said to have a massive upper lip and elephant-like, flappy ears - is partly bogus, especially the thing about the ears (Mark Witton covers this issue in more depth here). The art - by the excellent Carl Buell - is very nice though.

It’s certainly agreed today that the multi-genus model for indricotheres is invalid, but this doesn’t mean that they all form the same one taxon. For starters, there’s doubt over the status of the gigantic Chinese species Dzungariotherium orgosense. In his book on indricotheres (which includes a new test of Lucas & Sobus’s (1989) argument), Prothero (2013) remained uncertain about its status and said that it might still be worth recognising as a distinct genus-level taxon, an opinion that seems mostly adopted by perissodactyl specialists today. Secondly, even the most conservative take on these animals concludes that there are still several distinct species. They are not “all one genus and species” (Prothero 2019, p. 110)! According to Prothero (2013), P. bugtiense, P. transouralicum and P. prohorovi are all valid in addition to Dzungariotherium orgosense. Furthermore, another species – P. huangheense Li et al., 2017 – has been recognised since and does look to be distinct (Li et al. 2017). In other words, we still – even today – recognise a bunch of indricothere species that occurred across a continent, over a period of about 15 million years (Prothero 2013).

Caption: the days of recognising multiple indricothere genera are gone, but this doesn’t mean - contra Prothero (2019) - that there’s only one species! This figure, showing the jaws of five species, comes from Li et al. (2017).

The takehome. Prothero’s main argument was ‘Cenozoic megamammals have proved oversplit, therefore Morrison sauropods could be too’. But…

(1) Experts on the respective mammal groups were – from the 1970s and 80s onwards – almost all in agreement that the groups concerned were oversplit. Contrast this with the sauropod situation; respective experts have looked and looked and looked at these animals again and again and do not see an issue with the existing taxonomy, as weird as it may seem to have so many contemporary giants. Indeed, they keep naming new ones, not synonymising old ones. We’ll return in a later article to the issue of experts and the way in which they’ve handled Morrison sauropod taxonomy.

(2) Once respective experts began applying very basic tests to the mammals concerned (morphometrics based on tooth measurements, for example), taxonomic revisions were swift and merciless. The same sorts of tests have been applied to sauropods – McIntosh (1990) did this for vertebrae, limb bones and limb girdles of Morrison sauropods (see also McIntosh (2005) and Wilhite (2005)), and Bonnan (2004) did it for Morrison sauropod limb bones, for example – and the respective species do not collapse into synonymy.

(3) The implication that those megamammal species and genera once considered very high in diversity are now all known to be ultra-low in diversity isn’t accurate, nor is this a fair comparison if we’re pitting megamammal diversity against that of Morrison sauropods. Paraceratherium isn’t a sole standalone, for starters (contra Prothero 2019), but a cluster of species. And those North American Paleogene faunas in which the two Megacerops species were found were also inhabited by several rhino species (belonging to various hyracodontid, rhinocerotid and amynodontid lineage), by the entelodont Archaeotherium, and by both anthracotheriine and bothriodontine anthracotheres. While it might be true that we recognise far fewer brontotheres and rhinos today that we did prior to the revisions of the 1980s, 90s and beyond, the species we do recognise are still members of multi-species faunas where there are abundant contemporaneous megamammals. This point – that pre-Holocene mammal assemblages contained abundant species and hence were more like Mesozoic dinosaur assemblages than Holocene mammal assemblages – is a non-trivial one, and we’ll be coming back to it later.

In the next article in this series, we’ll be looking at mammals again, this time at mammals of a more modern sort.

For the previous article in this series, see…

For previous TetZoo articles on sauropods, brontotheres and related issues (linking where possible to wayback machine versions), see…

Biggest…. sauropod…. ever (part…. I), January 2007

Biggest sauropod ever (part…. II), January 2007

The hands of sauropods: horseshoes, spiky columns, stumps and banana shapes, October 2008

Thunder beasts in pictures, March 2009

Thunder beasts of New York, March 2009

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures, May 2009

Paul Brinkman’s The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush, March 2011

The sauropod viviparity meme, May 2011

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part I), December 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part II), January 2012

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, February 2012

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012), November 2012

That Brontosaurus Thing, April 2015

10 Long, Happy Years of Xenoposeidon, November 2017

The Life Appearance of Sauropod Dinosaurs, January 2019

Refs - -

Bonnan, M. F. 2004. Morphometric analysis of humerus and femur shape in Morrison sauropods: implications for functional morphology and paleobiology. Paleobiology 30, 444-470.

Li, Y.-X., Zhang, Y.-X., Li, J., Li, Z.-C. & Xie, K. 2017. New fossils of paraceratheres (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) from the Early Oligocene of the Lanzhou Basin, Gansu Province, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 56, 367-381.

Lucas, S. G. & Sobus, J. C. 1989. The systematics of indricotheres. In Prothero, D. R. & Schoch, R. M. (eds) The Evolution of Perissodactyls. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 358-378.

Mader, B. J. 1998. Brontotheriidae. In Janis, C. M., Scott, K. M. & Jacobs, L. L. (eds) Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America. Volume 1: Terrestrial Carnivores, Ungulates, and Ungulatelike Mammals. Cambridge University Press, pp. 525-536.

McIntosh, J. S. 1990. Species determination in sauropod dinosaurs with tentative suggestions for their classification. In Carpenter, K. & Currie, P. J. (eds) Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge), pp. 53-69.

McIntosh, J. S. 2005. The genus Barosaurus Marsh (Sauropoda, Diplodocidae). In Tidwell, V. & Carpenter, K. (eds) Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press (Bloomington & Indianapolis), pp. 38-77.

Mihlbachler, M. C. 2008. Species taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of the Brontotheriidae (Mammalia: Perissodactyla). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 311, 1-475.

Prothero, D. R. 1996. Hyracodontidae. In Prothero, D. R. & Emry, R. J. (eds) Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution. Paleontological Society Short Courses in Paleontology 7, 238-270.

Prothero, D. R. 1998a. Hyracodontidae. In Janis, C. M., Scott, K. M. & Jacobs, L. L. (eds) Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America. Volume 1: Terrestrial Carnivores, Ungulates, and Ungulatelike Mammals. Cambridge University Press, pp. 589-594.

Prothero, D. R. 1998b. Rhinocerotidae. In Janis, C. M., Scott, K. M. & Jacobs, L. L. (eds) Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America. Volume 1: Terrestrial Carnivores, Ungulates, and Ungulatelike Mammals. Cambridge University Press, pp. 595-605.

Prothero, D. R. 2005. The Evolution of North American Rhinoceroses. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Scott, W. B. 1941. The mammalian fauna of the White River Oligocene. Part 5. Perissodactyla. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 28, 747-980.

Stanley, S. M. 1974. Relative growth of the titanothere horn: a new approach to an old problem. Evolution 28, 447-457.

Wilhite, D. R. 2005. Variation in the appendicular skeleton of North American sauropod dinosaurs: taxonomic implications. In Tidwell, V. & Carpenter, K. (eds) Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press (Bloomington & Indianapolis), pp. 268-301.