Of the several phantasmal creatures associated with the British and European countryside, among the most widespread and ancient is the Black Dog...

Caption: it is no ordinary dog that is merely black, but…. The Black Dog.

Here I have to specify that ‘Black Dog’ as used throughout this article does not refer simply to domestic dogs that are black, but to a specific sort of frightening, monstrous creature that has the form of a very large, black, shaggy-coated dog, is mostly associated with rural roads, town edges and green places, and which is described as atypical relative to domestic dogs and, furthermore, able to generate an unusual amount of fear in those who encounter it. In discussing the Black Dog, we almost certainly aren’t talking about an actual animal or race of animals but instead some kind of folkloric or cultural entity, perhaps meaning that this article is out of place on a blog devoted to zoology. But read on.

The Black Dog is a creature of contradiction, stories variously describing it as a malevolent or menacing presence, as an associate of witchcraft, Satanic goings-on, or the afterlife, as Satan himself, as a terrifying, hellish beast that can burn and even kill, as an omen or portent associated with misfortune or impending death, as a benign, known and regular feature of the landscape, or even as a guardian or protector.

Caption: at least some renditions of Black Dogs (I think made without reference to the actual accounts) show them as hound-like and short-coated. At left, the spectral hound of the Baskervilles as illustrated by Sidney Paget for the 1901-1902 serialisation of Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles. At right, a Black Dog as visualised by Gino D’Achille for the cover of Janet and Colin Bord’s 1981 Alien Animals.

Names and their alleged origins. A large number of local names are attached to the Black Dog, those from Britain including Barguest, Black Shuck, Capelthwaite, Galley Trot, Gurt Dog, Hairy Jack, Hooter, Old Scarpe, Old Shock, Padfoot, Scarfe, Shucky Dog, Shug Monster, Skeff, Skriker, Striker and Trash. Numerous efforts to find the etymologies of these names exist; in his Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland, Graham McEwan (1986) reviewed suggestions that certain of them might have their roots in old words associated with gnawing or biting, with Satan, with words for spirit, ghost, elf, or shining, with howling, with the noisy ‘striking’ or ‘sloshing’ sounds of the Black Dog’s feet, with the shagginess of its coat, with the bear-like appearance of the Black Dog, with the Black Dog’s association with towns, barrows, hills or funeral processions, or with its role as a guardian of treasure (McEwan 1986).

Caption: 17th century images of the Black Dog of Newgate Prison, London. This monstrous creature was said to have a massive chain around its neck and to be associated with executions or with the avenging of the death of a sorcerer… it’s all complicated and confusing. A book called The Discovery of a London Monster Called the Black Dog of Newgate was published about the case in 1638.

This diversity of associations makes me wonder if people were ever really describing the same one thing. I mean: if names used for specific, regional variants of the Black Dog really are meant to be synonymous with ‘town ghost’, ‘hill ghost’, ‘barrow ghost’ or ‘treasure guardian’, I’m inclined to think that ‘Black Dog’ is better imagined as a synonym of ‘amorphous dark non-humanoid phantom’. Having said that, a good number of the tales and accounts really do describe big, black, shaggy-coated dog-like animals, and it’s those accounts I’m interested in.

Black Dogs are generally large: mostly bigger than a familiar dog like a German shepherd or Labrador, and quite often said to be exceptionally big, some accounts describing them as being as tall as a table or the size of a calf. The eyes are often said to be strikingly large, and to glow, usually red. This is thought to reflect an internally generated, spectral glow and not be a reflection of lights held by the witness. A few accounts pertaining to Devon describe the Black Dog as headless and Black Shuck is said in some stories to only have one, centrally positioned eye.

Caption: a Black Dog – of the sort recounted in the relevant tales – to scale with a person and a mid-size pet dog. Image: Darren Naish.

Occasionally, there’s mention of clanking or swinging chains around the Black Dog’s neck, or of especially noisy paws that make a clattering, splashing or striking sound on the surface of the road. Baying or shrieking sounds are associated with some Black Dogs. A few accounts describe the animal opening its mouth to reveal a glowing interior, and sometimes glowing fumes or a mist emanates from the mouth too. One or two accounts make mention of a sulferous odour.

Caption: at left, McEwan’s Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland, a very useful source of Black Dog information. At right: several smaller books discuss or recount various of the local Black Dog legends, and here’s one of them.

The places and the times. Black Dog stories and accounts come from essentially the whole of the British Isles, though there’s the impression that Suffolk, East Anglia and Lincolnshire in the east, Devon in the west, and Yorkshire in the north-east are where the majority of accounts originate. The eponymous hound of Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1901-1902 The Hound of the Baskervilles, set on Dartmoor in Devon, was apparently based on the Yeth Hound, a legendary Black Dog local to the area.

Caption: The Black Dog Inn in the village of Black Dog, Devon. Image from The Black Dog Inn website.

Various places across Britain are named after the Black Dog, including certain roads, lanes, pubs, and the village Black Dog in Devon. I recently visited one such pub in my native Hampshire, though I remain unsure whether it was named for a proper Black Dog or just a Labrador of dark hue.

Caption: I made a special trip to The Black Dog, Waltham Chase, a few weeks ago. It was closed. The signage makes it seem that the pub is named after black dogs of normal, domesticated form, but I’d love to have this confirmed….. or otherwise. Images: Darren Naish.

Black Dog tales are not restricted to the UK. They also come from the Republic of Ireland, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, Poland, the USA and Canada (Bord & Bord 1981, McEwan 1986), and there are stories from Mexico, Central and South American countries too that describe similar creatures. Whether this reflects a shared folkloric heritage, cultural transmission, the coincidental development of similar tales, or the widespread nature of a genuine phenomenon remains to be established.

Black Dog accounts typically involve lonely countryside roads, and the witness is virtually always alone when the encounter happens. A Black Dog story most often involves the person hearing the dog approaching and then seeing it, and then realising by virtue of its size, frightening appearance and unusual features that it is not a normal dog. Its approach sometimes causes the person to flee or hide, but more normally the Black Dog walks alongside the person for a while before disappearing or moving into a gap in a hedge or bend in the road. There are a few accounts where the Black Dog was seen running alongside by the occupants of a vehicle, and there are a few stories of them being seen indoors, and of disappearing after leaving a room.

While it might sound from everything I’ve described so far that Black Dog stories are long-ago tales from the Middle Ages or thereabouts, a great many are surprisingly modern. Reading through the numerous tales repeated in McEwan (1986) and other sources, it’s striking how many are from the 20th century, including from the 1940s, 50s and as recently as the 70s.

Caption: the weathervane at St Mary’s Church, Bungay, features the town’s famous Black Dog; note the associated lightning. Image: Better in Bungay.

A Strange and Terrible Wonder. Among the most famous of Black Dog stories is that reported by Abraham Fleming in his 1577 booklet A Strange and Terrible Wonder. Fleming was relating an account that happened in the churches of Bungay and Blythburgh, Suffolk, on the morning of Sunday 4th August. After a thunderstorm, a great black dog – accompanied by flashes of fire – appeared within the Bungay church and ran among the congregation. It passed between two people, both kneeling in prayer, and killed them both by attacks to the neck. It grabbed the neck of another person – a man – and, though succeeding in causing the skin of his neck to become shrunk “as it were a peece of lether scorched in a hot fire”, did not kill him.

Caption: cover of Abraham Fleming’s 1577 pamphlet on the Bungay-Blythburgh event. While compiling this article, I’ve discovered that people have naughtily modified the image included in Fleming’s pamphlet. The version shown in mystery animal books (e.g., Bord & Bord 1981, McEwan 1986) is the one at right. But the version apparently included in Fleming’s original publication (which I haven’t seen myself) gives the animal some sort of curved horn on the forehead, as we can see at left.

The Black Dog then somehow moved to the church at Blythburgh about 7 miles (10 km) away where similar events ensued. There, it killed three people and burnt the hand of a fourth. This is the only Black Dog account associated with any claimed physical evidence of its manifestation, since it supposedly leapt through a door at the end of the church and left black scorch marks on the wood. Whether the scorch marks existed first, and then inspired the placement of the Black Dog event, or whether something caused the scorch marks and then ‘became’ – through retelling, embellishment, misunderstanding or misinterpretation – a Black Dog remains unknown.

Caption: the Blythburgh Church (Suffolk) door, marked with burns connected to the Black Dog story of 1577. At right is the 1970s/early 1980s photo of the same door that features in several mystery animal books (it was taken at Harvest Festival time, hence the tools and hay). Images: Atlas Obscura; Bord & Bord (1981).

Black Dogs as real animals. I don’t think anyone has seriously proposed that Black Dog encounters describe observations of some sort of real-world giant black canid, like an unrecognised form of solitary, large-bodied, melanistic, late-surviving wolf, or a hitherto unknown species of anatomically and behaviourally novel European canid. I should note that a few large dogs reported from the British countryside at various points during the 20th century were feral or wild-living large domestic dogs, but they lacked the features linked to legendary Black Dogs (Shuker 1991).

Caption: every now and then, people see and report big (sometimes dangerous, wild-living) dogs from the UK countryside, but dogs that aren’t really of the iconic Black Dog type. This shaggy creature was photographed by falconer Martin Whitley at Hound Tor, Dartmoor, in 2007, and implied for a while to be a monster. Limb proportions and other features show that it’s a domestic dog with Bearded collie in its ancestry. Images: (c) Martin Whitley.

The suggestion that some local English names used for Black Dogs (specifically, Barguest and its variants) had their origins in its bear-like form (McEwan 1986) raise the possibility that some Black Dog accounts were based on sightings of actual bears. The Brown bear Ursus arctos became extinct in Britain around 1000-1500 years ago, perhaps during the early Medieval period (O’Regan 2018), and this is too long ago to be linked to Black Dog stories. Anyway, given the familiarity that people have with bears – even in Britain – any idea that bears might have been dubbed ‘dogs’ of any sort is unlikely. I do wonder, though, if the idea of spectral or phantom bears has been confused with, or absorbed into, Black Dog lore.

Caption: could Brown bears – denizens of the UK until about 1000 years ago (and of course widespread in those other places where Black Dog legends occur) - be inspirational for some Black Dog stories? I don’t think so. This bear was photographed in Finland. Image: Frank Vassen, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

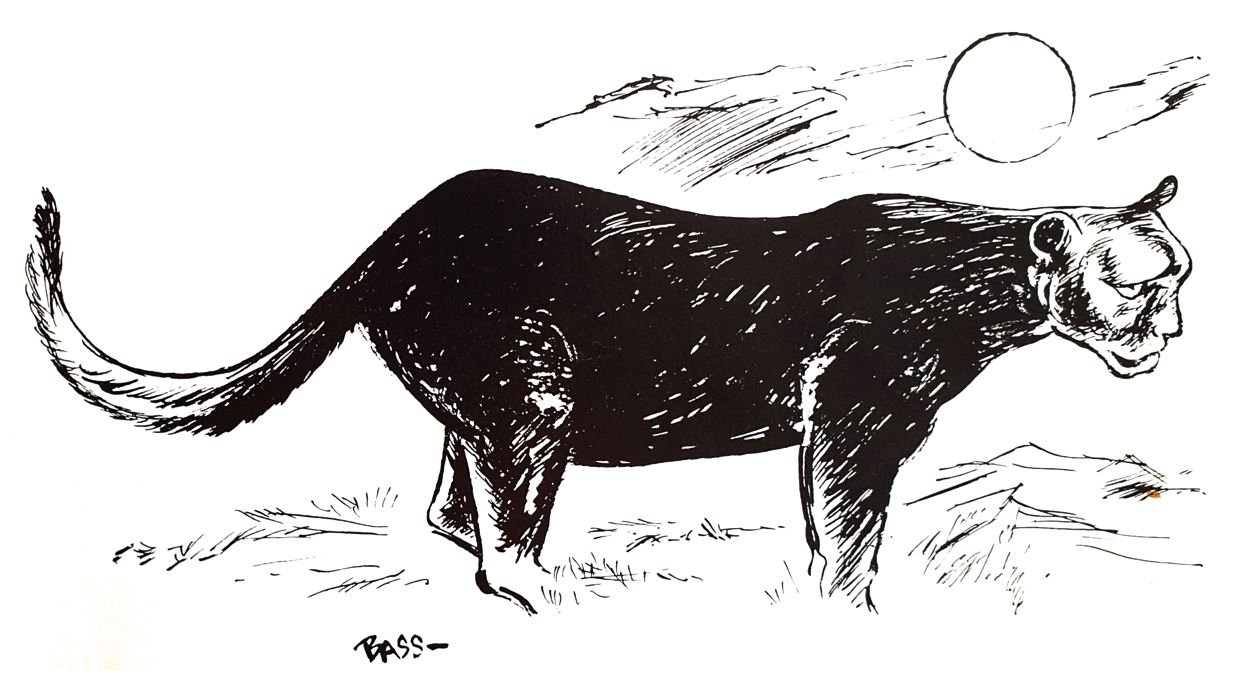

One researcher – author Di Francis, who died in 2021 – argued that Black Dogs may indeed be descriptions of a real carnivoran species, but one that’s of felid identity, not canid. Francis was an advocate (if not the sole advocate) of the hypothesis that claimed British big cat encounters were not only zoologically valid, but that they described a new kind of cat unknown to science, and belonging to an ancient lineage distinct from familiar groups within the cat family tree. Her hypothesis was advocated in a few popular books – most notably 1981’s Cat Country (Francis 1981) – but was and is essentially unknown and ignored outside the niche community interested in the British big cat phenomenon. I think it’s fair to say that the proposal was extremely unpopular and that it failed to win adherents.

Were her hypothesis true or likely, it would benefit from some indication that people throughout the ages had encountered her novel British cat species and had reason to describe it to others. Francis suggested that Black Dog accounts were not folkloric but actual descriptions of big black cats; she argued that Black Dog accounts merely described the creature within a ‘dog’ frame of reference because the people observing these animals were unfamiliar with large cats. She argued that the ‘striking’ sounds associated with Black Dog feet were consistent with her view that the British big cat has non-retractile claws, that Black Dog accounts mentioning headlessness are consistent with the low neck carriage of cats relative to the more erect one of dogs, and she also noted that the sounds made by Black Dogs, and the leaping behaviour mentioned in a few accounts, were also more consistent with a cat identity than a dog one (Francis 1981).

Caption: the British big cat as imagined by Francis (1981), and as reconstructed by Reginald Bass. The animal is supposed to have a puma-like head on a leopard-like body but I always think that this image makes the head look too humanoid. Image: Francis (1981).

As is so often the case with cryptozoological hypotheses that aim to turn an inconsistently described, cultural entity into a flesh and blood animal, I think that Francis’s proposal is a whole lot of fun, and I’m entertained by the fact that the Black Dog illustrated in Fleming’s 1577 booklet could be interpreted as a cat-like animal rather than a dog-like one. But… do I take it seriously? No. I think her effort to turn Black Dogs into cats reflects a cherry-picking of traits that are either not convincing (would a cat with non-retractile claws really be noisy on a road? Would a big cat interpreted as a dog really be interpreted as headless?), or ignore the obvious dog-like demeanour of this creature.

The Black Dog as an psychological phenomenon. Could there be a real-world explanation for Black Dogs? There’s a tendency in the mystery animal literature for Black Dog accounts – as there is for mystery animal accounts in general – to be interpreted as eyewitness observations of real animals. I’m not necessarily discounting this proposed explanation across the board, but the long-ago nature of many Black Dog accounts sure makes them sound folkloric and allegorical: as tales that are meant to entertain or frighten, and perhaps function as warnings about travelling certain routes at unsafe hours. The associations I’ve mentioned with churches and the Christian devil imply that belief in the Black Dog has been encouraged since it promotes some sort of adherence to religious belief.

Caption: my attempt to convey what a Black Dog encounter might be like according to various of the stories on record… Image: Darren Naish.

But if we entertain the idea that at least some of the stories (remember, they’re reported as recently as a few decades ago) describe real experiences of some sort, could there be a non-zoological explanation?

As I noted earlier, the massive diversity of Black Dogs sure makes it sound as if people have described all manner of different things. What’s been suggested is that people might have seen – or, at least, perceived – an amorphous dark shape, only vaguely of dog-like size and form, and interpreted or described it as a Black Dog because that was the only thing they could liken it to. One possible explanation for Black Dog sightings is that they represent hallucinations. Maybe, in certain situations, people perceive a dark shape (due to tiredness, intoxication, eye defects or a brain disorder) and it’s this that’s ‘the Black Dog’. This would be an ‘internal’, ‘psychological’ or ‘human’ explanation for the phenomenon.

Caption: the Spring 1998 issue of Strange Magazine featured several articles on phantom Black Dogs, focusing in particular on accounts from Maryland, USA. The features ascribed to these Black Dogs are the same as those of the mostly British Black Dogs discussed in this article.

The Black Dog as an environmental phenomenon. But an ‘external’ or ‘environmental’ explanation is on the table too. Ever since the 1990s it’s been widely proposed that hauntings – involving claimed sightings of ghosts or phantoms, feelings of dread or unease, inexplicable sounds and unexpected temperature fluctuations – might be connected to unusual electromagnetic and geomagnetic phenomena (e.g., Persinger & Koren 2001, Persinger et al. 2001, Roll & Persinger 2001, Braithwaite 2004). Infrasound in both the modern built environment and in older structures (specifically, a 14th century cellar) has been connected to hauntings too, including apparent observations (in peripheral vision) of human-shaped phantoms (Tandy & Lawrence 1998, Tandy 2000).

Caption: one of your senses (you have many more than five) detects something, and your brain turns that something into an amorphous shape at the edge of your vision… perhaps. Could this sort of thing explain observations of Black Dogs and other phantoms? Image: Darren Naish.

It must be emphasised that the linking of hauntings to these things is a hypothesis, and an under-tested one that hasn’t necessarily worked well as an explanation in experiments (French et al. 2009, Dagnall et al. 2020). It’s also worth noting that people’s tendency to apparently perceive exotic or supposedly paranormal phenomena is contingent on their beliefs and suggestibility, so ‘believing’ or merely knowing about a supposed phenomenon or entity has some influence on what the person thinks is happening.

Where I’m going with this is as follows: I wonder if key locations, imbued with certain properties relating to geomagnetism, infrasound or something else, OR particular electromagnetic weather events have resulted in people experiencing something, interpreting that something as observations of a vague dark object, and it is this “vague dark object” that is the Black Dog. This all sounds tenuous and arm-wavy, and it is, but it’s not a ridiculous hypothesis given the weirdness of human perception (Tandy & Lawrence 1998, Tandy 2000) and the power of suggestion and belief.

Caption: the great black shaggy spectral hound, with glowing eyes. Could people have experienced something, but something that wasn’t of biological origin? Image: Kurt Komodo, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

None of what I’m saying is entirely novel. The idea that sightings of monsters, phantoms and ghosts might be linked to unusual properties of the landscape (like, the presence of underground watercourses, specific rock types, seismic activity and so on) has been mused on here and there in the past, and a few features of Black Dog accounts that seem linked to storms, lightning or electrical discharge led McEwan (1986) to consider that ‘Black Dog’ accounts might be misinterpreted stories about ball lightning. You’ll recall the scorch marks from the Blythburgh church.

Whatever the root of this phenomenon, I find the Black Dog as a mythical, semi-real feature of the landscape a fascinating one, and I’m often surprised that such a ubiquitous, long-standing mythical creature isn’t better known. And I wonder if a better understanding of this alleged creature might help explain other ‘monsters’, whether real or imagined.

For previous TetZoo articles on related issues, see…

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness, August 2019

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos, August 2020

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, October 2020

The Lake Dakataua ‘Migo’ Lake Monster Footage of 1994, February 2021

What Was the Montauk Monster? A Look Back to 2008, October 2021

Santa Cruz’s Duck-Billed Elephant Monster, Definitively Identified, November 2021

Refs - -

Bord, J. & Bord, C. 1981. Alien Animals. Granada Publishing, London.

Braithwaite, J. J. 2004. Magnetic variances associated with ‘haunt-type’ experiences: a comparison using time-synchronised baseline measurements. European Journal of Parapsychology 19, 3-28.

Dagnall, N., Drinkwater, K. G., O’Keeffe, C., Ventola, A., LAythe, B., Jawer, M. A., Massullo, B., Caputo, G. B. & Houran, J. 2020. Things that go bump in the literature: an environment appraisal of ‘haunted houses’. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1328.

Francis, D. 1981. Cat Country: the Quest for the British Big Cat. David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

French, C. C., Haque, U., Bunton-Stasyshyn, R. & Davis, R. 2009. The "Haunt" project: an attempt to build a "haunted" room by manipulating complex electromagnetic fields and infrasound. Cortex 45, 619-629.

McEwan, G. J. 1986. Mystery Animals of Britain and Ireland. Robert Hale, London.

O’Regan, H. J. 2018. The presence of the brown bear Ursus arctos in Holocene Britain: a review of the evidence. Mammal Review 48, 229-244.

Persinger, M. A. & Koren, S. A. 2001. Predicting the characteristics of haunt phenomena from geomagnetic factors and brain sensitivity: evidence from field and experimental studies. In Houran, J. & Lange, R. (eds) Hauntings and Poltergeists: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC, pp. 179-194.

Persinger, M. A., Koren, S. A. & O’Connor R. P. 2001. Geophysical variables and behavior: CIV. Power frequency magnetic field transients (5 microTesla) and reports of haunt experiences within an electronically dense house. Perceptual and Motor Skills 92, 673-674.

Roll, W. G. & Persinger, M. A. 2001. Investigations of poltergeists and haunts: a review and interpretation. In Houran, J. & Lange, R. (eds) Hauntings and Poltergeists: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. McFarland & Company, Jefferson, NC, pp. 123-163.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1991. Extraordinary Animals Worldwide. Robert Hale, London.

Tandy, V. 2000. Something in the cellar. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 64, 129-140.

Tandy, V. & Lawrence, T. R. 1998. The ghost in the machine. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 62, 360-364.