I have no idea whether I’m known for being a specialist on anything. But of the several zoological subject areas I publish on, among my favourite and most revisited is the dinosaurs of the English Wealden, and in particular the theropods (that is, the predatory dinosaurs) of the English Wealden.

Caption: at left, a Wessex Formation scene, depicting Eotyrannus, a compsognathid (at lower right), a pachycephalosaurian Yaverlandia in the middle distance, and the titanosauriform ‘Angloposeidon’. I need to do some new Wealden dinosaur artwork. At right: a younger, slimmer version of this blog’s author, holding the holotype claw of Baryonyx walkeri in 2001 or thereabouts. Images: Darren Naish.

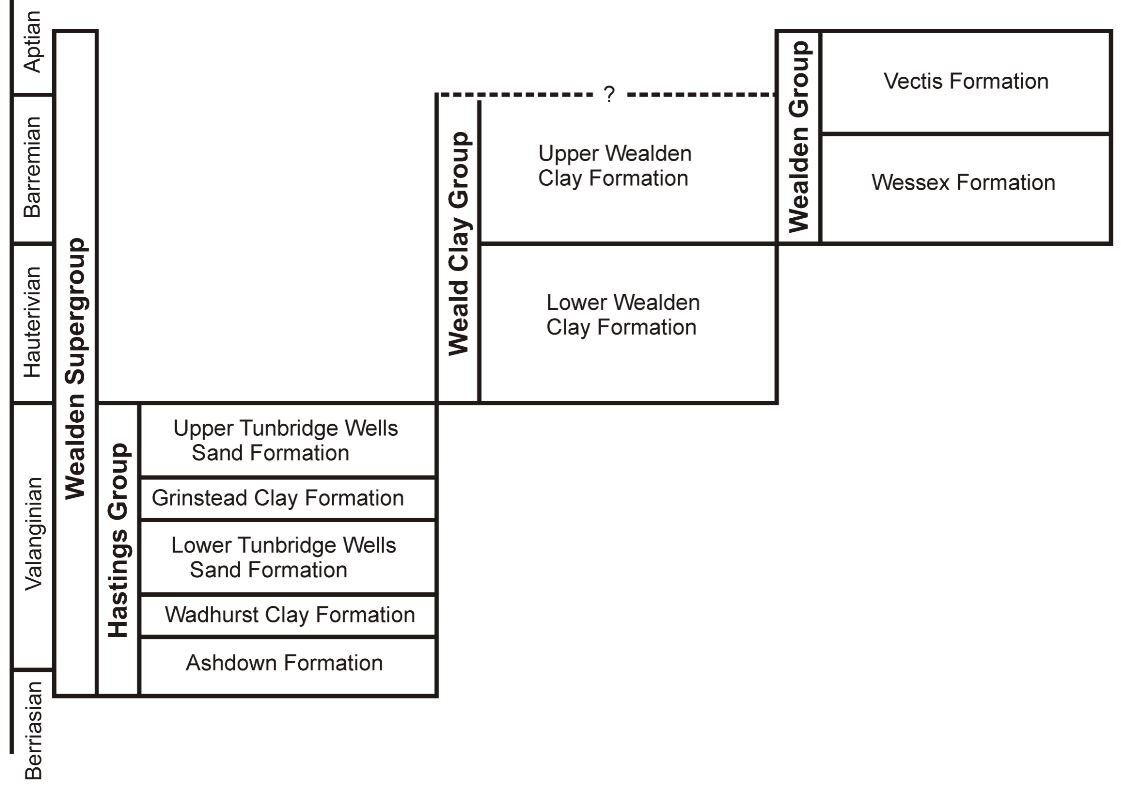

What is the Wealden? It’s a Lower Cretaceous succession – formed of sandstones, siltstones, mudstones, limestones and clays – which was deposited during the Early Cretaceous, its oldest layers being from the Berriasian (and thus about 143 million years old) and its youngest from the early Aptian (and thus about 124 million years old). The sedimentology, subdivisions and terminology of the Wealden are complicated, but all you need to know here is that the whole lot is termed the Wealden Supergroup, that it has an old section called the Hastings Group and a younger section called the Weald Clay Group – both of which crop out on the English mainland – and that there’s also a young section called the Wealden Group that mostly crops out on the Isle of Wight. Finally, you also need to know that the Wealden Group includes the Wessex and Vectis formations. Yikes, even that brief summary was complicated, sorry.

Caption: simplified stratigraphic nomenclature of the Wealden Supergroup. Note that the Hastings Group is much older than the Weald Clay and Wealden groups. The vast majority of Wealden dinosaurs come from the Wessex Formation. Image: Naish (2010).

The really interesting thing about the Wealden is that it’s highly fossiliferous, yielding everything from pollen and diatoms to dinosaurs. Wealden dinosaurs have been hugely important to our evolving understanding of these animals, in part because some of the earliest discoveries – Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus and Hypsilophodon among them – come from the Wealden succession. Many Wealden dinosaurs have also been famously vexing, in part because they were discovered at a comparatively early stage in our knowledge, in part because their remains have been (and still are) highly incomplete, and in part because their historical taxonomy is a convoluted nightmare. Note also that the circa 20 million year duration of the Wealden means that its dinosaurs were not all contemporaries. Instead, they belonged to a series of distinct faunal assemblages. Within the last few decades, the Wealden has – focusing here on theropods alone – yielded the superstars Baryonyx, Neovenator and Eotyrannus, and its potential to give us really spectacular finds even today is affirmed by additional theropods that are yet to be published.

Caption: the Wessex Formation allosauroid Neovenator – here shown with some of its facial bones in partial x-ray – was covered here at TetZoo (ver 3) back in 2017. Our conclusions on the facial anatomy of this dinosaur (Barker et al. 2017) have since been challenged. Image: Darren Naish.

While I could say a whole lot more (I’ve co-authored a whole book on Wealden dinosaurs: Martill & Naish 2001), the point of the article here (and its follow-up, to be published later) is to provide a progress report of sorts on a few contentious or in-prep areas of Wealden theropod research. And I’ll admit right now that the topics I cover here are unashamedly based on my own research interests and projects, sorry. To work…

Caption: at left, Martill & Naish (2001) (cover art by Julian Hume). At right, Batten (2011), truly a must-have volume on Wealden palaeontology. Martill & Naish (2001) is now hard to get and only sold at ridiculous prices.

What are you, Yaverlandia? In 1923, Mr F. M.G. Abell discovered the partial skull roof of a fossil reptile at Yaverland on the Isle of Wight. Its thickened bone immediately led Watson (1930) to suggest that it might be from a pachycephalosaur. Fast forward now to the 1970s: Peter Galton – at the time, revising and redescribing all British ornithischians – took this idea and ran with it. He formally named the specimen Yaverlandia bitholus and argued that it was indeed a pachycephalosaur, the most archaic known (Galton 1971). This became the standard take on this dinosaur and the one I supported when writing Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight in 2001 (Naish & Martill 2001).

Caption: at top, the Yaverlandia holotype in (left) ventral and (right) dorsal view. Below, the source of shame. Images: Darren Naish.

During my PhD years I was inspired to think about Yaverlandia anew, mostly because Jim Kirkland and Robert Sullivan (busy at the time with pachycephalosaurs) were pushing the idea that Galton’s identification was very likely wrong. I borrowed the specimen, produced a redescription, had the specimen CT-scanned, and photographed it to death. And I discovered a bunch of new stuff, all of which convinced me that Yaverlandia was not a pachycephalosaur at all, but a theropod. This data formed a chapter of my PhD thesis and brief summaries of my conclusions have been made here and there, including at conferences and in Naish (2011).

Caption: life reconstructions of Yaverlandia are few and far between. This one (seeming to show the animal in a quadrupedal pose: note how the artist has hidden the hand, a classic case of trying to cover up a mistake) is from the fabled Orbis part-work magazine series. I think (but can’t confirm) that the artist was Jim Channel. Image: (c) Orbis.

But the full, detailed explanation of the theropod hypothesis hasn’t yet appeared, though I promise that it will eventually (it’s a work I’m co-authoring with Andrea Cau). As is so often the case with my academic projects, I haven’t been able to make time to finish it (insert reminder about all my academic research being unfunded and done in ‘spare time’: I am not employed in academia). I should also add that a second specimen of Yaverlandia is known and also awaits writing-up. That’s a study I’m doing with Steve Sweetman.

Caption: it’s well known in the theropod research community that the full description of this amazing fossil – the holotype of the Spanish ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus – was done back in the 1990s [UPDATE: nope, 2004], but hasn’t seen print for a bunch of reasons. Consequently, good information on the specimen isn’t (yet) available. Despite that, this photo has been widely shared online. I don’t know who to credit for it.

Are there ostrich dinosaurs in the Wealden or not? Back in the day, I was thrilled by the 1994 description of the remarkable multi-toothed ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus polyodon from the Barremian Calizas de La Huérguina Formation of Spain. Not just because it’s a neat dinosaur, but because the Calizas de La Huérguina Formation has a lot in common with the Wealden: the two share a list of amphibians, mammals, lizards, crocodyliforms and dinosaurs, this rendering it plausible or likely that Pelecanimimus (or a similar taxon) might await discovery in the Wealden too (Naish et al. 2001, Naish 2002). Predicting the presence of a given group in a given faunal assemblage is a cheap and easy thing to do, and you can award yourself points for prescience and smarts if you’re proved right (even though most people will ignore your prediction), and no-one cares or notices if you never are. So, I’m not looking for a Wealden cookie here. Whatever, “where are the Wealden ornithomimosaurs?” was a question on my mind for a while.

Caption: these drawings – produced for Dino Press magazine back in 2002 – look very dated now. They’re supposed to show those smaller theropod groups confirmed for the Wealden (at top) and predicted for the Wealden but still awaiting discovery (at bottom). Images: Darren Naish.

So, I was pretty happy when – in 2014 – Ronan Allain and colleagues announced their discovery of such creatures in the Wealden. They’d discovered a new theropod in the Lower Cretaceous of France (specifically, in the Hauterivian or Barremian of Angeac in Charente, southwestern France) and had used this as a ‘Rosetta Stone’ in the interpretation of other Lower Cretaceous European theropod fossils (Allain et al. 2014). Several Wealden theropods – Valdoraptor, the Calamosaurus tibiae and Thecocoelurus among them – were ornithomimosaurs according to this study (Allain et al. 2014).

Caption: in 2014, I superimposed an ornithomimid into the Wessex Formation scene you saw above… this effort was not meant to be entirely serious (and an ornithomimid is the wrong kind of ornithomimosaur anyway). Image: Darren Naish.

I was initially enthusiastic about this proposal and thought that the authors were likely right. But as more and more information has been released on the Angeac theropod, the less like an ornithomimosaur it seems. It looks, instead, like a noasaur. Furthermore, the assorted relevant Wealden remains aren’t as similar to the bones of the Angeac animal as initially argued (Mickey Mortimer pointed this out in an article of 2014). Proper evaluation of what’s going on here will have to wait until a full description of the Angeac theropod appears in print. But if the Angeac theropod is a noasaur, the possibility that it’s close to or congeneric with one or more Wealden theropods remains a likelihood: Thecocoelurus (named for a single cervical vertebra from the Wessex Formation) looks like a noasaur vertebra (Naish 2011)... though that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is (since it also looks like an oviraptorosaur or therizinosaur vertebra in some features).

Caption: Mickey produced this image for a 2014 article at The Theropod Database (here).

To bring this round full circle, we might still be missing those predicted Wealden ornithomimosaurs.

Are there other Wealden tyrannosauroids besides Eotyrannus? Loooong-time readers of my stuff – I mean, those who’ve been visiting TetZoo since 2006 – might remember my suggestion from way back that some of the smaller theropod specimens from the Wealden are sufficiently similar to tyrannosauroids from the Lower Cretaceous of China to perhaps be additional small-bodied members of this group. I’m talking about Calamosaurus foxi (named for two cervical vertebrae), Aristosuchus pusillus (named for a partial pelvis and sacrum) and a few additional bits and pieces, including the so-called Calamosaurus tibiae (note the plural there). If these remains do belong to tyrannosauroids, they’re from taxa distinct from Eotyrannus (which everyone agrees is a tyrannosauroid).

Caption: the phylogeny I generated for my PhD thesis led me to think that Mirischia might be a tyrannosauroid… in which case Aristosuchus might also be a tyrannosauroid. This isn’t supported, however, in the in-prep Eotyrannus study I’ve co-authored with Andrea Cau. Image: Darren Naish.

I formally suggested a tyrannosauroid identity for Calamosaurus in a 2011 review of Wealden theropods (Naish 2011) but opted to keep Aristosuchus as a compsognathid on account of its similarity with Mirischia from Brazil. However, Mirischia also looks tyrannosauroid-like in some details (it has an anterodorsal concavity on the ilium) and I’ve sometimes wondered if it might also be a member of this clade. Recent results, however, do not support this possibility.

Caption: Aristosuchus pusillus is known from a sacrum and its conjoined pubic bones, which possess a notably long, narrow pubic boot (shown in ventral view in the image at bottom right). At left, we see where these bones would fit within the animal (here portrayed as a corpse; the reconstruction is dated and was produced for a conference poster I presented in 1999). Images: Darren Naish, Owen (1876).

So… Calamosaurus, are you a tyrannosauroid or not? When you only have two cervical vertebrae to go on (plus some tibiae that may or may not from the same taxon), it’s about impossible to say, and you can’t resolve things until you have better material. Like, an associated skeleton.

Caption: at left, one of the two holotype Calamosaurus foxi vertebrae in multiple views (from Naish et al. 2001). The bone is about 40 mm long in total. At right, a schematic reconstruction showing the two vertebrae in place in the cervical column of a compsognathid- or tyrannosauroid-like coelurosaur (from Naish 2002). Scale bar = 50 mm.

On that note, long-time readers might also recall my mention of a fairly good, associated skeleton of what appears to be a small Wealden tyrannosauroid. But it’s in private hands. I’ve been told by a British palaeontologist that the specimen concerned won’t be available for “this generation” of dinosaur specialists and I should simply forget about it. That’s hard, really hard.

And that’s where we’ll stop now. A second part to this article will be published soon.

For previous TetZoo articles on Wealden theropods and other dinosaurs, see (linking here to wayback machine versions due to destruction or paywalling of everything at versions 2 and 3)…

Of Becklespinax and Valdoraptor, October 2007

The world’s most amazing sauropod, November 2007

Oh no, not another new Wealden theropod!, June 2009

Concavenator: an incredible allosauroid with a weird sail (or hump)... and proto-feathers?, September 2010

The Wealden Bible: English Wealden Fossils, 2011, November 2011

Ostrich dinosaurs invade Europe! Or do they?, June 2014 (every archived version of this article lacks the original illustrations, sorry)

Refs - -

Allain, R., Vullo, R., Le Loeuff, J. & Tournepiche, J.-F. 2014. European ornithomimosaurs (Dinosauria, Theropoda): an undetected record. Geologica Acta 12, 127-135.

Galton, P. M. 1971. A primitive dome-headed dinosaur (Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of England and the function of the dome of pachycephalosaurids. Journal of Paleontology 45, 40-47.

Naish. D. 2002. Thecocoelurians, calamosaurs and Europe’s largest sauropod: the latest on the Isle of Wight’s dinosaurs. Dino Press 7, 85-95.

Naish, D. 2010. Pneumaticity, the early years: Wealden Supergroup dinosaurs and the hypothesis of saurischian pneumaticity. In Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343, pp. 229-236.

Naish, D. 2011. Theropod dinosaurs. In Batten, D. J. (ed.) English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 526-559.

Naish, D., Hutt, S. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Saurischian dinosaurs 2: Theropods. In Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. (eds) Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 242-309.

Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Boneheads and horned dinosaurs. In Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. (eds) Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 133-146.

Owen, R. 1876. Monograph of the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations. Supplement 7. Crocodilia (Poikilopleuron), Dinosauria (Chondrosteosaurus). Palaeontographical Society Monograph 30, 1-7.

Watson, S. 1930. Cf. Proodon [sic]. Proceedings of the Isle of Wight Natural History and Archaeology Society 1930, 60-61.

![It’s well known in the theropod research community that the full description of this amazing fossil - the holotype of the Spanish ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus - was done back in the 1990s [UPDATE: nope, 2004], but hasn’t seen print for a bunch of r…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510be2c1e4b0b9ef3923f158/1585002681161-29JO3RG3SRL02I363HHH/Wealden-theropod-questions-Mar-2020-Pelecanimimus-holotype-skull-1274px-250kb-Mar-2020-Darren-Naish-Tetrapod-Zoology.JPG)