In another effort to rescue old TetZoo material from the vandalized archives of ver 2 and 3, here’s a slightly revamped version of a 2009 article on hartebeest (the original version is here)…

Caption: hartebeest faces. At left, Jackson’s hartebeest or Lelwel hartebeest A. b. lelwel; a rare form now restricted to Kenya, Uganda and Chad. At right, Red or Cape hartebeest A. b. caama, a form of the far south. Like so many subspecies, the Red hartebeest was originally regarded as a distinct species, and still is by some. Those who do regard it as a species split it into two subspecies: A. caama caama (described in 1816 and extinct by 1940) and A. caama selbournei. Images: Steve Garvie, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here); (c) Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus are large, savannah-dwelling African antelopes. They are highly variable across their range, differing most obviously in colour (it varies from dark red with black patches to light golden brown) and horn shape. In some populations, the horns are widely spaced, relatively short and with backswept tips, while in others the horns have long, virtually conjoined bases (or pedicels), curve outwards, and then curve inwards at their tips, thereby forming a tall, lyre-like shape. Dutch settlers thought that the shape of the horns resembled that of a heart, hence the common name.

Caption: Swayne’s hartebeest or Korkay A. b. swaynei, photographed at a Senkelle Swayne’s Hartebeest Sanctuary in Ethiopia. Image: Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Though some controversy remains, it seems that the massive variation present among the many regional forms of hartebeest – about 70 taxa have been named, ranging across most of sub-Saharan Africa* – can all be accommodated within a single species, and indeed there are various hybrid zones where confusing intermediate morphologies are present (Ruxton & Schwarz 1929). Some authors have regarded Lichtenstein’s hartebeest or the Nkonzi A. b. lichtensteinii as a separate species that even warrants it own genus (Sigmoceros) but the bulk of evidence shows it to be another A. buselaphus subspecies. In overall shape, all hartebeest are alike: they are long-legged, short-necked alcelaphine antelopes with tall shoulders and very long, narrow faces.

* And, previously, north of the Sahara too. The ‘original’ hartebeest, the nominate form of the species, is the now extinct Bubal A. b. buselaphus, a semi-desert specialist and the smallest of all the hartebeest. Formerly widespread across northern Africa, it was hunted to extinction by about 1923 (or perhaps a little later).

Caption: Bubal hartebeest, as depicted by Joseph Smit for Philip Sclater’s The Book of Antelopes vol 1 of 1894. Photos of live, captive Bubal hartebeest are known, and wow it was an interesting animal. Image in the public domain.

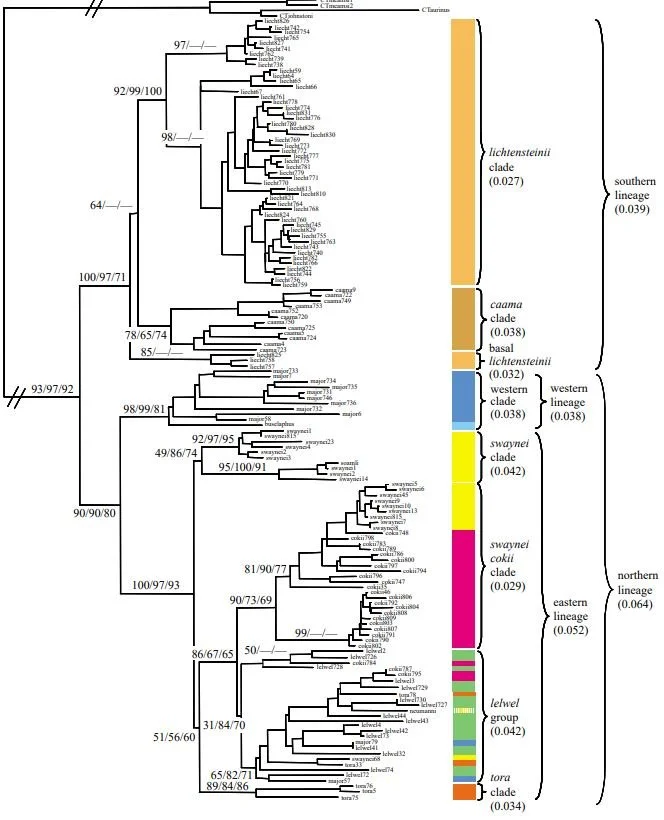

Out of the east. Kingdon (1997) proposed that the hartebeest with the short horn bases, like the Kongoni A. b. cokei, Korkay A. b. swaynei and Tora A. b. tora (all of which are from eastern Africa), are more primitive than the tall-pedicelled forms like the Khama (of the Kalahari) and Kanki A. b. major (of western Africa). Some of this is consistent with evidence from DNA but some of it isn’t. Molecular phylogenetics (Flagstad et al. 2001, 2004) indicates that hartebeest originated in eastern Africa and colonised the rest of the continent from there, a southern lineage giving rise to the Khama, and a northern lineage giving rise to the Kanki in the west and the Kongoni, Korkay and Tora in the east.

Caption: that’s a lot of lineages. The hartebeest phylogeny published by Flagstad et al. (2001); wildebeest were used as the outgroup. From Flagstad et al. (2001).

DNA and fossil evidence also indicates that the extant alcelaphines (hartebeest, wildebeest, topi and kin) became extinct across most of their Pleistocene range and survived into the Holocene in just a few refugia. For hartebeest, two of these were north of the equator and one was south of it (Arctander et al. 1999, Flagstad et al. 2001). It’s well known that alcelaphines are a very young clade (perhaps less than five million years old), and that, within their short history, they diversified rapidly. Data shows that their diversification events match key climatic changes, and in fact their evolution inspired Elisabeth Vrba to come up with the ‘turnover pulse’ hypothesis, this being that major climatic events cause rapid and simultaneous evolutionary turnover in distinct but similarly affected lineages.

For more on pecoran artiodactyls at TetZoo, see…

Stuffed megamammal week, day 2: Eland, April 2009

The many magnificent subspecies of Argali, February 2011

The ‘Great bubalus’ in ancient African rock art, April 2011

The monster sheep that wasn’t, and other tales of African Bovini, May 2011

Reasons for really liking wildebeest, February 2014

The Pronghorn Antelope: Designed by Committee, March 2014

Release the Fossil Pronghorns!!, November 2021

Suddenly -- Duikers!, June 2022

This blog benefits from your support. Thank you to those who help via patreon!

Refs – -

Arctander, P., Johansen, C. & Coutellec-Vreto, M. A. 1999. Phylogeography of three closely related African bovids (tribe Alcelaphini). Molecular Biology and Evolution 16, 1724-1739.

Flagstad, Ø., Olsaker, I. & Røed, K. H. 2004. The use of heterologous primers for analysing microsatellite variation in Hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus. Hereditas 130, 337-340.

Flagstad, Ø., Syvertsen, P. O., Stenseth, N. C. & Jakobsen, K. S. 2001. Environmental change and rates of evolution: the phylogeographic pattern within the hartebeest complex as related to climatic variation. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 268, 667-677.

Kingdon, J. 1997. The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego.

Ruxton, A. E. & Schwarz, E. 1929. On hybrid hartebeests and on the distribution of the Alcelaphus buselaphus group. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 38, 567-583.