You’re already highly familiar with the Dodo Raphus cucullatus, and images of what this animal looked like in life are present in a vast number of books, popular sources and museum displays. What might not be so familiar to you is that the Dodo’s life appearance has been the subject of long-standing debate, that many familiar ideas about its appearance are very likely wrong, and that – even today – we’re uncertain about several details.

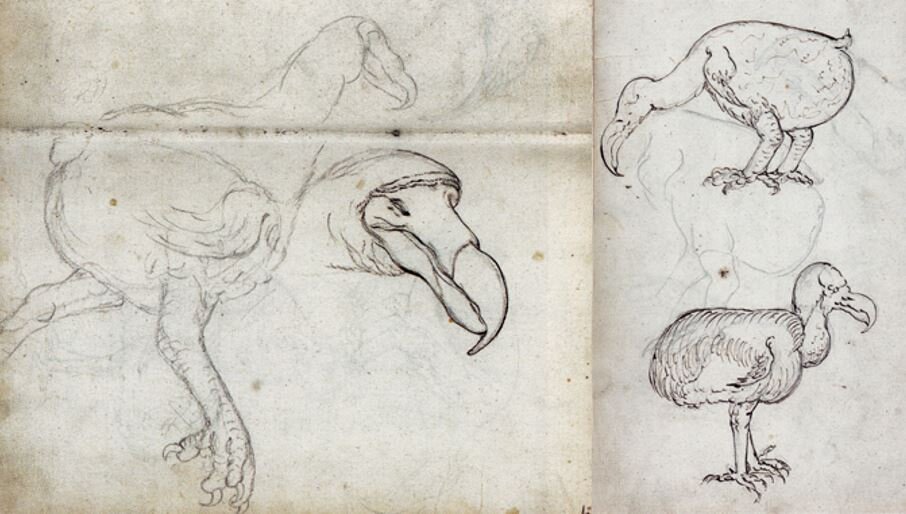

Caption: among the most important of Dodo images are these from the Gelderland journal of 1601. These were first published by Kitchener (1993a) and have more recently been discussed by Hume (2003) and Parish (2013). Images: public domain.

The Dodo – endemic to Mauritius, made extinct at some unknown point in the late 1600s (Roberts & Solow 2003, Hume et al. 2004, Cheke 2006) – was a giant, flightless pigeon, closely related to Nicobar pigeons (Caloenas) and crowned pigeons (Goura). This affinity is demonstrated by numerous anatomical details (Fjeldså 1976, Janoo 1996, 2000, Livezey & Zusi 2007, Parish 2013) and also by genetics (Shapiro et al. 2002, Pereira et al. 2007). Just knowing about the Dodo’s affinities is useful, since there are a few aspects of Dodo anatomy where we can look to its extant relatives for guidance. Example: obvious sexual dimorphism in plumage (at least, visible to the human eye) is not present in those close living relatives.

Caption: two of the Dodo’s closest living relatives are the extravagantly plumed Nicobar pigeons (Caloenas) and the crowned pigeons (Goura). Images: Darren Naish.

The source materials. First things first. There exist a substantial number of historic Dodo images which depict innumerable details of the Dodo’s plumage, colouration, bill shape and so on. And there also exist some number of books and published articles where workers have described these and interpreted them as casting light on the animal’s appearance in life.

Caption: probably the most famous depiction of the Dodo ever created, the ‘Edwards’ Roelandt Savery painting. It shows a great many features that have become entrenched in images of the bird including prominent bill ridges, a big, shaggy wing, a curly tail and short legs. The painting is large and shows the bird as larger than life size: it’s about 80 cm tall with a head 30 cm long. Image: public domain.

By far the most famous and influential of these are the paintings attributed to Roelandt Savery, in particular the giant 1626 painting which once belonged to writer and artist George Edwards. Supposedly based on a live bird kept in Holland, it’s today at the Natural History Museum, London (Fuller 2002, Parish 2013). Incidentally, we’re not completely sure that Savery really was the creator of this painting but I will – from hereon – assume that he was for the sake of convenience. A second very famous Savery Dodo painting – this time by Roelandt’s nephew, Jan or Hans Savery – is on show at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and might have been produced in 1631. Regardless, all of these ‘Savery’ Dodo paintings show grey (though read on), chunky, exceedingly bulky, short-legged birds with yellowish wing and tail plumes.

Despite claims that R. Savery’s 1626 painting was produced from life, it doesn’t match other images which more certainly were and it seems likely that it was based on taxiderm specimens or written accounts. For these reasons it (and other ‘Savery Dodos’) can’t and shouldn’t be taken as providing especially important insights into Dodo appearance or anatomy.

Caption: the right side of the Oxford Dodo head, the most significant remaining piece of soft tissue evidence pertaining to the bird. There’s a lot that could be said on it. Note that much of the rhamphotheca is missing. Image: gnomonic, CC SA 2.0 (original here).

This is all a long-winded way of saying that we have to rely on other sources as best we can. What are these sources? They include data on proportions and mass which we can glean from good skeletons (Kitchener 1993a, Livezey 1993), some surviving bits of preserved soft tissue evidence (essentially, what remains of the Oxford Dodo, namely the famous head and foot which originally belonged to the Tradescant collection*) and several illustrations done from live specimens.

* A second foot (a right foot) was previously present in the collections of the British Museum but is today of unknown whereabouts. It seems to have gone missing during the early decades of the 20th century. Good illustrations and surviving casts mean that we at least know what it looked like.

Caption: this image, from Het Tvveede Boeck of 1601, shows what appears to be a lean, walking Dodo at upper left. The image appears in Kitchener (1990), Fuller (2002) and other sources. Image: public domain.

The most famous of these illustrations done from life are those from the Gelderland Journal, produced by at least two anonymous artists who were onboard the vessels of a Dutch fleet which anchored off Mauritius in 1601 (Hume 2003). The drawings depict both a dead or stunned Dodo laid out on a table as well as one or more live Dodos in standing pose (Kitchener 1993a, Hume 2003, Parish 2013). Another Dodo drawing from the early days of Mauritian discovery and exploration is that featured in the Dutch volume Het Tvveede Boeck of 1601. This reported a 1598 expedition led by Admiral Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck (Fuller 2002, Hume 2006, Parish 2013) and hence the Dodo featured therein has often been called the Van Neck Dodo. A very influential illustration and account produced by the French naturalist Carolus Clusius in 1605 – it will be referred to a few times in this article – was apparently copied from a drawing in Van Neck’s journal, but the original has been lost.

Caption: at left, Carolus Clusius’s Dodo of 1605, shown with what’s said to be a gizzard stone. At right, Jacob Höfnagel’s Dodo illustration of 1602. This was almost certainly based on a taxiderm specimen. Images: public domain.

There’s also the colour watercolour produced by Jacob Höfnagel in or around 1602, the unusual posture, withered head and distorted feathering of which means that it’s been interpreted as showing a “badly-mounted preserved specimen” (Kitchener 1993a, p. 280; see also Fuller 2002, Hume 2006). An interesting colour painting produced by Cornelis Saftleven in around 1638 has an air of realism which forces writers like myself to pay attention to it (this might be a trick and it could be worthless), and it also gets mention here. Saftleven’s painting is also unusual in showing the bird in three-quarters view. It’s of unknown provenance and we don’t know if it was based on a live bird.

Caption: at left, the Cornelis Saftleven portrait. It may or may not be an important portrait of the species. At right, Ustad Mansur’s painting. This was stolen from India and taken to Persia in the 1700s, and brought to international attention by Aleksander Ivanov after he noticed it in an exhibition of Indian and Persian art at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 1955. Images: public domain.

Finally, we come to the technically impressive Ustad Mansur painting of 1625. Mansur illustrated animals for Emperor Jahangir of the Mughul Empire who kept a menagerie at Surat, India; Jahangir’s scientific curiosity led him to order the creation of technically rigorous works which were meant to be as accurate and detailed as possible (Dissanayake 2004). As we’ll see, Mansur’s Dodo is one of the most significant depictions of the species in life. And, yes, it seemingly means that at least one live Dodo was present in an Indian menagerie during the 1620s.

The Dodos of Van Neck, Clusius and Savery are essentially the ‘originals’ from which virtually all later Dodos were copied, and both Kitchener (1993a) and Parish (2013) produced genealogies showing how subsequent artists based their Dodos on those of these artists. Mansur’s Dodo was not treated in the same way since it was essentially unknown until Ivanov (1958) brought attention to its existence.

Caption: the Dodo model at the National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh, created under the direction of Andrew Kitchener and discussed in Kitchener (1990, 1993a, b). Image: Darren Naish.

There’s one more thing to say on sources, and that’s that there are a few especially useful modern works very relevant to the subject of this article. I can still remember the excitement caused by Andrew Kitchener’s several articles of the 1990s in which Kitchener (who’d been tasked with the creation of a new reconstruction for the National Museums of Scotland) explained his use of historical sources and the cantilever strengths of Dodo limb bones in the construction of a new life-size model, shown here (Kitchener 1990, 1993a, b). Errol Fuller’s books on the Dodo and extinct birds in general (Fuller 2000, 2002) and Julian Hume’s several articles on the Dodo and other Mauritian birds (Hume 2003, 2006, Hume & Cheke 2004, Hume et al. 2006) are also essential sources.

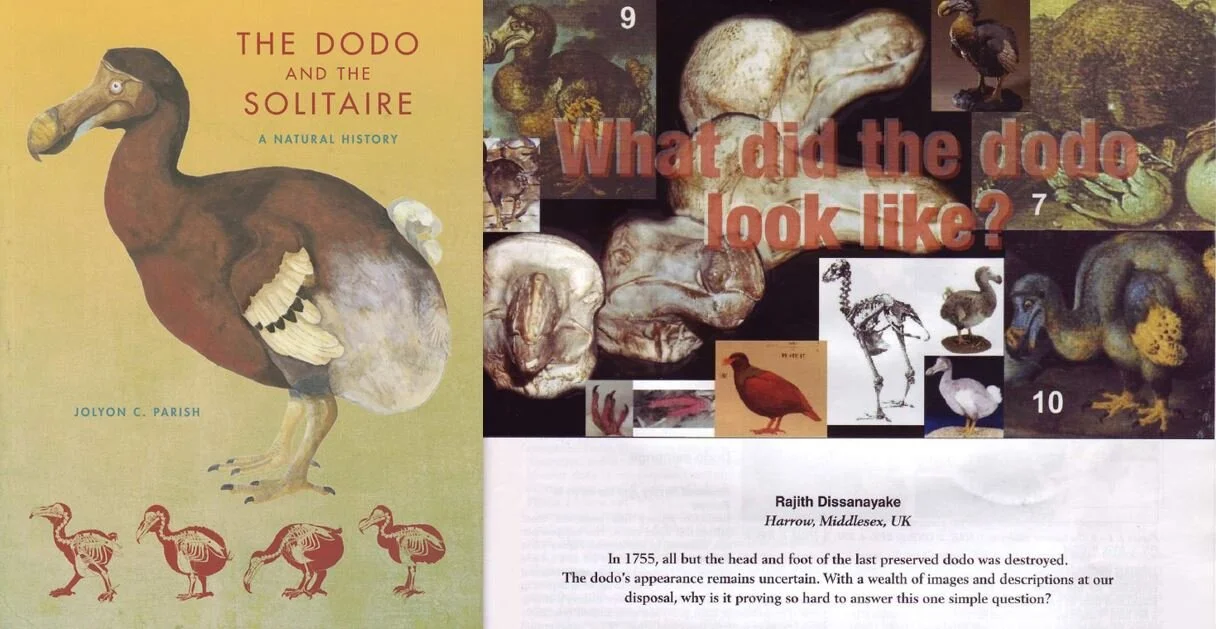

More recently, Jolyon Parish has produced an excellent and highly comprehensive volume on all things Dodo, namely the 2013 book The Dodo and the Solitaire: a Natural History (Parish 2013) (I reviewed it for Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: you can read my review here). Finally, a very useful article by Rajith Dissanayake, titled ‘What did the Dodo look like?’, was published in 2004 (Dissanayake 2004) and I used it in compiling the article you’re reading now.

Caption: at left, Jo Parish’s 2013 volume, a must-have for those interested in extinct birds. At right, part of the cover page of Rajith Dissanayake’s Biologist article on Dodo life appearance.

Enough preamble. What do we know? First of all, existing skeletal remains show that the Dodo was large. Authors of the 1600s mostly compared the Dodo to turkeys or swans, which might have helped contribute to ideas that it was heavier and taller than it was. A standing height of 62-65 cm seems average (Parish 2013); I haven’t seen any length estimates but 70 cm or thereabouts should be considered about right for an average specimen. By scaling up the volume of an accurate model, estimating total mass based on that of the skeleton and using scaling relationships established for limb bones and eggs, Kitchener (1993a) calculated body masses of between 10.6 and 17.5 kg, and more recent studies which incorporate higher numbers of specimens have suggested 12 kg as typical (Angst et al. 2017, van Heteren et al. 2017); 8-10.8 kg has been suggested based on a convex hulling technique that cannot account for the mass of internal organs (Brassey et al. 2016).

Posture, fat, the crop, and the belly. Both illustrations and written accounts made from observations of live birds (Hume 2003, Parish 2013), and work on the bending stress of the femur (Kitchener 1993a, b), show that the Dodo had a relatively erect posture, and its femur may have been held in a more erect pose than ‘classically’ imagined. Illustrations which show the bird as massively overweight and with its chest or belly only just above the ground are not, therefore, accurate.

Caption: Kitchener’s work of the early 1990s got a fair amount of coverage, part of its appeal being that it designed a new, slimline look for the Dodo. Also worth noting is that good new publications on Dodo osteology have appeared in recent years, like the Claessens et al. monograph.

The idea that Dodos had seasonal fat and thin cycles has been suggested on many occasions, and it could be that a fat Dodo was noticeably larger in parts of the body than a trim one. However, even the fattest Dodo would not have been as rotund as is shown in some classic paintings, and what seems more likely (based on the biology of other birds) is that fat was stored in specific parts of the body, and not on the belly or around the chest. The rotund, heavy look to that part of the body posterior to the legs – it’s very prominent in Mansur’s painting – makes it look as if this was a fat store, and I would predict that this is the area where we’d see seasonal fluctuations in size (as we do in, for example, migratory swans).

A few authors have suggested that the slightly convex basal section of the neck in Mansur’s painting and some of the Gelderland drawings corresponds to a crop, a structure which the Dodo almost certainly had in view of its columbiform identity. In fact, the Dodo likely had an especially big, bilobed crop, like other pigeons. I personally don’t think that we’re seeing anything exceptional in any of these images, but it remains possible that a Dodo with a stuffed crop could have looked bulky at the neck’s base.

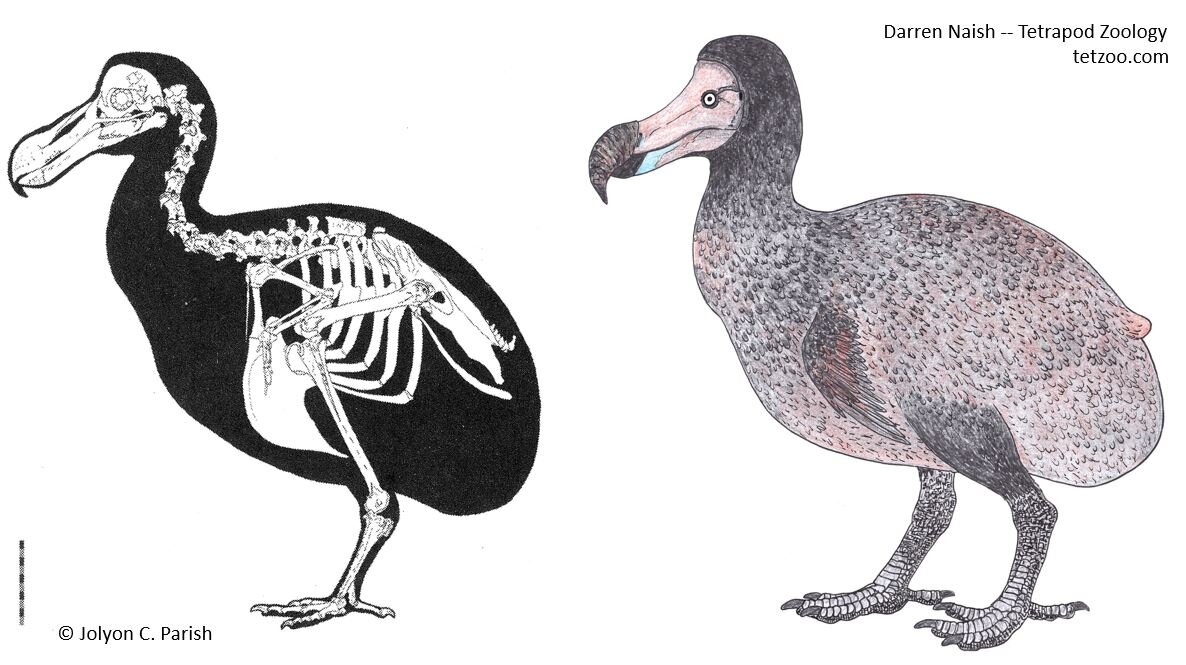

Caption: Parish’s 2013 skeletal reconstruction, at left, closely matches the profile and proportions of the Mansur painting. My own life reconstruction, at right, was made with reference to the Mansur painting in particular. Images: (c) J. Parish; Darren Naish.

Note that the Gelderland drawings, and the Höfnagel and Mansur paintings all show Dodos as tall animals where the lower edge of the belly is level with – or higher than – the ankle joint. This is depicted so consistently that it must be considered correct, and it also means that there’s no good reason to think that even a fat Dodo put on so much weight that its belly extended below its ankles.

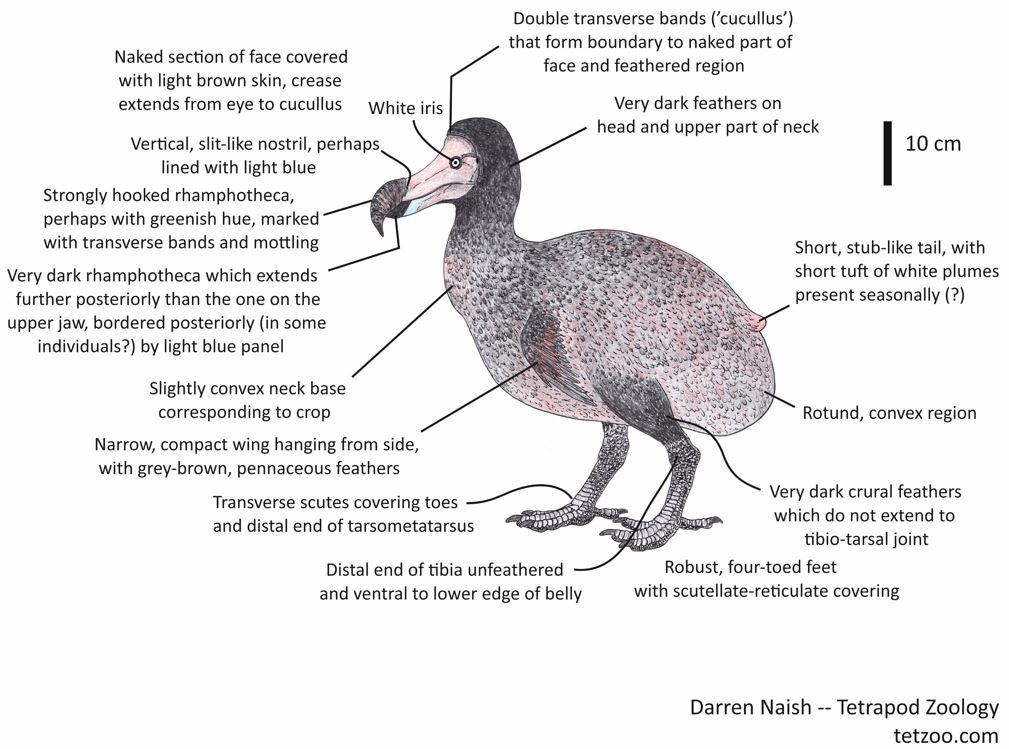

The bill. Moving now to the head, the rhamphotheca on the upper jaw (the ‘beak tissue’) is said to have been light green, perhaps with a yellowish tint (Dissanayake 2004, Parish 2013). Illustrations like the Saftleven portrait indicate that the rhamphotheca was marked with dark bands and mottling, and there’s also reference here and there to a series of ridges at the rear edge of the beak’s dorsal surface. While there’s been some substantial speculation on how these ridges might have varied due to age or sex, they’re not depicted in the more reliable of those images depicting Dodos in life. I agree with Parish (2013, p. 276) that the ridges “are almost certainly due to the drying out of a preserved specimen” and weren’t present in life.

Caption: another life-sized Dodo model, this time one on show at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Like the models at the Natural History Museum, it’s likely heavily inspired by the Savery paintings. Note that the transverse dorsal ridges close to the border of the upper rhamphotheca have been faithfully portrayed. They probably weren’t present in life. Images: Darren Naish.

The rhamphotheca at the tip of the lower jaw* is shown as very dark in the Mansur painting and bordered by a pale triangle of skin which has a blueish hue (read on). Most other works are ambiguous on the appearance of this part, though some of Savery’s paintings and the Saftleven image also show the lower jaw tip as dark. There’s no reason to depict the lower jaw’s rhamphotheca as yellowish.

* Ornithological terminology for the upper and lower parts of the bill is confusing and odd. You’re supposed to call the upper part of the bill the maxilla and the lower part the mandible, which is problematic because the same terms are used for major parts of the skull.

Caption: the face of the Dodo model at National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh. This model is very good, but there are some details that might be off. The lower jaw’s rhamphotheca should likely be black, the nostril should be slit-like rather than wide open, and the animal overall should perhaps be brown rather than grey. Image: Darren Naish.

The rest of the face. The nostrils appear to have been vertical and located posteroventral to (behind and on the lower side of) the beak, as is typical for pigeons; in shape it looks like they were similar to those of crowned pigeons. They’re often shown as open and oval, but Hume (2006) noted that they were likely slit-shaped in life and that the open condition shown in some art is based on the Oxford head and is thus an artifact of desiccation.

The face was bare, but accounts differ on its colour. Mansur’s painting makes it look as if the face was light brown or greyish, perhaps darkest around the mouthline and eyes, and Höfnagel’s painting shows a dark face similar in hue to the rest of the head and neck (though keep in mind that it almost certainly shows a taxiderm specimen). Parish (2013) considered it possible that the descriptions of the face as whitish, grey, grey-greenish or brown were all plausible. Perhaps the colour of the facial skin varied in accordance with the plumage (on which… read on)

Caption: the most influential image of the Dodo’s face - alongside the Savery paintings - is that published by Hugh Edwin Strickland and Alexander Melville in their 1848 The Dodo and Its Kindred. Several of the details here are surely correct but a few small details might be missing, like the skin crease connecting the eye to the cucullus and the slit-like form of the nostril. Image: in public domain.

The posterior margin of the naked part of the face is marked by a dark transverse band, termed the cucullus (Parish 2013). Some of the Gelderland drawings show that the cucullus was formed of two parallel bands (Hume 2003). There also seems to have been a horizontal skin fold extending from the posterior corner of the eye to the transverse band (Hume 2003, Parish 2013). The eye is shown by Mansur as having an entirely white iris.

That part of the lower jaw posteroventral to the rhamphotheca is especially interesting, since this was definitely much paler than the naked skin elsewhere on the face (in some individuals, that is), was shown as blue by Mansur and was stated to be blue by Clusius. Even better, SEM analysis of the skin of the Oxford Dodo head has confirmed a blueish tint to the skin here, this apparently being a structural colour caused by Tyndall scattering (Parker 2005, cited in Parish 2013). Maybe this was a display feature which was only blue in the members of one sex, or only at certain times of the year. Also worth noting is that Mansur depicted a blue vertical stripe close to the posterior border of the upper jaw’s rhamphotheca: it looks like it was present at one or both margins of the nostril.

Caption: some of the features depicted by Mansur (including a brownish face and blue jaw panel) haven’t been shown all that often elsewhere. Images: public domain; Darren Naish.

The plumage. What colour was the rest of the Dodo? This question has a more complex answer than you might imagine. The general impression we get from imagery depicting the Dodo, and from most texts on it, is that it was grey, or blue-grey. This is most famously emphasised by the Savery paintings, but we’ve already seen that these perhaps aren’t all that reliable. In fact, authors who wrote about Dodos in life said that they were everything from whitish to brown and near-black (e.g., Hachisuka 1953). As an island-dwelling animal with a small gene pool and no obvious predation, it’s possible that the Dodo was highly variable in colour, and that albinistic and melanistic mutants weren’t ‘weeded out’ by selection pressures. A Savery painting from 1611 has been interpreted by some authors as showing a truly white Dodo which was perhaps an albino (Hume & Cheke 2004, Hume 2006).

Caption: life-sized Dodo model constructed for the Natural History Museum’s Extinction: Not the End of the World exhibition of 2013. I don’t know anything about it but it appears to be based on the model in Edinburgh. In some details (like the wide open nostrils) it’s very similar, but its browner plumage, darker, mottled rhamphotheca and lack of fluffy tail plumes make it different. Images: Darren Naish.

With that in mind, Mansur’s image seems to be the most reliable guide to colour in life, not only because of the circumstances surrounding its creation but also because the other birds depicted in the work (a Western tragopan Tragopan melanocephalus, Painted sandgrouse Pterocles indicus and Blue-crowned hanging parrot Loriculus galgulus) are accurate relative to their real-world counterparts*. And Mansur showed the bird as brown with a blackish head and neck, and with blue-grey patches on the sides of the body (Dissanayake 2004).

* There are also two ducks of some sort in the Mansur painting, and unfortunately they’re not accurate. The most popular suggestion – following Stresemann’s (1958) identification – is that they’re meant to be juvenile Bar-headed geese Anser indicus but they sure don’t look like it. They do present a problem for the claim that Mansur’s painting is scrupulously accurate, and they might be fictional, decorative or faithfully copied from another source.

Caption: close-up of Mansur’s Dodo. A brown overall colour is evidence, as is a very dark head and neck, a slender, compact wing and the lack of a feathery tail. Image: public domain.

While some authors have referred to the Dodo’s plumage as ‘downy’ (e.g., Livezey 1993), this isn’t accurate. The feathers were pennaceous, and not of the degraded sort that give some flightless birds a shaggy plumage. The feathers on the Oxford Dodo head are arranged in groups of three – which is unique (Parish 2013) – and are stiff and black-brown.

The wing. The wing was obvious in life and hung in limp fashion to partially overlap the top of the tibia. Based on the Gelderland drawings, the wing was slim and pointed, and the tips of at least a few primaries (accounts and artwork indicate a minimum of 3 or 4 and a high of 7 or 8) were visible along the trailing edge. Coverts were likely obvious too and somewhat differentiated from the primaries but this isn’t obvious from existing sources. The primaries (and presumably the other wing feathers too) weren’t loose-vaned like those of ratites, but with symmetrical, ‘tidy’ vanes (Parish 2013).

The main point is that the wing was very different from the bulkier, luxuriantly feathered, messier organ depicted in the Savery paintings and those depictions which copied them. It’s been claimed that a small alula is visible in one of the Gelderland illustrations (Dissanayake 2004) but I’m not convinced. Views on the colour of the wings vary from one source to the next: white, yellowish, pale grey, brown and black have all been stated, and may again relate to variation within the species. Mansur’s painting indicates that the coverts exhibited varying shades of brown while the primaries were paler, and brownish white.

Caption: an assortment of Dodo literature kept at TetZoo Towers. It’s thanks to Julian Hume that I own some of this. Image: Darren Naish.

The tail. A perplexing and controversial aspect of Dodo appearance concerns its tail. Most famous illustrations – most notably the Savery paintings – depict a mass of off-white, fluffy feathers (looking a bit like super-curly, degraded ostrich plumes) located high on the rump, if not virtually on the top of the hips. It’s a classic feature of the bird’s life appearance.

Caption: these models - both on show at the Natural History Museum in London - again depict the ‘classic’ take on the Dodo. The wings are shown as large and bulky, the tail is formed of curling, bushy feathers, the face is bulky and not markedly long or narrow, and the legs look short. These models are probably assumed by some or many visitors to be stuffed Dodos, rather than the models they are. Images: Darren Naish.

But this unusual feature (which doesn’t much recall any structure seen in other pigeons) isn’t consistently depicted in those illustrations done from life. The Het Tvveede Boeck, Höfnagel, van de Brij and Clusius depicted small, short, tuft-like tails while the drawings in the Gelderland journal don’t show one, at best featuring a short, blunt, stub-like tail (Hume 2003). The possibility that plumes were only present seasonally and disappeared and reappeared with the moult has been suggested (UPDATE: see Angst et al. 2017 for some discussion of this; the relevant sections are quoted in the comments below), and some authors have also referred to a series of bristle- or tuft-like feathers ventral to the cloaca (e.g., Hachisuka 1953). Ultimately, we don’t have enough data here to be confident either way on what the life condition was. My conclusion – based on what was depicted in those illustrations of the early 1600s and by Mansur – is that a small, short tuft of pale feathers was present seasonally, and that a blunt stump was present at other times.

Caption: this montage from Kitchener (1993a) gives a good idea of how the Dodo’s tail was depicted by those who saw the bird first hand. We’re seeing (a) Het Tvveede Boeck Dodo; (b) Jacob Höfnagel’s painting; (c) the van der Brij illustration (essentially another version of Het Tvveede Boeck Dodo); (d) one of the Gelderland drawings, and (e) Carolus Clusius’s Dodo. Clearly, the tail was either small, near-absent or absent. Image: Kitchener (1993a).

The legs and feet. Finally, the legs were obvious, and long, robust and powerful. Everything from the ankle joint downwards was visible beneath the body and unfeathered; in fact, the Gelderland drawings and the paintings by Höfnagel and Mansur show the distal end of the tibia as naked; that is, with the crural feathers not extending to the tibio-tarsal joint. In this detail, the Dodo appears to have differed from crowned and Nicobar pigeons. The mostly feathered, proximal portion of the tibia appears to have been visible, the leading edge of this part of the limb being visible beneath the wing. Mansur’s image shows the crural feathers as dark, and Clusius described how the feathers “to the knee” (meaning ankle) were black. All of this stands in marked contrast to classic illustrations (like Savery’s) where the legs are short and mostly feathered except for the feet.

Caption: Dodos drawn from life - like those shown in the Gelderland journal - show relatively straight legs, prominently displayed beneath the body. Both the Gelderland drawings and Mansur’s painting (shown at far right) show that the leg was unfeathered from the distal part of the tibia downwards. Images: public domain.

Thanks to the images and casts of the (lost) London foot, we have good information on the distribution and patterning of the podothecae (the ‘scales’ on the toes and rest of the foot). The pattern of scalation was scutellate-reticulate (not reticulate as stated by Parish 2013), which means that there were large, transverse scutes on parts of the limb (in this case, on the toes and the distal part of the tarsometatarsus), and small, irregularly shaped scutes elsewhere. As expected for a large groundbird, the foot’s underside was covered in a huge number of tiny, rounded scutes, and fleshy pads were present on the undersides of the toes.

Caption: thanks to the British Museum Dodo foot - the original of which is lost - we have good data on the look of this part of the body. These images (attributed to Joseph Dinkel) originally appeared in G. E. Gray’s 1849 The Genera of Birds. Image: public domain.

When it comes to colour, there’s mention in a catalogue of the 1680s of the foot being covered with “reddish yellow” scales, and Clusius said that the feet were yellowish. The Mansur image has usually been interpreted as showing the feet as too pale (Dissanayake 2004) and there are indeed reasons for thinking that some colours in the image have faded (Parish 2013, p. 74): the feet of the lorikeet in the painting are greyish, whereas those of live specimens are orange or pinkish. The Dodo’s claws in the painting are shown as dark grey or near black.

And that just about sums up everything we know. As per my other articles on the life appearance of recently extinct animals (see below for links), I’ve summarised all of the information discussed here in the ‘cheat sheet’ you see here, and I hope it proves useful for those who wish to illustrate Dodos themselves. I should add that I absolutely am not claiming to be the first to pull all of this stuff together or reconstruct the Dodo in this way: it’s been done by others beforehand. Have a look in particular at the Wildlife Preservations Dodo, made for display at the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research in Singapore, currently (as of July 2020) on show at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum at the National University of Singapore.

I’m not sure whether it’s surprising or unsurprising that we have so little to go on for an animal that died out just 400-ish years ago, but the fact remains that relatively few people properly and accurately recorded the appearance of this animal while it was alive. As several authors have said, the ‘window’ during which people got to know of the existence of the Dodo before it was gone forever was extremely short, so short that some European authors in the 1700s and 1800s even doubted that such a remarkable bird ever existed.

For previous articles on the life appearance of recently extinct animals seen by people - and on pigeons - see…

The remarkable life appearance of the Woolly rhino, November 2013

Spots, Stripes and Spreading Hooves in the Horses of the Ice Age, February 2015

Pigeons and Doves 101, March 2018

The Life Appearance of the Giant Deer Megaloceros, September 2018

Refs - -

Cheke, A. S. 2006. Establishing extinction dates – the curious case of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the Red hen Aphanapteryx bonasia. Ibis 148, 155-158.

Dissanayake, R. 2004. What did the dodo look like? Biologist 51 (3), 165-168.

Fjeldså, J. 1976. The systematic affinities of sandgrouses, Pteroclidae. Videnskabelige Meddeleser fra Dansk Naturhistorisk Forening 139, 179-243.

Fuller, E. 2000. Extinct Birds. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Fuller, E. 2002. Dodo: From Extinction to Icon. Collins, London.

Hume, J. P. 2003. The journal of the flagship Gelderland – dodo and other birds on Mauritius 1601. Archives of Natural History 30, 13-27.

Hume, J. P. 2006. The history of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and the penguin of Mauritius. Historical Biology 18, 65-89.

Hume, J., Martill, D. M. & Dewdney, C. 2004. Dutch diaries and the demise of the dodo. Nature doi: 10.1038.

Hume, J. P. & Cheke, A. S. 2004. The white dodo of Réunion Island: unravelling a scientific and historical myth. Archives of Natural History 31, 57-79.

Hume, J., Datta, A. & Martill, D. M. 2006. Unpublished drawings of the Dodo Raphus cucullatus and notes on dodo skin relics. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists’ Club 126, 49-54.

Ivanov, I. 1958. An Indian picture of the Dodo. Journal of Ornithology 99, 438-440.

Janoo, A. 1996. On a hitherto undescribed dodo cranium, Raphus cucullatus L. (Aves, Columbiformes), with a brief taxonomical overview of this extinct flightless Mascarene Island bird. Bulletin du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris 4e série, 18, Section C, no 1, 57-77.

Janoo, A. 2000. Rooting the dodo Raphus cucullatus Linnaeus 1758 and the solitaire Pezophaps solitaria Gmelin 1789 within the Ornithurae: a cladistic reappraisal. Ostrich 71, 323-329.

Kitchener, A. C. 1990. Expedition to wonderland. BBC Wildlife 8 (8), 512-514.

Kitchener, A. C. 1993a. On the external appearance of the dodo, Raphus cucullatus (L., 1758). Archives of Natural History 20, 279-301.

Kitchener, A. C. 1993b. Justice at last for the dodo. New Scientist 139 (1888), 24-27.

Livezey, B. C. 1993. An ecomorphological review of the dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), flightless Columbiformes of the Mascarene Islands. Journal of Zoology 230, 247-292.

Livezey, B. C. & Zusi, R. L. 2007. Higher-order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy. II. Analysis and discussion. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149, 1-95.

Parker, A. R. 2005. A geological history of reflecting optics. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 2, 1-17.

Pereira, S. L., Johnson, K. P., Clayton, D. H. & Baker, A. J. 2007. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences support a Cretaceous origin of Columbiformes and a dispersal-driven radiation in the Paleogene. Systematic Biology 56, 656-672.

Roberts, D. L. & Solow, A. R. 2003. When did the dodo become extinct? Nature 426, 245.

Shapiro, B., Sibthorpe, D., Rambaut, A., Austin, J., Wragg, G. M., Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P., Lee, P. L. M. & Cooper, A. 2002. Flight of the dodo. Science 295, 1683.

Stresemann, E. 1958. Wie hat die Dronte (Raphus cucullatus L.) ausgesehen? Journal fur Ornithologie 99, 441-459.