I’m a big fan of the fact that views on a given topic develop piecemeal…

Caption: Prehistoric Planet promotes Azhdarchid Supremacy. © Apple TV.

… that short bursts of dialogue and argument – occurring over decades – are crucial in the construction of a case, and that only after years and years of slow, incremental addition can we look back and realise how far we’ve come. Big, ‘game changer’ discoveries are great, of course, but we need to appreciate, too, that paradigm shifts take time and the accruing of relatively small bits of data.

Over the last few decades, our knowledge of one of my favourite groups of animals – the often gigantic, long-skulled azhdarchid pterosaurs – has improved substantially, and I say this as someone lucky enough to have been involved in research on this group. Writing (as ever) from a biased personal perspective, I thought it would be interesting to chart ‘azhdarchid progress’ as I’ve seen it from my own research interests. The words here are mostly recycled from the summary texts published at my publications site, but I decided it would be useful to have them together. I owe thanks to the other researchers I’ve collaborated with, in particular Mark Witton and the late Mátyás Vremir.

Caption: this life reconstruction of a foraging Quetzalcoatlus group accompanied Witton & Naish (2008). It’s a very dated image today and Mark probably won’t enjoy the fact that I’m sharing it (sorry Mark). But it’s significant in the story told here, since it was widely shared in news articles reporting our 2008 conclusions. It probably is, in fact, one of the most widely shared, most often reproduced, azhdarchid-themed images. Image: Mark Witton, from Witton & Naish (2008).

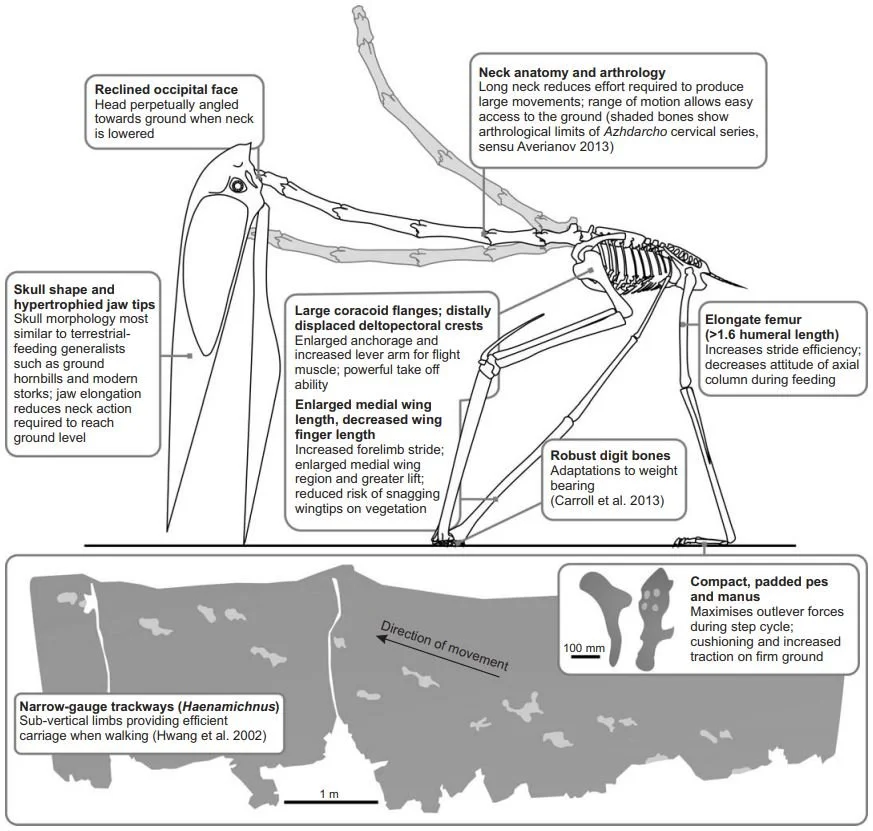

The ‘terrestrial stalking’ paradigm. Azhdarchids have to be regarded as the most distinctive and unusual of pterosaur groups, and views on how they might have lived have varied considerably. In our opening salvo published in 2008, Mark Witton and I examined the skeletal proportions, cranial anatomy and sedimentological setting of azhdarchids and concluded that they were strongly adapted for quadrupedal walking in terrestrial settings (Witton & Naish 2008). They were likely striding predators of small and mid-sized prey, analogous to modern ground hornbills. We termed this the ‘terrestrial stalking’ model. Our proposal has been supported by additional studies (Witton & Naish 2015, Naish & Witton 2017). Some minor pushback came from other pterosaur specialists, on which read on…

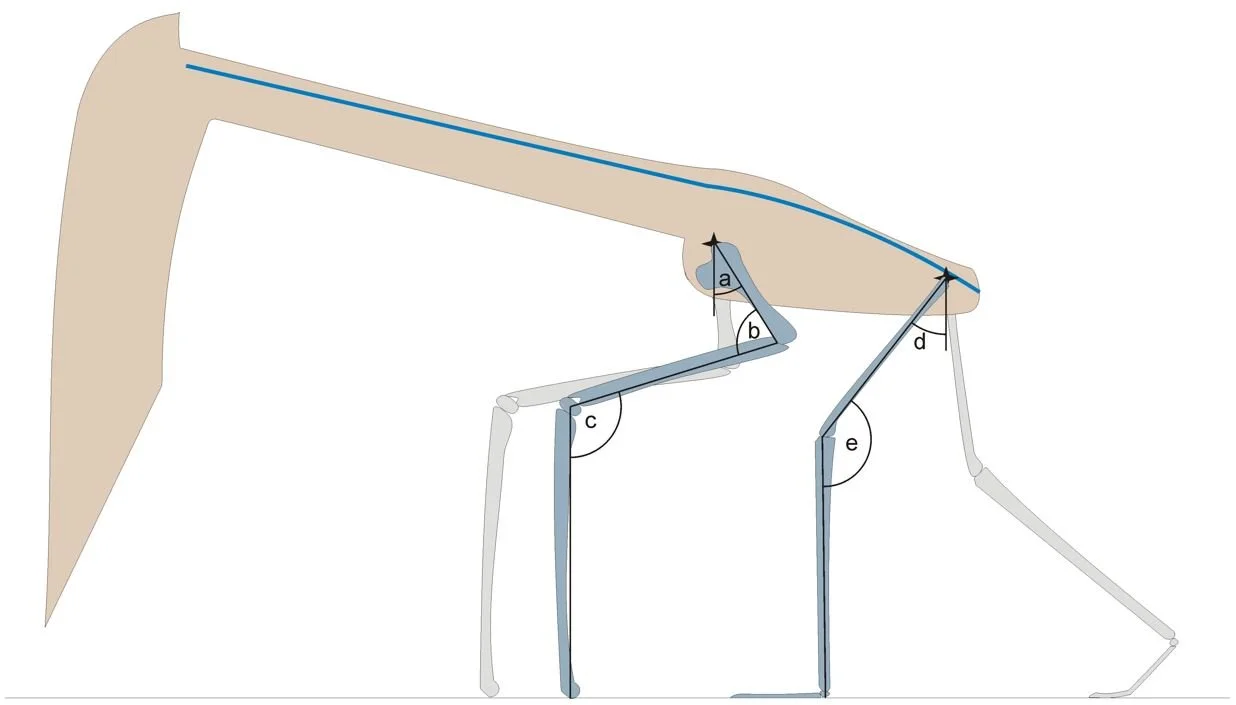

Caption: this diagram, from Witton & Naish (2008), shows how joint flexion in the fore- and hindlimbs of an idealized azhdarchid (this is the Chinese form Zhejiangopterus) allows these otherwise very leggy animals to reach the ground with their jaw tips. Image: Mark Witton, from Witton & Naish (2008).

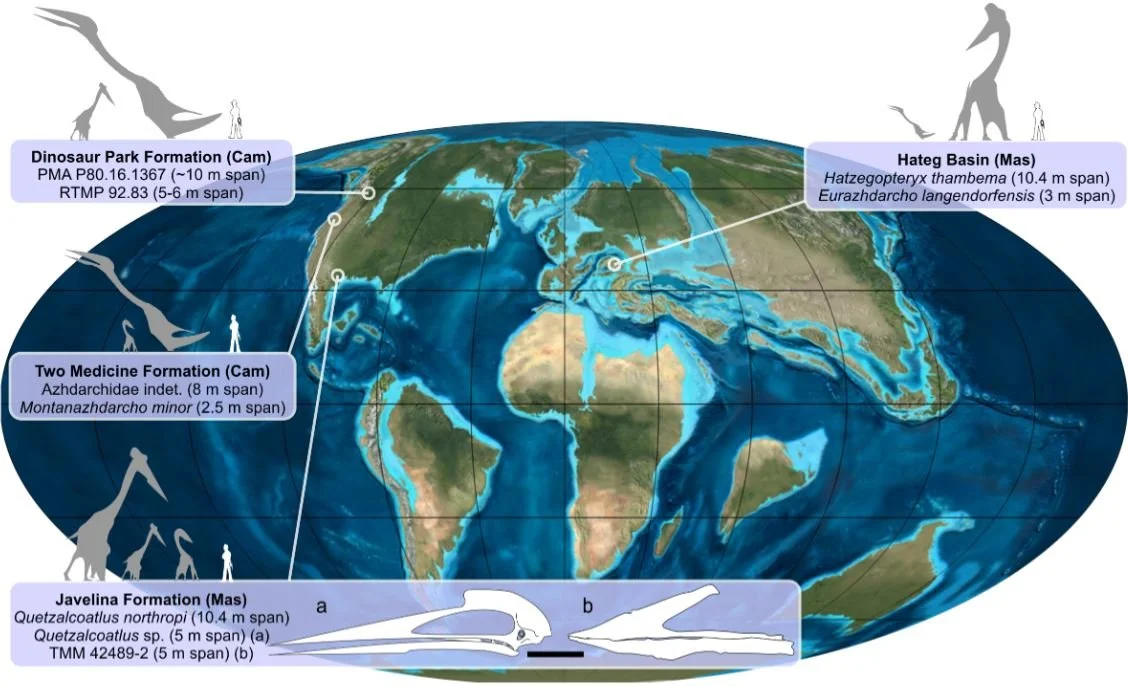

Sympatry and niche partitioning was probably normal in azhdarchids. In a project resulting from collaboration on the vertebrate palaeontology of the Romanian Late Cretaceous, I and colleagues described a new azhdarchid – Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis Vremir et al., 2013 – represented by cervical vertebrae and part of the wing skeleton. The specimen is represented by adult remains and is not a juvenile specimen of the much larger Romanian azhdarchid Hatzegopteryx (Vremir et al. 2013). The presence of both of these azhdarchids in the same geological unit (the Sebeş Formation of the Transylvanian Basin) is significant, since it indicates that niche partitioning was present in sympatric azhdarchids. We noted the presence of several locations worldwide where sympatric azhdarchids occur, these taxa differing in size and hence presumably in ecology and habits. Eurazhdarcho is one of many new taxa discovered by Mátyás Vremir (who died in 2020).

Caption: some geological units reveal evidence of two or even three sympatric azhdarchid species. Since this diagram was published, one of the Dinosaur Park Formation azhdarchids has been named Cryodrakon boreas, and the Javelina Formation has two additional azhdarchids (Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni and Wellnhopterus brevirostris). Diagram produced by Mark Witton and map used with kind permission of Ron Blakey, Colorado Plateau Geosystems, Inc; from Vremir et al. (2013).

Some azharchids had ‘short’ necks. The idea that azhdarchid pterosaurs were anatomically homogenous – an assumption more or less inherent to Witton & Naish (2008) – is challenged by several poorly known taxa. These indicate that neck length and proportions, and body size overall, was variable in the group (an idea first mooted by Dave Unwin in his 2006 book The Pterosaurs From Deep Time). In this paper, we described LPB (FGGUB) R.2395, a Haţeg Basin cervical vertebra from a mid-sized azhdarchid, estimated to have a wingspan of 3-4 m (Vremir et al. 2015). Despite its small size (89 mm long), its smooth (non-pitted), polished external bone texture shows that it belonged to an adult. It’s probably a cervical IV.

Caption: the Romanian azhdarchid neck vertebra R.2395 is one of several specimens which helped reveal that this group includes relatively short-necked forms in addition to the more familiar, giraffe-necked kinds like Quetzalcoatlus. R.2395 represents an additional taxon that lived alongside the very different Eurazhdarcho and Hatzegopteryx, but it hasn’t yet been named. Another azhdarchid (Albadraco) has been named from the Maastrichtian of Romania (albeit from a different faunal assemblage) and doesn’t appear to represent the same taxon as R.2395. The life reconstruction shown here is, of course, speculative. Images: Mark Witton; Vremir et al. (2015).

The most interesting thing about R.2395 is that it is relatively broad for its length, this indicating that the animal had a neck length c 30-40% shorter than that of other azhdarchids of similar size. It indicates the presence of an additional azhdarchid taxon in the Haţeg Basin fauna (Vremir et al. 2015). We also argued in this paper that efforts to sink all Haţeg Basin azhdarchids into a single taxon do not withstand scrutiny. Due to an editorial mishap, the final published version of this paper is not as richly illustrated as planned in earlier drafts.

More thorough support for ‘terrestrial stalking’. The view that azhdarchid pterosaurs were ‘terrestrial stalkers’, proposed by Witton & Naish (2008), was challenged in 2013 by Alexander Averianov. Averianov argued that the depositional settings of azhdarchid fossils were inconsistent with our proposal, that big theropods made our proposal problematic, and that azhdarchids were more likely ‘scoop-netters’. In our response, Mark Witton and I re-examined the environmental context in which azhdarchids have been discovered and showed that the evidence was consistent with them being animals of continental settings (Witton & Naish 2015). We also looked at the behaviour and ecology of those theropods contemporaneous with azhdarchids to see if they would really present the problem that Averianov argued they would, and examined his ‘scoop-netting’ idea in order to test its viability (Witton & Naish 2015).

Caption: the terrestrial stalking hypothesis is based on multiple lines of evidence. It does not (like so many other hypotheses about pterosaur behaviour and ecology) rely on cherry-picking one or two anatomical or palaeoenvironmental features. This image – from Witton & Naish (2015) – shows how several independent pieces of data all provide support for our hypothesis.

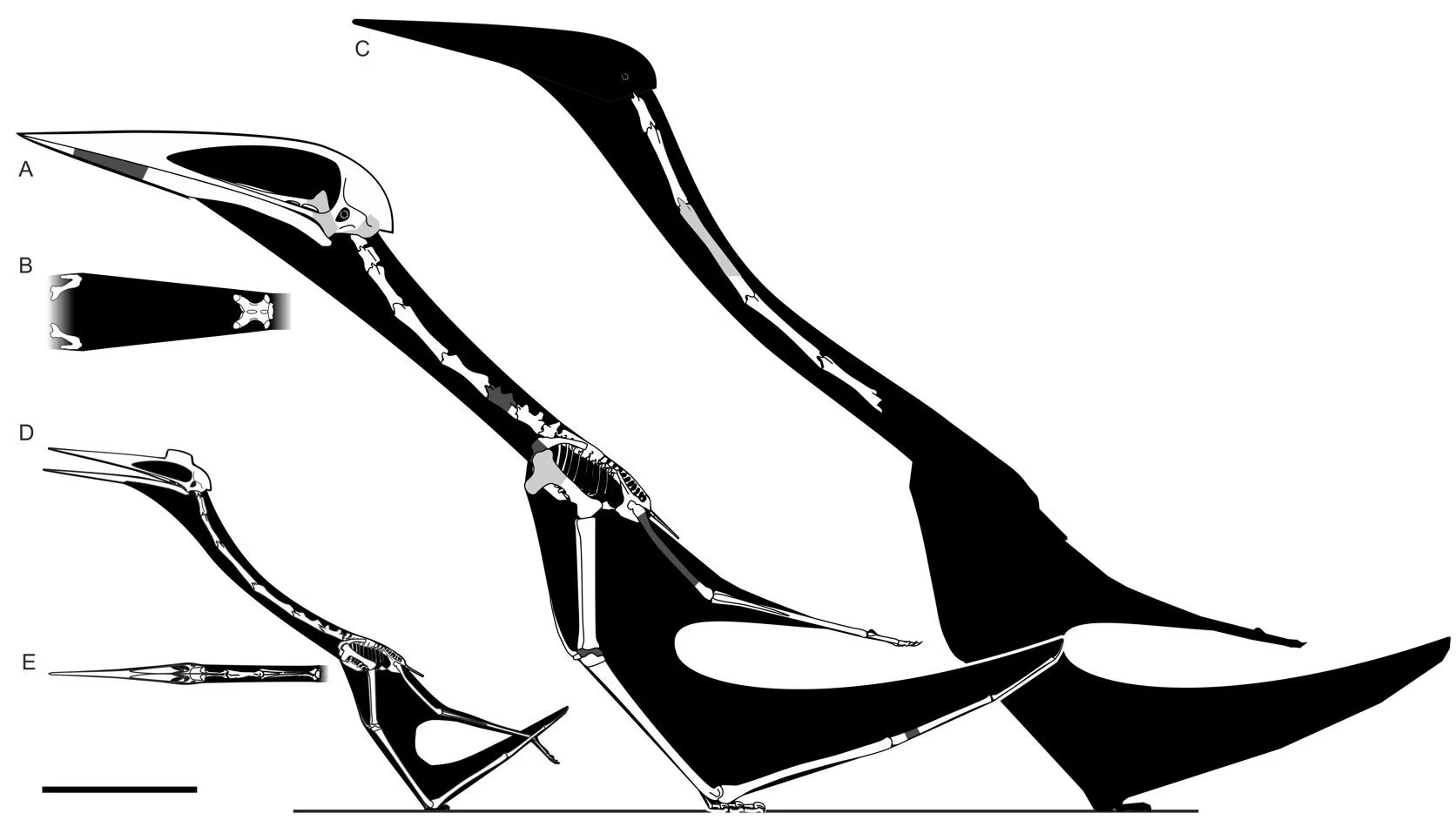

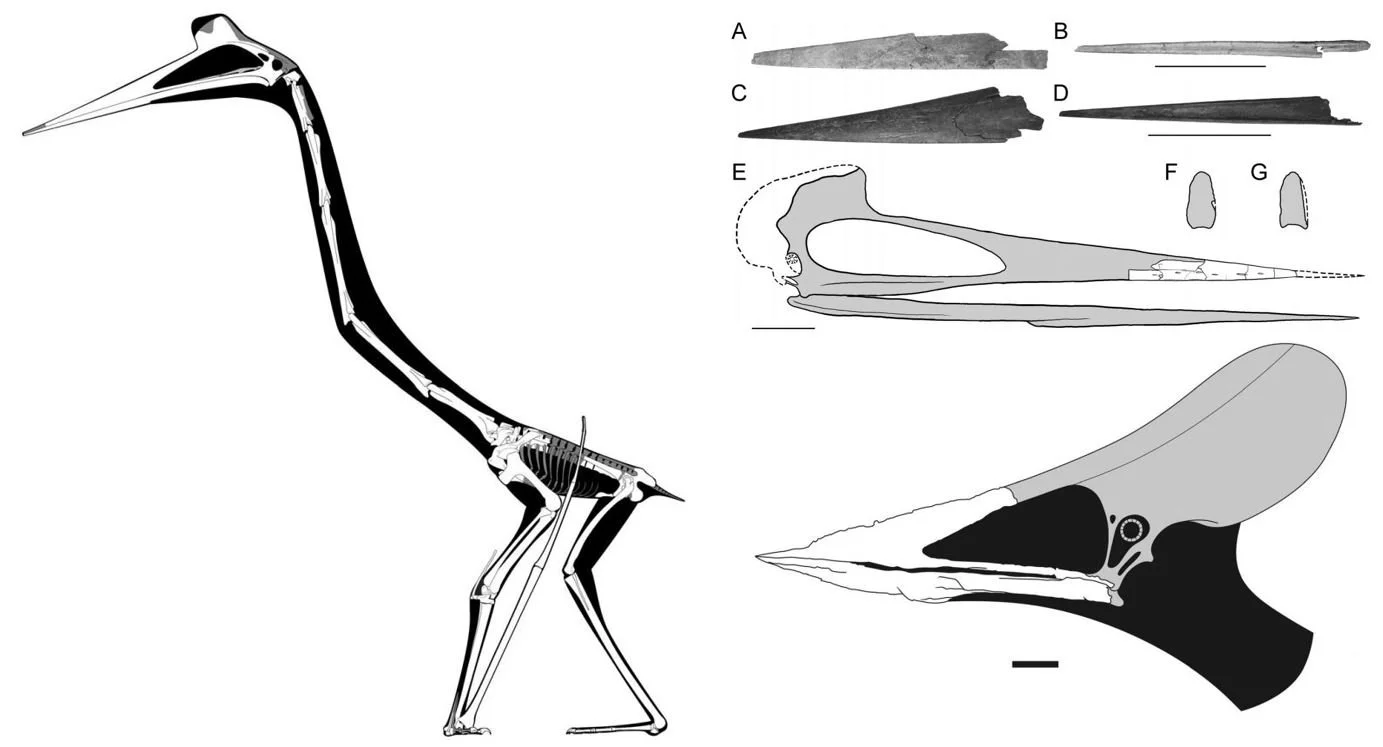

Some azhdarchids were giant, thick-necked predators. The view assumed in the writing of Witton & Naish (2008) and Witton & Naish (2015) – that azhdarchids were essentially alike in proportions and hence similar in lifestyle – was again shown to be incorrect via our 2017 analysis of cervical vertebrae belonging to the giant Late Cretaceous Romanian azhdarchid Hatzegopteryx. We showed that the neck of this animal was broad and thick relative to that of other giant azhdarchids (like Arambourgiania) and mechanically able to resist substantial loads (Naish & Witton 2017).

Caption: skeletal reconstructions of the giant azhdarchids (A) Hatzegopteryx and (C) Arambourgiania to scale, showing the markedly different body shapes of these animals. (B) shows how broad the back of the skull and neck was in Hatzegopteryx. Contrast this with D-E: the small Quezalcoatlus species, with its 4.6 m wingspan and long, slender neck. Scale bar = 1 m. Credit: Naish & Witton 2017.

This view is consistent with the absence of large predators (like theropods) from the same region and suggests that Hatzegopteryx was a predator of animals that could have weighed tens of kilos. This study is consistent with our previous proposal (Vremir et al. 2015) that some azhdarchids were relatively short-necked.

Finally…. what else? The research discussed here focuses on North American, Afro-Arabian and eastern European azhdarchids, but this is a group with a near-global distribution. In addition, the iconic North American taxon Quetzalcoatlus was (at least in terms of technically published data) poorly known throughout the entire time that the studies discussed above were being compiled and published, this hindering our understanding of azhdarchid anatomy and phylogeny. In late 2021, the long-awaited monograph on Quetzalcoatlus was finally published, meaning that this was a good time to round up recent discoveries from the azhdarchid world and look at then-current views on their diversity and phylogeny.

Caption: montage depicting some azhdarchid finds and publications of the 2010s and 20s. At left, the new reconstruction of Quetzalcoatlus published by Padian et al. (2021). There’s some controversy over the accuracy of this image, since an argument has been made that the hindlimbs have been made too long. At upper right, a montage from Novas et al. (2012) showing the mid-sized Argentinian Aerotitan (A and B, and reconstructed in E) compared to the Moroccan Alanqa (C and D; Alanqa is now regarded by some authors as being outside of Azhdarchidae, and within the separate group Alanqidae). At lower right, a speculative reconstruction of Wellnhopterus, depicting this animal as a thalassodromid, from Campos (2021). Scale bar = 10 cm.

Many basic questions about the biology, ecology, distribution and anatomy of these animals remain, and there’s tons of science left to do. I’m one of many people aiming to publish on them again, and with new data, new ideas, and new hypotheses. Those things will emerge in time. But the point of this article is that we have – I contend – turned a metaphorical corner in terms of what we think azhdarchids were like, and that, I put it, is significant.

For previous TetZoo articles on azhdarchids and other pterosaurs, see…

Tiny pterosaurs and pac-man frogs from hell, March 2008

Daisy’s Isle of Wight Dragon and why China has what Europe does not, March 2013

In Rio for the 2013 International Symposium on Pterosaurs, May 2013

Quetzalcoatlus: the evil, pin-headed, toothy nightmare monster that wants to eat your soul, August 2013

Were azhdarchid pterosaurs really terrestrial stalkers? The evidence says yes, yes they (probably) were, December 2013

Some Azhdarchid Pterosaurs Were Robust-Necked Top-Tier Predators, February 2017

Postcranial Palaeoneurology and the Lifestyles of Pterosaurs, August 2018

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology, the TetZoo Review, September 2020

Baby Pterosaurs Were Excellent Fliers and Occupied Different Niches From Their Parents, July 2021

The Quetz Monograph Lives and Other News on Azhdarchid Pterosaurs, December 2021

Refs - -

Campos, H. B. N. 2021. A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation of Texas. Biologia doi: 10.1007/s11756-021-00841-7.

Novas, F. E., Kundrát, M., Agnolín, F. L., Ezcurra, M. D., Ahlberg, P. E., Iasi, M. P., Arriagada, A. & Chafrat, P. 2012. A new large pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 32, 1447-1452.