If you’ve heard of the Okapi Okapia johnstoni – and if you’re at all interested in the history of zoology – chances are high that you’ve heard the story of this animal’s scientific discovery…

Caption: taxiderm mount of the complete Okapi skin obtained by Sir Harry Johnston, photographed in the British Museum (Natural History). This specimen was key in the naming of Ray Lankester’s naming of the genus Okapia in 1901. Early depictions of the Okapi – including this one – gave them slimmer limbs than those present on the live animal. Image in public domain.

The story of the Okapi’s discovery has been told several times (Lankester 1902, Wendt 1959, Spinage 1968, Ley 1987, Heuvelmans 1995, Shuker 2012), most frequently in books written by authors especially interested in cryptozoology, the implication being that the relatively late scientific recognition of the Okapi might provide justification for the continuing existence of other large, mysterious terrestrial animals. My retelling here will be familiar to those who know the same books that I do. I have, however, augmented things with tangents and considerations that haven’t been included before, though I have to say that the novel stuff mostly appears in Part 2.

Caption: I’m lucky enough to have seen live Okapis on many occasions, though always in zoos of course. These males were photographed at Marwell Wildlife, UK. Images: Darren Naish.

As ever, we should make it clear that we’re talking here about European or scientific discovery, since the Okapi was known for sure to people of the Congo region.

On that note, the overwhelming take-home from the story of the Okapi’s discovery is that it goes hand-in-hand with colonial exploitation and the numerous suppressions of rebellions, administrative reorganisations and negotiations of land ownership that occurred throughout the so-called Scramble for Africa. It doesn’t take much digging to link at least some of the British and Belgian officials concerned to problematic events, all of which means that the story of European science in the Congo is ripe for reframing and a more accurate retelling. I apologise for any shortcomings in the text here.

Today, the area inhabited by the Okapi is within the Democratic Republic of the Congo (or DRC), previously (between 1971 and 2006) known as the Republic of Zaire, before that (between 1908 and 1964) termed Belgian Congo, and before that (between 1885 and 1908) known as Congo Free State. The proximity of the Okapi’s range to the extreme north-east border of DRC means that this area was sometimes within the borders of adjacent Uganda.

Caption: current range of the Okapi as depicted by the IUCN. It is entirely within DRC. From Mallon et al. (2015).

Europeans learn of the Atti. The first instance of European awareness of the Okapi* came in 1890 when author, soldier, journalist and colonial administrator Henry M. Stanley made fleeting reference to a forest ‘donkey’ in volume 2 of his Darkest Africa. The Wambutti people, said Stanley, knew it as the Atti. Actually, it’s not entirely clear that this was the word they had for the animal, and this might instead have been their word for ‘ass’ or ‘horse-type animal’. At some point, the alleged existence of this ‘Atti’ became known to explorer, author and colonial administrator Harry Johnston (made Sir Harry in 1896), though whether he learnt this from a meeting with Stanley or from reading Stanley’s book isn’t clear, since he claimed both sets of events at different times.

* Herodotus mentioned a ‘horned ass’ that inhabited the forests of Libya, and there have been suggestions that this might have been a reference to the Okapi. But it’s really not good enough to say that it was. Other claims of early European awareness of the Okapi have been made; we’ll get to them later.

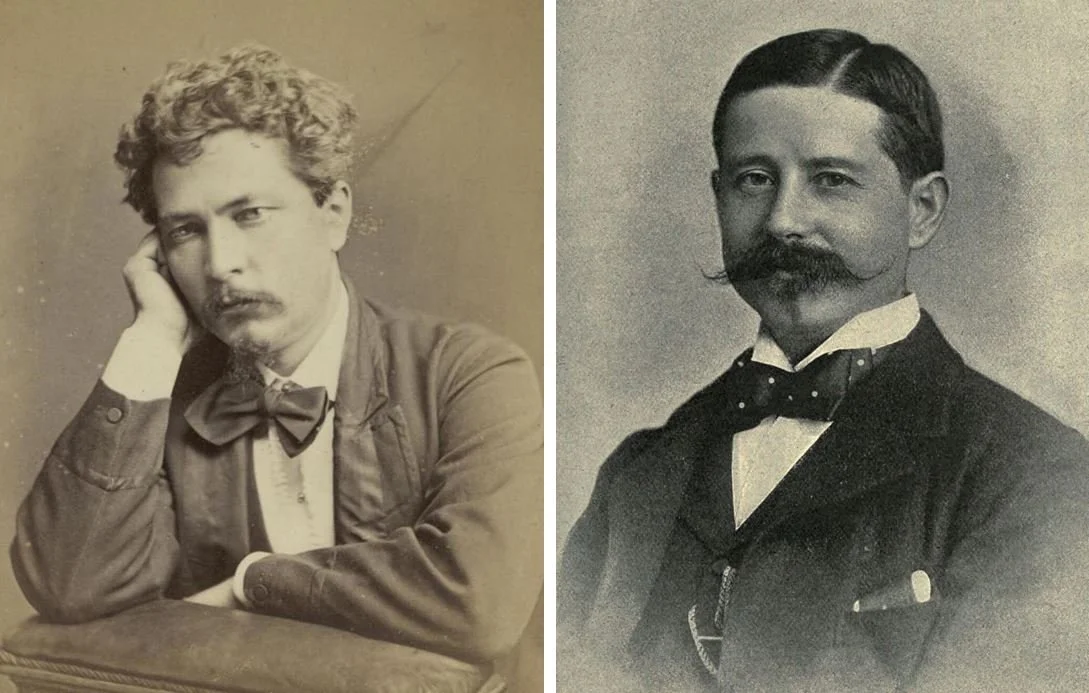

Caption: the two British people mostly associated with the discovery of the Okapi. At left, Welsh explorer, author, colonial administrator Henry M. Stanley (1841-1904) as he looked in the 1870s. At right, English artist, linguist, colonial administrator Harry Johnston (1858-1927) photographed prior to 1895. Both images are in the public domain.

Descriptions that appear to pertain to the Okapi had been obtained by the Belgians by 1897 when an official learnt from members of the Momvus tribe (in north-east Congo) of a creature termed the Ndumbe. It was taller than a buffalo, maroon-brown across the body, striped with white across the rump and legs, and graceful like a zebra in “form and finish” (Spinage 1968, p. 146).

Caption: such is the fame and impact of the Okapi’s discovery that the animal still remains associated with surprising and potential zoological finds. It’s been used as the symbol for at least two cryptozoological organisations, and has a prominent role on the cover of Karl Shuker’s 2012 The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals. The other animal on the cover is the Saola Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, named in 1993 and often inferred to be ‘the Okapi of the late 20th century’.

A new forest zebra. In 1899/1900, Harry Johnston was tasked with returning a group of Mbuti pygmies – abducted by a German and planned for display in Paris (my god, Europeans do not come out of this looking at all good) – to their home in the Congo. Via an interpreter, Johnston learnt what he could from them and asked them about the horse-like Atti; they termed it o’api (pronounced ‘ocwapi’) (Spinage 1968, p. 147) and conveyed to him the idea that it was like a donkey but equipped with the stripes of a zebra.

Once in the Congo, Johnston travelled to the Belgian outpost known as Fort Mbeni. There, he was told by Lieutenant Meura that the animal was familiar, as carcasses were often bought in by the locals. I’m not sure how remarkable we should find it that Meura apparently regarded the retrieval of deceased Okapi as fairly commonplace, and Spinage (1968) speculated that Meura and his people might have been scolded by their superiors by having apparent ready access to this significant zoological discovery and letting outsiders come in and claim it for themselves.

Caption: at left, the two original bandoliers on which the zoological reality of the Okapi was established, as described by Sclater in 1901. At right, a plate from Lankester’s Okapi ‘atlas’ of 1910 in which the two bandoliers were matched up to complete Okapi skins. Numerous of these bandoliers were collected and retained over the years. Images: Sclater (1901); Lankester (1910).

There might not have been a carcass on hand at Fort Mbeni, but there had recently been a skin. Alas, soldiers (part of a local militia, not Belgian soldiers) had cut it into strips, each of which was about 3 ft long and intended for use as a belt or bandolier. Johnston was allowed to take two of these, and he sent them to Philip Sclater of the Zoological Society of London in the November of 1900, who then exhibited them at a meeting of the society in December (Lankester 1902).

Caption: Sclater’s initial naming of the Okapi, wherein it’s a new species of horse.

Sclater published a brief description of them in February 1901, interpreting them as the first evidence for a new living horse that he named Equus(?) johnstoni (Sclater 1901), the question mark denoting the provisional nature of this classification. Hairs from the skin sections were examined under the microscope by W. G. Ridewood and Prof. J. C. Ewart. Ridewood found them to be indistinguishable from those of zebras while Ewart concluded that the hairs were more like those of zebras than those of antelopes.

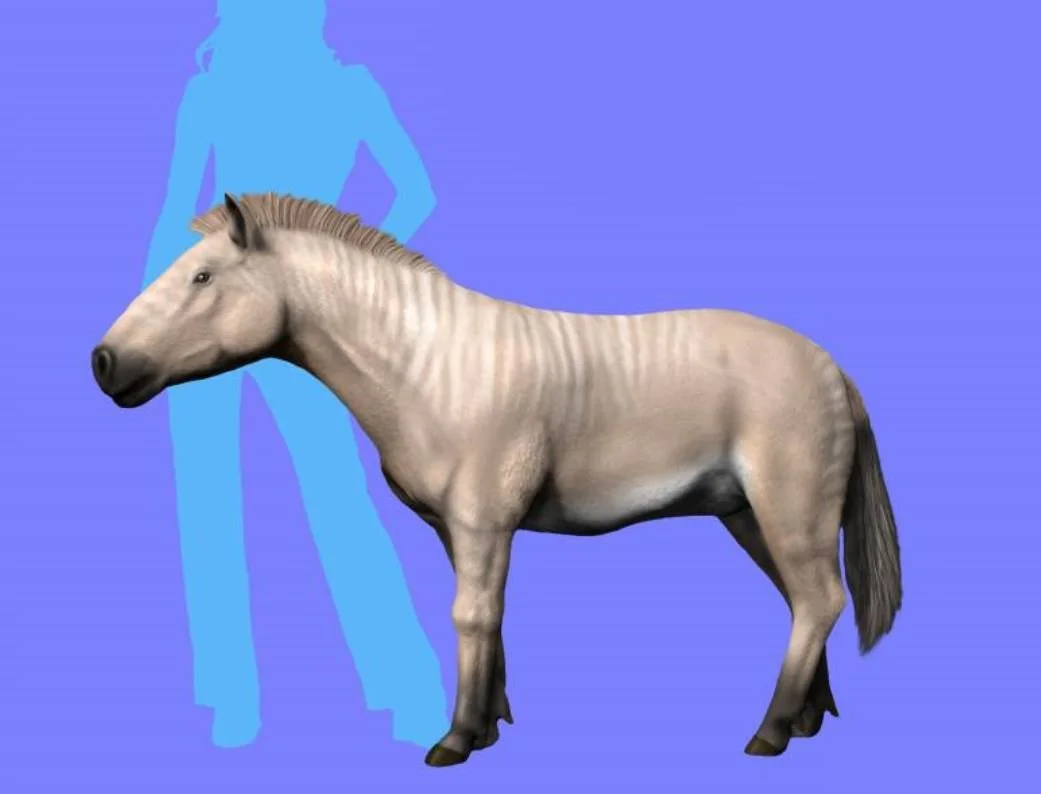

The view that the Okapi was an equid was consistent with Johnston’s view at this time, but references to more than one hoof on each foot led him to think initially that it might be a late-surviving horse like those known from the fossil record, in particular the three-toed Hipparion.

Caption: numerous species of the extinct horse Hipparion have been named from the fossil record of Europe, Asia, Africa and North America, and today it seems remarkable that Johnston thought that he might have been on the track of living specimens of this animal. As is evident from this reconstruction (showing the North American H. forcei), at least some Hipparion species were small relative to living horses. Others were similar in size to modern Equus species. If the Okapi was really imagined as a living Hipparion, it would have to have been even bigger than the largest ones we know of. Image: Nobu Tamura, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Remarkably, Johnston – supplied with guides provided by Lieutenant Meura – was shown apparent Okapi tracks in the Ituri Rainforest. Because they were made by a cloven-hoofed animal, he concluded that they couldn’t be Okapi tracks but must be those made a big antelope, like an eland (a forest-dwelling form of which would still have been a noteworthy discovery), and he refused to follow the trail. The expedition was a disaster anyway, with many members of the group contracting malaria and requiring rescue by the Belgians based at Mbeni. Johnston complained of the humid, oppressive forest interior.

The Okapi is a new living giraffid. Johnston might not have been successful on that trip, but his fortunes changed in March 1901 when Lieutenant Karl Eriksson – second in command at Mbeni – sent Johnston an Okapi skin with a skull, as well as a second, smaller skull. Eriksson broke official Belgian rules in sending this material to Johnston, since specimens of interest were supposed to go to Tervuren Museum* near Brussels (Spinage 1968). Again, the Belgians lost out on getting credit for this find, but – in saying this today – it’s impossible to once again avoid thinking of the colonial exploitation that was happening here and the absence of specific Congolese people from the narrative.

* Today, the Royal Museum for Central Africa or AfricaMuseum. Eriksson was Swedish, not Belgian, but was still expected to follow Belgian rules while based at a Belgian outpost.

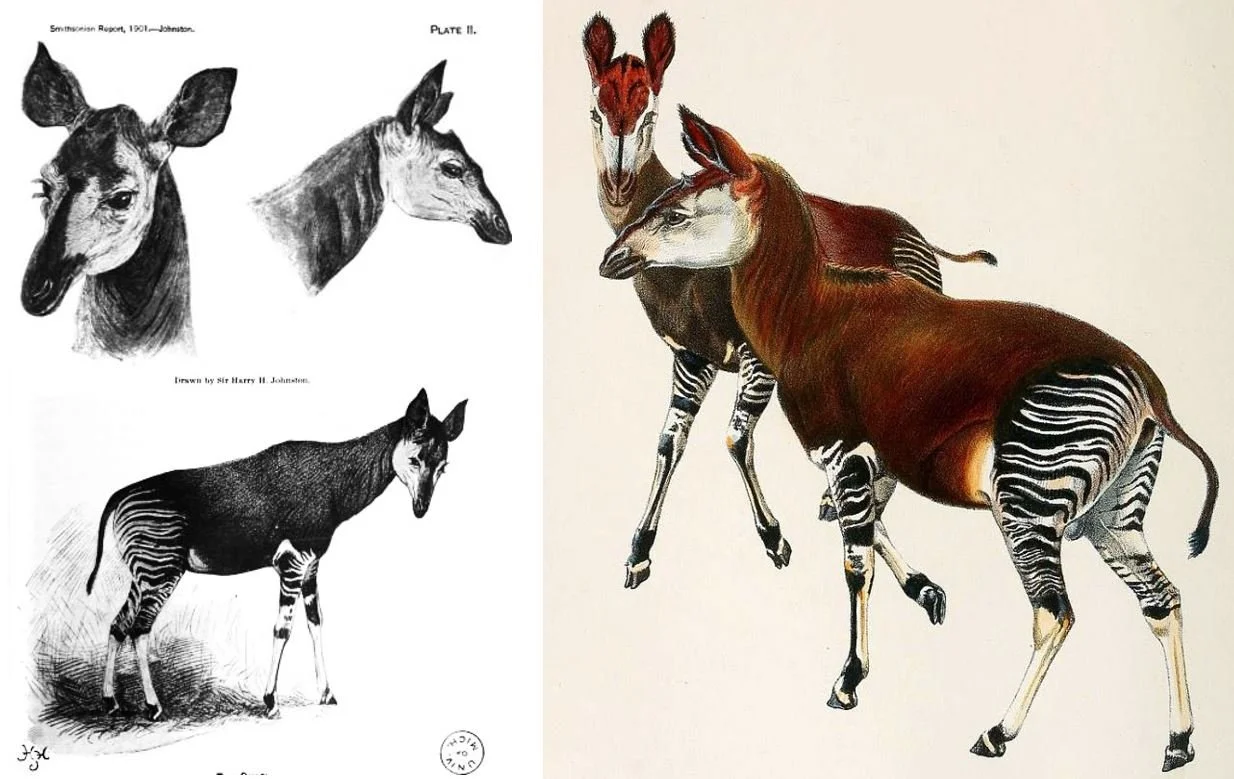

Caption: Johnston was a skilled artist, and produced a number of black and white and colour illustrations of the Okapi based on descriptions and his viewing of the complete skin he obtained. I feel that these illustrations are too pointy-snouted and slender in the limbs, but they’re otherwise highly accurate. Images in public domain.

The skin that Eriksson acquired had cloven hooves, thereby confirming what Johnston had heard. Unfortunately, they were lost by the time the remains reached him, apparently because they became detached and fell away. A few anatomical features (like a bilobed lower canine and an absence of false hoofs) showed immediately that the Okapi was a giraffid. Johnston sent this material to E. Ray Lankester in England, suggesting that it might best be named as a living species of the European fossil giraffid Helladotherium for which he proposed the name H. tigrinum (Lankester 1902).

Caption: a key giraffid character recognised immediately once an Okapi skull was obtained is its bilobed lower canine tooth. This montage – from Lankester (1902) – compares the Okapi lower canine with that of other giraffids living and fossil.

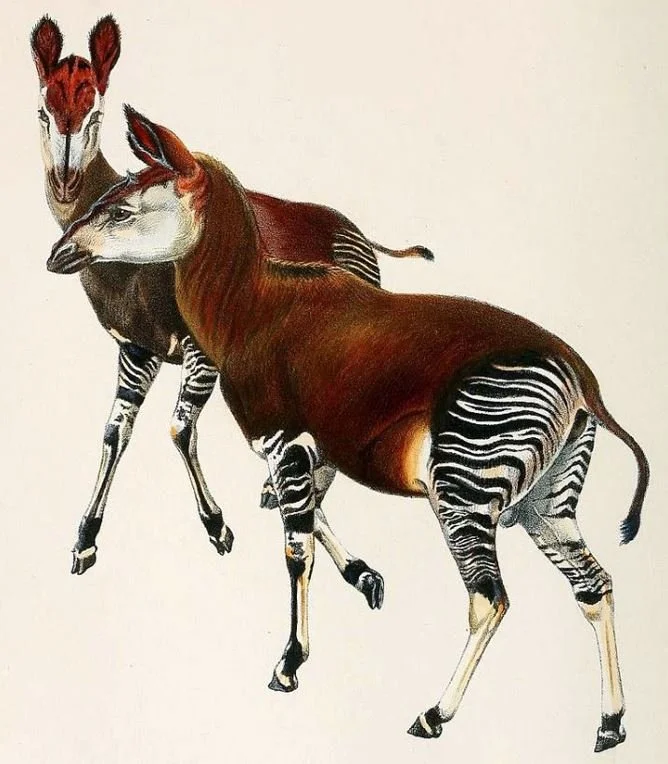

Johnston was a painter, and produced several illustrations, the best known of which is a colour piece depicting two Okapis, both imagined based on his understanding of the skin and skulls. His renditions proved pretty accurate to the look of Okapis in life, one point of interest being that Johnston opted to show the upper margin of the neck continuing in the same approximate line as the dorsal margin of the back, rather than being angled sharply upwards as is typical for artiodactyls like deer and antelopes.

Caption: larger version of the fine Okapi illustration produced by Harry Johnston at the same time as he passed the complete skin to Lankester. Johnston wrote a letter on this painting in March 1901, addressed to Philip Sclater, and explained therein how he had taken great care to properly convey the form and colour of the animal in life. He was concerned that the colour of the coat might have faded by the time it reached England and emphasised its reddish nature in some regions. Image in public domain.

Okapia sees print. The remains sent to England by Johnston did not arrive until July 1901. Lankester, however, knew enough to make a taxonomic decision already, and his announcement of the new generic name Okapia Lankester, 1901 was made on June 18th at a meeting of the Zoological Society*. His first, initial paper was then published in Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (Lankester 1901), this being generally regarded ever since as the first official published outing of the name (even though it appeared in other venues at about the same time due to publicity surrounding the Zoological Society meeting). Sclater’s ‘forest horse’ Equus johnstoni clearly pertained to the same species, so the full name had to be Okapia johnstoni (Sclater, 1901). Actually, Lankester later changed his mind on this, a point we’ll return to in the next article.

* The dates provided here come from Lankester’s own publications on the Okapi (Lankester 1902, p. 282) and from the Zoological Society’s published records. They’re inconsistent with sources which state that the Zoological Society meeting happened on May 7th, and even that the skin and skulls were on display at this time too.

Lankester then published a longer, more detailed description of the Okapi in Transactions of the Zoological Society of London (Lankester 1902), and then a comprehensive atlas of Okapi images and illustrations (Lankester 1910). It has been implied that he planned to write a full descriptive monograph but the appearance of two other works – a monograph written by Julien Fraipont, published in 1907 (Fraipont 1907), and a second by Maurice de Rothschild and Henri Neuville which appeared in 1910 (Rothschild & Neuveille 1910) – apparently caused him to abandon these plans.

Caption: most major European museums obtained Okapi specimens at some point during the 20th century. This one is on show at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. Its fading is typical for dark animals on show in collections. The prominent scars visible on its coat are said to have been caused when it was killed. The animals were trapped in pits and then speared. Image: Darren Naish.

This is far from the end of the Okapi story, but here is where I’ll end for now. Other Okapi species were named after 1901, and claims of earlier ‘discoveries’ of the species were made too. These and other topics will be covered in the next article….

I’ve been saying since 2009 that I’d one day cover the discovery of the Okapi. For previous mentions of Okapis at Tet Zoo, and other giraffid-themed writings, see…

Giraffes: set for change, January 2006

More on what I saw at the zoo, June 2006

Stuffed megamammal week, day 3: Okapi, April 2009

Inside Nature’s Giants part IV: the incredible anatomy of the giraffe, July 2009

Because giraffes are heartless creatures, and other musings, January 2012

Burning Question for World Giraffe Day: Can They Swim?, June 2016

Refs - -

Rothschild, M. de & Neuville, H. 1910. Recherches sur l’okapi et les girafes de l’Est Africain. Annales des Sciences Naturelles Zoologie 9, 1-93.

Fraipont, J. 1907. L’okapi. Ses affinités avec les giraffides vivants et fossils. Bulletin de l’Académie Royale de Belgique 12, 1097-1130.

Heuvelmans, B. 1995. On the Track of Unknown Animals. Kegan Paul International, London.

Lankester, E. R. 1901. On Okapia johnstoni. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1901 (2), 279-281.

Lankester, E. R. 1902. On Okapia, a new genus of Giraffidae, from Central Africa. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 16, 279-307.

Ley, W. 1987. Exotic Zoology. Bonanza Books, New York.

Sclater, P. L. 1901. On an apparently new species of zebra from the Semliki Forest. Proceedings of the Zoological Society 1901 (1), 50-52.

Shuker, K. P. N. 2012. The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals. Coachwhip Publications, Landisville, Pennsylvania.

Spinage, C. A. 1968. The Book of the Giraffe. Collins, London.

Wendt, H. 1959. Out of Noah’s Ark. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.