Inspired by my recent article on South American wild dogs, I went to the trouble of digging out a very brief TetZoo ver 2 article I published in 2007 on the remarkable and beautiful 'fox on stilts', the Maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus (said article is here). My aim was to augment and update that text such that it might be a useful one-stop review on this animal.

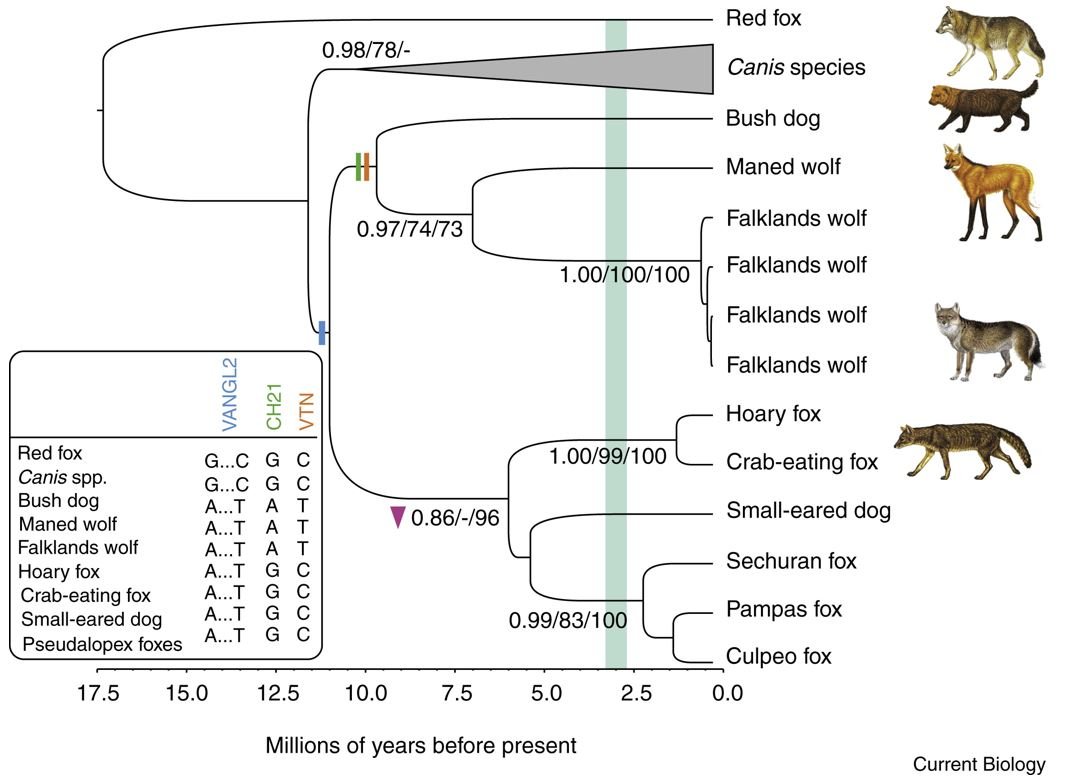

Caption: at left, Maned wolf in nice tidy lateral view. At right, the South American segment of Lindblad-Toh et al.’s (2005) canid cladogram. Images: Jonathan Wilkins, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Lindblad-Toh et al. (2005).

The problem is that our knowledge of the Maned wolf still isn’t all that extensive, and many of the things I’d like to talk about – concerning its scientific discovery, ecology, anatomy, role in indigenous folklore and so on – are not especially well served by the literature. Partly that’s because we know little, but partly it’s because these things haven’t (so far as I can tell) been collated and published, at least in English. With this caveat in mind, here are thoughts on this most incredible animal.

Caption: most clear images of Maned wolves are of captive individuals. This image is useful because it really emphasises the remarkably long, slender nature of the limbs: look at that forelimb in particular! Image: AndrewIves, public domain (original here).

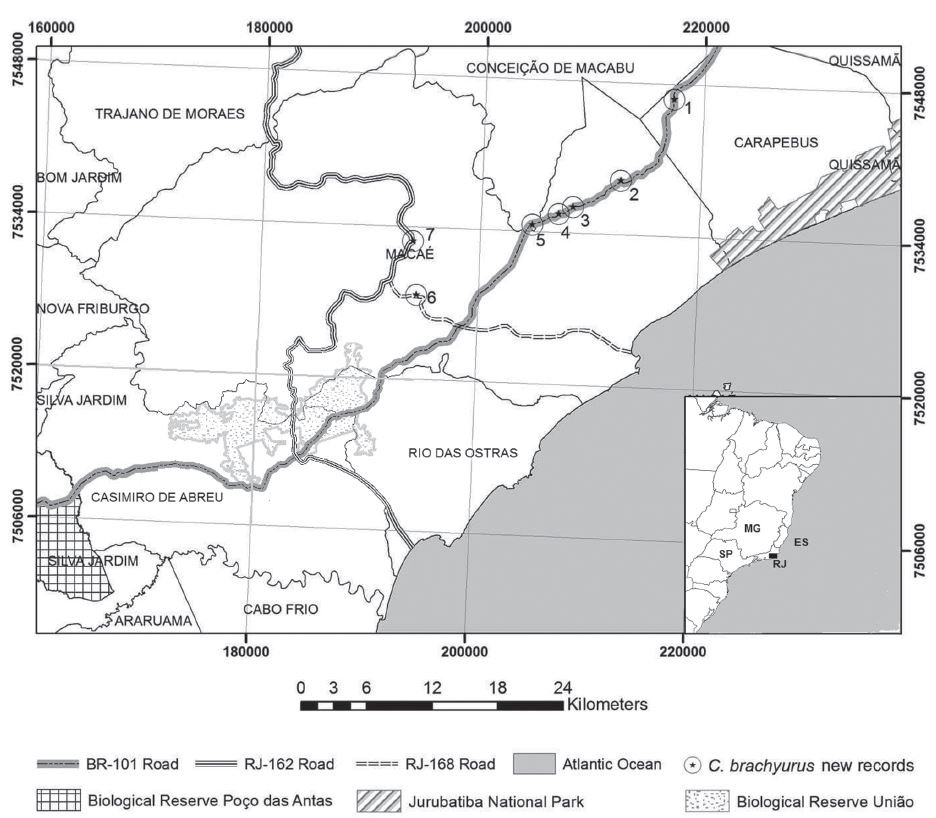

The Maned wolf is an inhabitant of South American grasslands and scrub forests, its range extending from north-eastern Brazil to northern Bolivia and south-eastern Peru, eastern Paraguay and parts of north-eastern Argentina and northern Uruguay (Macdonald & Sillero-Zubiri 2004). Several populations in Bolivia, Argentina, southern Brazil and Uruguay appear entirely isolated and it is suspected that some are nearly extinct, and perhaps extinct already. An exciting recent discovery concerns the presence of the species in coastal lowland habitats in Rio de Janeiro state in south-eastern Brazil (Xavier et al. 2017), albeit still around 12 km from the sea. It is presently uncertain whether the animals are moving into the littoral region due to habitat modification (namely, destruction of Atlantic forest) made by people, or whether they naturally always occurred in these places and it remained unknown until now. I hope the latter is true.

Caption: Maned wolf records from the coastal strip of Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil; as published by Xavier et al. (2017). I’ve been to Rio de Janeiro, but sadly nowhere where you might be able to see Maned wolves.

Maned wolves are solitary, wide-ranging, and occur at low density, pairs in the Serra da Canastra National Park in Brazil having home ranges of around 20-30 km sq but with ranges of up to 105 km sq known from elsewhere Uruguay (Dietz 1985, Macdonald & Sillero-Zubiri 2004).

The wild population is estimated at 17,000 according to the IUCN’s Canid Specialist Group (though note that this figure is probably over 10 years old); this is declining, the main cause being the conversion of grassland to agricultural pasture (including soybean plantation). It has been suggested that Maned wolves might benefit from deforestation and the resultant spread of poor-quality grasslands, but I don’t know if this is anything other than a speculation. As is typical for mid-sized mammals of tropical savannahs, Maned wolves do not fare well on roads and they often suffer as traffic victims. One study found that around 50% of all pups born in a given year died on roads (Rodden et al. 2004).

Caption: nobody likes seeing a beautiful animal dead at the side of the road, but there’s no escaping the fact that death on the roads is a hugely significant global issue for a long list of species. This deceased Brazilian Maned wolf was photographed on BR 101/North (NPM 1305); the photo comes from Xavier et al. (2017).

Scientific discovery and phylogeny. The Maned wolf’s scientific history began in 1801 when the Spanish naturalist, engineer and army general Félix de Azara brought it to attention, referring to it by the Paraguayan name Agouara Gouazou (to use his spelling) (Dietz 1984). Several authors – including Johann Rudolph Rengger and Charles Hamilton Smith, both writing during the 1830s – later described how ‘aguara’ originated as an onomatopoeic reference to the call of this animal, but it’s also been stated that ‘aguara’ is the word for ‘fox’ in the Guarani language of Paraguay.

Caption: ok, this photo has to be taken in ‘the wild’, right? I don’t know anything about the context of this image but I’m curious. UPDATE: very obviously photographed at the famous Santuário do Caraça monastery in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Thanks to Robin Beck and others for the info. Image: Lucia Coelho, public domain (original here).

Following Azara’s report, the animal was formally named as a new species – Canis brachyurus – by German zoologist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger in 1815. Additional studies, this time reporting specimens from Paraguay and Brazil, were published by other European writers during the 1810s and 20s. These new specimens were thought to represent new species, named at the time as species of Vulpes or Canis (Dietz 1985). In his 1839 work The Natural History of Dogs, Charles Hamilton Smith (1839) decided that the Maned wolf was deserving of its own genus, and here’s where the name Chrysocyon – ‘golden dog’ – originated. Hamilton Smith (1839) included the Maned wolf within a group of South American dogs that, following Azara, he termed the aguaras, and so labelled the species as the Maned aguara. I admit to preferring this name to ‘Maned wolf’.

Caption: this depiction of the Maned wolf from Charles Hamilton Smith’s 1839 The Natural History of Dogs makes the animal look more robust and wolf-like than it really is; I think it’s obvious that the artist (whom I think might have been Hamilton Smith himself) was working from a description rather than a specimen. There are some technical errors: the white end of the tail is missing and the legs and feet aren’t dark enough.

On that note, Chrysocyon isn’t a ‘wolf’ at all, nor especially close to Canis. Actually, the idea of a sister-group relationship between Chrysocyon and Canis was suggested in the past on the basis of anatomical similarity (Berta 1987) but is no longer thought correct. Molecular data shows instead that Chrysocyon is part of the South American clade Cerdocyonina, its closest living relative being the very different Bush dog Speothos venaticus (Wayne et al. 1997, Lindblad Toh et al. 2005, Slater et al. 2009).

While it’s tempting to suggest that these two diverged after moving into South America from the north, molecular clock data is a bit ambiguous on this, there being some indications that the split (and other divergences within the South American canid clade) might have occurred before the formation of the Central American land-bridge. In addition, palaeontologists specialising on dogs have long said that fossils identifiable as Chrysocyon are present in the North American record (specifically, that of Arizona and New Mexico) of around 5-6 million years ago (Wang & Tedford 2008), this meaning – again – that Chrysocyon existed before its lineage had moved into South America. However, the fossils concerned are fragmentary and the possibility exists that they could be from misidentified archaic members of the Chrysocyon + Speothos clade, not from Chrysocyon itself (Perini et al. 2010). It should be noted that the Warrah or Falklands wolf Dusicyon australis is likely also a member of the Chrysocyon + Speothos clade (Slater et al. 2009), as are the fossil Protocyon and Theriodictis species (Perini et al. 2010).

Caption: Slater et al.’s (2009) canid phylogeny, focusing on the affinities of the Falklands wolf rather than the Maned wolf. Its relevance for us here is that the divergence dates of the Maned wolf (and Bush dog too) put their origins well prior to the origin of the Central American land-bridge. This view has been challenged by more recent studies: there are competing views on divergence dates in this clade. Image: Slater et al. (2009).

Incidentally, a few anatomical traits do appear shared by Chrysocyon and Speothos. Both have a rhinarium that extends to the upper lip and both have third and fourth digits where the digital pads are fused at their proximal ends (Dietz 1985).

Anatomy, ecology, behaviour. Maned wolves are the largest living South American canids, reaching 25 kg (some sources say 33 kg), 1.2 m in head and body length (the tail adds a further 45 cm) and 90 cm in height. The narrow body and incredibly long, slender legs are unique and thought to be specialisations for grassland life. The very long legs (each of which is longer than the entire spine… I assume excluding the tail; Dietz 1985) are also linked to the pacing gait the animal has, this being typical for quadrupeds where limb length exceeds body length.

Caption: captive Maned wolf, photographed at Beardsley Zoo, Connecticut (USA). Image: Sage Ross, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

The pelt is soft, long and orange-brown but for a white throat and tail end, and black legs and shoulder region. Sexual dimorphism isn’t obvious though males are a bit larger than females. A (so far unique) melanistic individual was photographed in the Brazilian Cerrado in 2013 (Ferreira et al. 2017) and has to be one of the most remarkable wild dogs ever seen.

Caption: one of Ferreira et al.’s (2017) camera-trap images of a melanistic Maned wolf. This particular photo has been entered in photography competitions and won the People’s Choice Award in the World Land Trust competition: for more information on that go here.

Caption: yuuuup, ‘werewolves’ are real, and here’s the proof. Ferreira et al. (2017) didn’t just take the famous photo you see above. They took this one too. Wow!

Maned wolves are well known for being predators of large rodents (like mara) and similar-sized vertebrate prey (including armadillos and snakes). Fishes and arthropods are also eaten when available. There are rare reports of them killing brocket, Pampas deer Ozotoceros bezoarticus and tamandua, and they will also scavenge on roadkill (Hunter & Barrett 2011). Like so many wild dogs, they are believed to predate on domestic animals, though what real impact they have is not well understood. The Maned wolf is notably omnivorous and over 100 fruiting plant species are recorded as part of their diet. They are particularly fond of the 'fruta da lobo' (Wolf apple or Lobeira Solanum lycocarpum), hence its name. Bell peppers, coffee, papaya and grass are also eaten (Hunter & Barrett 2011).

Caption: fruit of Solanum lycocarpum, the Wolf apple or Lobeira, photographed in Brazil. Image: João Medeiros, CC BY 2.0 (original here).

Based on its anatomy and round pupils, I think it might be sensible to assume that the Maned wolf is diurnal. But it seems instead to be cathemeral (active mostly at dawn and dusk) and to mostly remain hidden during the day. It’s mostly solitary but pairs do move and stay together during the breeding season, at which time they defend their territory from other pairs. They’re not long-lived, with 15 being the greatest age reported for a captive individual. Puma and domestic dog are both confirmed as mortal enemies of the species (Hunter & Barrett 2011).

Caption: I was initially hoping that this photo depicts a Maned wolf in the wild… but no, it was taken at Salzburg Zoo. Image: Robin Müller, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

People and the Maned wolf. Finally, the feelings that people have toward Maned wolves vary substantially, ranging from tolerance to superstitious fear. It would be fascinating to know what role the Maned wolf has in local mythology and tradition: I think we can be confident that such a remarkable, rare, ecologically aberrant animal has surely been imagined or depicted in interesting ways throughout history, it’s just that this has (apparently) mostly gone unreported.

It should be mentioned here that a 2014 volume – Adriana Consorte-McCrea and Eliana Ferraz Santos’s Ecology and Conservation of the Maned Wolf: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (Consorte-McCrea & Santos 2014) – may include a great deal of useful information on these issues, but at the time of writing I cannot say because I haven’t been able to consult it.

Finally, there is now a large literature on husbandry, health and best practise concerning this species in captivity. They’ve proven trainable in captivity via positive reinforcement but very often suffer from bladder and kidney issues believed linked to deficiencies in their diet. As of 2012, nearly 400 captive individuals were housed in around 150 collections worldwide. I have a distinct recollection myself of seeing captive individuals on more than one occasion at my local zoo (Marwell Wildlife in southern England), the first place to breed them in the UK, but don’t think I’ve seen any recently. And right now I feel the need to: I’m definitely up for a good zoo trip.

And that’s where we'll end this brief look at this most amazing animal.

For previous TetZoo articles on dogs and other carnivorans, see…

The once mighty red panda empire, April 2008

The most inconvenient seal, June 2010

Hunter and Barrett's A Field Guide to the Carnivores of the World, March 2013

Another meeting with the Hayling Island Jungle cat, March 2013

Conservation Concerns for South America's Remarkable Endemic Dogs, Revisited for 2022, January 2022

This blog benefits from your support. Thank you to those who help via patreon!

Refs - -

Berta, A. 1987. Origin, diversification, and zoogeography of the South American Canidae. Fieldiana: Zoology 39, 455-471.

Consorte-McCrea, A. G. & Santos, E. F. 2014. Ecology and Conservation of the Maned Wolf: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Dietz, J. M. 1984. Ecology and social organization of the Maned wolf Chrysocyon brachyurus. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 392, 1-51.

Dietz, J. M. 1985. Chrysocyon brachyurus. Mammalian Species 234, 1-4.

Hamilton Smith, C. 1839. The Natural History of Dogs. W. H. Lizards, Edinburgh.

Hunter, L. & Barrett, P. 2011. Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Macdonald, D. W. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. 2004. Wild canids – an introduction and dramatis personae. In Macdonald, D. W. & Sillero-Zubiri, C. (eds) Biology and Conservation of Wild Canids. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 3-36.

Perini, F. A., Russo, C. A. M. & Schrago, C. G. 2010. The evolution of South American endemic canids: a history of rapid diversification and morphological parallelism. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23, 311-322.

Rodden, M. D., Rodrigues, F. & Bestelmeyer, S. 2004. Maned Wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus). In Sillero-Zubiri, C., Hoffmann, M. & Macdonald, D. W. (eds) Canids, Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, U.K., pp. 38-44.

Wang, X. & Tedford, R. H. 2008. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia University Press, New York.

Wayne, R. K., Geffen, E., Girman, D. J., Koepfli, K. P., Lau, L. M. & Marshall, C. R. 1997. Molecular systematics of the Canidae. Systematic Biology 46, 622-653.