Time for some speculation about a hypothetical issue…

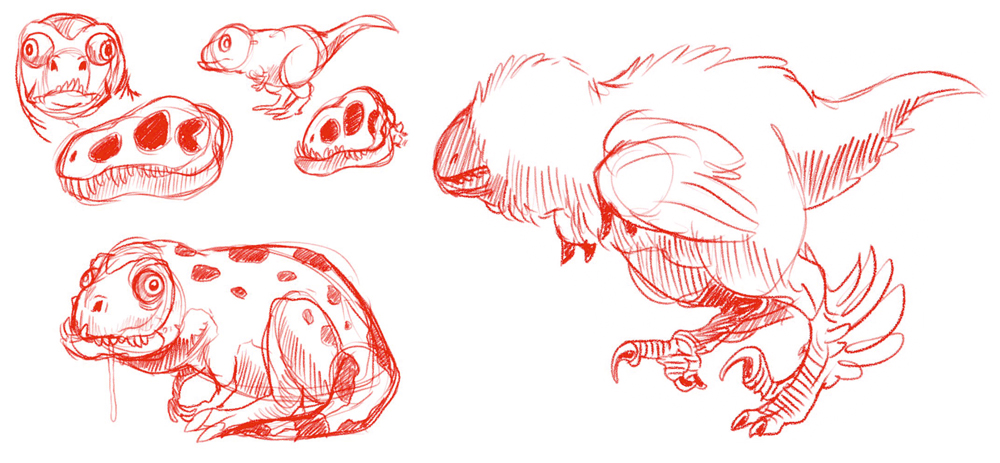

Caption: an ornithomimid being ridden at a riding school; a luxuriantly feathered, selectively bred dromaeosaurid. Images: James Robins (l), Ethan Kocak (r); used with permission.

Could we domesticate non-bird dinosaurs, supposing – hypothetically – that we lived in some alternate timeline? This might not seem like the sort of issue I readily tackle here at Tet Zoo (or… it might), but I’ve been inspired. My attention, you see, was drawn to an internet site where an expert attempted to answer the same question. Aaaand the answer they gave was pretty much useless, so here we are.

Caption: a friendly pet Parasaurolophus, as illustrated by Mike Skrepnick (and used with his permission) for a 'Would Dinosaurs Make Good Pets' project produced in conjunction with Dinosaur Provincial Park. Image: Mike Skrepnick.

Ever keen to give fair credit to those who’ve gone before me, I feel duty-bound to remind you that the issue of hypothetical (non-bird) dinosaur domestication has been covered at least a few times before, mostly in speculative fiction. During both the 1980s and early 2000s (Mash 2003), Robert Mash published his whimsical How to Keep Dinosaurs whereby non-bird dinosaurs as shown acting as pets, livestock, guards and so on in a world where the extinction event never happened. James Gurney's 1992 Dinotopia (and its sequels and spin-offs) features dinosaurs and other animals that - while not technically domesticated - are often featured performing tasks akin to those associated with domesticated animals today. And the 1990s Orbis children’s magazine Dinosaurs! included a well illustrated feature on imaginary dinosaur-human interaction, it being implied that at least some of the dinosaurs were domesticate*.

* ‘Domesticate’ as used throughout this article is not a typo for ‘domesticated’. It’s a noun used for a domesticated organism.

Caption: during the 1990s, British artist Jim Robins produced a whole set of illustrations depicting non-bird dinosaurs in modern, human-dominated scenes. With his permission, I reproduce several of them here. Image: James Robins.

Finally, an extremely odd book titled Who Lies Sleeping? – it’s predominantly concerned with the idea that Mesozoic dinosaurs might have evolved human-like intelligence and then caused their own premature extinction via nuclear annihilation or something – urges us to consider the possibility that the extravagant crests, horns and frills of Cretaceous ornithischians might provide compelling evidence of domestication by big-brained dinosaur overlords (Magee 1993). I see.

Caption: an industrial Parasaurolophus, from Magee (1993): "Did the hadrosaurs evolve breathing apparatus to protect themselves from atmospheric pollution", Magee asks. Ok. You might recognise the Parasaurolophus if you're familiar with the contents of Bakker's Dinosaur Heresies. Image: Magee (1993).

First things first: what is domestication? Domestication is the creation of a population of living things, distinct in some way from their wild ancestors, that are selectively bred by humans. The main function of domestication involves use of those living things for food, labour, companionship or ornamentation. As evidenced by the extraordinary number and variety of domestic plants and animals, it’s either that we’re really good at it or that it’s really easy once you’re smart enough to wilfully shape the evolution of other living things. Or both. Note that domestication is not simply the grabbing and taming of animals from the wild.

While – when thinking of animals – we typically associate domestication with mammals and birds, don’t forget that animals of virtually all major groups can be domesticated, in theory. Witness domestic insects (Chinese silk moth Bombyx mori and Honeybee Apis mellifera) and fish (Goldfish Carassius auratus, among others) (Zeuner 1964). An argument has been made that there aren’t, technically speaking, any domesticated squamates, turtles or amphibians, but a counter-argument is that we’re actually pretty close to such animals being in existence (look at – for example – the many captive morphs of bearded dragon, some of which lack scales and could not exist outside of human care) and there’s no reason why they couldn’t exist given sufficient selective breeding. Time is one of the key factors here. We could – potentially, perhaps – have giant stripy domestic Komodo dragons by now if only we’d started a selective breeding project a few centuries ago [UPDATE: as discussed in the comments, an argument can be made that the ancient Egyptians domesticated crocodylians].

Caption: today there are captive lizards - forms of the Central bearded dragon Pogona vitticeps - that are significantly novel relative to their wild ancestors. The weirdest is the Silkback or Silkie: a lizard that lacks scales. There's some debate, but these animals are pretty close to being considered 'domestic'. Image: CC0, Pixabay.

So – could non-bird dinosaurs be domesticated? The short answer is surely: yes, if we had to, or wanted to, and I say this given that humans have proven themselves capable of domesticating just about any organism given sufficient time and motivation, as noted above. That’s a ‘general’ “yes”, however, by which I mean that it refers to non-bird dinosaurs in the general sense of referring to these animals as a group, not in the specific sense of having any one species in mind. For comparison: we’ve domesticated mammals (given that there are sheep and cows and dogs and so on), but that doesn’t mean that we’ve domesticated lions or aye-ayes, to my knowledge, so far.

On that note, it’s rather harder to be confident about the hypothetical domestication of a given species – let’s say, for argument’s sake, Tyrannosaurus rex – given that said hypothetical domestication would be contingent on the biology, behaviour, geographical range, physiology and ecology of that species. T. rex could, for example, be prone to some particular disease that would make its living alongside humans impossible, it could prove truly intractable and just impossible to tame or maintain in a human-controlled environment, or there could be something specific about – say – its life as a juvenile or nestling or even the precise place in which it lives that might also prevent domestication.

Caption: Moose Alces alces (these are Alaskan moose) are often mentioned in discussions of domestication attempts. The commonest thing said is that they come with too much baggage to allow domestication -- but this simply might not be true at all. Image: Ryan Hagerty, in the public domain. Original at Pixnio.

These unknowns are very much hypothetical, obviously, but would surely apply to some species: there are numerous instances where extant animals have proved problematic in the way I imagine. It’s been said, for example, that American moose have been dificult to keep in captivity in Europe, the implication being that some sort of disease prevents their survival in the region (Geist 1999), and then there’s the whole list of animals that have thus far proved either impossible or, at the least, very, very difficult to breed in captivity, predominantly because they don’t seem to like the conditions we provide them with (famous examples include giant pandas, cheetahs and some cranes). Maybe these animals could surely be domesticated in time, but why bother when there are so many other species that don’t come with the same baggage.

Some dinosaurs would be easy to domesticate…. perhaps. It should also be noted that non-bird dinosaurs might actually be well suited for domestication, and not difficult to domesticate at all. The rapid generational turnover, large clutch sizes, and relatively rapid growth of many species (especially small and mid-sized ones) could all make selective breeding and human exploitation desirable and relatively easy, so long as we’re talking about a human effort that extends over decades or centuries, at least. Remember that some workers posit life cycles for non-bird dinosaur where even big species (say, the hadrosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum) were sexually mature at two years of age and had exceeded 1.5 tons by their third year (Woodward et al. 2015).

Caption: if dinosaurs like hadrosaurs (this graph shows Maiasaura) grew this quickly - we're talking about an animal that is well over 1000 kg within 2 years and capable of breeding by that time, and can be raised on a diet of easily obtained, cheap fodder and produces large clutches to boot - well, we have an animal that might be very desirable as a subject of domestication. Image: Woodward et al. (2015).

The ability of at least some herbivorous dinosaurs to successfully consume and digest material that might be considered low quality, cheap and easy to obtain – we’re talking conifer branches, green vegetation of just about any sort and even wood – would be a major score as goes our ability to maintain these animals as captives over generations.

And the very fact that these animals lay eggs would also be potentially advantageous in a world where dinosaur domestication is possible since it would theoretically be easier to steal babies and raise them in a controlled environment away from their parents. We just don’t know if non-bird dinosaurs exhibited the same sort of imprinting on parental figures that so many birds do, but if they did we again have a feature highly advantageous to human manipulation.

Working With Dinosaurs. When discussing the issues covered so far, I’ve mostly been thinking about domestication that might produce animals bred for meat or egg production, or for use in labour. But what about the maintenance and creation of species used as companions or hunting partners? Here we come to that issue so perennial in discussions of dinosaur biology: intelligence.

Caption: trained or restrained combat dromaeosaurs: a familiar part of the Jurassic Park universe long pre-dating the Jurassic World movies. This panel is from a 1994 comic published in the Dark Horse Jurassic Park 'Raptors Attack' storyline.

The intelligence – whatever we mean by that term – of non-bird dinosaurs is a subject of eternal debate and uncertainty, and it might be that we never have a good, confident handle on this issue. Intelligence is certainly a red herring when it comes to domestication as a whole. As in, it’s effectively irrelevant: if domestication involves selective breeding and the creation and maintenance of populations designed to be valuable to humans, intelligence has nothing to do with it.

Intelligence does, however, have a role to play if we’re talking about the use of domestic dinosaurs in hunting, herding or in performing other tasks that involve co-operation with a human or another animal or animals. Humans work with dogs in this way, of course, but we also have a long-standing and culturally important association with raptors (yeah, I told you it would be confusing if that word were co-opted for dromaeosaurs. It’s the word we use for hawks, eagles, falcons and such). Without going down the intelligence rabbit-hole too far, it’s conceivable that at least some non-bird theropods, and some ornithischians too, were on par with raptors, owls and other birds that can be used as hunting partners, though I happily admit that this is largely intuitive, difficult to demonstrate and isn’t all that well supported right now (e.g., Balanoff et al. 2013).

Caption: at least some bird-like non-bird maniraptorans were plausibly similar to, or approached, various modern birds in intelligence. Were they as smart as raptors and owls? ... neither of which are that smart compared to birds more 'properly' considered intelligent. At left, a trained Striated caracara Phalcoboenus australis extracts sticks in order to obtain a reward. At right, a hybrid Turkmenistan x Siberian eagle owl Bubo bubo trained to follow commands and perform in display flights. Neither birds shown here belong to domesticated species, but they're still relevant. Images: Darren Naish.

Let’s say that we could train dromaeosaurs, troodontids or oviraptorosaurs as hunting partners. There would have to be a cut-off as goes which species were considered manageable enough or safe enough to work with – above a certain size and firepower, a predatory theropod, or even a given omnivore or herbivore, could simply be too risky to be around for any length of time. More on this in a minute.

Caption: the effective function of a 'trained police dromaeosaur' as big as this one might not be plausible, but it sure is a cool image (even if the dromaeosaur is shown as unfeathered, tsk). Image: James Robins.

Matters of size. A non-trivial aspect of this discussion is dinosaur size. As per the discussion above, it would surely be plausible to raise and tame babies and youngsters of some, most or many dinosaur species that reach gargantuan size as adults. But what about when they reach that size whereby they become uncontrollable?

Elephants are tameable, as we all know, and can generally be controlled by a skilled person following an earlier phase in which the elephant is essentially forced to understand that it has no option but to obey the humans in charge (tangent: there is considerable debate as goes whether tamed elephants should be considered domesticated, since many – but not all – elephants used by people are not domestic as per the definition used earlier in this article). But every now and again a trained elephant snaps, refuses to obey the human giving it commands, and becomes a deadly force that ends in bloodshed, including that of the elephant. I’m not implying in any way that any of the dinosaurs applicable here could have been of intelligence or willpower or ingenuity or whatever on par with an elephant, but you do have to wonder if an angry, disgruntled or disobedient Triceratops or giant sauropod could be controlled or stopped should things go bad. So, what to do about dinosaurs that grow to be ten times – or more! – the size of an elephant?

Caption: super-sized sauropods could be bred to be fatter, more muscular and hence higher-yielding than their wild ancestors if domesticated and used for meat production, the result being chubbier, bulkier animals. But what would this mean for the controlling and handling of such massive, powerful animals? Could we even control them at all? Image: Ethan Kocak.

Solution 1: cull or release said animals when they reach whatever size has been found to be at the unmanageable threshold. Releasing them might be unworkable given that their familiarity with humans could then make them a nuisance or disruptive problem to whatever society was using them.

Solution 2: via selective breeding, produce dwarf forms that do not get to that threshold. Though… why bother when there are non-giant species of similar form?

Solution 3: invent and employ technology that forces the animal in question to comply, or prevents them from disobeying. We might speculate that devices like shock collars, neural transmitters or instant chemical suppressants would not act swiftly enough to stop any dinosaur giant from inflicting problematic damage… unless it were instantly fatal. I’m reminded here of the method used by Hasdrubal of the Carthaginian Republic – Hannibal’s brother – to deal with an armoured war elephant should it do an about-turn on the battlefield and start charging through the lines of its own side: supposedly, the elephant’s riders were armed with a mallet and spike, and would drive the spike into the elephant’s spine should it need to be disabled (Spinage 1994). I don’t know how easy this would be, but there we go. Solution 3 would surely involve practices rightly deemed unethical.

Caption: armoured war elephants have been used by several cultures. This image originally appeared in Friedrich Arnold Brokhaus's atlas, published sometime before 1850. Image: Karl Gröning; Elephants: A Cultural and Natural History.

I should also add that the emergency disabling or killing of a giant dinosaur would create all kinds of practical and logistic issues given the size of the carcass. The swift and efficient removal of a multi-ton carcass would be a necessity if the disobedient dinosaur in question succumbed in a settled area, else we could well be talking about a serious public health issue: there are the swarms of scavenging insects, enough fluidic runoff to influence local water sources, noxious smells not generally considered fun to be around by humans, and potentially the attraction of scavengers… maybe lots of them.

Domestication is ‘good’, domestication is ‘bad’. As is the case for some modern domesticate animals, becoming domesticated could be a short-term ‘wise move’ for the species concerned given human protection and propagation. Conversely, non-domesticate wild relatives of the species concerned would be at a disadvantage as their habitat was captured or managed for the domestic one, and perhaps as the risk of competition, hybridisation and aggression from said wild relatives would encourage humans to persecute and even destroy them. Exactly such a thing is said to have affected tarpans – wild relatives and near-ancestors of the domestic horse – given that tarpan stallions were apparently able to out-compete domestic stallions in mating battles and thus introduce non-desirable traits into the next generation.

A logical outcome of non-bird dinosaur domestication, then, might be ‘monocultures’ where a handful of species are super-abundant, the landscape has been changed to best suit the domestic species concerned, and wild relatives are rare, marginalised, or forced into extinction.

Caption: small theropods, and maybe other dinosaurs too, might make good pets, though they may prove incompatible with smaller pets of different species, as implied here. This is another of the illustrations produced by Jim Robins described above (and used here with permission). Image: James Robins.

That which might be possible. An over-riding pattern of domestication has been and is our ability to find variable anatomical traits in animals, and to induce, via often skilled selective breeding, the elaboration or modification of that trait, often at reasonable speed across the generations. I should add that this is the issue discussed and illustrated at length in Katrina van Grouw’s 2018 book Unnatural Selection (van Grouw 2018). We might not know anything particularly useful about potential intraspecific variation within non-bird dinosaur species, but we at least have some indication of what could be possible given the features that proved variable in their real world, natural evolved versions.

With that in mind, let’s speculate and have fun considering some of the things that might be possible in a world where non-bird dinosaurs have been domesticated, and where humans have become good at selectively breeding them. The showiness and elaborate ornamentation of ceratopsians and other ornithischians could mean that whichever species have been domesticated have been selected for ever more elaborate, ever showier structures.

Alternatively, the dangerous nature of horned and armoured ornithischians could encourage the development of unarmoured, less destructive, more benign forms that are positively plain and bland relative to their ancestors.

Caption: a bland, domesticated ceratopsid with reduced cranial structures relative to its wild ancestor. Image: Darren Naish.

Fighting dromaeosaurs, troodontids or small ceratopsians – equipped with more lethal armament and tougher hides and external coverings than their wild ancestors – could be developed in a society that did not prevent or make illegal the maintenance of such animals, a history that could lead to the creation of incredibly dangerous, near-uncontrollable strains or individuals. Maybe such animals could form the breeding stock of dinosaurs designed for urban pacification, crime-fighting and military application, though the last of these idea is now sadly and woefully unoriginal given the several appearances of trained or semi-trained ‘combat velociraptors’ in the Jurassic Park and Jurassic World franchises. Picture a trained, burly dromaeosaur with body and limb armour, prosthetic pseudoteeth, and a tight, perpetually reinforced bond with the lone human handler who has lived with it its whole life.

Caption: a girl and her ornithomimid. Greg Paul said of theropods in Predatory Dinosaurs of the World that "Their stiff, perhaps feathery bodies were not what one would care to have sleep at the foot of the bed" (Paul 1988, p. 19), but maybe he was wrong. This is another of Mike Skrepnick's illustrations from his 'Would Dinosaurs Make Good Pets' project. Image: Mike Skrepnick.

At the other end of the scale, the cute appeal of at least some non-bird dinosaurs – various of the short-faced maniraptorans and small ornithischians – could result in ubercute, cuddly, dwarf forms or super-showy ornamental forms with spangly, iridescent exteriors and hypertrophied tails. There might be a subculture whereby keepers of fancy maniraptorans have bred radically surreal, immaculately groomed and bejewelled creatures deliberately made to mimic objects of heraldry or fiction, like dragons, griffins or aliens from sci-fi stories.

Caption: I give you captively bred domestic theropods created by Ethan Kocak: a short-faced, miniature tyranno-pug, and a plush, poodle-like maniraptoran with luxuriant plumage. Image: Ethan Kocak. He's a New York Times bestselling artist, dontchaknow.

Here's to the future of domestic dinosaurs. My overall conclusion – I think it’s pretty obvious by now – is that non-bird dinosaurs of several, many or most sorts could indeed be domesticated, and might in fact be domesticated quite easily. We might maintain species of many sorts as beasts of burden or for food; predators and nimble omnivores and herbivores could perhaps be used in stock control or as partners in hunting; and those animals we might consider attractive or visually or vocally interesting might be bred, modified and managed as show animals or companions. It goes without saying that all of this is nothing more than an exercise in speculative fiction, and that none of it has any real relevance as goes our relationship with those animals we really do live alongside.

But wouldn’t it make a cool book?

Refs - -

Balanoff, A. M., Bever, G. S., Rowe, T. B. & Norell, M. A. 2013. Evolutionary origins of the avian brain. Nature 501, 93-96.

Geist, V. 1999. Deer of the World. Swan Hill Press, Shrewsbury.

Mash, R. 2003. How to Keep Dinosaurs. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

Paul, G. S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Spinage, C. A. 1994. Elephants. T & A D Poyser, London.

van Grouw, K. 2018. Unnatural Selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford.

Woodward, H. N., E. A., Freedman Fowler, Farlow, J. O. & Horner, J. R. 2015. Maiasaura, a model organism for extinct vertebrate population biology: a large sample statistical assessment of growth dynamics and survivorship. Paleobiology 41, 503-527.

Zeuner, F. E. 1964. A History of Domesticated Animals. Hutchinson of London, London.