Let’s talk about Malawania!

Caption: Bob Nicholls's life restoration of Malawania, coloured by C. M. Kösemen.

Back in 2013, myself and a team of colleagues published the new Iraqi ichthyosaur Malawania anachronus (Fischer et al. 2013a). And at that year’s Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting, held in Los Angeles, we presented a poster on the specimen (Naish et al. 2013)…which I sadly no longer own (shame, as I quite liked its design). In the interests of recycling material, here’s the text from said poster – partly published here at TetZoo because I have no time to produce anything new, but also partly because I currently have Mesozoic marine reptiles on my mind due to an exciting new project.

Caption: I don’t own the poster anymore, but I least I still have the powerpoint files. A formatting error that I can’t correct has ruined the text in the middle of the poster, d’oh.

Long-time readers might know that Malawania has been covered at TetZoo before (see links below). I should also note here that the text doesn’t tell the full Malawania story at all, in particular the massive amount of behind-the-scenes work that happened as the late Robert Appleby tried, for decades, to get his paper on the specimen published, and then the post-Appleby phase in which Jeff Liston worked hard to resuscitate interest in the specimen and get it into print. Anyway, to business…

In 1952, a team of British oil geologists (D. M. Morton, F. R. S. Henson, R. J. Wetzel and L. C. F. Damesin) discovered the articulated anterior half of an ichthyosaur (lacking the rostrum) at Chia Gara, Armadia, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. The specimen was preserved on a large slab that had been transported an unknown distance and was being used to dam a small river and as a stepping-stone for a track. People and pack animals were thus routinely walking over the fossil. Preliminary preparation was undertaken in the field.

Caption: the Malawania holotype as it originally appeared, in the field. Some quick and dirty preparation was carried out in-situ.

Morton and colleagues recognised the potential significance of the specimen and transported it back to the UK, donating it in 1959 to the Natural History Museum, London. In several respects, the specimen is ‘archaic’, appearing similar to the Lower Jurassic west European thunnosaurian Ichthyosaurus. Its forefin bones form a tightly packed mosaic of hexagonal elements and the forefin itself is tetradactyl and lacks accessory digits, notching is present on the leading digit, and the scapula lacks a prominent acromion. The discovery of the specimen on an isolated slab of matrix meant that stratigraphic origin was not obvious: initial suspicions were that it ‘must’ have come from the Sargelu Formation and was either Middle or Upper Jurassic in age. The first plant microfossils extracted from the slab’s matrix were said to indicate a Lower Cretaceous origin. A renewed effort to extract microfossils and hence resolve the age of the specimen revealed taxa unique to the Hauterivian and Barremian parts of the Early Cretaceous. Given the Ichthyosaurus-like form of the Iraqi taxon, it has to be regarded as an anachronism: a thunnosaurian of Lower Jurassic grade that persisted into the Cretaceous.

Caption: Jeff Liston took a chunk of matrix from the Malawania block (marked by the dotted line) and then worked with others to extract microfossils. We received quite a shock when the results arrived — the relevant fossils are categorically from the Early Cretaceous.

A ‘Lower Jurassic’ Ichthyosaur in the Cretaceous

The Iraqi thunnosaurian is only the second ichthyosaur to be reported from the Middle East (the first is an indeterminate mixosaurid-like animal from Saudi Arabia: Vickers-Rich et al. 1999). It possesses several diagnostic characters: a horn-shaped projection on the posterodorsal part of the humerus, an especially short, squat humerus, and trapezoidal neural spines on the cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae (Fischer et al. 2013a). Accordingly, we have named it Malawania anachronus Fischer et al., 2013.

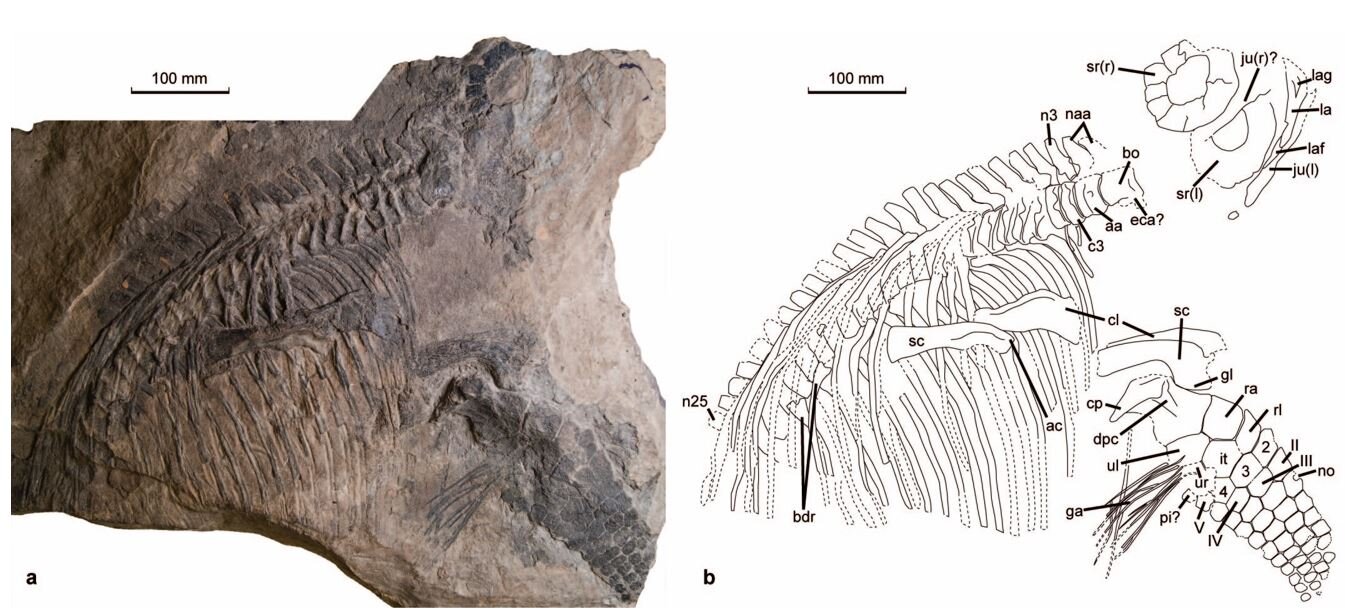

Caption: NHMUK PV R6682, the Malawania holotype, at left, and our interpretation of its anatomy at right. The specimen is partly lying on its back and left side, and we're looking 'up' into its ribcage. The forefin is a left one, seen in medial view. The cluster of spines near the forefin are actually gastralium segments.

Malawania is represented by an articulated partial skeleton consisting of the posterior part of the skull, much of the ribcage, articulated cervical and dorsal vertebrae, much of the shoulder girdle, and a complete left forefin.

A New Phylogeny for Parvipelvia

We included Malawania within a novel phylogenetic analysis, the largest compiled for Parvipelvia. Malawania was consistently recovered as the sister-taxon to Ichthyosaurus, a discovery which requires the existence of a c 70 Ma ghost lineage (Fischer et al. 2013a). We found parvipelvians to group into a lower number of larger radiations than previously proposed.

Caption: the new parvipelvian phylogeny published in Fischer et al. (2013b). Note the temnodontosaur + leptonectid clade, the long ghost lineage for Malawania, and the numerous ophthalmosaurid lineages that crossed the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary.

We also coded Malawania for inclusion in other published ichthyosaur analyses. Malawania was not consistently recovered as the Ichthyosaurus sister-taxon in all of the resulting trees (note, however, that character and taxon sampling in these other analyses is poorer than in ours). It was, however, consistently found to be outside of Ophthalmosauridae, and was frequently surrounded by taxa that belong to lineages with a Late Triassic or Early Jurassic origin.

Numerous ophthalmosaurid lineages (perhaps as many as 11) survived across the Jurassic-Cretaceous Boundary (JCB) (Druckenmiller & Maxwell 2010, Fisher et al. 2011a, b, 2012, 2013b, Zammit 2012). The discovery of Malawania shows that ophthalmosaurids were not the only ichthyosaurs to persist into the Cretaceous: close relatives of Ichthyosaurus did too (we opted to be conservative and have not used the name Ichthyosauridae for the Ichthyosaurus + Malawania clade, but this decision would seem justifiable).

Ophthalmosaurids were diverse, strongly pelagic, globally widespread, and gave rise to new species at a rapid rate. Meanwhile, members of the Malawania lineage were rare, low in diversity, and restricted in distribution. Furthermore, the apparent conservatism in Malawania’s lineage indicates a long evolutionary stasis – a contrast to the general trend seen elsewhere throughout Mesozoic marine reptiles whereby lineages appear to steadily and continually become more streamlined, more efficient, and more specialised for pelagic life throughout their history.

Caption: Malawania at left, the Jurassic-style Cretaceous ichthyosaur from Iraq. Compared to other Cretaceous ichthyosaurs - all of which are ophthalmosaurids, like the Acamptonectes shown at right - Malawania was an archaic ‘living fossil’ of its time. Illustrations by Robert Nicholls, coloured by C. M. Kösemen.

For previous TetZoo articles on ichthyosaurs, see…

The skin of ichthyosaurs, September 2008

Rigid Swimmer and the Cretaceous Ichthyosaur Revolution (part I), January 2012

Malawania from Iraq and the Cretaceous Ichthyosaur Revolution (part II), May 2013

Can’t get me enough of that sweet, sweet Temnodontosaurus, January 2014

Ancient Marine Reptiles Had Absurd, Complex Nostrils, July 2014

The Fall and Rise of Protoichthyosaurus, October 2017

The Ichthyosaurs of the Kimmeridge Clay, March 2021

Refs - -

Druckenmiller, P. S. & Maxwell, E. E. 2010. A new Lower Cretaceous (lower Albian) ichthyosaur genus from the Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47, 1037-1053.

Fischer, V., Arkhangelsky, M. S., Uspensky, G. N., Stenshin, I. M. & Godefroit. 2013b. A new Lower Cretaceous ichthyosaur from Russia reveals skull shape conservatism within Ophthalmosaurinae. Geological Magazine doi: 10.1017/S0016756812000994

Fischer, V., Clément, A., Guiomar, M., & Godefroit, P. 2011a. The first definite record of a Valanginian ichthyosaur and its implication for the evolution of post-Liassic Ichthyosauria. Cretaceous Research 32, 155-163.

Fischer, V., Masure, E., Arkhangelsky, M. S. & Godefroit, P. 2011b. A new Barremian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur from western Russia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology31, 1010-1025.

Naish, D., Fischer, V., Liston, J. & Godefroit, P. 2013. A basal thunnosaurian from Iraq reveals disparate phylogenetic origins for Cretaceous ichthyosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33, Supplement to 3, 183.

Vickers-Rich, P., Rich, T. H., Rieppel, O., Thulborn, R. A. & McClure, H. A. 1999. A Middle Triassic vertebrate fauna from the Jilh Formation, Saudi Arabia. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 213, 201-232.

Zammit, M. 2012. Cretaceous ichthyosaurs: dwindling diversity, or the Empire Strikes Back? Geosciences 2, 11-24.