Long-time readers of TetZoo – those who’ve been visiting since the ver 2, or ScienceBlogs, years – might remember the article on sleep behaviour and sleep postures, published way back in September 2008 (that original article is here). I don’t want to get into the habit of republishing old stuff ‘from the archives’ here at ver 4, partly because I have an essentially infinite amount of new stuff I want to get online but also because the old stuff needs to be published in book form (yeah… how’s it going with that? Not well).

Caption: the sleeping behaviour of some animals is quite familiar to us. Other animals? — less so. Images: Malcolm Daniel, used with permission (left), Darren Naish (right).

Anyway, the sleep article is sufficiently useful that it needs to be republished, especially so given that hosting issues at ScienceBlogs mean that all my old articles have been stripped of their images, sigh. Pre-amble done, let’s get to it. I’ve augmented and expanded the original text in view of new things I’ve learnt and new studies I’ve been made aware of.

Caption: some sort of bear-like creature, asleep. Image: Darren Naish.

For a long time now I have been, shall we say, gently encouraged by two of my friends to write about a subject that is both familiar, and yet also strangely alien and poorly understood. Sleep behaviour. We still know comparatively little about this subject: not only about the big stuff like its function, but even about its distribution within animals. I am not, by the way, about to tackle the big questions about sleep, nor am I going to discuss the different types of sleep (e.g., REM vs NREM sleep) and on how they differ from creature to creature. Instead I’m interested in the more superficial stuff, like how and where animals sleep, and the postures they adopt.

Caption: John Conway’s sleeping Tyrannosaurus, from All Yesterdays. We don’t know how non-bird dinosaurs slept (though several fossils give us a good idea for some groups at least). We can, nevertheless, make lots of inferences based on the behaviour of living animals. Image: John Conway/All Yesterdays.

What we do know about sleep is scattered widely in the literature and it isn’t easy to obtain any sort of review of the subject. A chapter in an academic book – Lee-Chiong’s 2006. Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook – does include a good overview of sleep behaviour in non-human animals (Lee-Chiong 2006, Lesku et al. 2006), but the google books version (the only one I’ve seen) doesn’t include the chapter in entirety, as per usual. There is at least one book devoted to sleep in non-human aniamls: Maurice Burton’s Sleep and Hibernation in the Animal World (Odhams Books, 1969), one of twelve books written for the Animal World in Colour series. Burton is well known for amassing large amounts of anecdotal data on the natural world (he also wrote books covering cryptozoology and the emotional lives of animals), and while the books in the Animal World in Colour series include a lot of often bizarre and fascinating information, they’re completely unreferenced and at least some of the content looks apocryphal and difficult to be confident about. Despite these problems I’ve borrowed heavily from his book on sleep here.

Caption: Maurice Burton’s Sleep and Hibernation in the Animal World, part of the Animal World in Colour series, shown at left at their home in the TetZoo library (there are 12 titles in total, so I’m still missing three). Images: Darren Naish.

Needless to say, I’m only going to be looking here at sleep in tetrapods, though where relevant I will mention other animals. The first thing to say is that some animals get by with very little sleep, or in fact may even go without sleep entirely. Among vertebrates, all identified non-sleeping taxa are fish (Kavanau 1998). The species concerned have little in common (they include blind cave-dwellers, various sharks including some triakids, lamnids, hammerheads and sevengills, and mackerels and scombrids), but all have lifestyles where “visual input is greatly reduced or absent during lengthy periods”, where “schooling greatly reduces needs for sensory information, particularly visual'” or where the animals lead a “comparatively routine existence in essentially featureless, open waters” (Kavanau 1998, p. 269).

Caption: fishes. I ain’t sayin’ nothing, apart from what I just said. Image: Darren Naish.

Reduced or delayed sleep. Perhaps because no tetrapod lives in this way, it seems that all indulge in at least some sleep activity, and indeed will die if deprived of sleep for prolonged periods (Rechtschaffen et al. 1983). Having said that, some tetrapods sleep very little, or go for comparatively long periods with little to no sleep. One proposal for the function of sleep is that it gives animals the chance to save energy when remaining active is unproductive. Within this model, animals might be able to forego sleep if remaining active is productive, as would be the case during periods when an otherwise rare food source is suddenly in plentiful supply, during migrations, or during a brief breeding season when wakefulness guarantees successful mating.

On that last point, male Pectoral sandpipers Calidris melanotos are known to reduce their time spent sleeping during their annual lekking period, those males that sleep the least being the ones that succeed in having the highest number of copulations (Lesku et al. 2012). In other words, sexual selection has led to a reduction in sleep. We might honestly consider whether this is applicable to other animals that don’t sleep as much or as often as expected, our own species included (read on).

Caption: Pectoral sandpiper, the most wideawake of the waders… pending future discoveries. Image: Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren, wikipedia, CC BY 2.0 (original here).

The animals best known for reducing or delaying their sleep are seabirds. Some species are on the wing for weeks, months and supposedly even years at a time and appear to be constantly active. Yes, years at a time. Couzens (2008) writes of Sooty terns Onychoprion fuscata staying aloft for as much as four or five years as juveniles and that “Nobody has ever seen a healthy juvenile bird at rest, whether on a beach, rock, buoy or on any floating object” and “The thought of keeping aloft for four or more years is mind-boggling to us. How do the birds sleep? Why don’t they tire? What about storms?” (p. 83).

It has been suggested that such birds might sleep on the wing – this has so far been confirmed for frigatebirds using electroencephalograms and GPS loggers (Rattenborg et al. 2016) – but it’s considered equally plausible that they simply delay their sleep to some point later in life. And having mentioned ‘sleep on the wing’, while it’s well known that swifts sleep in flight, the evidence for this (which essentially consists of observations of swifts seen decreasing in altitude during the early hours of the morning) is poor and we still require detailed studies (Rattenborg 2006).

Caption: I’ve seen hundreds of frigatebirds while in South America - this is my best photo of one - but I don’t remember noticing that any were asleep. Image: Darren Naish.

Cetaceans – or, killer whales and bottlenose dolphins at least – go for the first month or two of life without sleeping, and their accompanying mothers also go without sleep during this period (Lyamin et al. 2005). The possibility exists that very short bursts of shallow sleep might have occurred in the animals under study, but any such bursts (which weren’t detected) could not have exceeded 30 seconds in duration (Lyamin et al. 2005). Quite how these animals can go without proper sleep during a period coinciding with important events in growth and development is unknown but it’s consistent with the idea that sleep can be dispensed with “when ecological demands favour wakefulness” (Lesku et al. 2012, p. 1654).

Caption: sleeping cow, photographed in India, in a pose not considered that typical for bovids or artiodactyls in general. It’s not that uncommon if you look at sufficient numbers of sleeping cows, however. Image: the original source has disappeared from the internet!

Some ruminants seem to engage in very little sleep. This might be because they need to remain constantly alert for predators, but it might also be because their biology requires a virtually continuous cycle of eating and ruminating. Burton (1969) wrote of observations made on goats which suggest that, during a rest period that lasts about 8 hours, they never really relax fully, and it’s even stated here and there that some ruminants (like cattle) sleep with their eyes open. Ruminants do sleep with their eyes closed at least sometimes however, as verified by the sleeping cow shown above. Passive stay apparatus (special locking mechanisms in the limbs) mean that some hoofed mammals can remain standing virtually indefinitely, and such mammals (which include deer, rhinos and horses) are therefore capable of sleeping while standing. Having said that, they will still lie down to rest when they want to. I photographed the donkey shown here as I initially thought it was dead.

Caption: sleeping domestic donkey, reclining on its side. The animal stayed like this for some time (an hour at least). Image: Darren Naish.

Finally, also worth noting here is that humans actually sleep way less than we ‘should’, relative to other primates. For whatever reason, we’ve managed to reduce the amount of sleep we should have according to our body size, perhaps by as much as 50%. I take seriously the possibility that we’re similar to Pectoral sandpipers, and that sleep reduction is driven by sexual selection (this is the get lucky hypothesis). Other possibilities have equally good explanatory power though. A whole article could be written on human sleep behaviour…

Caption: human sleep behaviour is interesting - we’re unusual, relative to other primates, in several respects. Sleeping in the snow is not usually advised though. Image: Darren Naish.

Giraffes and elephants. It used to be thought that the biggest extant hoofed mammals – giraffes – didn’t sleep at all, but this was shown to be incorrect by Grzimek (1956) who demonstrated that adult giraffes slept recumbently on the ground for short periods (2.5-6 minutes), resting the head on the hindquarters or ground and holding the neck in an arced posture. This posture is not unique to giraffes but is also practised by okapis and some bovids. The sleep behaviour of giraffes was looked at in detail by Tobler & Schwierin (1996) who showed that giraffes slept both while standing and while recumbent for a total of 4.6 hours per 24 hours.

Caption: here’s a baby giraffe in the so-called ‘kettle posture’ typical for sleeping giraffes (though they can sleep in other poses too). This image is all over the internet and I haven’t succeeded in finding who should be credited for the original.

Evidently little known is that elephants lie down on the ground to sleep properly: even today it seems widely thought that elephants ‘crush themselves under their own weight’ if they lie down, but this just isn’t true. In the wild, elephants sleep for 1-4.5 hours (per 24) in a recumbent position, with individuals showing preferences for sleeping on their left or right sides. Tobler (1992) reported that captive Asian elephants slept in a recumbent position for an average of 72 minutes a night. Elephants have been photographed propping themselves up against termite mounds and other structures when lying down to sleep, and in captivity they have been reported to construct pillows from straw. The photo below shows a sleeping captive Asian elephant Elephus maximus, and for images of African elephants sleeping recumbently in the wild go here.

Caption: sleeping Asian elephant in captivity. Image: Fruggo, CC BY 1.0, wikipedia (original here).

Birds large and small, on the ground. Large birds are also known to recline on the ground for at least short periods. Burton (1969) reported how a scientist at Frankfurt Zoo monitored the sleep behaviour of ostriches: for 7-8 hours per night, they slept lightly with the neck erect. But for an average of 9 minutes each night they would lie on their sides, stretch their necks and legs out on the ground, and sleep deeply, during which time they couldn’t be roused by lights or noises (except the very loudest noises). Emus, incidentally, are said to sleep deeply with the head and neck resting on the back, rather than lying on the ground.

Caption: a Ptarmigan Lagopus mutus in its snow burrow. This illustration - by Ad Cameron - is meant to show the bird sleeping in its burrow, but a bird properly using such a refuge would be concealed from outside view. Image: Ad Cameron, in Perrins (1992).

Moving to other birds, terrestrial, ground-foraging birds like pheasants roost on the ground or in the branches of trees, and simply huddle up and tuck in their appendages. Grouse living in snowy places construct snow burrows and have a set of adaptations that make them good at constructing these shelters (a topic I aim to cover in the near future), and various passerines of snowy environments – including kinglets, finches, buntings and tits – also build snow shelters and sleep in them (e.g., Sulkava 1969, Novikov 1972).

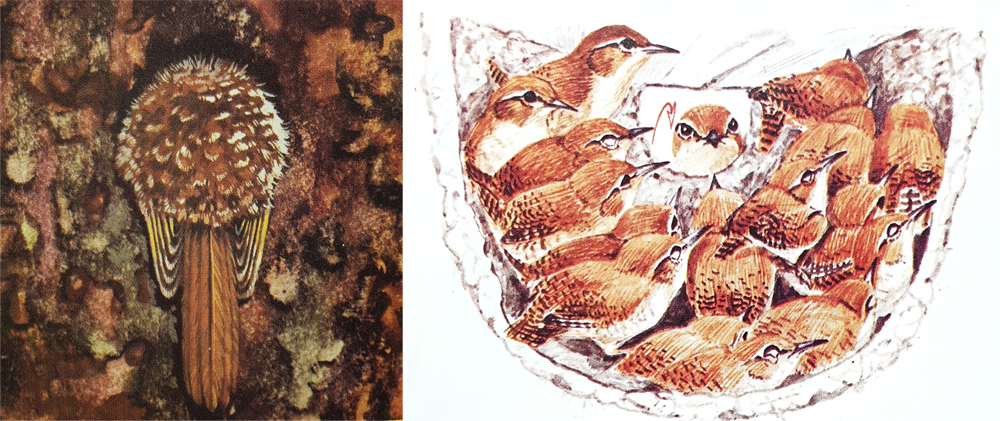

Caption: at left, a tree-creeper (Certhia), sleeping while partially tucked up inside a cavity in a tree. At right, a rendition of one of those famous cases in which large numbers of wrens (Troglodytes troglodytes) - more than 40 or 50 - have been discovered packed inside the same nest, huddled together for warmth. In this case, the wrens are using an empty House martin Delichon urbicum nest. Images: Burton (1969), Ad Cameron, in Perrins (1992).

Small birds in cavities and thick foliage. Many small, tree-dwelling birds don’t sit out on branches during the night (though some do, see below), but secrete themselves into small crevices, cavities or thick vegetation. I once discovered a Blue tit Cyanistes caeruleus tucked deep within a crevice in the bark of a tree, only its tail tip sticking out. Small birds of many sorts do seem to rely on dense foliage as a night-time refuge. Remember this next time you unnecessarily tear down the ivy from a tree or fence.

Caption: this photo is pretty terrible but it’s the only one I have of small birds (in this case: House sparrows Passer domesticus) sleeping in a concealed spot, tucked up beneath a roof and perched on tangled vegetation. It was taken in May 2011 and is partly so bad because I didn’t want to disturb the birds. Image: Darren Naish.

Some passerines, including wrens, weavers and bush-tits, form large huddles within cavities (Perrins 1992). Burton (1969) wrote that birds which climb vertically on substrates, like nuthatches and treecreepers, also sleep in vertical postures, with nuthatches resting head-down and treecreepers resting head-up. Woodpeckers are also reported to sleep clinging vertically to vertical trunks (Perrins 1992). A few passerine species have been reported sleeping on their nests even when the nests were empty of eggs.

Caption: trogons (a Harpactes species, perhaps Whitehead’s trogon H. whiteheadi) photographed asleep at night, on Borneo. Image: Matthew Connors, used with permission.

According to Burton (1969), birds don’t put their heads under their wings when they sleep, but instead bury the bill into the scapular feathers. He also stated that penguins are the only birds that properly hide the bill under the wing: they can’t submerge any part of their head within their scapular feathers, because their feathers are so short. I wonder what the hesperornithines did (they lacked long feathers and possessed strongly reduced wings).

Caption: at left, King penguin Aptenodytes patagonicus sleeping, bill tucked under wing. I can’t confirm that this is what it does show. However… at right, an illustration of exactly the same thing, from Burton (1969). Bonus mystery penguin in the background. Image: jpmatth, CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0 (original here), Burton (1969).

Unihemispheric sleep. So far I haven’t mentioned the fact that some animals sleep with only ‘half’ of the brain. This is called unihemispheric sleep (less frequently: unihemispherical sleep, properly unihemispheric slow-wave sleep or USWS), and it allows the animal to stay partly alert while in a restful state. Animals capable of this may be able to keep one eye open and alert for danger – this is termed unilateral eye closure or UEC – and may be able to regulate movement while resting. It’s well known for birds, including those that sleep on the wing, those that sleep on the water surface, and those that sleep in exposed terrestrial places like beaches and mudflats.

Caption: sleeping Mute swan Cygnus olor, not obviously employing unihemispheric sleep. Image: Neil Phillips, used with permission.

Unihemispheric sleep is important to marine mammals, since they doze at or near the water surface and still need to regulate their breathing (Lyamin et al. 2008). While cetaceans typically sleep unihemispherically in a horizontal pose (this is sometimes termed ‘logging’, since a sleeping whale can look superficially like a log), some pinnipeds – including Grey seal Halichoerus grypus, Northern fur seal Callorhinus ursinus and Walrus Odobenus rosmarus – hang in a vertical posture, as do some whales, sometimes. Weddell seals Leptonychotes weddelli are also reported to do this while submerged close to breathing holes in the ice. It has also been noted that some pinnipeds sleep underwater in cetacean fashion, “rising periodically, while still asleep apparently, to take a breath and then sinking again to continue their slumber” (Burton 1969, p. 27).

Caption: a captive Harbour seal Phoca vitulina sleeping underwater. Image: Rock Paper Lizard (thanks to Vasha for the heads-up).

Sleep behaviour in non-bird reptiles is not tremendously well studied and there aren’t many relevant studies out there. However, sea turtles have long been suspected to be unihemispheric sleepers. After all, they frequently sleep on the sea floor or even while resting on coral or submerged rocks. Crocodylians – caimans and crocodiles, at least – practise UEC and their behaviour during the phases when UEC is at play is similar (as goes how they respond to potential threats and so on) to that of birds and mammals that sleep unihemispherically (Kelly et al. 2015). They might, therefore, be engaging in unihemispheric sleep, though this has yet to be confirmed so far as I know.

Caption: a sleeping iguanian - an Ornate earless agama Aphaniotis ornata, a draconine agamid endemic to Borneo - photographed at night in a forest. Image: Matthew Connors, used with permission.

UEC is fairly well known in lizards, yet little studied. A study of Western fence lizard Sceloporus occidentalis again found that sleep behaviour during UEC – how the lizards kept open whichever eye was closest to the last observed position of a potential threat – was similar to that of birds (Mathews et al. 2006), suggesting a similar evolutionary function and that unihemispheric sleep might be at play. If crocodylians and lizards do exhibit both UEC and unihemispheric sleep, these might be ancestral for diapsids, or certainly archosaurs at least. Ergo, I’m going to promote the idea of unihemispheric sleep in non-bird dinosaurs.

Caption: not sure if this lizard - this is a Lacerta species, most likely a Western green lizard L. bilineata - is fully asleep, but at least it has one of its eyes closed. Image: Neil Phillips, used with permission.

Incidentally, REM sleep has also been reported for chameleons and in both desert iguanas (Dipsosaurus) and spiny-tailed iguanas (Ctenosaura). However, the reports are somewhat anecdotal and what’s been reported as REM sleep might instead describe observations where the animals were moving their eyes due to disturbance (Lesku et al. 2006).

That’ll do for now. This has been nothing like a thorough review of the subject and, as I said at the start, it’s been very superficial and I haven’t looked at the big questions about sleep behaviour.

Refs - -

Burton, M. 1969. Sleep and Hibernation in the Animal World. Odhams Books, London.

Couzens, D. 2008. Extreme Birds. HarperCollins, London.

Grzimek, B. 1956. Schlaf von Giraffen und Okapi. Naturwissenschaften 17, 406.

Kavanau, J. L. 1998. Vertebrates that never sleep: implications for sleep's basic function. Brain Research Bulletin 46, 269-279.

Kelly, M. L., Peters, R. A., Tisdale, R. K. & Lesku, J. A. 2015. Unihemispheric sleep in crocodilians? Journal of Experimental Biology 218, 3175-3178.

Lee-Chiong, T. L. 2006. Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Lesku, J. A., Rattenborg, N. C. & Amlaner, C. J. 2006. The evolution of sleep: a phylogenetic approach. In Lee-Chiong, T. L. (ed) Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, pp. 49-61.

Lesku, J. A., Rattenborg, N., Valcu, M., Vyssotski, A. L., Kuhn, S., Kuemmeth, F., Heirich, W. & Kempanaers, B. 2012. Adaptive sleep loss in polygynous pectoral sandpipers. Science 337, 1654-1658.

Lyamin, O. I., Manger, P. R., Ridgway, S. H., Mukhametov, L. M. & Siegel, J. M. 2008. Cetacean sleep: an unusual form of mammalian sleep. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 32, 1451-1484.

Lyamin, O., Pryaslova, J., Lance, V. & Siegel, J. 2005. Animal behaviour: continuous activity in cetaceans after birth. Nature 435, 1177.

Mathews, C. G., Lesku, J. A., Lima, S. L. & Amlaner, C. J. 2006. Asynchronous eye closure as an anti-predator behavior in the western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). Ethology 112, 286-292.

Novikov, G. A. 1972. The use of under-snow refuges among small birds of the sparrow family. Aquilo, Series Zoologica 13, 95-97.

Sulkava, S. 1969. On small birds spending the night in the snow. Aquilo, Series Zoologica 7, 33-37.

Perrins, C. 1992. Bird Life: An Introduction to the World of Birds. Magna Books, Liecester [sic].

Rattenborg, N. C. 2006. Do birds sleep in flight? Naturwissenschaften 93, 413-425.

Rattenborg, N. C., Voirin, B., Cruz, S. M., Tisdale, R., Dell’Omo, D., Lipp, H.-P. Wikelski, M. & Vyssotski, A. L. 2016. Evidence that birds sleep in mid-flight. Nature Communications 7: 12468.

Rechtschaffen, A., Gilliland, M. A., Bergmann, B. M. & Winter, J. B. 1983. Physiological correlates of prolonged sleep deprivation in rats. Science 221, 182-184.

Tobler, I. 1992. Behavioral sleep in the Asian elephant in captivity. Sleep 15, 1-12.

Tobler, I. & Schwierin, B. 1996. Behavioural sleep in the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) in a zoological garden. Journal of Sleep Research 5, 21-32.