Regular readers of Tetrapod Zoology will be aware that I’m a big fan of cassowaries….

Caption: cassowaries (of three different taxa) at the Cassowary Conservancy of North America (CCNA) in Fort Pierce, Florida. Images: Darren Naish.

Everything about cassowaries is remarkable, and yet we know surprisingly little about them. Indeed, many aspects of cassowary biology and evolutionary history can be considered poorly known and under-studied.

Sad to say, I’ve never seen a single cassowary in the wild but – somewhat bizarrely – my residency in the UK means that I have relatively easy access to the world’s single most important scientific collection of cassowaries, that amassed by Walter Rothschild during Victorian times, and now curated at the Natural History Museum at Tring. In addition, the UK has – throughout my lifetime – always had at least some cassowaries in its various zoos and other live animal collections, so I have seen live cassowaries – sometimes at close range – on numerous occasions.

Caption: I’ve seen cassowaries on a reasonable number of occasions before, always in zoos, and always in the UK. These photos all show birds – all Southern or Double-wattled cassowaries Casuarius casuarius – at Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland. Images: Darren Naish.

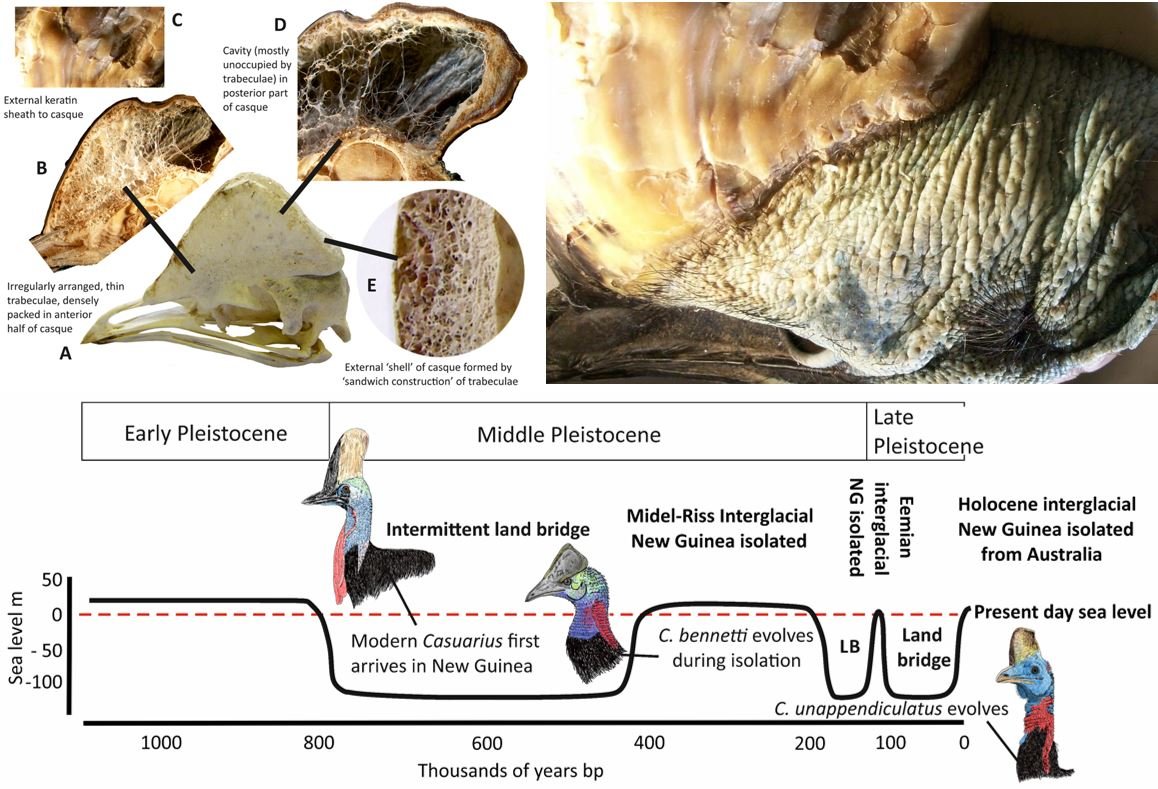

Looking at and knowing about animals is all fine and good, but contributing to the canon of published knowledge on them is better. I initiated an academic study of cassowary foot anatomy during my PhD years back in 1998. Alas, the results were too poor to warrant completion of the study. More recently, I co-authored a study on the group’s cranial anatomy and evolution with cassowary expert Richard Perron (Naish & Perron 2016). Richard was a font of knowledge on these birds and developed novel ideas on their evolutionary history that I was keen to get into print. Sadly, he died in 2017.

Caption: I’ve written here several times about the cassowary research I published with Richard Perron. We published anatomical observations of the casque interior, presented a DNA-based phylogeny, and devised a hypothesis of cassowary evolution. Follow the links at the end of this article for more on this research. Images: Richard Perron and Darren Naish/Naish & Perron (2016).

In recent years, renewed interest in cassowaries has resulted in the publication of several important and interesting new studies. Eastick et al. (2019) argued that cassowary casques have an important function as ‘thermal windows’ (basically, as heat dumping structures), McInerney et al. (2019) studied laryngeal anatomy in cassowaries, Elliason & Clarke (2020) discussed a new form of structure-based iridescence in cassowary feathers, and Green & Gignac (2020) looked at the growth changes that occur in casque anatomy as cassowaries mature. Other studies have been published too: for more info see Inside the Cassowary's Casque, Updated for 2022.

The ’Green’ mentioned in connection with those studies is Dr Todd Green, cassowary specialist and Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow based at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine. Todd and I have been corresponding and catching up at conferences over the past several years and it’s been great to hear about his various in-prep cassowary-themed projects. In fact, one of these studies was just published: it focuses on the issue of how cassowary casques can be used as modern analogues for the ornaments of extinct dinosaurs (Green & Gignac 2023). I’m excited by this renewed academic interest in cassowaries. It looks like we’re in the early stages of a new golden age in cassowary study.

Caption: Like a lot of birds, cassowaries are able to rotate their feet at several of the hindlimb joints (meaning that the joints don’t just work in hinge-like fashion as usually stated). You can see that here, since the left foot is rotated quite some degree toward the midline. Image: Darren Naish.

On that note, studying cassowaries in their homeland is difficult (see Andrew Mack’s 2013 book Searching for Pekpek for a good discussion of that; Mack 2013). For those of us in Europe and the Americas, the good news is that – as mentioned above – they’re often kept in collections here.

Cassowaries were bred in captivity some decades ago. But my impression is that – prior to about 1970 – any call for cassowaries to be added to captive collections required them to be taken from the wild. Within recent decades, however, expertise in cassowary husbandry and breeding has arisen in the Philippines, Australia and the USA.

A cassowary relocation project. Florida has emerged as an important place for the keeping and breeding of cassowaries, partly for the obvious reason that the tropical conditions are good for them. And here’s where we come to the reason for this article.

Caption: Dr Todd Green has devoted a considerable chunk of his adult life to research on cassowaries and other giant flightless birds. Todd knows these birds extraordinarily well, and is interested in their welfare, conservation and husbandry as much as in technical issues of biology and evolution. Image: Darren Naish.

Over recent years, Todd has been working closely with Jessica Carroll in her development of the Cassowary Conservancy of North America (CCNA) in Fort Pierce, Florida. A plan to collect and transport a number of cassowaries, kept in a private collection some short distance from CCNA, finally came to fruition in the early weeks of 2023. Nine full-grown adult cassowaries (belonging to at least three different taxonomic forms) had to be captured, boxed, transported, and moved to new premises. The whole operation had to occur within the timeframe of about a week (due to schedules), and the entire thing needed to occur in a specific part of January since this is when the weather is most amenable and also before the birds are carrying shelled eggs.

Caption: cassowaries (this is a yellow-necked northern cassowary) are fascinating from just about every angle. The remarkable colours of the head and neck are obvious enough, but note also the wing quills, the flattish top to the casque (not present in southern cassowaries), and how close the feet are held when the bird is standing. Cassowaries also have an impressive gape and cavernous mouth. Images: Darren Naish.

Needless to say, seeing the capture and transportation of nine cassowaries would be something of an unusual event: a unique one, in fact. Would I be able to come along? It would be tricky since my schedule isn’t exactly sparse, but I succeeded – after numerous shenanigans and a lengthy call with the United States Department of Homeland Security (err, long story) – in getting it arranged.

The need to have events filmed and documented (more on this in the near future) meant that we also needed people skilled in camera operation, and thus I also took along my daughter Hel, a film studies student with access to appropriate filming equipment.

Caption: Florida is something else if you’ve never visited before. For me, new habitats, landscapes and animals were everywhere. We drove past this ditch most days, and there was always something new here. The bird in the middle is a Limpkin Aramus guarauna. Image: Darren Naish.

So off to Florida and the CCNA we went, essentially for the trip of a lifetime.

Caption: portraits of a mature, gnarly female Southern cassowary. The bill in this individual is quite damaged and worn, and her nostrils are partly overgrown and slit-like relative to those of other cassowaries. Note also the coloured patches on the rear part of her lower jaw. Images: Darren Naish.

Cassowaries up close and personal. Cassowaries are, of course, potentially highly dangerous and must absolutely be treated with respect, though – like the majority of non-predatory animals – they don’t ordinarily go out of their way to seek conflict with humans. Their aggressive temperaments most likely stem from an evolutionary history of protecting territories with prolific fruit trees from other cassowaries. Safety and sensible behaviour were paramount at all times, we always kept a safe distance from the fences, and gates were latched and locked when birds were being corralled and transported (more on that in a moment). I never saw any aggressive behaviour from any of the cassowaries on the trip, bar one cassowary-cassowary interaction between a fence.

Six of the cassowaries concerned were kept together in pairs. Females are bigger than males and I had the impression (and it may not be a correct one) that females may perhaps have bigger casques and wattles. The science currently says that this is not the case (Green et al. 2022a), but further studies are coming. When people approach, the female asserts herself and gets up close to the fence while the male hangs back. If the male stands in a location that the female deems incorrect, she will scold him with a hiss and he will make whimpering noises before relocating.

Caption: typical positioning of a male and female Southern cassowary, with the larger, taller female seemingly taking the lead, as is typical. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: more images of a male and female southern cassowary pair, again showing the larger female taking the lead. Images: Darren Naish.

Most of us know that cassowaries are vocal, but getting the chance to hear the sounds they make are few and far between. I’m pleased to say that we heard the birds make a ton of noises. These included huffs, puffs and hisses, and deep rumbles and growls. It might not be well known – I’m not sure I knew this before going to Florida – that cassowaries very much respond to humans, so our approaching an enclosure often triggered them to start vocalising. On several occasions, those southern cassowary females living as part of a pair would seemingly need to express their dominance by doing a head-down, repetitive vocal display. The bird inflates part of its neck, points the bill down to the ground, and creates a series of deep, resonating, vibrating booming calls that are felt as much as heard. The plumage bristles as the bird does this.

Caption: this image (one from a sequence) shows a female Southern cassowary vocalising while sat on the ground. Her neck inflates, her plumage bristles, and her head moves back and forth as sound is broadcast outwards. Image: Darren Naish.

Richard and I suggested that pneumatic connections between the throat region and casque perhaps mean that birds engaging in this bill-down vocalising are using the casque as a resonator (Naish & Perron 2016). Subsequent work by Brassey & O’Mahoney (2018) and by Todd and colleagues too has shown this is incorrect (Green et al. 2022b), and indeed I’m now confident that the noises made in these events are emanating outwards from the cassowary’s neck and the anterior part of its chest, not from the casque alone.

Caption: in this series of images (stills from a video sequence), this female Southern cassowary is performing a ‘snap-huff’. A series of short, deep, growling huffs were issued (timed with neck inflation and bristling of the plumage), each sound ending with a rapid snap or clap of the jaws. Images: Darren Naish.

Now we come to Liberace the red-necked northern cassowary. Liberace is a very beautiful, flamboyant, brightly coloured cassowary who – like his human namesake – is something of a shameless show-off. His response to the arrival of people is to look straight at you with wide, bright eyes and engage in a prolonged loud braying, his mouth wide open.

Caption: Liberace the red-necked northern cassowary, here issuing a loud, repetitive braying call. His cheek flanges, green patches on the casque and single wattle are obvious here. Images: Darren Naish.

I had no clue that cassowaries did this until Todd first showed me a recording. We were lucky enough to see and hear Liberace do it several times during the trip. I’ve since seen recordings of other red-necked northern cassowaries doing this and it seems that all individuals call with slightly different intonations and pacing. One of the yellow-necked northern cassowaries in the group also performed this braying, though whether this is normal for yellow-necked northerns or learnt by this individual from Liberace is unknown and either is possible. There’s clearly a fruitful lot of work to be done on cassowary vocals and vocalising.

A whole lot of anatomy. Just getting to see cassowaries up close is a real treat; their anatomy is extremely complex, and numerous of the relevant details haven’t yet been properly described or analysed. The bill is complex, with serrated edges and asymmetrical tips that vary between individuals. Rugose and coloured nodules on the sides of the lower jaw appear to be additional display structures… as if the casque, carunculated head and neck skin, and wattles aren’t enough. At least some cassowaries have big fleshy cheek flanges.

Caption: cassowaries mostly walk with the body held approximately horizontally, with the head semi-horizontal or angled slightly downwards. In fact, they might rarely have reason to look up. But when confronting other cassowaries or other animals (including humans), they will deliberately stand tall. Note the heavily textured form of the casque in these two individuals. Images: Darren Naish.

Cassowary casques are not a monolith, being differently shaped in the different species and even differently patterned and coloured. Yes, they’re not all monotone grey; as you can see from the photos here, those of some northern cassowaries have greenish patches. Cassowary eyes are enormous and extremely obvious even at distance.

Caption: there’s a lot of interesting detail here (this is Liberace, a red-necked northern cassowary). Note the different colours of the different rhamphotheca sections and the green areas on the casque. His cheek flanges are obvious, and note also the orange patch on the nape. Images: Darren Naish.

The highly reduced cassowary wing is, of course, almost entirely submerged in the plumage, but the long, spike-like wing quills are not. They show that the wings are mobile and that the quills might have a role in display and signalling, since they’re held at different attitudes according to what the birds are doing. Todd brought my attention to occasions where the birds seemed to deliberately hold the quills out to the side in order to make noisy contact with vegetation or fences. Claims that the reduced forelimbs of cassowaries are relictual and non-functional don’t seem to be at all correct. Yes, this is relevant to my thoughts on how we portrayed the Cretaceous abelisaurid Carnotaurus in Prehistoric Planet.

Caption: images from a sequence that show Piggy (a yellow-necked northern cassowary) approaching a fence, and deliberately raising and flaring his wing quills as he does so. Images: Darren Naish.

In short, it’s obvious that there’s still a huge amount of work to do on cassowary anatomy.

Boxing and transporting cassowaries. Cassowaries of course have a reputation of being murder-death-kill machines, the idea being that one might run up and stab you repeatedly in the nethers should you have the audacity to enter its territory. A few videos online create the impression that capturing a cassowary might involve running to and fro, lots of shouting and pointing, and repeated leaping attacks from an infuriated giant bird.

But… no. Those videos involve distressed birds that were deliberately riled up for the camera. In all cases the birds did the thing that virtually all animals do when people approach quietly and calmly, which is to move away quietly and calmly and maintain a safe distance.

Caption: specially constructed boxes were used in containing and transporting the birds. They served us well and everything went to plan. Image: Darren Naish.

Todd and Jessica employed a sensible and highly efficient technique of capturing, boxing and transporting cassowaries. It involves experienced people, large wooden shields (essentially big sheets of wood with hand-holds, used to maintain a barrier between human and bird), and specially made wooden boxes that have hinged doors and brackets on the side to allow lifting via metal poles. The entire process starts with the box being placed in a corner of the enclosure. The job is then to get the cassowary into the box with minimal stress. Although the adult cassowaries at the CCNA have not been previously taught, some zoos crate-train their cassowaries with food rewards to prompt them into boxes without contact of any kind.

Caption: Todd and Jessica usher Liberace the northern cassowary into a crate using specially designed shield-like boards. Image: Todd Green, used with permission.

Caption: another image of cassowary capture. At this point in the process, the bird has no option but to enter the crate, and most of the cassowaries did indeed co-operate. Image: Todd Green, used with permission.

How, exactly, did the whole thing go with this relocation effort? Everything was kept quiet and calm, with no swift or unpredictable movements, as Todd and Jessica moved into and around the enclosure, gradually ushering each bird towards the respective box. Where possible, a corral was used to guide the bird into the box. Some cassowaries went into their boxes with minimal persuasion; others realised at the last second that they didn’t like boxes, and then ducked down and bolted away at surprising speed, or even climbed and leapt right over the shields and the people holding them. Yes, I have seen a cassowary gain purchase on a shield and adjacent fence, and climb and leap clear over Todd’s head (who is six-foot tall to give you some perspective).

These few, intense seconds were every bit as dynamic and jaw-dropping as you’d expect, but it’s important to recognise that they were exactly that: a few, intense seconds in what was otherwise a calm, efficient and quiet undertaking. Each entire capture event (as in, from when people entered the pen to when they left with a bird in a box) took 15 to 20 minutes, with just one taking about 30.

Caption: after being transported and then taken to their new premises, the cassowaries were often a bit reluctant to leave their crates. But they generally did so in fairly slow and sedate fashion. Image: Darren Naish.

Feet and footprints. After the captures I would wander round the enclosures and inspect the mud to see if any good footprints had been left. On several occasions they had, and I took the best photos I could. Cassowary feet are amazing, but a few details are of special interest. The tubercles on the foot’s plantar surface leave chainmail-like impressions in the mud, and the tips of the third and fourth claws leave neat and prominent holes (cassowaries have three toes, but the first toe – the hallux – is absent, meaning that the three are digits II, III and IV).

Caption: cassowary prints left in the soft soil of their enclosures. The left-hand image shows a right foot, and the right-hand one a left foot. As you might predict for animals of heavily wooded, often tropical or subtropical places, cassowaries are very comfortable on soft surfaces and have no trouble with mud and muddy pools. They may even deliberately seek out forest pools for wallowing. Images: Darren Naish.

The massive digit II claw comes to a sharper point than seems typical for captive cassowaries, and indeed for the museum specimens I’ve seen (virtually all of which were kept for a time in captivity before their remains joined a zoological collection). Todd reckons that this is a consequence of a life spent walking on soft substrate, which makes sense, and we presume that the pointy-clawed condition is the case in wild birds too. Could wild-living cassowaries be more dangerous than captive ones for this reason? I guess having sharper-tipped digit II claws would make you more of a dangerous stabber, but I don’t know that the difference would count for all that much.

Anyway… with the bird in the box, we transported it (lifting it via the metal poles) out of the enclosure and, ultimately, on to the flatbed of Jessica’s truck. There was then the required drive to the CCNA, and then unloading at the opposite end where the birds were introduced to their new accommodation.

Caption: at left, southern cassowary in a crate (note the double wattles). At right: Liberace in a crate. Images: Darren Naish.

Chicks and life with humans. The final thing I want to talk about concerns chicks. The CCNA is home to a number of cassowary chicks as well as adults. The chicks are cautious but moderately friendly animals that like to hang out in small groups if they can, and I can easily believe that one could bond with you and become a life-time companion should you put the time and effort into it.

Caption: southern cassowary chicks with ever-present decomposed dung pile. They seem to generally accept humans as members of their social group, so long as there are no surprises or scary movements. Image: Darren Naish.

Yes, life-time: these are long-lived birds that can persist into their sixth decade if conditions allow. I should add here the usual caveat that birds that bond with humans often do so because the birds see the person as a sexual partner, and here's another interesting question: are cassowaries more prone to bonding with, or responding to, people than other birds are because humans (especially humans with dark skin or clothing) are especially similar to cassowaries… superficially, of course.

Caption: I cannot get bored with these birds, they are incredible. Cassowaries themselves might think of us as slightly unusual members of cassowary kind. Keep this in mind when imagining a hypothetical zoo housing non-bird dinosaurs. At least some such animals would likely become sexually fixated on humans. Images: Darren Naish.

I should also add that cassowary chicks and adults are regular coprophages, picking apart and eating dung at what seems like every opportunity. This could be because rapid transit time means that cassowary dung often contains relatively undigested plant food (and getting it from dung is likely easier than getting it straight from the source), or because youngsters need to obtain their gut flora from adult dung, or both.

And that about wraps things up for now. More news on cassowaries is set to appear soon, with many things going on in the background.

Caption: Liberace (the red-necked northern cassowary discussed above) inside a crate, and looking fairly relaxed about it. Image: Todd Green, used with permission.

Travelling to Florida and seeing these birds up close was an incredible experience for me and I’m so grateful to have had the opportunity. I learnt so much, and had so many unique experiences. Massive thanks to Todd for getting me involved and for his time, assistance and co-operation, thanks to Hel for the work with filming, and thanks also to Jessica and others for all their work and hospitality.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on cassowaries, see….

Walter Rothschild and the rise and fall of Sclater’s cassowary, February 2011

Did dinosaurs and pterosaurs practise mutual sexual selection?, January 2012

Controversies from the world of ratite and tinamou evolution (part I), March 2014

Inside the Cassowary's Casque, Updated for 2022, April 2022

Refs - -

Elliason, C. M. & Clarke, J. A. 2020. Cassowary gloss and a novel form of structural color in birds. Science Advances 2020; 6 : eaba0187.

Green, T. L. & Gignac, P. M. 2023. Osteological comparison of casque ontogeny in palaeognathous and neognathous birds: implications for selecting modern analogs in the study of cranial ornaments from extinct archosaurs. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society doi: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlad016

Green, T. L., Kay, D. I. & Gignac, P. M. 2022a. Intraspecific variation and directional casque asymmetry in adult southern cassowaries (Casuarius casuarius). Journal of Anatomy 241, 951-965.

Green, T. L., Watanabe, A., Ng, J., Chariwala, S., Goldblatt, T., & Gignac, P. 2022b. 3D cranial imaging is the swan song for the cassowary casque as a vocal resonator. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts, 2022, p. 165.

Mack, A. L. 2013. Searching for Pekpek: Cassowaries and Conservation in the New Guinea Rainforest. Cassowary Conservation & Publishing, New Florence (PA).

McInerney, P. L., Lee, M. S. Y., Clement, A. M. & Worthy, T. H. 2019. The phylogenetic significance of the morphology of the syrinx, hyoid and larynx, of the southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius (Aves, Palaeognathae). BMC Evolutionary Biology 19, Article number 233.