Welcome to the second of my articles on birdwatching in Tajkistan in Central Asia….

Caption: a montage of passerines discussed in this article….

As you’ll know if you read the first article, I wasn’t in Tajikistan for bird-related reasons and in fact I only got to engage in opportunistic ‘fly-by’ birding. Nevertheless, I was thrilled with what I saw. In the previous article I covered the non-passerine species: various gallinaceous birds, waders, pigeons and raptors as well as the odd woodpecker, bee-eater and hoopoe. This time we get to the group that contains the bulk of extant avian diversity, the passerines or perching birds. And boy were there a lot of ‘difficult’ birds here, many of which have remained a mystery to me (in terms of identification).

Caption: an indication of what the scenery can be like in Tajikistan. This is the landscape around Lake Iskanderkul, a massive glacial lake on the northern side of the Fann Mountains. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: features of the Romit Valley in Tajikistan, a location where many of the birds discussed in these articles were seen. The valley featured wide, raging rivers (like the Kafinigan River shown here), and tall, jagged mountain peaks. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: another very scenic shot, this time in Saratag/Sarataq (both spellings seem to be in use), about 140 km north of Dushanbe, the capital. Note the mostly coniferous woodland across the slopes. Bears were here (as evidenced by fresh dung and conversations with locals). Image: Darren Naish.

For preamble and a short introduction on what Tajikistan is like and on what it’s like to look for birds there, be sure to check out the previous article. Alright, let’s get to it…

Shrikes, corvids and some surprising kin. We’ll start with corvoids. Several shrike species occur in Tajikistan, some of which only occur in the east and not here in Europe. I had good views of Long-tailed shrikes Lanius schach [UPDATE: this article previously had the species identified as Red-backed shrike L. collurio, a species I’ve seen before in eastern Europe], and what’s either Isabelline shrike L. isabellinus or Turkestan shrike L. phoenicuroides. The Long-tailed shrike is (in males, anyway) a very attractive, boldly marked bird with a reddish-brown back and light grey head. The other shrike is about impossible to pin down since both female and juvenile male Isabelline and Turkestan shrikes are sandy-brown with a less distinct mask than those of most other shrikes. Big thanks to Tim Worfolk (see comments) for his help here. Shrikes are one of my favourite bird groups, but so far I’ve only seen a handful of species. I spoke previously about them in this article on birdwatching in China.

Caption: I had bad luck in my efforts to photograph shrikes, buuuut then… I had bad luck in photographing just about all of the birds. Two Long-tailed shrikes are visible in this photo, I hope. Long-tailed shrikes occur widely across Asia and also occur in Australasia. Numerous subspecies have been named. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: more shrikes. The Long-tailed shrike photo at left isn’t great, but at least you can clearly see the grey head, black mask and pinkish sides. At right, an Isabelline or Turkestan shrike seen in shrubby vegetation close to a river. Images: Darren Naish.

Corvids are not especially diverse in Tajikistan. There are no exotic jays or magpies, nor any of those unusual crows with white head markings or massively overbuilt bills. Carrion crows Corvus corone were seen on numerous occasions at many rural (and not urban) places, but it was obvious immediately that they were distinct from those I know from Europe.

Caption: Carrion crows were seen in flocks of 10-15 on more than one occasion, implying that these Central Asian populations might be more social than the European ones. It should also be obvious that these crows are more slender and lightly built than western forms of this species. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Carrion crow seen flying overhead. I like the asymmetrical nature of the primary feather damage. It may or may not mean something (like handedness). Image: Darren Naish.

I had the impression that they were slimmer, shallower in the neck and with a proportionally longer, pointier bill than the Carrion crows I know here in the UK. Perhaps this is consistent with the view that these Asian birds represent the subspecies C. c. orientalis, the Eastern carrion crow. This occurs from Iran in the west to Japan in the east and is larger on average than the nominate form. That’s interesting, because my first (incorrect) impression on seeing these Tajik birds was that they were ravens. On that note, I was surprised to never once see ravens of any sort.

Magpies were seen on regular occasion, mostly in rural locations but also at roadside restaurants and parking areas. Recent studies show that the magpies previously lumped together in Pica pica have a phylogenetic structure that warrants the recognition of several species within Eurasia, in part because the American species (which have always been regarded as distinct species) are surrounded by Eurasian lineages. Magpies in Tajikistan belong to the bactriana subspecies, which groups with European and west Asian magpies in molecular studies (Song et al. 2018). This means that they should stay within P. pica, which makes sense as the Tajik birds I saw looked like European ones.

Caption: Tajik magpies. The bird at left – photographed in a carpark in the Fann Mountains – was missing some head feathers and hence not great in appearance. At right, a different bird, this time in Saratok. Images: Darren Naish.

A big surprise was the Indian paradise flycatcher Terpsiphone paradisi, a bird you might associate more with tropical south-east Asia than the very different habitats of Central Asia. Certainly I did. I have to mention upfront that the species I’m dealing with is one of three formerly lumped together as the ‘Asian paradise flycatcher’ (the others are the Chinese or Amur paradise flycatcher T. incei and the Oriental or Blyth’s paradise flycatcher T. affnis), and this – obviously – is the name used for the species in Ayé et al. (2012) and most other sources on Tajik birds.

Caption: Indian paradise flycatcher, a most handsome bird. Males and females are alike in possessing head crests, but males also have white primaries and very long central tail feathers. This is a female, and she belongs to the rufous form: there’s a white one where all the feathers are white excepting those on the head, neck and wing tips. Images: Darren Naish.

Also worth mentioning upfront is that Terpsiphone isn’t a ‘flycatcher’ in the way that most of us imagine this term: it’s not a member of the muscicapoid clade that includes conventional Old World flycatchers, but is a monarchid and thus part of Corvoidea. Within Corvoidea, monarchids are close to shrikes and corvids (Jønsson et al. 2016). They’re a widespread group with a complex phylogeographical history that involves tropical Asia, Africa, eastern Asia and the islands surrounding all of these places (Fabre et al. 2012).

Caption: action take-off shots of the same bird shown above. What these photos reinforce, partly at least, is that birds leap or fall into flight when launching from perches. They don’t start flapping and then take off. Images: Darren Naish.

A big surprise about this species is how agile it is in the arboreal environment. It doesn’t just perch on horizontal branches and sally back and forth, as you might predict for a bird with ‘flycatcher’ in its name. It clings to vertical trunks while probing the bark and will also move along a branch with its long axis parallel to that of the branch. A dark-headed, brown bird behaving in this way was identified by a member of our team as a woodpecker – meaning that we had a mystery bird on our hands – until we worked this out.

Caption: not a great photo, but an interesting one because it shows how paradise flycatchers are good at clinging and climbing about on trunks in woodpecker-like fashion. Image: Darren Naish.

Finally on corvoids, I saw a golden oriole in the same orchard at Hakimi where I got the woodpecker photos (see the previous article). As is typical for golden orioles, it was elusive and flew very quickly when eventually emerging from the foliage, so no photos. Two golden oriole species – the Indian Oriolus kundoo and European O. oriolus – occur across Central Asia but it looks like the latter is absent from Tajikistan. That matches what I saw, since the Tajik bird (a male) was very bright yellow with comparatively little black on its face.

We now move to the remaining passerines, the enormous, complex group technically termed Passerides.

Tits, or titmice if you’re that way inclined. Tits (Paridae) are an unusual group that were formerly regarded as not belonging to any of the major clades within Passerides. The most recent molecular studies show that they’re most likely an early-diverging group within Sylviida. A large tit, seen at close range in an orchard, was superficially similar to the Eurasian Great tit Parus major but grey on its shoulders and mantle and white on its sides and belly, rather than olive greenish dorsally and yellow ventrally. It can only have been one of ‘bokharensis group’ within the Great tit: a group of central and east Asian subspecies that were previously grouped together as the ‘Turkestan tit’. Some authors do still regard this as a distinct species (P. bokharensis).

Caption: a Tajik great tit, photographed foraging on a tree in an orchard, sometimes reaching under bark with its bill. This is obviously one of the grey ‘Turkestan tit’ subspecies, very distinct from the great tits of the west. Images: Darren Naish.

A few other species were far less familiar. A small tit with a boldly marked, black and white head, tall feather crest, yellowish nape and reddish vent area was seen on a few occasions in the Romit Valley. This is the Rufous-naped tit Periparus rufonuchalis, a widespread species that occurs from India north and east to China. The Periparus species – the best known is the Coal tit P. ater – are exclusive to Eurasia and northern Africa and a feature I now associate with species in the genus is a relatively long, slightly downcurved bill. That’s different from the shorter, more conical bill of tits like the Cyanistes species. And having mentioned the Cyanistes species….

Caption: a comparatively long-billed tit with a tall head crest, a reddish vent area and a lack of pale spots on its coverts. It can only be a Rufous-naped tit. Image: Darren Naish.

These very odd, mostly white and grey, yellow-breasted tits are Azure tits C. cyanus, a variable and polytypic, mostly Asian species that looks like a washed-out Blue tit. The two hybridize in western Russia and the resulting animal is known as Pleske’s tit. It was formerly regarded as a distinct species. Actually, the yellow-breasted form of the Azure tit I saw in Tajikistan is a distinct, Central Asian population that’s regarded as a distinct subspecies C. c. flavipectus by some authors, and as a species (the Yellow-breasted tit C. flavipectus) by others.

Caption: all my initial sightings of Azure tits (seen at Saratag in the Fann Mountains) involved the birds being seen in near-total silhouette, a classic example of the sort of bad luck that happens when you try and photograph birds. The only photos I got that don’t involve the birds being silhouetted are instead out of focus, like the example on the right. Images: Darren Naish.

Swallows and martins. Hirundines – swallows and martins – are a distinct lineage within Sylviida too. Individuals belonging to a few species were seen in the Romit Valley, but I never got any good looks nor any good photos. A smallish, light brown species seen flying over rivers was, I presume, Sand martin Riparia riparia, but Pale martin R. diluta, is also possible. The reddish throat, dark dorsal colour and long tail streamers of a second species made me think that it was Barn swallow Hirundo rustica.

Caption: terrible photos of small, fast-moving, brown hirundines. I’ve assumed that these are sand martins, but what’s with that white area on the tail? I remain confused. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: hirundines of, I think, two different species. The bird in flight at left is a Sand martin like those shown above, but the perched one at right is dark dorsally and has a dark, V-shaped area on its breast. These features mean that it has to be Barn swallow. Image: Darren Naish.

Warblers. Ok, I need to talk about warblers. Because boy did I see a lot of warblers. They fell into three groups: leaf warblers, acro warblers, and sylviid warblers. As covered on Tet Zoo before (see this article from February 2022), Old World warblers are part of Sylviida (formerly Sylvioidea) – the great passerine group that includes babblers, bulbuls, white-eyes, cisticolas and so on – and those groups we call ‘warblers’ aren’t close relatives (e.g., Oliveros et al. 2019).

Because I know you all love being reminded about the basic structure of the passerine family tree, here’s a reminder of the basic structure of the passerine family tree (albeit sticking only with Passerides), modified since the last time it appeared here…

Caption: a more elaborate version of the warbler-flycatcher-sparrow section of passerine phylogeny than we’ve seen here before, using the ‘up-ranked’ taxonomy used by Cracraft et al. (2004) and then modified by Oliveros et al. (2019). The clade we’re seeing here is now termed Passerides (whereas before it was Passerida), which means that the clades previously termed Sylvioidea, Muscicapoidea and Passeroidea are now up-ranked to Sylviida, Muscicapida and Passerida. These illustrations and the cladogram itself are part of my in-prep textbook project, which will one day be finished, I promise. Support it – and other projects – here. Image: Darren Naish.

Leaf warblers, or phylloscopids, are a mostly greenish, slender-billed group, often bearing a prominent supercilium (a pale eyebrow stripe). The numerous species are often difficult to tell apart and experts use song and specifics of wing feather length to differentiate them, features that can’t be applied to fleeting observations of live birds seen at distance. The leaf warbler you see here was perching on boulders and branches adjacent to the Kafinigan River in the Romit Valley. It has a yellowish supercilium, olive green mantle, a pale ‘covert bar’, light green secondaries, darker primaries, and legs that have pinkish and yellowish tones. It’s not long-billed and looks (on the basis of eye size and proportions) ‘mid-sized’ within the group. The species that seems to be the best match is the Greenish warbler Phylloscopus trochiloides, and that would make sense as this is one of the most widespread and common leaf warblers of the region. Other identifications are possible; let me know what you think if you know leaf warblers!

Caption: a mid-sized, fairly green leaf warbler, seen in the Romit Valley, that was moderately co-operative. I think it’s a Greenish warbler. Image: Darren Naish.

Here's another warbler, and this time it’s not a leaf warbler. The profile of its head and tendency to adopt a ‘skulking’ posture made me think that it might be an acro: an Acrocephalus warbler, the group that includes reed warblers. It’s brown, greyish ventrally, has a poorly defined supercilium (with some yellow just above the eye), a dark stripe through the middle of the eye, and a pale area adjacent to the wrist. The yellowish tint to the throat and belly is due to reflection from the adjacent leaves, I think. It’s also long-billed and has greyish legs.

Caption: a possible acro warbler that’s possibly a Blyth’s reed warbler. In this image, the bird is in a low, ‘skulking’ pose, with the feathers on its head depressed close to the skull. However, look at the other photo below to appreciate the different profile the bird has when not doing this. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: the exact same bird shown in the photo above, this time with a more erect pose and raised head feathers. Small birds often reflect the colour of nearby foliage on their pale parts meaning that they can look darker or lighter than they do in the hand, or in the field guide. Image: Darren Naish.

This description is most consistent with two species that occur in the region – Paddyfield warbler A. agricola and Blyth’s reed warbler A. dumetorum – and, of the two, Paddyfield warbler is my preferred identification because it’s a confirmed denizen of Tajikistan (Blyth’s reed warbler presence in Tajikistan is marked with question marks by Ayé et al. (2012)) and because it has a deeper supercilium than Blyth’s reed warbler, as does the bird I saw. Again, I could be wrong and I welcome alternative suggestions. UPDATE: following comments (see below), I’ve changed this and am now preferring the Blyth’s reed warbler suggestion.

A second, bigger acro was seen at Saratok, in the Fann Mountains north of Dushanbe. My only photos are fuzzy. This bird was warm brown dorsally, greyish ventrally, had a tall, dark forehead, a thin yellowish supercilium that extended a short distance behind the eye, short primary projection, and pinkish legs. Several possible identifications exist for this one, with Blyth’s reed warbler again on the list in addition to – outside bet – the poorly known Large-billed reed warbler A. orinus, which is present in Tajikistan but not well recorded there. I keep coming back to the possibility that it might be a Blunt-winged warbler A. concinens, since it looks so right. According to eBird, this species is confirmed for western Tajikistan, so this isn’t impossible. But maybe it’s just a Eurasian reed warbler A. scirpaceus in especially good light (they normally look duller brown and darker at the wingtips). Thoughts appreciated.

Caption: blurry photos of a warm brown warbler that has a tall forehead, yellowish supercilium and short wings. Am I right in thinking that this is an Acrocephalus warbler, and – le shock – is it a Blunt-winged warbler? Images: Darren Naish.

Finally, what about sylviids? I saw these on numerous occasions, both as singletons and in small groups of 2-3, and assumed I was seeing Ménétriés’s warbler Sylvia mystacea or a close relative. But no: the birds I photographed were relatively large, entirely white ventrally, and with a sharp line demarcating the white submoustachial area from the dark grey ear coverts. These features mean that they’re most likely Eastern orphean warbler Curruca crassirostris, a species that occurs from the Balkans east to eastern Kazakhstan and eastern India. I saw these low in the Karatag Valley as well as near Lake Timur Dara (higher in the valley).

Caption: a montage showing what I think are Eastern orphean warblers. The ‘orphean’ in the name (there’s a Western orphean warbler C. hortensis too) is a reference to Orpheus of Greek mythology, the musician, poet and singer. I presume the name is a reference to the singing of these birds. Images: Darren Naish.

Caption: more Eastern orphean warblers. The individuals with light grey heads shown here must be female, but the bird on the right – with the very dark head – would appear to be a male. Images: Darren Naish.

Thrushes, Old World flycatchers, and starlings. I saw two thrushes: Mistle thrush Turdus viscivorus (no photos) and Eurasian blackbirds T. merula. The latter were seen on numerous occasions, though the only bird I got useable photos of was in a shabby state. I also had the best views I’ve ever had of Common nightingale Luscinia megarhynchos. This bird was foraging on ground adjacent to an orchard and often cocked its tail.

Caption: female Eurasian blackbird, photographed foraging in a vegetable garden. The feather loss on the head might be due to disease. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: I’ve never had especially good views of nightingales before. This bird, photographed adjacent to a gardened shrine in the village of Hakimi, was especially co-operative in its posing. Images: Darren Naish.

Muscicapidae – the so-called Old World flycatcher family – is a large group that includes wheatears, chats, robins proper, nightingales, flycatchers proper (Muscicapa, of course, and kin) and birds with the word ‘thrush’ in their name, like rock thrushes. They are of course the core group within Muscicapoidea/Muscicapida, a clade that also includes waxwings and kin, kinglets, and creepers, wrens and kin (Certhioidea).

Caption: more Spotted flycatchers (others were shown in part 1). It might just be my bad colour vision (or the settings on my PC), but the one on the left has a pinkish hue to my eyes. Muscicapa striata was scientifically named by Simon Pallas in 1764 but included by him in Motacilla. The content of Muscicapa expanded after it was named by Mathurin Brisson in 1760 but recent studies have shown that its traditional version is polyphyletic, a consequence being that some species have been placed in other genera or given their own generic names. Images: Darren Naish.

As mentioned in the previous article, Spotted flycatchers Muscicapa striata were seen in some abundance, and the countryside was obviously ideal for their needs and preferences. I photographed as many individuals as I could, since it’s sometimes interesting to see variation (or the converse) within populations. I was aware that a second, similar flycatcher species – the Rusty-tailed flycatcher Fidecula ruficauda – occurs in the region, and was hoping that I might see it. And as you can see from this photo: I did! Ayé et al. (2012) of course have this as a species of Muscicapa, but molecular studies published more recently show it to instead be part of Ficedula (Hooper et al. 2016). For a time there were suggestions that it should get its own genus (Ripleyia, later changed to Ripleyornis due to preoccupation by a fossil mollusc).

Caption: Rusty-tailed flycatcher in the Romit Valley, very helpfully displaying its key field sign. It’s partly migratory, the Central Asian populations moving to India for the winter. Images: Darren Naish.

Wheatears of several species live in Tajikistan. One species was encountered in rock-strewn fields in heavily grazed parts of the Romit Valley. Its long primary projection, white rump and white sides to the proximal two-thirds (or so) of the tail show that it was likely a Northern wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe, and not a male as they have light grey upperparts and a black mask. Incidentally, the word ‘wheatear’ originated as a corruption of ‘white-arse’, this being a reference to the white rump of this species. UPDATE: thanks to a suggestion from Simon Woolley, I’m changing this from Northern wheatear to Pied wheatear O. pleschanka on account of its higher contrast, darker plumage.

Caption: at left, female Pied wheatear in a boulder-strewn field. I don’t think that this is an especially controversial suggested identification. At right, what might be a Variable wheatear. If that identification is correct, this has to be the black-belled opistholeuca subspecies. Images: Darren Naish.

What I think was a second wheatear species – the mostly black Variable wheatear O. picata – was seen on boulders near the Kafinigan River. This species is really, err, variable and there are white-capped, white-bellied and white-rumped forms as well as populations where all of those things are absent. As you can see, the one I saw (assuming it was a Variable wheatear) was black apart from a white base and sides to the tail. This makes it the ‘black-bellied’ O. picata opistholeuca, and the good news is that this form is said to belong to northern Afghanistan and at least part of Tajikistan (Ayé et al. 2012). However, read on…

What might have been a third wheatear – though I’m even less confident about this one – was seen in an area of small fruit trees in the Karatag Valley. The bird was chat-like in form, with an off-white breast, buff flanks, belly, undertail and rump, dark wings and tail, and grey-brown dorsal plumage. I thought at the time that this might be a female Pied wheatear O. pleschanka, though most populations of this bird have a dark throat. However, the ‘vittata’ form – which might occur in Tajikistan and is of unresolved taxonomic status – has a white throat. I don’t think that this identification is right though. Any better ideas?

Caption: at left, a chat-like bird from the Karatag Valley that might be a female Pied wheatear. If so, it must be the white-throated ‘vittata’ form. At right, a female redstart, perhaps a Black redstart. Images: Darren Naish.

A scruffy looking, probably female redstart was seen in the Romit Valley. I think it’s a Black redstart Phoenicurus ochruros in view of the pale streaking on the head. Eversmann’s redstart P. erythronotus occurs in Tajikistan but only as a winter visitor, and it has obvious pale borders to its coverts.

Finally on chats and kin, what I think was Plumbeous water redstart P. fuliginosus was seen perched on rocks in the Kafinigan River. Suspiciously, this bird was only several metres away from the ‘wheatears’ suggested above to be Variable wheatear, so now I wonder if my possible ‘Variable wheatears’ were additional Plumbeous water redstarts. Sitting on boulders next to a river is not a very wheatear-like thing to do, after all.

Caption: possible Plumbeous water redstart. If correct, it must be a female since males are blue with a red tail. The species was formerly placed in its own genus (Rhyacornis) but post-2010 molecular studies have found it to belong to the redstart genus Phoenicurus. Image: Darren Naish.

I mentioned in the previous article that Common or Indian mynas Acridotheres tristis were among the most frequently seen of Tajikistan’s birds. This species occurs from Iran all the way to peninsula south-east Asia, but it’s been introduced to numerous other places where it’s doing quite well, including Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, various islands in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, and parts of Canada (!) and of course Florida. Given how adaptable the species is, it certainly has the potential to out-compete natives, so this spread is a source of concern.

Acridotheres is a starling (Sturnidae). Various different affinities have been suggested for starlings in the past, among the most popular being that they’re corvoids or close to icterids and kin. Molecular data shows that they’re part of Muscicapida, and in fact close to thrushes and Old World flycatchers.

Caption: Common mynas were seen regularly in gardens, in fields with livestock, and in villages. White patches on the dorsal surfaces of the wings are very prominent in flight. Image: Darren Naish.

Dippers. Unsurprisingly for a mountainous nation with abundant, fast-flowing streams and rivers, Tajikistan has dippers, a muscicapoid group also close to thrushes and Old World flycatchers.

As you’ll know if you keep up with technical publications on avian evolution and morphology, that old claim about dippers lacking any and all specializations for aquatic life is not at all accurate. Smith et al. (2022) looked at all aspects of dipper anatomy in the interests of comparing them to other wing-propelled diving birds and reported diving adaptations in the nostrils, plumage, musculature and much else. Dippers do have diving adaptations, but these are weakly expressed relative to those of other diving birds, perhaps because they’re relative newcomers to the aquatic realm (Smith et al. 2022), or perhaps because they’re ecologically distinct in doing a form of shallow-water, near-surface foraging different from that of other diving birds. It should also be added that the ‘no aquatic specializations’ claim mostly related to skeletal anatomy anyway and – as Steve Ormerod has reminded me – it’s long been known that dippers have numerous soft-tissue adaptations related to aquatic life, including in their uropygial gland, feathers, eyes, nostrils and overall proportions.

Caption: I saw White-throated dippers at close range on several occasions, typically as they were flying quickly up or down the Karatag River. The only co-operative ones, like this one, were observed at great distance. Image: Darren Naish.

Two species can be found in Tajikistan: the White-throated dipper Cinclus cinclus (which I know well from Europe) and the Brown dipper C. pallasii, and I was most excited about potentially seeing the latter. I’m pleased to say that I saw (and photographed) both, though a complication I was aware of is that there’s a dark brown form of the White-throated dipper (C. c. baicalensis) that lacks the white throat! However, it has a light brown neck and breast, whereas the Brown dipper is dark brown overall.

Caption: a Brown dipper foraging at the edge of a river. These birds are happy divers and bottom-walkers, but they also wade in fast-flowing water, as is obvious here. In the image at bottom left, the white nictitating membrane is obvious. Image: Darren Naish.

Wagtails. We now move to the final major clade within Passerides: Passeroidea/Passerida, the group that includes sparrows, finches, buntings, icterids and so on. And somewhere within this lot (surprisingly, close to sparrows and finches) are the wagtails and pipits, or motacillids.

Wagtails were seen frequently at streams and rivers during my trip, specifically Grey wagtail Motacilla cinerea and White wagtail M. alba. The white wagtails were of the ‘Masked’ subspecies M. a. personata, which is unusual in that the black throat and breast are continuous behind the eye with the black nape and cap. These two zones are separated by white in most other white wagtail forms… but not all: M. a. subpersonata of Morocco has this too, as does the very black M. a. alboides of China and the Himalayas (Alström et al. 2003).

Caption: the Grey wagtails of Tajikistan look essentially the same as those of Europe. It’s an especially long-tailed wagtail. Images: Darren Naish.

Caption: masked, personata-type White wagtails, seen at different Tajik locations (but always close to rivers or streams). Images: Darren Naish.

Finches. One of the birds that surprised me the most, of all the Tajik birds I saw, actually belonged to a species – or does it? – that I already know from home, namely the European goldfinch Carduelis carduelis. I knew that goldfinches were present in the Karatag Valley before I got to look at them properly, since I heard their distinctive ‘tinkling’ calls and saw them, at distance, flying to, and feeding from, thistle heads. But when I got to see them properly, up close, I was surprised, since they were really odd-looking, being pale, lacking the black crown and nape typical of European goldfinches, and with a long, extremely pointed bill.

Caption: the strangest goldfinches. These photos show the same individual, but the other goldfinches I saw were like this one in bill form: it’s normal for this population. Images: Darren Naish.

Ayé et al. (2012) informally term this the ‘Eastern goldfinch’, but the taxonomy is a bit confused as more than one subspecies might be involved here (C. c. paropanisi and C. c. subulata among them). Indeed, goldfinches are variable across their extensive range and around 14 subspecies are recognized by some authors, these falling into the mostly western carduelis group and the mostly eastern caniceps group. I wonder if the long, especially pointy bill on the birds I saw is an adaptation for plants specific to the region.

A group of finches seen foraging on the ground in an orchard confused me until I realized that I was seeing a strongly dimorphic species where females are grey-brown (and whiteish ventrally) but males have a bright red head, breast and rump. I think that this is Common rosefinch Carpodacus erythrinus, a widespread Eurasian cardueline finch that, in the west, appears to be increasing its range across Europe. In the east, some populations winter in the Asian tropics.

Caption: on a partly bare slope at the edge of an orchard, a group of what I think were rosefinches were watched foraging on the ground. The red heads, necks and breasts of the males are obvious. Image: Darren Naish.

Mystery ‘finches’. I also saw a few mystery finches that I haven’t been able to identify. In ‘finch 1’, the plumage is nondescript and a key feature is a deep, conical bill. Reddish legs were visible in ‘finch 2’, a Karatag Valley bird. Are these more rosefinches, or are they something else, like Trumpeter finch Bucanetes githagineus? That species is not confirmed for Tajikistan, its nearest population being in Uzbekistan [UPDATE: several suggested identifications have been made for this bird in the comments; I most like Alan’s suggestion that it might be Plain mountain finch Leucosticte nemoricola]. Perched above Snake Lake (which, yes, was named for the former abundance of snakes there) was ‘finch 3’, a reddish-and-black bird with a pink, slightly down-curved bill and pinkish legs, streaked breast, and black wing and tail feathers bordered by white. It was cardueline-like in shape and stance. I’m totally stumped by this one – any suggestions?

Caption: a miscellany of mystery finches, or finch-like passerines. I look forward to seeing suggested identifications. Images: Darren Naish.

A finch-like bird – I think it might be a bunting – was seen on an acacia-like tree in the Karatag Valley. The tail, secondaries, coverts and tertials are black lined prominently with yellowish-brown, a pale eye-ring is connected to a stripe that separates the crown from the ear coverts, and the legs are pale. I reckon this is a female Red-headed bunting Emberiza bruniceps, a common species that’s present throughout Tajikistan and the surrounding countries. Other suggestions welcome!

Caption: a bunting (or similar passeroid/passeridan) with brownish, streaked plumage across the head and neck and where the wing feathers are black and lined with yellow-white. I’m suggesting that these are female Red-headed bunting, a familiar and common species in Tajikistan and adjacent nations. But I could be wrong. Images: Darren Naish.

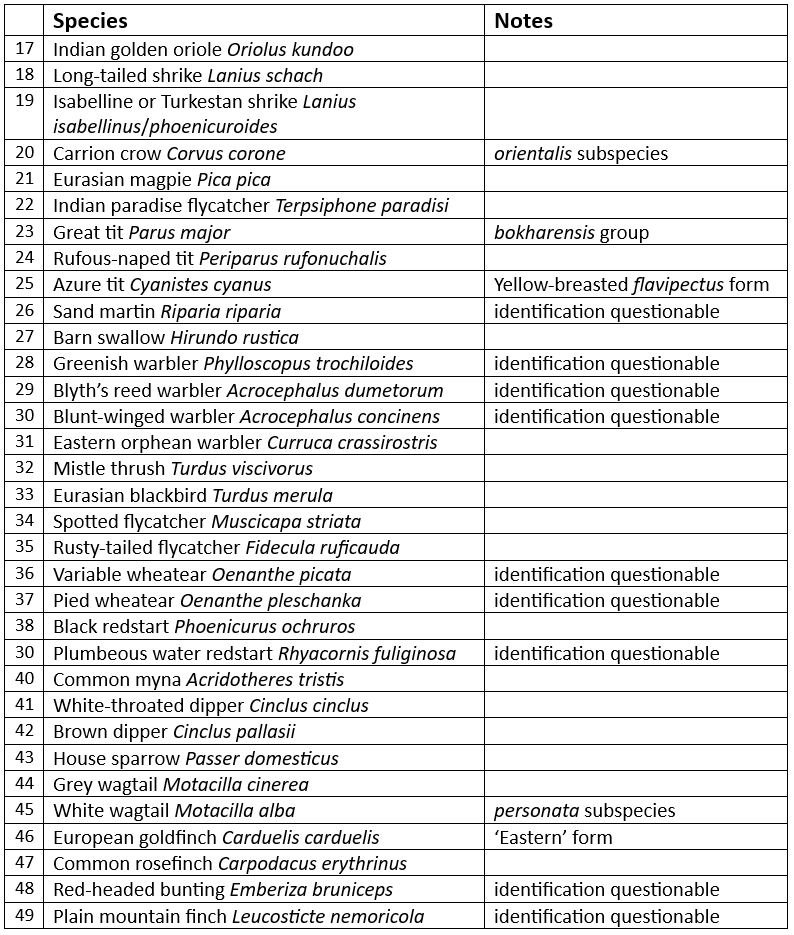

And that – finally – is where things come to an end. You’ll recall from the first article my table of non-passerines I saw. Here’s a table showing the passerines. The count continues from the non-passerines (where 16 species were observed)…

So that’s at least 49 species in total (32 of which are passerines). Not bad for casual, fly-by birdwatching, I think. It includes a few specialities of the region, some enigmas that are tough to identify at distance, and a huge amount that was entirely new to me. Of interest incidental here, perhaps, is the less than perfect nature of various of my photos. It should be obvious that I struggle to photograph fast-moving, small animals, for various reasons. I presume that everyone who photographs live animals has the same problem, it’s just that we don’t usually have any reason to see their bad or very bad photos. Aware of the substandard nature of many of my images, I provided the following poll, and look at the results….

So, you only have yourselves to blame.

And that is that. More discussion of what happened in Tajikistan is due to be covered here in time. For now, we move away to other topics. For previous articles on birdwatching in far-flung locations, see…

To the Sahara in quest of dinosaurs (living and extinct), December 2008

From Morocco, with larks, babblers, gazelles, owls and GIANT DINOSAUR BONES, December 2008

Birding in Brazil: a view from suburban Rio de Janeiro, June 2013

Birdwatching in Suburban China, May 2019

Suburban Birdwatching in Queensland, Australia, November 2019

Birdwatching in Oregon, June 2023

Birdwatching in Tajikistan, Part 1, October 2023

Refs - -

Alström, P., Mild, K. & Zetterström, B. 2003. Pipits and Wagtails of Europe, Asia and North America. Christopher Helm, London.

Ayé, R., Schweizer, M. & Roth, T. 2012. Birds of Central Asia. Christopher Helm, London.

Cracraft, J., Barker, F. K., Braun, M., Harshman, J., Dyke, G. J., Feinstein, J., Stanley, S., Cibois, A., Schikler, P., Beresford, P., García-Moreno, J., Sorenson, M. D., Yuri, T. & Mindell, D. P. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships among modern birds (Neornithes): towards an avian tree of life. In Cracraft, J. & Donoghue, M. (eds), Assembling the Tree of Life. Oxford University Press (Oxford), pp. 468-489.

Fabre, P.-H., Irestedt, M., Fjeldså, J., Bristol, R., Groombridge, J. J., Irham, M. & Jønsson, K. A. 2012. Dynamic colonization exchanges between continents and islands drive diversification in paradise-flycatchers (Terpsiphone, Monarchidae). Journal of Biogeography 39, 1900-1918.

Hooper, D. M., Olsson, U. & Alström, P. 2016. The Rusty-tailed flycatcher (Muscicapa ruficauda; Aves: Muscicapidae) is a member of the genus Ficedula. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 102, 56-61.

Jønsson, K. A., Fabre, P.-H., Kennedy, J. D., Holt, B. G., Borregaard, M. K. Rahbek, C. & Fjeldså, J. 2016. A supermatrix phylogeny of corvoid passerine birds (Aves: Corvides). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 94, 87-94.

Oliveros, C. H., Field, D. J. , Ksepka, D. T., Barker, F. K., Aleixo, A., Andersen, M. J., Alström, P., Benz, B. W., Braun, E. L., Braun, M. J., Bravo, G. A., Brumfield, R. T., Chesser, R. T., Claramunt, S., Cracraft, J., Cuervo, A. M., Derryberry, E. P., Glenn, T. C., Harvey, M. G., Hosner, P. A., Joseph, L., Kimball, R. T., Mack, A. L., Miskelly, C. M., Peterson, A. T., Robbins, M. B., Sheldon, F. H., Silveira, L. F., Smith, B. T., White, N. D., Moyle, R. G. & Faircloth, B. C. 2019. Earth history and the passerine superradiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 7916-7925.

Smith, N. A., Koeller, K. L., Clarke, J. A., Ksepka, D. T., Mitchell, J. S., Nabavizadeh, A., Ridgley, R. C. & Witmer, L. M. 2022. Convergent evolution in dippers (Aves, Cinclidae): the only wing‐propelled diving songbirds. The Anatomical Record 305, 1563-1591.

Song, G., Zhang, R., Alström, P., Irestedt, M., Cai, T., Qu, Y., Ericson, P. G. P., Fjeldså, J. & Lei, F. 2018. Complete taxon sampling of the avian genus Pica (magpies) reveals ancient relictual populations and synchronous Late-Pleistocene demographic expansion across the Northern Hemisphere. Journal of Avian Biology 49, e01612.