Yes, it’s time to review another famous English zoo…

Caption: a Bristol Zoo montage. Clockwise from upper left: South American fur seal, Rhinoceros iguana, Asiatic lion, Common eider, Clown knifefish, Dwarf Indian mudskipper. Images: Darren Naish.

Enough people read, and I hope liked, my recent review of ZSL Whipsnade Zoo – part of my slow-burn TetZoo Reviews Zoo series (see bottom for links) – that it’s high time I do another. And thus, I’ve decided to publish my thoughts on Bristol Zoo… and not a moment too soon, as the zoo is set to close permanently in 2022. While this might sound disastrous to the people of Bristol and the surrounding region – Bristol Zoo is popular, much loved, and with a rich history that links it to the city – the good news is that the zoo isn’t, technically speaking, closing entirely. Rather, it’s moving to a new location, this being the Wild Place Project on the northern edge of the city, where it will officially open… should I say reopen? … in 2024.

Located in hilly Clifton in the west of Bristol, close to Clifton Down and the River Avon, Bristol Zoo (technically known as Bristol Zoo Gardens or even Bristol Zoological Gardens) is a relatively small, well planted zoo featuring numerous indoor and outdoor exhibits. It’s home to over 300 species, a significant percentage of which are endangered and not generally on show elsewhere. There is in fact so much in the zoo that I haven’t covered everything in this article, nor (despite at least three visits) have I ever spent time seeing everything there, as I’ve always ended up spending the bulk of my time in two or three of the zoo’s several sections.

Caption: zoos tend to be famous for their charismatic megafauna, but it’s not difficult for even a small zoo to have a strong and fascinating collection of smaller animals, like birds. Bristol has long been pretty good for wildfowl, and here are some highlights. At left: the global superstar that is Meller’s duck Anas melleri; upper right Marbled teal Marmaronetta angustirostris; lower right Chiloé wigeon Mareca sibilatrix. Images: Darren Naish.

Some history. Bristol Zoo is a Victorian zoo that opened in 1836, this making it the world’s oldest zoo not contained within a capital city. Some of its design and architecture reflects this history. Several of its buildings (including the entrance lodge) are listed and today regarded as inadequate or inappropriate for the animals they were built for. Consequently, they’ve been retooled.

In the UK, the zoo is famous for being the setting of the 1960s television series Animal Magic featuring Johnny Morris. The premise of the show (which I remember watching as a kid, albeit not during the 1960s as I didn’t exist then) was that Morris worked there as a keeper and could talk to, and understand, the animals… for which he provided the voices. It’s fairly cringey stuff today but kids loved it, including myself, I think.

The zoo is also well known for its breeding and conservation work, its projects including those concerning forests and their wildlife in northern Madagascar, African penguins Spheniscus demersus, Kordofan giraffe Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum in Cameroon, the Negros bleeding heart dove Gallicolumba keayi in the Philippines and much else. The zoo is also involved in the conservation of the critically endangered Livingstone’s fruit bat Pteropus livingstonii of the Comoros Islands and has a breeding group on show.

Caption: Bristol Zoo has a good group of African penguins and is involved with conservation work revolving around this species. Image: Darren Naish.

A surprising number of historic ‘firsts’ are associated with Bristol Zoo. The zoo housed the first chimp Pan troglodytes to be born in captivity in Europe (named Adam, he was born there in 1934) as well as Britain’s first captive-bred Black rhino Diceros bicornis, born there in 1958, and first captive-bred Okapi Okapia johnstoni, born there in 1967. All three of these animals are among the list kept there in the past but not there today, others including Polar bear Ursus maritimus and Asian elephant Elephas maximus.

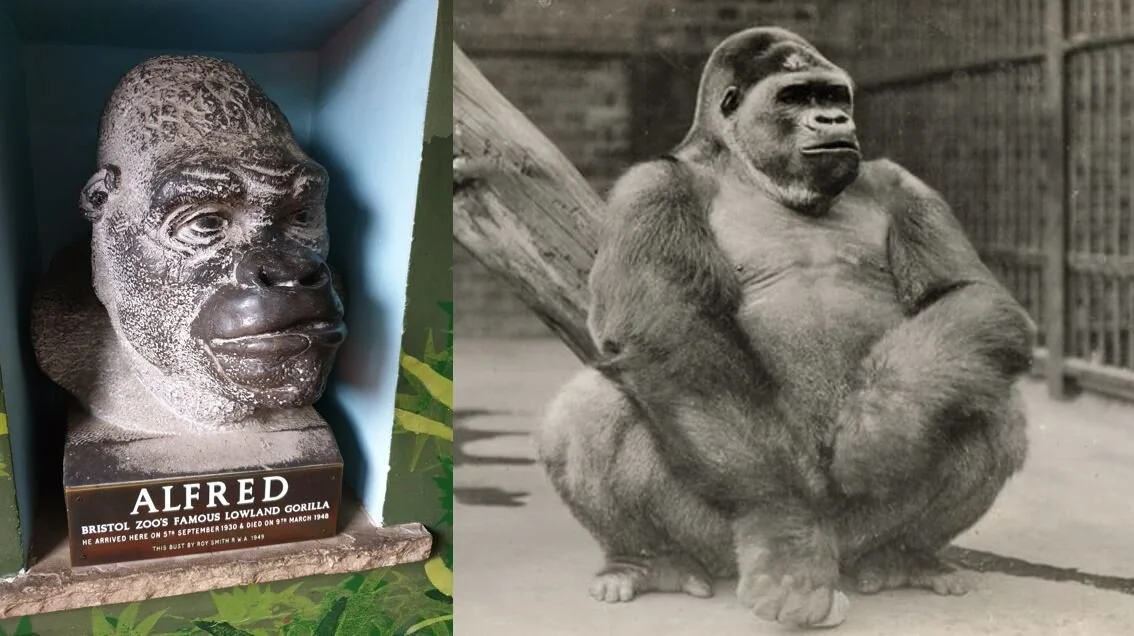

Caption: Bristol Zoo features quite a few statues and other installations in its grounds. I don’t have any good photos of live gorillas, but at least I photographed this statue. Image: Darren Naish.

Also of historic interest is that the zoo was among the first in Europe to house a gorilla: this being the famous Alfred the Western lowland gorilla Gorilla gorilla gorilla*, who was there between 1930 and his death (due to tuberculosis) in 1948. During his life, he was apparently thought to be a Mountain gorilla. That seems remarkable today but reflects how little information was available on gorillas at the time. A taxiderm mount of Alfred is today on show at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (meaning that his hairs, potentially, are available for DNA analysis**).

* Well, this is the favoured identification, but it hasn’t been definitively confirmed to my knowledge (or has it?). He’s said to have originated in what’s now the DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) which has Western lowlands in the far west and Mountain gorillas, of course, in the mountainous east.

** It’s said (I think I heard gorilla expert Esteban Sarmiento say it) that it’s unusually difficult to extract DNA from gorilla hairs.

Caption: a bust of the zoo’s famous gorilla Alfred. At right, an archive photo of Alfred, probably from the 1940s. Images: Darren Naish; Bristol Zoological Society.

The zoo is square, with a large lake near its centre, a series of tropical houses round its edges, and a large gorilla-themed feature taking up much of its north-east corner. As you might predict given my comments above, it’s a mix of old-fashioned, less-than-ideal enclosures with a bunch of modern stuff that’s very nicely designed.

Mid-sized mammals. A number of large and mid-sized mammals are on show throughout, including Asiatic lion Panthera leo leo, Red panda Ailurus fulgens and Two-toed sloth Choloepus didactylus close to the entrance, and Ring-tailed lemur Lemur catta, Visayan warty pig Sus cebifrons nigirnus and Pygmy hippo Choeropsis liberiensis elsewhere. Brazilian tapir Tapirus terrestris were there in recent years (2009 at least) but don’t seem to be there now.

Caption: Brazilian tapirs at the zoo in 2009, here demonstrating how tame and friendly they can be. Long-time readers might recall me using these photos when discussing tapir attacks: go here for one of those articles. Images: Darren Naish.

Zoo favourites like meerkats and otters are there too, though the otters are (or were) American river otter Lontra canadensis rather than the ubiquitous little clawless bastards. I don’t recall seeing otters on my more recent visit and am not sure if they’re still there. Some of the enclosures are notably on the small size for the animals, the Asiatic lions in particular.

Caption: the zoo’s Pygmy hippo - a female called Sirana - hasn’t been showing when I’ve visited. Here’s the ‘best’ of my photos. Great. Sirana is due to move (or has already moved) to the Gulf Breeze Zoo in Florida. Images: Darren Naish.

The zoo’s best mammals (for me) are the Goodfellow’s tree kangaroos Dendrolagus goodfellowi, which have been there since 2017 and occupy a new and specially constructed enclosure with good climbing space and a glass-fronted indoor viewing area. One of the kangaroos was extremely mobile during my November 2019 visit, repeatedly visiting a wooden door in the indoor part of its enclosure and rubbing its chest against it. As you can see from the photos here, this is clearly a favoured rubbing spot as it’s covered in a thick, dark oily stain. While writing this article I learnt that one of the zoo’s kangaroos became ill and had to be euthanized in 2020.

Caption: shots of one of the zoo’s very cooperative tree kangaroos (contrast very much upped as the lighting was terrible). I was really taken with the animal’s extremely long, slender, attractively patterned tail. Images: Darren Naish.

A highlight for anyone really interested in mammals is the Twilight World exhibit. This opened in 1996 (it’s another retooled building, having been initially constructed as a primate house) and is best known for housing Aye-aye Daubentonia madagascariensis. I had superb views of one of the zoo’s aye-ayes during a 2009 visit when the animal spent time right in front of a viewing window and even had a brief altercation with one of the Vontsotsa Hypogeomys antimena in the same exhibit (sadly, no photos). Alas, the house was closed during my more recent trip.

While I’m not completely sure what’s in the Twilight World exhibit right now, they’ve had an impressive list of small mammals within recent years, among which are quolls, potoroos, cuscus, mole rats, Asian hamsters, kangaroo rats, dwarf lemurs, slow loris and chevrotain. It’s not just mammals: Twilight World also houses assorted reptiles (including Aruba Island rattlesnake Crotalus unicolor and Gila monster Heloderma suspectum), and arthropods too.

Caption: mammals that were on show in 2009, but seem not to be at the zoo today: prairie dogs and drill. The drill photo was taken through a window and from some distance, but it’s the best I have. Images: Darren Naish.

A lot of primates. The zoo is home to a group of eight Western lowland gorillas who have a large, well vegetated island and modern building as a home. They’ve had three births in recent years (2016, 2017 and 2020), one of which was delivered via caesarean section. Enclosures nearby house other primate species, including Crowned lemur Eulemur coronatus (an endangered species), Brown spider monkey Ateles hybridus (a critically endangered species with less than a few hundred left), Black howler monkey Alouatta caraya, Common squirrel monkey Saimiri sciureus*, Golden-headed lion tamarin Leontopithecus chrysomelas (an endangered species which the zoo has recently bred), Lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus (also endangered) and Agile gibbon Hylobates agilis (also endangered). There were Drills Mandrillus leucophaeus when I visited in 2009 (they bred at the zoo in 2015) but I don’t think they’re there now. If memory serves, they were kept in one of the old Victorian enclosures no longer deemed properly appropriate.

* Presumably Guianan squirrel monkey, since the ‘Common squirrel monkey’ now seems to be a species complex (Alfaro et al. 2015).

Caption: most of my primate photos from Bristol Zoo are poor. From left to right: the terribly named Lion-tailed macaque, what I think are Ebony langur Trachypithecus auratus (no longer at the zoo; photo from 2009), and Ring-tailed lemurs (with David Hone visible; he’s the one with the dark hair and red t-shirt). Images: Darren Naish.

This is a significant and exciting primate collection that features a good number of species rarely seen in European collections, the bulk of which are endangered and with global populations in the low thousands or hundreds. I haven’t ever had time during my visits to spend proper time looking at Bristol Zoo’s primates – there’s simply so much other stuff to look at (read on).

Caption: lemurs on show at Bristol Zoo in 2009… I think they’re Mongoose lemurs Eulemur mongoz, a species that might not be at the zoo right now (though I could be wrong) Image: Darren Naish.

An excellent Reptile House and aquarium. Another personal highlight of the zoo is the large, recently constructed Reptile House. Reptile Houses tend to be bland, concrete-dominated boxes that feel like brutalist underground carparks, Cold War Era nuclear bunkers or Victorian prisons but Bristol has very deliberately moved away from this, with slatted wood ceilings, stonework walls, glass skylights, extensive greenery throughout (even outside the enclosures) and large, glass-fronted display areas that feel more like landscaped animal enclosures than old fish-tanks. The signage in the Reptile House is excellent: modern and clear.

Caption: one view of the Reptile House interior. The big buttress root at lower right is of course artificial but there’s a lot of good plant growth in there. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: the small but deadly frog so famous for being able to kill thousands and thousands of mice… if only it had the chance. I wrote an article about this frog: go here. Image: Darren Naish.

It houses many fairly familiar species (including Golden poison frog Phyllobates terribilis and Blue poison dart frog Dendrobates azureus) as well as some fairly unfamiliar ones (like Trinidad stream frog Mannophryne trinitatus, Malaysian giant turtle Orlitia borneensis, Black marsh turtle Siebenrockiella crassicollis, Bourret’s box turtle Cuora bourreti, Bearded pygmy chameleon Rieppeleon brevicaudatus and Cuban boa Chilabothrus angulifer). I was really taken with the turtle collection and have spent way too much time trying to get half-decent photos, especially of the amazing Orlitia. This is a huge, omnivorous geoemydid turtle that’s threatened by illegal poaching and the encroaching of palm oil plantations.

Caption: the zoo has a pretty good turtle collection, with several species on show that you probably haven’t seen before. They include (at left) Black marsh turtle and African pancake tortoise Malacochersus tornieri. Images: Darren Naish.

Caption: a squamate montage, Bearded pygmy chameleon at left and Cuban boa at right. I’m among the privileged few who’ve met the Rieppel after whom Rieppeleon is named. Image: Darren Naish.

I also especially like the large enclosures housing Amethystine python Simalia amethistina, Chinese crocodile lizard Shinisaurus crocodilurus and Solomon Islands skink Corucia zebrata (for more on that animal, go here). A pool (with beach area) in the middle of the building is home to West African dwarf crocodile… so, Osteolaemus tetraspis, right? As I said in my ZSL Whipsnade review, we think today that O. tetraspis of tradition is a species complex (Smolensky 2015). What does this mean for the Bristol Zoo animals? I’m reliably informed that they appear to originate from as as-yet-undescribed wild population that (phylogenetically speaking) is outside of O. tetraspis in the new, restricted sense.

Caption: Shinisaurus has to be one of the coolest looking of living lizards. This animal was totally unknown to those of us in the west until a few decades ago (it was only made known to science in 1930). Now it’s in many captive collections. It’s endangered and disappearing fast in the wild. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: the zoo’s large Amethystine python in its very nicely landscaped enclosure. Amethystine or Scrub pythons can be giants, in cases exceeding 5 m. I recall that one especially big wild-living individual was named Scrubby. Good work, Australia. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: a West African dwarf crocodile at Bristol Zoo, a crocodile of the sort that we’d previously have lumped into Osteolaemus tetraspis. Image: Darren Naish.

Adjacent to the Reptile House is a similarly modern and well-designed aquarium, the large glass-fronted enclosures of which (I can’t bring myself to call them ‘tanks’) are well constructed and planted, and look great. They feature a charismatic list of ‘best ofs’ including gar (of three species!), paddlefish, sturgeon, assorted catfishes, knifefishes, freshwater stingrays and mudskippers as well as New Guinea pig-nosed turtle Carettochelys insculpta.

Caption: gar and sturgeon in the zoo’s aquarium. Sorry for the saturation; I had to mess with the contrast a lot to reduce the glare on the glass. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Carettochelys, the famous New Guinea pig-nosed turtle. This image provides a reasonable view of its very interesting forelimb. Image: Darren Naish.

Close by and in a separate building are the Aldabran giant tortoises Aldabrachelys gigantea, named Helen, Biggy, Twiggy and Mike. They’re great fun… when they’re doing something instead of lying down. There used to be Rhinoceros iguana Cyclura cornuta together with the tortoises but I see that they’re now on show in the Reptile House.

Caption: a photo that needs an amusing caption… one of these Aldabran giants has evidently just told a joke. Image: Darren Naish.

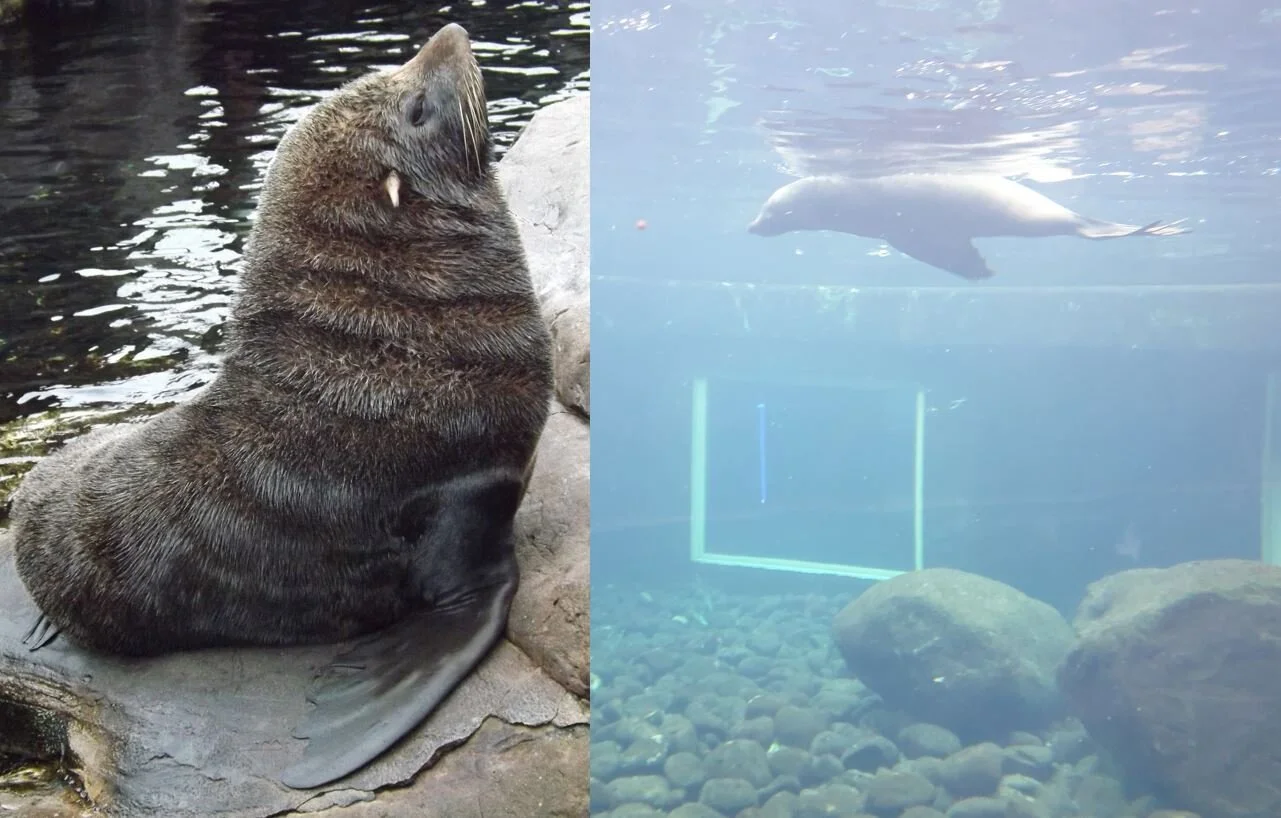

A marine zone. Another highlight for me is the Seal and Penguin Coasts, a mock rocky sea-edge area that consists of some deep, connected pools surrounded by pebbly shores and rocky escarpments, and with an underwater viewing tunnel that you access by going underground. The stars of the show are of course the African penguins and South American fur seals Arctocephalus australis (very much kept separate, of course), but Common eider Somateria molissima and free-flying Inca terns Larosterna inca are there too.

Caption: African penguins building a stick nest (you see, not all penguins build nests made of stones). Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: a view from one of the walkways of the very nicely constructed Seal and Penguins Coasts exhibit, this time without any eider or terns in shot. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: an odd feature of fur seal (and other otariid) species is that they routinely rest with the head pointing skywards. I wonder if there’s an anatomical reason for this and if anyone has studied it. Anyway: at left we see one of the fur seals hauled out on land, and on right a view from the underwater viewing area. Image: Darren Naish.

I absolutely adore the fake rock displays and pebble shore here, though in the same breath you have to note that the area containing these features is small, though not definitely too small for the birds they have. The fur seals do have a reasonably large area in which to swim, but it does feel cramped after a while. Indeed, the crowded nature and small size of the zoo is evident from the fact that you can see houses and other buildings looming large in the background behind Inca terns.

Caption: a nice action shot of some of the zoo’s Inca terns, showing them variously standing there and doing nothing or engaging in what I presume is a courtship display. Image: Darren Naish.

In 2018, the zoo’s oldest fur seal – Otari (ha ha) – died at the age of 17. Pinnipeds have lifespans in the same sort of ballpark as the carnivorans we keep as pets, so survival into late teen years is very good and anything over 20 is potentially record-breaking.

Closing thoughts. Finally, I should add briefly that the zoo also has a walk-through Butterfly Forest and Forest of Birds exhibit, several additional outdoor aviaries (housing lovebirds, lorikeets, amazons and others; there were Azure-winged magpies Cyanopica cyanus – that’s the Asian one, not the Iberian one now known as C. cooki – and I think hoopoes on one of my visits), and a very nicely landscaped flamingo-themed aviary. This doesn’t just have flamingos, but also avocets and assorted wildfowl. I won’t start talking about the ducks or I’ll never finish this article. It’s a great exhibit if you’re interested in birds.

Caption: birds photographed at the zoo in 2009 (and perhaps not there now? I’m not sure): Crested pigeon Ociphaps lophotes and Azure-winged magpie. Image: Darren Naish.

Finally finally, the leafiness of the zoo is part of its appeal to me. I want zoos to create the impression that you’re in recreated or even restored natural environments, not places dominated by concrete and steel, and Bristol Zoo scores well on this front. My most recent visit was in November (2019) so many of the trees were shedding their leaves, or still in their autumnal colours… which is a good look if you like that sort of thing.

Caption: Bristol Zoo is not that big, but it’s big enough to include well-vegetated area like this (around some of the primate islands). Image: Darren Naish.

And that ends my review. It will be sad to see Bristol Zoo close. As should be obvious from my article here, it’s had a rich and successful history of breeding endangered animals, of putting remarkable and often rare animals on show, and of putting Bristol itself in the national spotlight. Significant conservation work has been at the forefront for years, and the zoo has done what it can to improve and update its Victorian façade to something more modern and more appropriate for its needs. But, as I said, the zoo’s closure in 2022 will not be the end, but the start of a new chapter. Here are my entirely subjective scores…

Selection of species: 8 out of 10

Zoo nerd highlights: tree kangaroo, aye-aye, turtles Orlitia and Siebenrockiella

Quality of signage: 8 out of 10

Value for money: 9 out of 10

Overall worthiness: 9 out of 10

For previous articles in my zoo reviews series, and articles relevant to some of the topics touched on here, see…

Britain: wildlife theme-park, December 2007

Tet Zoo Reviews Zoos: Edinburgh Zoo, August 2016

The Terrible Leaf Walker Frog (on Phyllobates), May 2017

Tet Zoo Reviews Zoos: Colchester Zoo, October 2017

TetZoo Reviews Zoos: the Isle of Wight Zoo, February 2020

Corucia of the Solomon Islands, Most Amazing of Skinks, February 2020

TetZoo Reviews Zoos: ZSL Whipsnade Zoo, June 2021

If you like what I do and want to support it, please consider checking in at patreon - thanks!

Refs - -

Alfaro, J. W. L., Boubli, J. P., Paim, F. P., Ribas, C. C., da Silva, M. N. F., Messias, M. R., Röhe, F., Mercês, M. P., Silva Júnior, J. S., Silva, C. R., Pinho, G. M., Koshkarian, G., Nguyen, M. T. T., Harada, M.L., Rabelo, R. M., Queiroz, H. L., Alfaro, M. E. & Farias, I. P. 2015. Biogeography of squirrel monkeys (genus Saimiri): South-central Amazon origin and rapid pan-Amazonian diversification of a lowland primate. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 82, 436-454.