If you’re a long-time reader of TetZoo, you’ll know that I’ve often examined and discussed the backstories to famous monster photos. And if you follow me on Twitter (I’m @TetZoo), you’ll know that I’ve lately been posting extremely long threads wherein I do likewise. It’s fun and results in lots of interaction. Today, I’m going to conduct an experiment and publish a monster-themed article here at the blog AND a threaded version of the same text at Twitter.

Caption: one of the most frequently seen versions of the flipper photos. At right, my attempt (from childhood) to draw it as I interpreted it. We were all led to believe that it really was a flipper, perhaps surrounded by foaming water…

On this occasion, we’re going to look at the so-called Loch Ness Monster FLIPPER PHOTOS of 1972. Here we go…

During the late 1960s and early 70s, it was seriously believed by a large group of people – affiliated as the Loch Ness Phenomenon Investigation Bureau or LNIB (it went by other names over the years) – that camera-led vigils at Loch Ness would, at any time, lead to definitive proof of Nessie’s existence. This was also the time that the LNIB joined forces with another group: the US-based Academy of Applied Science (AAS), led by inventor and lawyer Robert Rines (whose name is very often wrongly written ‘Rhines’). Rines died in 2009. Rines became a little controversial later in the Loch Ness story, since some investigators looked into his background and found that he didn’t have the scientific history or credentials he said or implied he did, nor had he followed a conventional scientific career. I don’t, personally, think that this makes that much difference to the work he was involved in, but it does seem that he was guilty of ‘credential mongering’.

Caption: Loch Ness, a substantial body of water. Image: Darren Naish.

Whatever, AAS brought in funds, hi-tech equipment and the promise of proper science, the story promoted in several Nessie books being that ‘Big Science’ had arrived at Loch Ness at last. And thus now the finding of Nessie was but days away! The story behind the adventures of the time is told in many books, the most detailed account being that in the late Roy Mackal’s 1976 The Monsters of Loch Ness (Mackal 1976) (but, don’t get me wrong, it’s not an especially enjoyable or entertaining book, sorry). Some at LNIB thought that the joining of the AAS was great, others that it caused “a loss of control” and that “much of the scientific care … was cast aside” (to quote author and investigator Tony Harmsworth; Harmsworth 2010). Rines and the LNIB worked together with expert in high-speed strobe photography Prof Harold Edgerton of MIT (known since his days with Jacques Cousteau as ‘Papa Flash’) to equip the vessel Narwhal with sonar equipment (a Raytheon DC 725 unit) and a second boat (Nan) with an underwater camera and attached strobe light.

Caption: a 1970s scene on the loch. From left to right: Robert Rines, Martin Klein, Tim Dinsdale. Note the hi-tech gear in shot. Image: Dinsdale (1976).

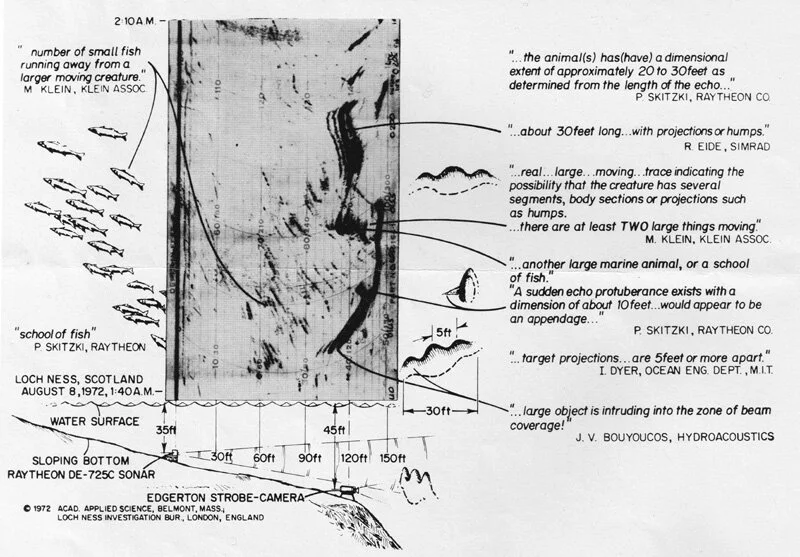

The equipment consisted of a 16mm time-lapse motion picture camera and a 50W strobe light, each housed in a cylindrical case. The camera was rigged to take a photo every 45 seconds (Nessie champions Tim Dinsdale and Nicholas Witchell said 15 seconds (Dinsdale 1973, Witchell 1974) and Mackal (1976) said every 55 seconds, but both seem to be wrong). On the night of 7th/8th August 1972, the two boats were 36m apart with the camera about 13m below the surface, pointed toward a deep valley and on or just above a submerged ridge. At several points between 1.40 and 2.10 in the morning, Narwhal detected sonar targets, interpreted as big animals. The traces sketched out by the Raytheon’s three styluses (the traces are shown here, as released by the AAS and LNIB in 1972) were said to demonstrate the presence of these big animals, and show that they had dorsal humps and large projections on the body (like… limbs). We’ll come back to all of this stuff in a moment, it’s problematic.

Caption: the sonar chart - with annotations from the AAS/LNIB team - corresponding to that section of the morning of 7th/8th August 1972 when supposed sonar contact was made with two large Loch Ness animals. This image (depicting the original printed sheet, designed for release to the press) is from Dick Raynor’s page on the sonar data.

The photos are obtained. 2000 photographic frames were exposed across the relevant time, and such was their perceived importance that they were immediately rushed to the US and developed the next day by Eastman Kodak. They were seemingly developed under strictly controlled conditions (this is known as being ‘developed under bond’, I think) which prevented any chance of fraud, confusion or their being accidentally mixed with other prints. Three seemed to show objects. These three photos were said to have been taken at the same time as sonar contact with the supposed objects was made, though it’s never been stated how this was established since the images weren’t time-stamped.

Thanks to commentary penned by Witchell (1974, 1989*), we know a fair bit about events specific to that night. Remember that the early 70s were an incredibly optimistic time for those involved in the hunt for Nessie, and Witchell wrote about these high spirits. “I well remember the boat crews’ excitement early on the morning of 8 August when they came ashore with the sonar chart which showed the activity below them”, he wrote (Witchell 1989, p. 145). There was then a wait “while the Academy [the AAS] went home to examine the film”, and a sense of excitement and accomplishment. “Surely, we thought, this would stir the scientific establishment”, Witchell (1974, p. 145) continued.

* Witchell’s book was first published in 1974 and at least four subsequent editions appeared. The relevant quotations appear in the 1989 edition, but not the 1974 or 75 editions (I’m not sure about the 76 or 82 editions, I don’t own them).

Caption: young Nick Witchell on the shores of Loch Ness. At right, the cover of one of the several editions of his book (probably the 1982 edition).

Members of the team at AAS included photography expert Charles Wyckoff (of Applied Photo Sciences) and sonar designer Martin Klein (of Klein Associates), in addition to Rines and Edgerton. Wyckoff – as photography expert – would have been responsible for part of the initial handling of the photographic prints. A big part of the flipper story is that the images were subjected to some sort of digital enhancement at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena. This was always described in fairly vague terms and certainly has that Big Science allure about it. We’ll come back to it, too, in a minute.

Caption: black and white versions of the two flipper photos, as shown in the usual (but technically incorrect) rotated view (they should actually be imagined rotated 180 degrees relative to what we see here). The versions shown here were included in Rines et al. (1976).

The photos came back and – eureka – they showed that Nan’s AAS camera had succeeded in photographing either two giant, diamond-shaped flippers (one in each of two photos), or the same flipper, captured at different angles in the two photos. We’ll come to the third photo later on, don’t forget it. Because the flippers were interpreted as being in focus (note my choice of words), they were taken to be at least 1.2 m from the camera, which meant that they had to be between 1.2 and 2 m long, or between 2 and 2.4 m long. The latter, surprisingly large size was favoured by Edgerton, JPL’s Alan Gillespie, and Nessie proponent Henry Bauer (Bauer 2002). However, Mackal (1976, p. 277) noted that “even the small sizes of the suggested range … seem too large to me”.

The photos are published. The photos (and the accompanying sonar evidence) were published on November 1st 1972 and appeared in Time magazine and numerous other press outlets. I’d always thought that media interest was high, but Witchell (1974) stated otherwise. Interest was low, perhaps because other Nessie photos had been released just 48 hours earlier by Frank Searle, an infamous character in Nessie history, linked with a series of often hilariously bad hoaxes. This wasn’t a coincidence. Searle knew that the AAS/LNIB team would be releasing its results and deliberately timed his announcement to scupper them.

Caption: Frank Searle (1921-2005) was quite the character, and his Loch Ness Monster photos were…. well, they were something else.

A meeting held at the British Museum (Natural History) (today the Natural History Museum), and attended by Rines and Dinsdale, apparently included announcement that the photos were definitely genuine ( … we’ll come back to this) but that the objects within them couldn’t be identified precisely. George Zug at the Smithsonian stated that the photos showed a “flipper-like appendage protruding from the side of a robust body” and Henry Lyman – Vice Chairman of the New England Aquarium in Boston – noted that the flippers didn’t look like those of a mammal and seemed to be something new to science. Peter Scott (not yet a Sir, his knighthood came in 1973) – a Nessie believer, brought into the fold by Dinsdale – produced diagrams showing how the flipper photos seemingly conformed to the anatomy of the giant, post-Cretaceous, humped plesiosaur he and his friends now believed in.

Caption: Scott and his colleagues imagined this specific look for the Loch Ness Monster. It was, in their view, a twin-humped plesiosaur (or, at least, plesiosaur-like animal) with a long neck, horns or breathing tubes on the head, and diamond-shaped flippers or paddles. Image: Darren Naish.

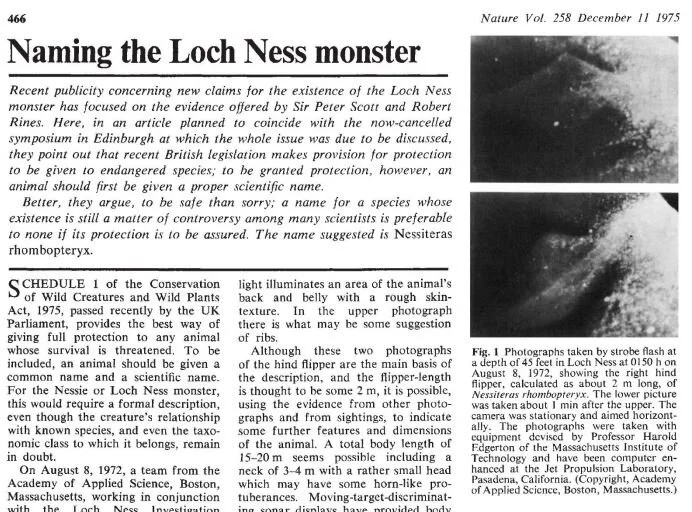

The photos and the naming of Nessiteras. Press interest might have been light, but the photos soon became a mainstay of published articles on the Loch Ness Monster. Indefatigable Nessie proponent and researcher Tim Dinsdale published an article in The Photographic Journal of April 1973 and argued that the flipper photo (he only discussed one of them) should be termed the ‘Rines/Edgerton picture’ and awarded the greatest significance (Dinsdale 1973). The flipper photos proved integral to Scott and Rines’ case of 1975 – published in Nature, no less – that Nessie was real, was a valid species which warranted conservation interest, and was deserving of a technical binomial name: Nessiteras rhombopteryx Scott & Rines, 1975 (Scott & Rines 1975).

Caption: the introduction to the infamous Scott & Rines (1975) article. Image: Nature Publishing Group.

Incidentally, the claim made by Gareth Williams in A Monstrous Commotion (reviewed here at TetZoo) – that the 1975 article was anonymous (Williams 2015) – is incorrect, as is evident not just from the article itself but from the follow-up correspondence, published in Nature in 1976, on which read on. Nessiteras rhombopteryx means ‘the Ness monster with diamond-shaped wings’, so here’s evidence that Scott and Rines bigged up the flippers as real and as a significant part of the animal’s biology. Incidentally, the beloved and oft-mentioned fact that Nessiteras rhombopteryx is an anagram of ‘Monster Hoax by Sir Peter S’ (Anon 1976) is a coincidence; Peter Scott had a long-standing serious interest in Nessie at this point, ‘believed’ in its existence, and was not in this for shits and giggles, as is confirmed by his other writings on the subject (Rines et al. 1976, Scott 1976a, b, c, 1980, 1987). Rines later argued that the binomial was also an anagram of ‘Yes, both pix are monsters R’.

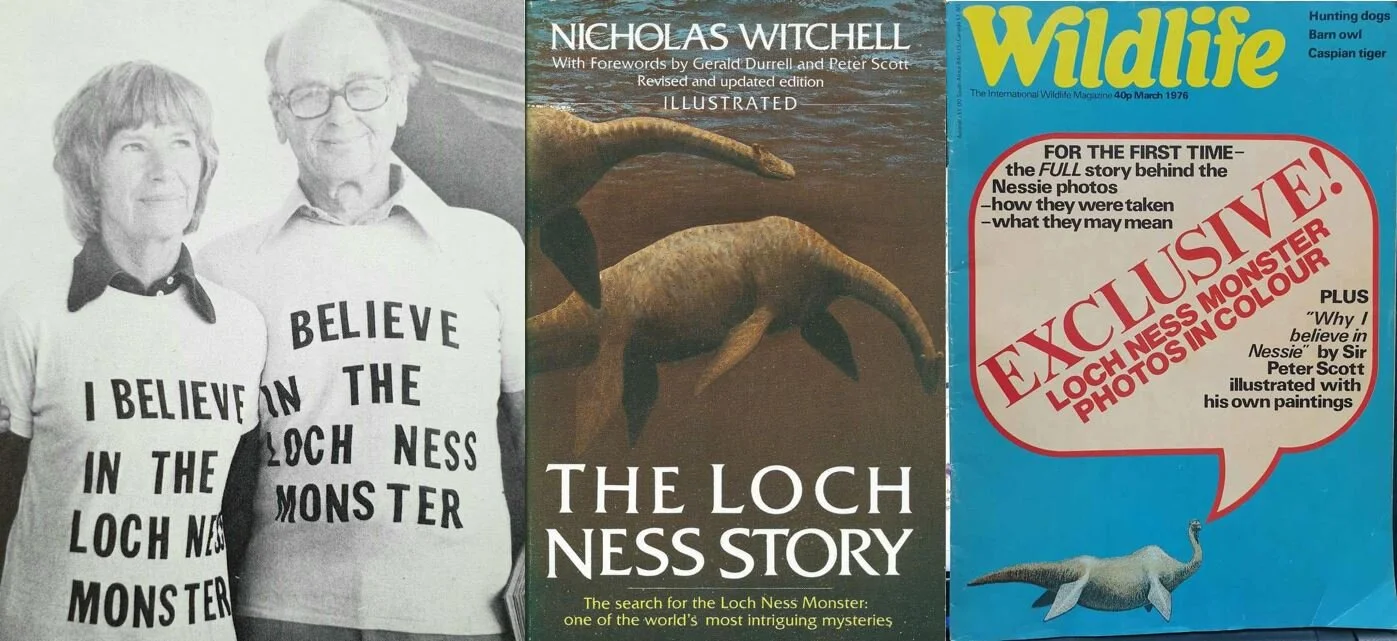

Caption: Peter Scott sincerely proclaimed his belief in the existence of the Loch Ness Monster, and stated this opinion many times in books and articles. He also painted Nessie many times, most memorably for the ‘courtship’ scene seen here on the cover of Witchell (1989). There are good reasons for thinking that Scott saw the monster as a motivator for the conservation work of the World Wildlife Fund, an idea explored in detail by Baynham-Herd (2020). The woman standing with Scott is his wife, Lady Philippa Scott.

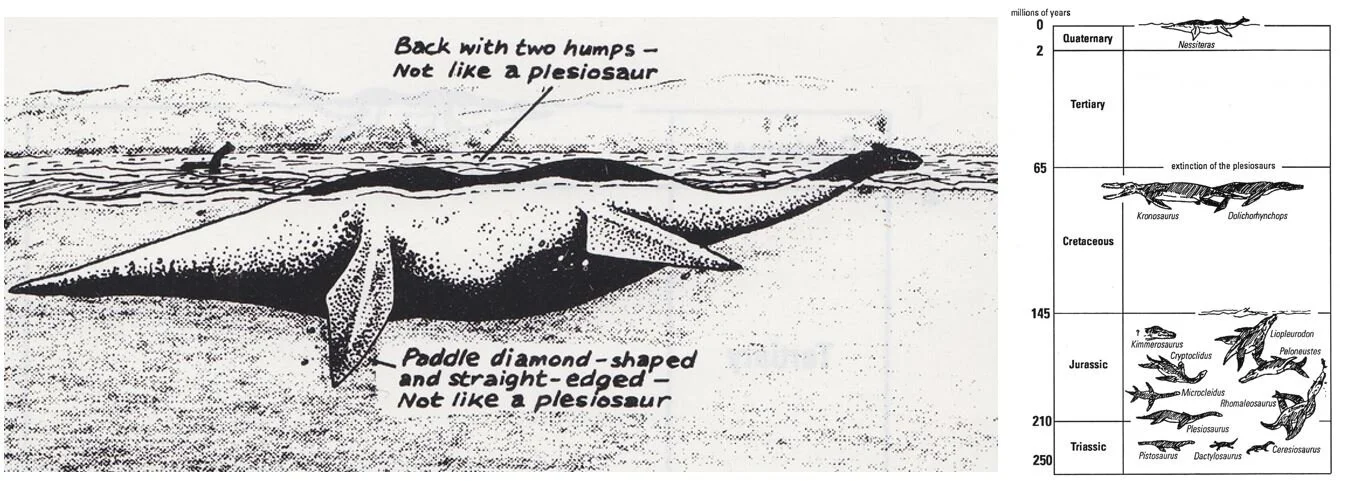

Post-1975 correspondence: to arms. Scott and Rines didn’t necessarily have an easy ride with respect to their Nature article, since, in January 1976, Nature devoted a full two pages to correspondence on it. Scotsman and vole expert Gordon Corbet at the then British Museum (Natural History) basically argued that the entire endeavour was sloppy, unsatisfactory and that naming the beast was a terrible decision (Corbet 1976). Scott (notably, without Rines) protested, arguing that sonar evidence backed up the veracity of the photos, and that a decision of “better safe than sorry” was the main motivator in publishing the binomial (Scott 1976b). In a second letter, palaeontologist (and sometime plesiosaur worker) Beverly Halstead, fellow palaeontologist Jennifer Middleton and ecologist Paul Goriup again took the paper to task. Halstead et al. (1976) objected to the implication that Nessiteras might be a plesiosaur, argued that plesiosaur limbs were utterly unlike the Nessiteras flipper, and proceeded with the bold and unusual claim that both the head and neck photographed in 1975 (I haven’t discussed those photos here; see my article on Gareth Williams’ book for more) and the flipper photos actually depicted parts of a submerged Viking ship. Alas, this suggestion was incredible, albeit (arguably) not as incredible as the claim that Nessiteras was real.

Caption: at left, Halstead et al.’s (1976) diagram, produced to show how the Loch Ness flipper differed from the wing-shaped limbs of fossil plesiosaurs. At right: the Collard plesiosaur, a specimen which has soft tissue outlines of its paddles preserved and thus informs us on the look of plesiosaur limbs (from Muscutt et al. 2017).

In his response, Scott (again, no sign of contributing authorship from Rines) argued that Halstead et al.’s (1976) proclamations about plesiosaurs ignored all sort of complexities and possibilities that might have arisen during plesiosaur evolution, and also that his 1975 paper had never included the word plesiosaur anyway, ha ha. Scott (1976c) went on to dispute the Viking ship suggestion, his main counterpoint being that the photos were taken in mid-water, not at the bottom… something that wasn’t entirely true (read on). But he was right that this was a pretty desperate suggestion.

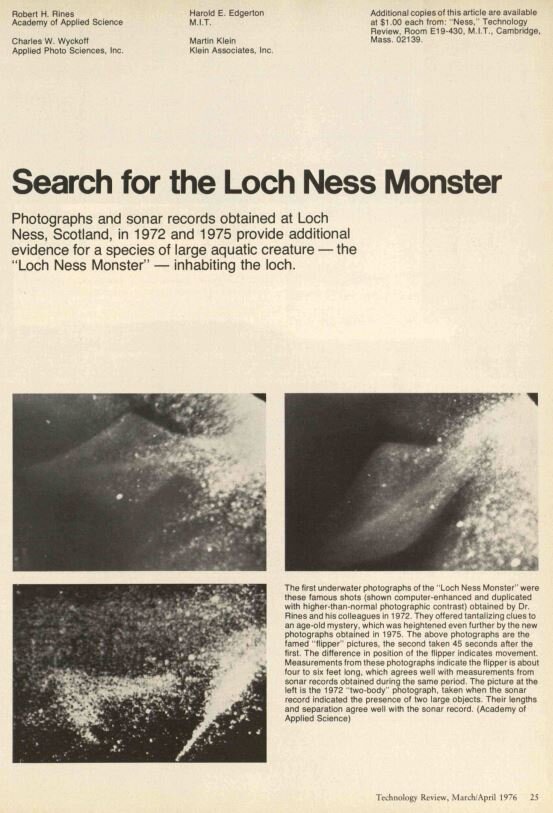

Rines published another technical article on the flipper photos, this one co-authored with Wyckoff, Edgerton and Klein in Technology Review in March 1976 (Rines et al. 1976). It described the whole Loch Ness endeavour and included numerous colour photos from the expeditions, as well as a list of supportive quotes on the significance of the photos from a range of experts, including Zug, marine reptile expert Christopher McGowan, palaeontologist A. W. (Fuzz) Crompton, London’s Peter Greenwood (an ichthyologist), dinosaur expert Alan Charig, and Peter Scott.

Caption: opening page of Rines et al. (1976). It shows both flipper images, plus the peculiar ‘third image’ (on which more later). This article marshalled support for the veracity of the flippers from an impressive cast of relevant experts.

Speculative Zoology comes to Loch Ness. Rather than simply being diamond-shaped and flat, the flippers were supposed to have a distinct structure: there was a thick central rib, a narrow leading anterior vane, and a much broader trailing posterior vane with a triangular prominence. The flippers are surrounded by deep shadow except on what’s interpreted as the dorsal surface and have very narrow bases. The differences between the two photos have been suggested to show that one’s a forelimb and the other a hindlimb, or that this is due to movement and hence differing angles of view (Bauer 2002). The anatomical configuration of the flipper or flippers isn’t seen in any tetrapod, and here we come to the speculative zoology part of this story. Scott and Rines (and Dinsdale and others too) thought (but never outright stated) that Nessie was a plesiosaur.

Caption: palaeontologist John Martin’s redrawing of Nessiteras, from Martin & Taylor (1990). At right, a whimsical geological sequence, showing the long gap between Cretaceous plesiosaurs and Nessiteras. A much larger version of this image was previously featured in the TetZoo review of Gareth Williams’ book on Nessie (go here).

We know from excellent fossils – some of which have their soft tissue outlines preserved (Muscutt et al. 2017) – that plesiosaur paddles were wing-shaped, not diamond-shaped, so a plesiosaurian Nessie would had to have undergone a lot of evolution relative to its fossil ancestors. Palaeontologists John Martin and Mike A. Taylor had fun with this idea in their 1990 book on plesiosaurs (Martin & Taylor 1990). Biochemist Roy Mackal, a prominent cryptozoologist and leader of many events at Loch Ness, compared the flipper shape with that of a wide range of vertebrates living and extinct and concluded that just about anything was possible since the Ness flippers didn’t have a special similarity with any one relevant animal in particular (Mackal 1976).

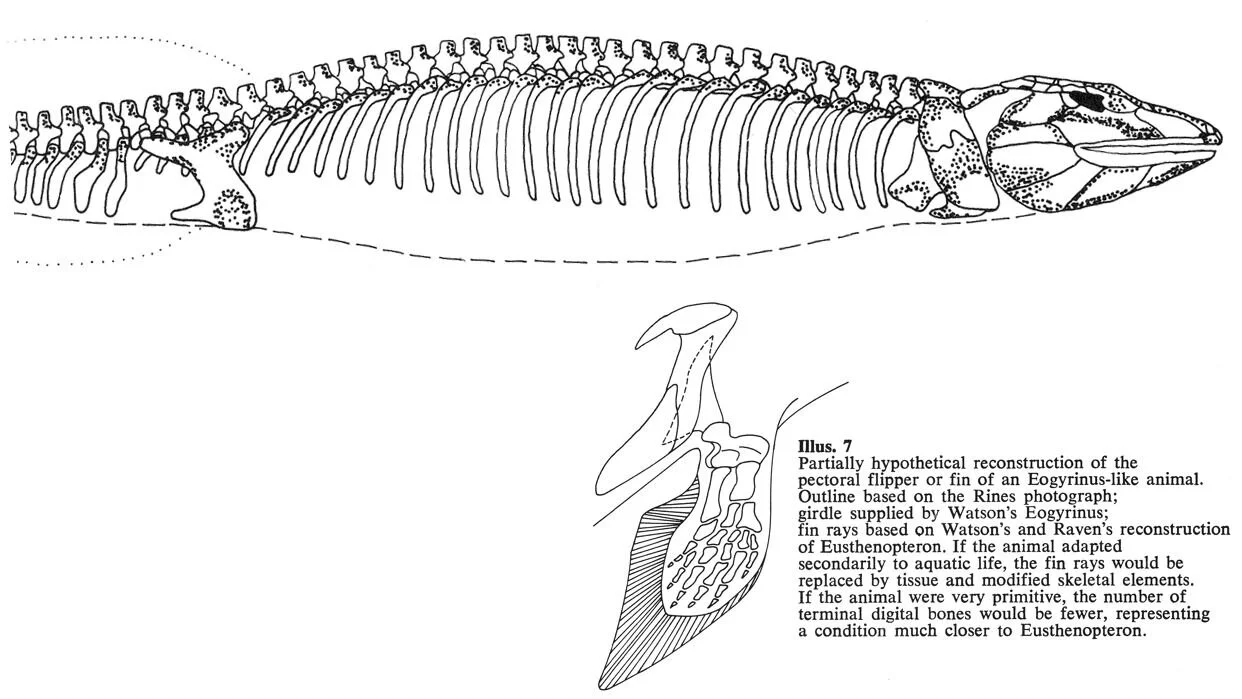

Caption: Mackal (1976) used this (at top) skeletal reconstruction of an embolomere from 1926 (originally published by D. M. S. Watson) to introduce his readers to this group (embolomeres have typically been described as ‘ancient amphibians’, but they’re not part of the clade that corresponds to Amphibia as we recognise it today). Below, we see the hypothetical embolomere limb Mackal depicted, kitted out with fin rays. Image: Mackal (1976).

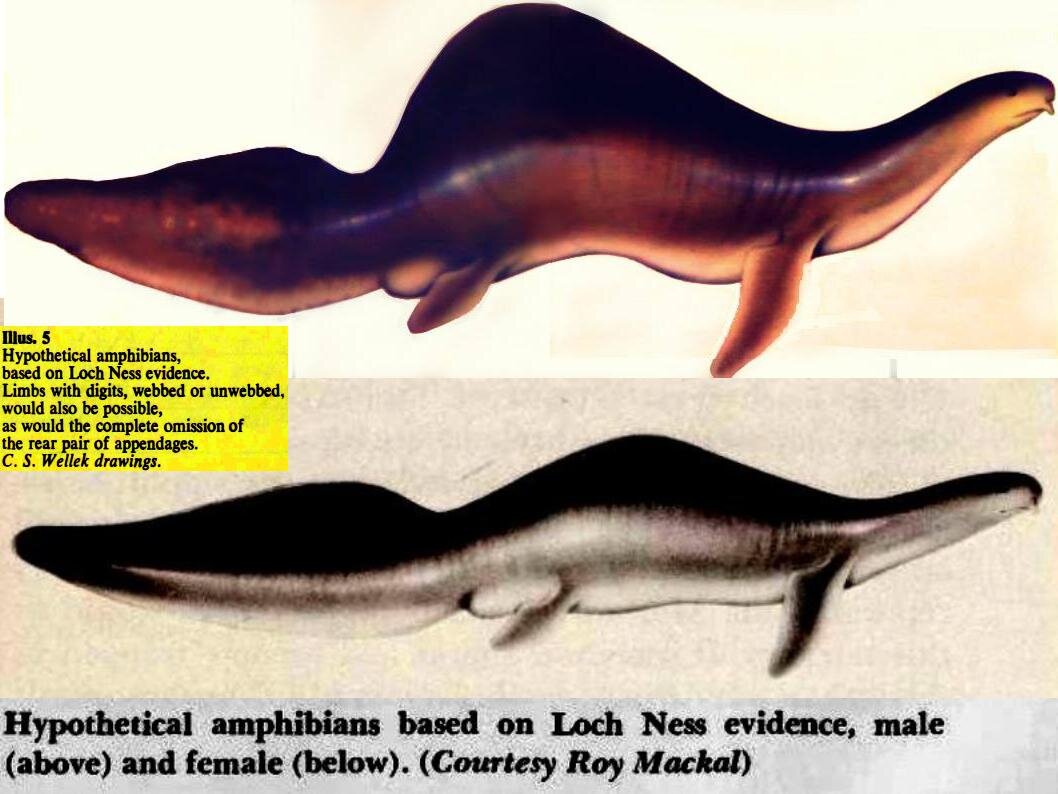

But Mackal was, for other reasons, especially fond of the idea that Nessie was a gigantic embolomere. Embolomeres are a group of long-tailed, mostly aquatic early tetrapods that supposedly died out in the Permian, around 280 million years ago. Mackal’s Loch Ness embolomere was a totally novel speculative animal, shaped something like a gargantuan newt but with flippers. C. S. Wellek brought this animal to life for Mackal’s book, and you can see that it has diamond-shaped flippers as per the 1972 photos. Mackal (1976) also featured a wholly speculative diagram, depicting how a fossil embolomere forelimb might correspond to either of the 1972 photos if only we give it imaginative fin rays… err, like those present in fish and not in embolomeres or other tetrapods, but ok.

Caption: a spectacular bit of SpecZoo… Nessie is a modern-day, enormous embolomere! Mackal’s 1976 book includes great artwork of this imaginary animal, but the best pictures are ruined by the book’s spine. Thanks to Scott Mardis for providing these versions of the illustrations. Image: C. S. Wellek/Mackal (1976).

Another zoological take on the flipper photos is that the flippers just don’t look like efficient organs of propulsion at all, since flippers mostly have a stiffened leading edge, not a (seemingly) floppy leading edge as per the objects in the photos. Loch Ness expert and author Adrian Shine suggested that the form of the flipper indicates that it might fold “on the forward stroke and [stiffen] on the backward stroke, the mechanism for which is not apparent” (Shine 1984, p. 70). He alternatively suggested that it would have to be rotated to function in propulsion, but his main take was that it likely wasn’t the main organ of propulsion at all, and that the flipper’s owner was most likely a tail-based animal (Shine 1984). He further noted that the flippers most resemble the fins of fish: in his view, the closest similarity was with lungfish fins, in particular those of the Australian Neoceratodus. This is why his article was titled ‘A very strange fish?’ (Shine 1984).

Caption: cover page of Shine (1984). At this point, the implication from Shine was that Nessie might still be a real unknown animal, but not a reptile as per Scott and Rines’ thoughts, nor a mammal as per Peter Costello and others.

There are no flippers here, only mud. OK, so far we’ve looked at interpretations of the photos which assume them to be the parts (the flippers or fins) of animals. But the thing is... this whole idea is bogus. The images don’t show flippers (or fins) at all.

Curious about the ‘computer enhancement’ used on the photos, a few researchers asked for, and obtained, the original (non-enhanced) versions. Let’s just say that they don’t look at all compelling. They show a greenish/greyish blurry mess, with little obvious detail. Here (below) is one of the originals. There’s a vague pale line in the originals, and an even vaguer series of lines (forming a rough rhomboid) around it. It seems most likely that we’re looking at the mud on the floor on the loch, marked with impressions made by a human-made object.

Caption: the original, unmodified ‘flipper photo’. There’s a feint diamond-shaped mark there, but if you see a flipper… well, good for you. Image: AAS.

At JPL in August 1972, the images were scanned and digitised. Seemingly, a computer programme worked out which pixels were deserving of enhancement. The results were the clear, clean-edged, diamond-shaped images you’ve seen elsewhere in this article. The work was done by Alan Gillespie, a grad student in geology who worked as a junior engineer at JPL. But it has since transpired – the story is told in most detail in Campbell (1986) and Harmsworth (2010) – that the images which Gillespie produced are NOT the famous diamond-flipper images at all.

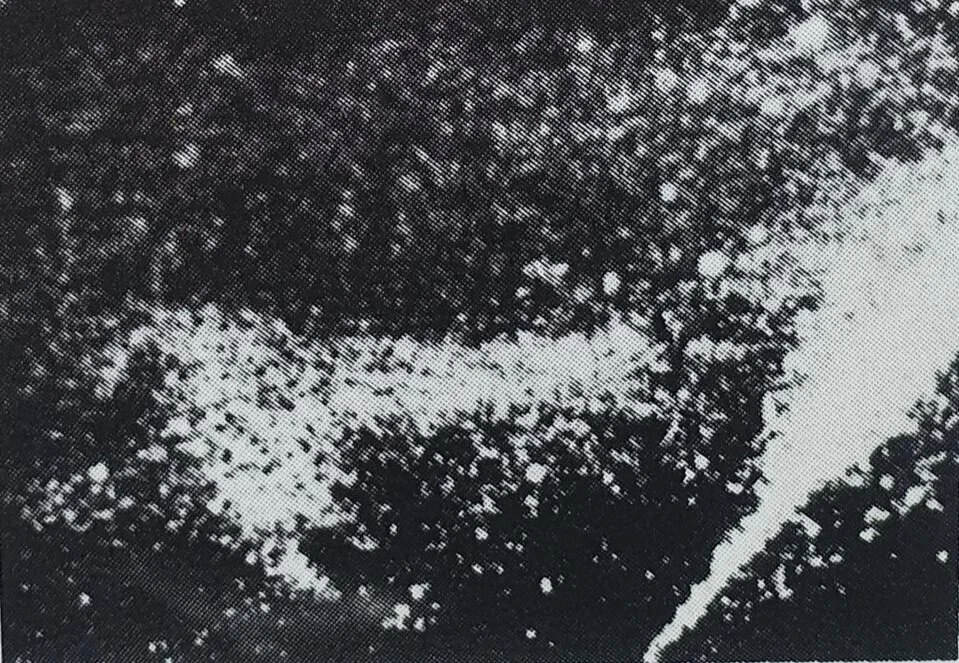

The actual enhancements don’t show diamond-shaped flippers, but messier, coarsely grained masses, lacking sharp edges (Harmsworth 2010, Williams 2015). Gillespie was asked for his take on events and confirmed that the clean-edged diamond-flippered images were nothing to do with him (Harmsworth 2010, p. 181). In 1984, both Discover and Skeptical Inquirer ran pieces saying that the clean-edged images had been retouched (not simply enhanced), and in a 2001 TV show Adrian Shine revealed that the clean edges of the clean-edged versions were not present in the originals: they’d been added, and seemingly by human hands, not computer enhancement. This retouching wasn’t done with an airbrush or anything especially fancy, but with a paintbrush, since the brush marks are visible on the photos (Harmsworth 2010, p. 181). Who was responsible for this?

Caption: the enhanced version worked on by Gillespie at JPL. This amorphous mass doesn’t look much like the clean-edged flipper we’re more used to. This version of the image comes from Williams (2015).

Wyckoff (who, you’ll recall, was responsible for the initial handling of the prints in 1972) was asked for his version of events, and in 1984 correspondence published in Discover denied that AAS ever released ‘retouched’ versions, his argument being that the sharp-edged look resulted from the fact that the images were composites which had been constructed by overlying different computer-enhanced versions (differing in sharpness and contrast) (Wykcoff 1984, cited in Bauer 2002). This doesn’t sound at all consistent with what Gillespie said, nor with the appearance of the enhanced version shown above. An interesting point made by Dick Raynor is that none of these ‘computer enhanced’ images (even the ones which Gillespie confirmed as those he worked on) exhibit any pixelation, as they really should for ‘computer enhanced’ images from 1972. Other Loch Ness images which underwent digital manipulation (like the Dinsdale film) show obvious pixelation. Were they ‘computer enhanced’ at all? I don’t know, it’s weird.

Caption: an inevitable component of cryptozoological stories is that many of the details and key observations are shared in popular books and magazines, not in technical literature. All cryptozoological investigators are, therefore, also book collectors. Harmsworth (2010) and Williams (2015) are among the more recent of Nessie volumes which those interested should obtain.

One idea is that this modification was done by a journalist who borrowed at least one of the photos before returning it to Robert Rines. When asked, Rines couldn’t say when, or whether, this happened. And it probably didn’t, since Rines sent Raynor a clean-edged (as in: retouched) version in October 1972: that is, before any journalists had had access to it. The retouching had been done at AAS. All of this was known by the mid-80s, yet the clean-edged versions continued to be used, and promoted as original (albeit ‘computer enhanced’) all the way up to 2007 at least (when Rines used one of them on the cover of his expedition literature).

What the photos most likely show is not just mud on the loch floor, but the mark made by the camera rig as it touched the bottom and disturbed the silt there. I owe this explanation (I included it in Hunting Monsters; Naish 2017) to Dick Raynor who described and illustrated it at his website (go here).

How not to read sonar. This brings us to a key issue in this saga. The whole reason for using sonar and a camera-strobe system at adjacent, closely spaced locations in the loch, simultaneously, was that both would be (a) fixed and (b) monitoring the same expanse of water at the same time. The Raytheon sonar detector that was being used was designed to be directed downwards, but AAS had it rigged to point sideways, and the same was meant to be true for the camera-strobe system. As shown in this diagram used by Roy Mackal, the idea was that an overlapping, fixed ‘sonar cone’ and fixed ‘strobe camera cone’ would record data from any approaching Nessies.

Caption: this diagram - from Mackal (1976) - shows how a fixed sonar beam, combined with a fixed camera-strobe system, could simultaneously detect and record the nearby presence of a large animal. The diagrams of this system, deployed in the loch in 1972 (and in later years too), always show the devices as being fixed on the loch floor. Image: Mackal (1976).

Alas, the data from the sonar detector shows that both it and the camera were very much mobile, subject to wind and currents, and rocking around in the water. This is demonstrated by technical details of the sonar chart: specifically, the side-lobe trace isn’t parallel to the transducer trace. And we know this was true anyway because Dick Raynor – who was on the Narwhal throughout the relevant time period – confirms that it was. Witchell quoted Narwhal’s skipper Peter Davies, who described the appearance of the sonar trace at around 1.45am, the fact that he rowed over to Nan to tell Rines and the others what was going on, then rowed back to Narwhal with Rines and others, just before a breeze “got up and Narwhal started to swing around” (Witchell 1974, p. 131). If the camera was mobile (as it was), sufficient movement could cause it to tilt down and occasionally photograph the nearby loch floor.

Caption: there isn’t a standard nomenclature for the two photos, but I’ve taken to calling them 1 and 2, because I’m original like that. This is flipper photo 2. You can recognise it by the prominent asymmetry of its vanes, the white spot on the presumed posterior vane, and the reduced scattering of silt at the ‘flipper base’.

Here’s where we come back to the sonar readings. Recall earlier how the various readings (the squiggles, wiggles and thick wavy lines drawn by the styluses) were thought to be evidence of big animals, travelling through the area at the same time as the flipper photos were taken? Well…. nope! The annotations on the 1972 sonar chart show that the AAS/LNIB team interpreted the marks as showing the size and shape of objects presumed to be animals. But the vertical axis on the chart marks time, not distance. Those long, thick lines show that whatever was being picked up was being picked up for a given stretch of time, it does not mean that a big object (least of all a moving one in the water column) was being detected.

Given that we know that the camera and sonar devices were both mobile, the sonar device should absolutely have detected echoes from the camera, both Narwhal and Nan, their mooring chains, and their attached buoys (it’s pronounced BOYS, USA). And it’s probably these which the sonar was detecting, combined with wakes and waves on the surface (the parallel line effect present on part of the sonar sheet looks exactly like that caused by waves, boat wakes especially; Harmsworth 2010).

Caption: wakes and waves are an omnipresent feature of the loch’s surface. Here are some I’ve photographed at Loch Ness at various times (albeit in the daytime). Image: Darren Naish.

You may remember from earlier in this article the mention of a third photo in addition to the two flipper photos. This photo was taken “a few minutes later” (to quote Witchell) and said to show “two separate, hazy images” (Witchell 1989, p. 144). The official take is that these two images couldn’t be identified, but the suspicion (and implication) was that this photo depicted two monsters swimming in tandem, an observation corresponding (supposedly) to what look like two contacts on the sonar trace. But, as you can see from the photo itself, it’s more nonsense. There’s no reason at all to think that animals are involved, there’s no way of linking this image with the sonar trace (since we don’t know when during the night the photo was taken), and – as we’ve just seen – there’s no reason to think that the sonar trace shows animals.

Caption: the third photo taken on the night of 7th/8th August 1972… implied to show two animals. Excuse me if I’m a little sceptical. Image: AAS.

This was not a hoax. The history of Loch Ness Monster imagery involves a vast quantity of wishful thinking and over-keen desperation, much of it driven by people who already believe in the monster, and want others to be convinced by the evidence too, such as it is. And that’s what happened here. The whole ‘Nessie Flipper’ saga is often described or characterised as ‘a hoax’. But that’s not really what it was. For starters, the key players here – those in the LNIB and AAS – honestly believed that Nessie was real (which is a faulty and naïve starting point, but we all make mistakes). When they got those sonar and photographic records in August 1972, I believe that they honestly thought they’d gathered valuable and compelling evidence. Add in some ‘eye of faith’, a fair bit of desperation that surely some good must come of all this time, equipment, money and people-power, and those concerned managed to convince themselves that they’d succeeded in recording images of flippers in the two relevant photos. Photographic enhancement seemed to boost this conclusion, but the visuals still weren’t impressive enough for those already critical or dismissive of the Loch Ness Monster, so the best course of action (as determined by an unknown perpetrator or perpetrators) was to enhance the ‘flippers’ physically, on the printed photos. Again, I don’t think this was done maliciously or to fool anyone but, rather, to convince them, the thinking being “now YOU can see the flippers too, right?”.

The confidence that Rines and his colleagues had in the reality of the flippers is in part demonstrated by the fact that, in 1979, they had students at MIT construct a life-sized model of one of the flippers for Tony Harmsworth’s Loch Ness exhibition. As recounted in his book, Harmsworth collected this in person, hand-carrying it via taxis and so on after picking it up in Boston… but it became lost during transit, since he had to swap planes several times due to severe storm conditions over Europe (Harmsworth 2010). The model flipper – more than 2 metres long and green – is still of unknown whereabouts and it would be fantastic to know what happened to it.

Caption: I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again… you need to read books to get this information.

The paradigm shift sought by the LNIB and AAS – that Nessiteras is real, and that evidence for this contention had been obtained in 1972 (and in 75, when more underwater photos were claimed) – never happened, because belief in the monster waned, the key players died, gave up, or became sceptical, and the evidence, such as it was, was never at all convincing to those with doubts.

Nevertheless, I often imagine how exciting it must have been to be involved in this saga during the early 70s, to believe that proof really had been obtained, and I wonder what it was like to be on either of those boats, surrounded by the blackness of the loch and the night, and to think that an immense aquatic animal, 10 metres long or more, was swimming some short distance below…. if only it were so. But it wasn’t.

For previous TetZoo articles on the Loch Ness Monster, lake monsters, and cryptozoology more generally see…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent, November 2019

Refs - -

Anon. 1976. “Nessie”: what’s in an anagram? Science 191, 54.

Bauer, H. H. 2002. The case of the Loch Ness “monster”: the scientific evidence. Journal of Scientific Exploration 16, 225-246.

Baynham-Herd, Z. 2020. Presenting endangerment: Peter Scott, conservation, and the Loch Ness Phenomena. Environmental Humanities 12: 1, 370-387.

Corbet, G. B. 1976. The Loch Ness Monster. Nature 259, 75.

Dinsdale, T. 1973. The Rines/Egerton picture. The Photographic Journal April 1973, 162-165.

Dinsdale, T. 1976. Loch Ness Monster, Revised Edition. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Halstead, L. B., Goriup, P. D. & Middleton, J. A. 1976. The Loch Ness Monster. Nature 259, 75-76.

Harmsworth, T. 2010. Loch Ness, Nessie and Me: the Truth Revealed. A. G. Harmsworth, Drumnadrochit.

Mackal, R. P. 1976. The Monsters of Loch Ness. The Swallow Press, Chicago.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Rines, R. H., Edgerton, H. E., Wyckoff, C. W. & Klein, M. 1976. Search for the Loch Ness Monster. Technology Review March/April 1976, 25-40.

Scott, P. 1976a. Why I believe in the Loch Ness Monster. Wildlife 18, 110-111.

Scott, P. 1976b. The Loch Ness Monster. Nature 259, 75.

Scott, P. 1976c. The Loch Ness Monster. Nature 259, 76.

Scott, P. 1980. Observations of Wildlife. Phaidon Press, Oxford.

Scott, P. 1987. Travel Diaries of a Naturalist III. Collins, London.

Scott, P. & Rines, R. 1975. Naming the Loch Ness monster. Nature 258, 466-468.

Shine, A. 1984. A very strange fish? In Brookesmith, P. (ed) Creatures From Elsewhere.. Macdonald & Co, London, pp. 66-70.

Taylor, M. A. & Martin, J. G. 1990. Big Mouths and Long Necks: the Plesiosaurs. Leicestershire Museums, Leicester.

Williams, G. 2015. A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Books, London.

Witchell, N. 1974. The Loch Ness Story. Penguins Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

Witchell, N. 1989. The Loch Ness Story (Revised and Updated Edition). Corgi Books, London.