Welcome to the third part in this lengthy series of articles, all of which are devoted to the argument that those Mesozoic faunas inhabited by multiple sauropod taxa – in particular those of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation – have too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!). You need to have read parts 1 and 2 for this to make sense. Those articles set up the TMDD contention, and then showed why arguments relating sauropod diversity to Paleogene mammal diversity are erroneous. In this article, we look at another mammal-based argument.

Caption: a Morrison diplodocid montage. Clockwise from far left: Brontosaurus excelsus at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History; the absurd neck of Barosaurus at the Royal Ontario Museum; the relatively diminutive Kaatedocus siberi at the IRSNB, Brussels. Images: Ad Meskens, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); KristyVan, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Paul Hermans, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

‘Neontological species’ are a red herring here. Prothero (2019) didn’t just compare the high diversity of Morrison Formation sauropods with that of Paleogene mammals. He also implied that modern giraffes – as in, the long-necked Giraffa giraffes – might in some way serve as Morrison sauropod proxies. Ok, this argument is rather… involved, so bear with me as we go on a somewhat lengthy diversion.

Caption: oh my god, how many times have giraffes been featured at TetZoo now? Too many times, I think. At left: a captive Rothschild’s-type giraffe on show at Colchester Zoo, UK. At right: a famous photo showing Bernard Grzimek investigating a sadly deceased Maasai giraffe. Images: Darren Naish, (c) BBC.

Until recently, it was widely assumed that all living giraffes belonged to the same single species (Giraffa camelopardalis), albeit one consisting of between 7 and 12 subspecies, depending on who you listen to. Since about 2006, however, it has increasingly been argued that at least some of these supposed ‘subspecies’ – between 2 and 8 of them – should be elevated to species rank, since molecular data shows that the ‘subspecies’ are genetically highly distinct, lack evidence of hybridisation (though read on), and have – in cases – been separate for more than 1.5 million years (Brown et al. 2007, Hassanin et al. 2007). It should be added that these different sorts of giraffes look different from one another, most notably in the pattern, form and extent of their blotches. There’s also some variation in body size, and in the form and proportional size of their median horns (though read on). Giraffe species-level taxonomy has been the topic of extensive debate, by the way. Don’t go thinking that the multi-species idea has been accepted unconditionally, with open arms (see Bercovitch et al. 2017, Fennessy et al. 2016, 2017, Petzold & Hassanin 2020).

Caption: there aren’t that many books which give you detailed insider info on giraffes, but these three are a start. Image: Darren Naish.

Prothero initially said (both in his 2015 blog article and in his 2019 book) that there’s only one species of giraffe across the whole of Africa. Ergo, here’s evidence for TMDD!, since – so the argument goes – how can there be lots of contemporaneous Morrison sauropods when there’s only one giraffe? But on considering that there are now thought to be some or many giraffe species – an issue perhaps brought to his attention by a reviewer (who might have been me) – he wrote “Even if there are several different species of giraffes, they live in ranges that do not overlap in Africa, so you would never find two different species in the same place as is claimed for Morrison dinosaurs” (Prothero 2019, p. 111).

I personally do think that the multi-species model for living giraffes is the way to go (I’ve been writing about it since 2006: here’s a TetZoo ver 1 article on it). But it’s important to note that ‘neontological species’ of this sort – these various giraffe populations previously regarded as ‘subspecies’ – are not comparable to ‘palaeontological species’ of the sort we recognise for Morrison sauropods. We can’t do genetics on sauropods, we can’t see whether they differ based on their colours and skin patterns, and we don’t have a good handle on their geographical ranges or hybridisation patterns.

Caption: giraffe skulls are variable, but are they really variable? Well, not really. The main variation concerns how much ossification there is on the top of the skull and the size of the median horn. Mihlbachler et al. (2004) figured this selection of skulls to depict giraffe skull variation. Image: Mihlbachler et al. (2004).

By taking enough measurements from enough giraffes, we can find what looks like osteological variation between the various populations (particularly in the size of the median horn). Groves & Grubb (2011) did this when supporting the existence of 8 living giraffe species. This variation, however, is only obvious in some populations, is often only obvious in mature males, and involves extensive overlap between the populations (Groves & Grubb 2011, p. 64, pp.68-70). It’s exactly the sort of variation that – if found in a fossil species – would be interpreted as intraspecific, or as clinal. Indeed, Mihlbachler et al. (2004) drew attention to this variation as the sort that was considered ‘acceptable’ within a species (they were writing with the ‘single species’ paradigm for giraffes in mind).

Caption: recent studies have led to the naming of several new Morrison Formation diplodocid species and genera, and the reidentification of specimens previously assumed to be Diplodocus or Apatosaurus. This skull (AMNH 969), on show in New York, was long thought to belong to Diplodocus but is now referred to Galeamopus. Image: Ryan Somma, CC BY-SA-2.0 (original here).

But this is nothing like the sort of variation that has allowed us to recognise distinct Morrison sauropods. Hey, Barosaurus and Diplodocus don’t just differ in that one has a higher bump on its skull than the other. They differ in the number of vertebrae they have, in the proportional length of the forelimbs, and in just about all aspects of caudal anatomy you can think of (McIntosh 2005). Similarly, Brontosaurus and Apatosaurus don’t differ in ways that can be linked to ontogenetic or sexual variation: they differ in the detailed anatomy of their vertebrae (as in, concerning the proportions of the neural spines, the distribution of bony laminae and so on), in the shape and detailed anatomy of the scapula, and in the proportions of the astragalus (Tschopp et al. 2015). Note that I’ve picked especially similar Morrison sauropods here. The differences between other taxa are more profound.

Caption: are Morrison Formation diplodocids - like the diplodocines Barosaurus lentus (at top) and Diplodocus carnegii, shown here - similar enough to be intraspecific? The anatomical differences are pretty profound, more than what you’d expect within a species. Image: (c) Greg Paul.

If you’re observant – or nit-picky, take your… pick – you’ll have noticed that I just compared species (the giraffes) with genera (the sauropods). If we look at the anatomical details used to distinguish Morrison sauropod species – the species of, say, Brontosaurus – we find long lists of vertebral peculiarities, features relating to the precise shapes of ribs, limb bones and pelvic girdle bones, and so on (Tschopp et al. 2015). In other words, we’re dealing with mostly precise detailed differences that exceed the vague, shape-based variation reported for giraffes (Groves & Grubb 2011).

My point here: the relevant sauropod taxa are more different in bony anatomy that are living giraffe species.

Caption: a group of captive giraffes at Marwell Wildlife, UK. Most captive giraffes are hybrids between Rothschild’s or Nubian giraffes and Reticulated giraffes - these are - and hence many have now been sterilised to prevent further breeding. Look for the individual lacking most of its tail. Image: Darren Naish.

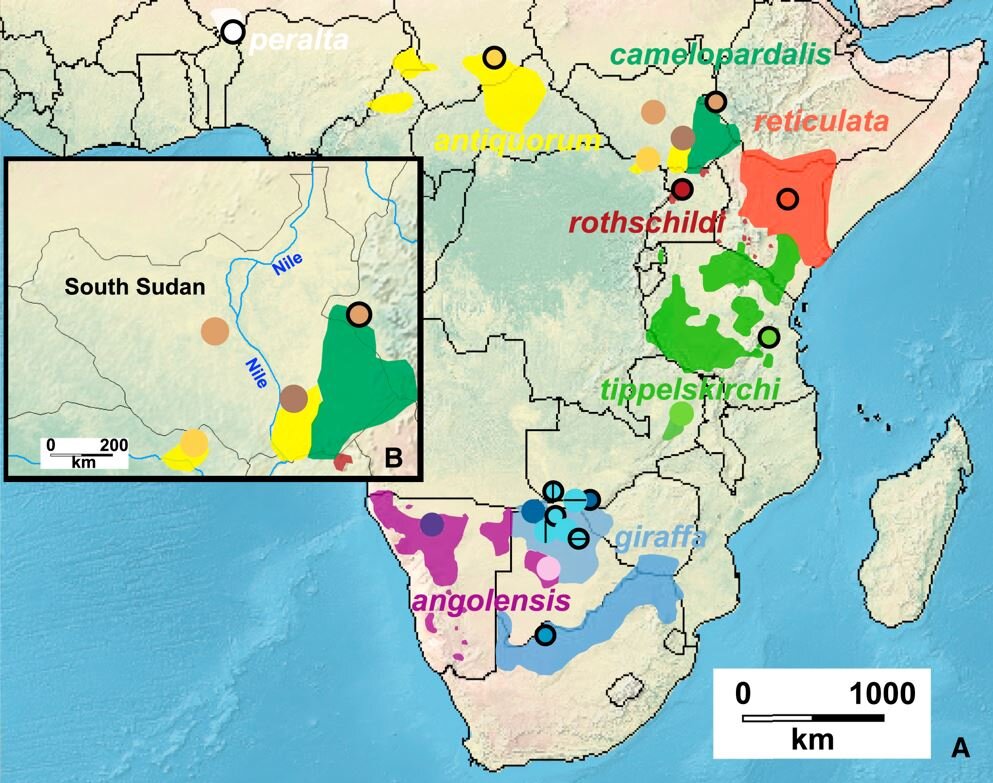

What about Prothero’s argument that the different giraffes “live in ranges that do not overlap in Africa, so you would never find two different species in the same place as is claimed for Morrison dinosaurs” (Prothero 2019, p. 111). This isn’t quite right. A few wild giraffes are on record which looked like intermediates between Reticulated giraffes G. reticulata and Maasai giraffes G. tippelskirchi, and between Reticulated giraffes and Nubian giraffes G. rothschildi (Groves & Grubb 2011), and hybridisation between these taxa – in the wild – has been confirmed by genetics (Brown et al. 2007, Petzold & Hassanin 2020). Furthermore, saying “but they all live well apart” is an over-simplification… or, to be less polite, is wrong… seeing as there are several areas where the taxa butt right up against each other, or even have overlapping ranges (Fennessy et al. 2016), and thus could – theoretically – be discovered as fossils in the same quarry. And…

Caption: range maps of the different giraffe taxa reveal several places where the ranges butt up against one another, or even overlap. Image: Fennessy et al. (2016).

Caveat 1: we’re talking here about the modern ranges of these giraffe taxa, when the number of giraffes is a whole lot less, and the distribution of giraffes is a whole lot smaller and more fragmented, than was the case just a few centuries ago. Of incidental interest is that Petzold & Hassanin (2020) discussed how members of some giraffe taxa likely crossed distances and hybridised with adjacent taxa during the Pleistocene.

Caveat 2: we’ve become bogged down here in a discussion of species within a morphologically conservative genus. Even if there is only one giraffe species, how does this counter the idea of there being multiple Morrison sauropod genera? Giraffes live alongside a list of other artiodactyls and big megamammals, and prior to the Holocene they lived alongside an even greater range, among which were additional giraffe species!

Let’s wrap this up. Does the diversity of giraffes tell us anything whatsoever about the diversity of Morrison Formation sauropods? Prothero’s (2019) main point – he was seemingly inspired by Mihlbachler et al.’s (2004) discussion of morphological variation in giraffes – was that giraffe variation could be a proxy for sauropod variation; that the existence within the ‘one species’ Giraffa camelopardalis of a fair bit of variation could show that the variation seen within Morrison sauropod species and genera might actually just be members of the same one genus, or even species. But however many giraffe species there are, the fact is that the variation reported for them thus far is substantially and dramatically less than that reported for Morrison Formation sauropod species and genera. Bottom line: giraffes do not in any way help show that there are too many damn dinosaurs. If anything, the fact that what was long thought to be a morphologically conservative ‘species’ turns out to be several renders it possible that our view on how many sauropods there really were is a conservative under-estimate, since fossils only give us bony anatomy to go on. That, however, is an issue for another time.

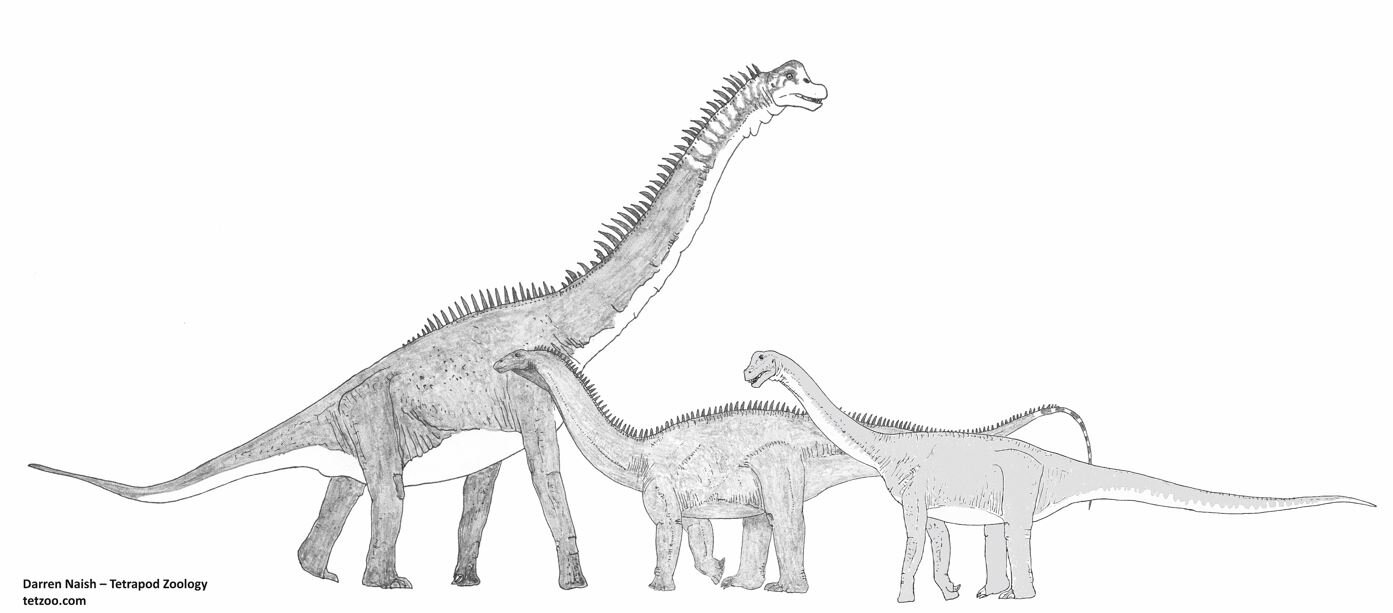

Caption: it’s become obvious to me that I don’t have sufficient illustrations of Morrison sauropods. I need to do more. This montage shows a brachiosaur, apatosaurine and camarasaur. As usual, these illustrations were produced for my in-prep textbook. Image: Darren Naish.

That was a lengthy and unexpected diversion, but it’s at least relevant to a topic – giraffe species-level diversity – that’s been covered here at TetZoo a few times before. Come back soon for the next article in this series, there’s a lot more to get through yet.

For the previous article in this series, see…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 1, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2, April 2020

For previous TetZoo articles on sauropods, brontotheres, giraffes and related issues (linking where possible to wayback machine versions), see…

Giraffes: set for change, January 2006

Biggest…. sauropod…. ever (part…. I), January 2007

Biggest sauropod ever (part…. II), January 2007

The hands of sauropods: horseshoes, spiky columns, stumps and banana shapes, October 2008

Thunder beasts in pictures, March 2009

Thunder beasts of New York, March 2009

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures, May 2009

Inside Nature’s Giants part IV: the incredible anatomy of the giraffe, July 2009

Testing the flotation dynamics and swimming abilities of giraffes by way of computational analysis, June 2010

Paul Brinkman’s The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush, March 2011

The sauropod viviparity meme, May 2011

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part I), December 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part II), January 2012

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, February 2012

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012), November 2012

That Brontosaurus Thing, April 2015

Unusual Giraffe Deaths, November 2015

Burning Question for World Giraffe Day: Can They Swim?, June 2016

10 Long, Happy Years of Xenoposeidon, November 2017

The Life Appearance of Sauropod Dinosaurs, January 2019

Refs - -

Bercovitch, F. B., Berry, F. S. M., Dagg, A., Deacon, F., Doherty, J. B., Lee, D., Mineur, F., Muller, Z., Ogden, R., Seymour, R., Shorrocks, B. & Tutchings, A. 2017. How many species of giraffe are there? Current Biology 27, R136–R137.

Fennessy, J., Bidon, T., Reuss, F., Kumar, V., Elkan, P., Nilsson, M. A., Vamberger, M., Fritz, U. & Janke, A. 2016. Multi-locus analyses reveal four giraffe species instead of one. Current Biology 26, 2543-2549.

Fennessy, J., Winter, S., Reuss, F., Kumar, V., Nilsson, M. A., Vamberger, M., Fritz, U. & Janke, A. 2017. Response to “How many species of giraffe are there?” Current Biology 27, R137-R138.

Groves, C. & Grubb, P. 2011. Ungulate Taxonomy. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Hassanin, A., Ropiquet, A., Gourmand, B.-L., Chardonnet, B. & Rigoulet, J. 2007. Mitochondrial DNA variability in Giraffa camelopardalis: consequences for taxonomy, phylogeography and conservation of giraffes in West and central Africa. Comptes Rendus Biologies 330, 173-183.

McIntosh, J. S. 2005. The genus Barosaurus Marsh (Sauropoda, Diplodocidae). In Tidwell, V. & Carpenter, K. (eds) Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press (Bloomington & Indianapolis), pp. 38-77.

Mihlbachler, M. C., Lucas, S. G. & Emry, R. J. 2004. The holotype specimen of Menodus giganteus, and the “insoluble” problem of Chadronian brontothere taxonomy. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 26, 129-135.