Among the proudest of my achievements is the publication of Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, DHTLE for short, co-authored with Professor Paul Barrett and published by the Natural History Museum, London. I think it’s fair to say that it’s the flagship ‘dinosaur book’ of the museum. It’s also one of only a handful of dinosaur-themed books written at ‘adult level’. “Finally, a modern, intelligent, trade book on dinosaurs for thoughtful readers”, to quote a reviewer at Quarterly Journal of Biology.

Caption: first edition at left, second edition at right, third edition in the middle. Image: Darren Naish.

The book went to second edition in late 2018; I wrote about its publication here. It got a new cover (this time featuring a fuzzy Tianyulong by Bob Nicholls), but the number of changes made to the text was actually low, predominantly because Paul and I were both chronically overworked at the time and unable to do a thorough job of updating it.

The book has gone to third edition (Naish & Barrett 2023) because, simply put, it continues to sell well. But rather than simply release the book with a few small corrections, we opted to use this as an excuse to correct errors present in the second edition, and to properly change numerous sections of text in view of recent discoveries and proposals. In the rest of this article, I want to note the changes we made: metacommentary is fun (and where else can I do it but here), but to get the full picture you will, of course, want to check the book itself. Buy it here!

Caption: I think often about the ‘ancestors’ of Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, the most important of which are Tim Gardom and Angela Milner’s The Natural History Museum Book of Dinosaurs (first published 1993), and Alan Charig’s A New Look at the Dinosaurs (two editions of which are shown here, first published 1979). Both works have their strengths and weaknesses. Image: Darren Naish.

Without further ado…

Dinosaur origins and dinosaur cousins. Our text and diagrams reflect the recent discovery that lagerpetids – a group of small, long-legged Triassic archosaurs with vaguely theropod-like proportions – are closer to pterosaurs than to dinosaurs, and we’ve also accounted for new discoveries of silesaurids, a near-dinosaur group that have proved diverse in body size and feeding biology. I never did like the John Sibbick reconstruction of Marasuchus included in the previous editions, and this has been replaced by a new one by Gabriel Ugueto.

Caption: massively simplified depiction of the Ornithoscelida phylogenetic hypothesis, as first published by Baron et al. (2017). The image was used in the Tet Zoo article here. Other phylogenetic models have been outed since, some of which even nest Ornithischia within Theropoda. Image: Darren Naish.

Moving to dinosaurs themselves, a decision made early on is that we’d retain our section on the Ornithoscelida hypothesis, this being the idea that theropods and ornithischians are more closely related to one another than either is to sauropodomorphs. This is because at least some of the studies published since the hypothesis was first outed in 2017 have found that those competing views that now exist are equally well supported by the data. It’s not true that the original authors of the first Ornithoscelida paper (of which Paul is one) have abandoned the hypothesis, by the way.

Dinosaur diversity. Numerous small changes have been made to the theropod section, some of which take account of new discoveries pertaining to Dilophosaurus, noasaurid ceratosaurs and baryonychine spinosaurs. We modified the text on Spinosaurus to better reflect continuing disagreement on what it was like, and we also replaced my old skeletal reconstruction of the tyrannosauroid Eotyrannus with a new one provided by Dan Folkes (based on the new data described in my 2022 monograph on this taxon, co-authored with Andrea Cau; Naish & Cau 2022).

Caption: assorted theropod illustrations that appear in the third edition of DHTLE, nearly all of which are new for this edition. (A) Spinosaurus, now with modified tail; (B) Eotyrannus skeletal reconstruction by Dan Folkes; (C) the woodpecker Campethera; (D) Deinonychus skeletal reconstruction by Scott Hartman; (E) the pheasant Phasianus, and (F) the penguin Spheniscus. The birds all feature in a neornithine cladogram. Images: (c) Dan Folkes, (c) Scott Hartman, Darren Naish.

Megaraptorans get slightly more mention than they did in previous editions, the conflict over whether they belong within allosauroids or tyrannosauroids requiring that they get a mention in both sections (I currently prefer a tyrannosauroid position). I made the mistake of implying that megaraptorans are wholly Gondwanan, something that’s not true given the inclusion of Japan’s Fukuiraptor and Thailand’s Phuwiangvenator within the group (a few other possible Laurasian megaraptorans are known are well).

Our ornithischian text has received a reasonable overhaul. A new cladogram (more in keeping with the look of the other cladograms in the book) is featured, and the text on heterodontosaurids has been changed to reflect competition between the view that they’re ‘archaic’ ornithischians outside the clade that includes thyreophorans and cerapodans versus one where they’re within Cerapoda and close to marginocephalians.

Caption: another new illustration included in the third edition of DHTLE, albeit only at small size and in a cladogram. It’s a fuzzy heterodontosaurid. Image: Darren Naish.

Moving to thyreophorans (armoured ornithischians), the text on Scelidosaurus has been updated in view of David Norman’s 2020-2021 monographs, and we also take account of Jakapil, a bipedal ornithischian from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina that, if correctly identified, shows that Scelidosaurus-like thyreophorans persisted for about 100 million years than previously thought (we are of course aware that other identifications for Jakapil have been proposed).

In the ankylosaur section, new text has been added that takes account of the Canadian nodosaurid Borealopelta and the details it preserves on its colour scheme (the immaculately preserved specimen retains the melanosomes it possessed in life). We also take account of the proposed existence of Parankylosauria, a Gondwanan clade named in 2021. We weren’t able to change the ankylosaur text to take account of Raven et al.’s 2023 reclassification of ankylosaurs (this study resurrected Polacanthidae, Struthiosauridae and Panoplosauridae, and did not recognise a formal Nodosauridae) (Raven et al. 2023), so that’ll be something to remember for next time. The stegosaur section has been changed in view of new information on the anatomy of the African Kentrosaurus. It seems that those ‘parascapular’ spines belong on the hips after all.

Caption: the incredible holotype of the Canadian ankylosaur Borealopelta, published in 2017, has to be regarded as one of the best 20 or so Mesozoic dinosaur specimens reported this century. We didn’t have space to show images of it in DHTLE, but we do at least discuss its significance. Here it is on show at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta. Image: ケラトプスユウタ, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Biology, physiology, behaviour. Moving now to the chapters on palaeobiology, the most noteworthy changes are those concerning physiology, eggs and nesting behaviour.

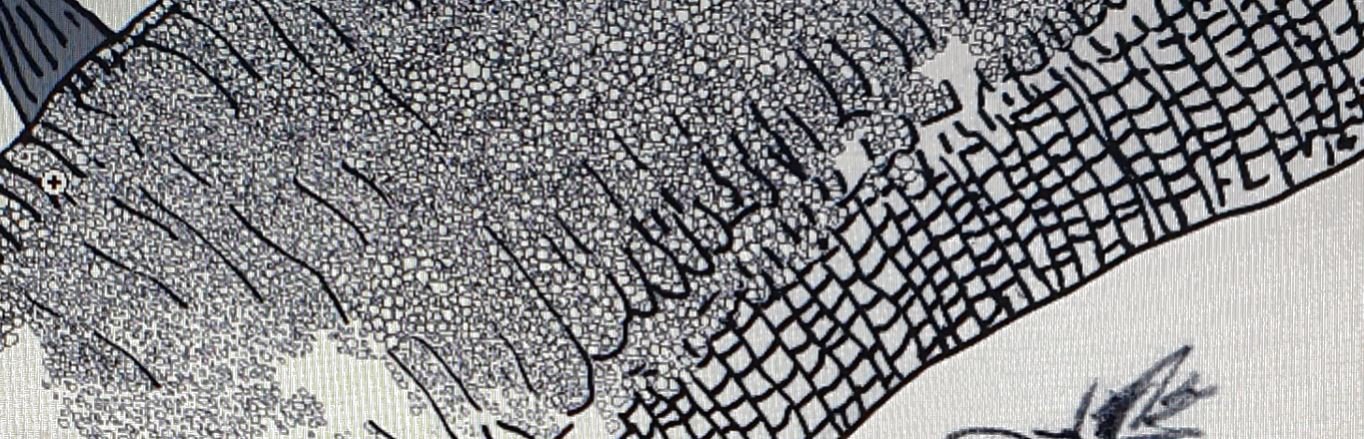

Over time I came to quite dislike the illustration of a ground-feeding Diplodocus I created for the previous editions, both because it’s having to indulge in an unsightly over-extension of its head-neck joint (equivalent to you looking straight up into the sky for an long stretch of time) and because I gave it rows of scales that don’t much resemble the scales known from any sauropod fossil. So a new illustration has been produced. I’m not sure I like that one either.

Caption: a good artist can draw something with a very complex texture (like the scaly body of a giant dinosaur) and use clever artistic shortcuts in order to avoid doing the ridiculous… like, say, drawing every single scale. I lack that skill, and thus am destined to perform the unthinkable. This close-up shows part of my illustration of a diplodocid, the final version of which appears in the third edition of DHTLE.

Recently published studies encouraged us to modify our section on dinosaur physiology, partly to take account of Jasmina Wiemann et al.’s 2022 histology-based study. Therein, non-bird dinosaurs were mostly found to be endothermic, though some ornithischian lineages were posited as secondarily ectothermic (Wiemann et al. 2022). I think that the argument for ‘mesothermic’ dinosaurs – popular at about the time that we produced the first edition – is looking weak today and a few tweaks to the text of the third edition reflect this.

On eggs and nests, the most obvious change is incorporation of the discovery that soft-shelled eggs (‘leathery-shelled’ is a better descriptor) were present in at least some dinosaur groups. Recent discoveries pertaining to the colour and patterning of Mesozoic maniraptoran eggs are also alluded to.

The great extinction, and birds! Our section on the end-Cretaceous extinction always did, a critical reader might argue, somewhat miss the mark. This is because we opted to endorse an ‘integrated scenario’ where the effects of volcanism were combined with the Chicxulub impact in a terrible dual event. I now think that that was a mistake and that it was the bolide impact alone that’s sufficient to explain the extinction. Recent research backs this up, and in fact one 2020 study found that the atmospheric release of volcanic ash may have mediated the impact by lowering temperatures that would otherwise have skyrocketed (Chiarenza et al. 2020).

Caption: new cladograms appear in the third edition of DHTLE. Images: Darren Naish.

One of the points we emphasize throughout DHTLE is that birds are dinosaurs, and that we’re now well past the point at which we can ignore this. Palaeontologists who work on the dinosaurs of the Mesozoic often pretend that birds don’t exist, as if the word ‘dinosaur’ is synonymous with ‘non-bird dinosaur’. Those paying attention will know that much has happened in neornithine bird phylogeny this century, a consequence being that there’s an approximate consensus on the shape of the tree. Some of the details depicted in the tree used previously doesn’t reflect that consensus, so a new one appears in the third edition. I owe thanks to palaeornithologist Albert Chen for discussion of this issue.

Caption: your reminder that ‘dinosaur’ is not synonymous with ‘non-bird dinosaur’. Stop pretending that it is. Also, it’s just not true that all workers specializing on Mesozoic dinosaurs are unfamiliar with modern ones, and for much more on that subject see my October 2023 article on Feduccia’s bizarre Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs book. Images: Darren Naish.

We also added a new illustration of Gastornis. We previously featured one by John Sibbick where the animal is shown as an arch-predator, grabbing a small horse. A big herbivorous bird might still have grabbed small horses on occasion, but that image is looking dated now so it’s gone.

And that’s where we’ll end things. This is a non-trivial amount of change, enough to make the third edition worth owning even if you own the second or first ones. And if you don’t own the book at all, now is definitely the right time to obtain a copy that’s more up to date with respect to our present state of knowledge.

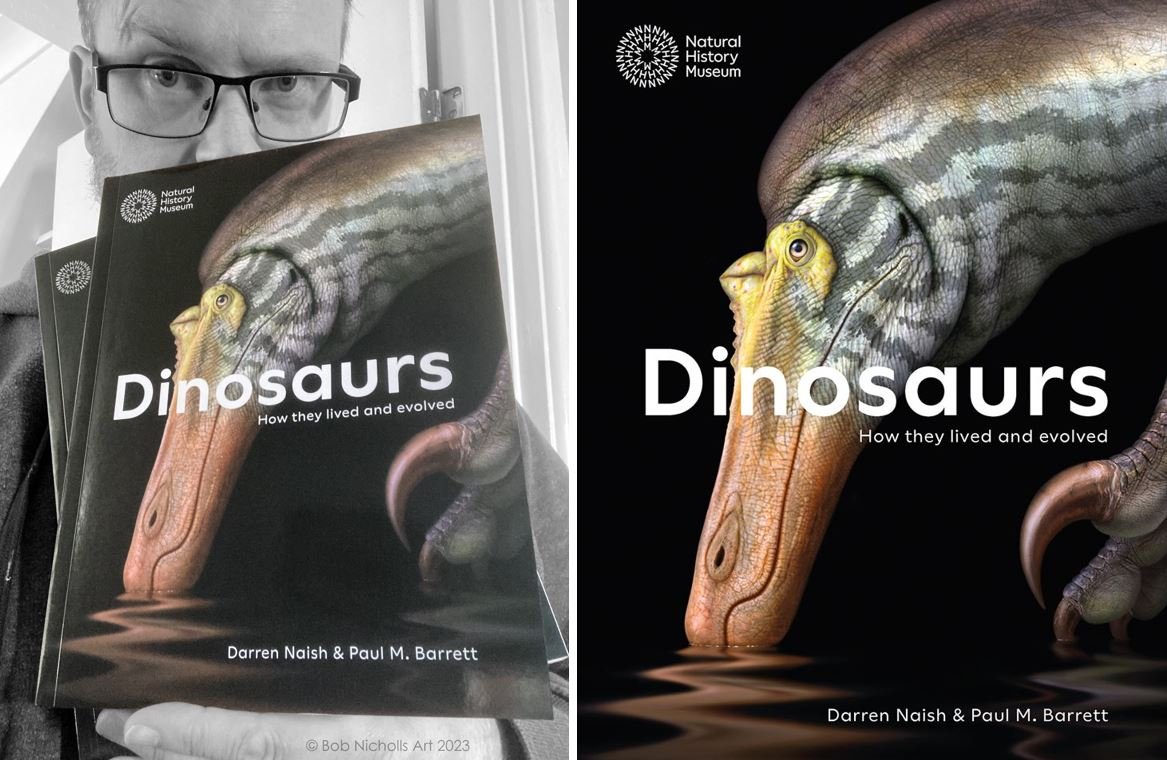

Caption: Bob Nicholls is an absolutely joy to work with, and is an incredibly hard worker to boot. Massive thanks are owed to him for the brilliant cover art he produced for Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. His website is here. Images: (c) Bob Nicholls.

Oh – I mentioned earlier than the second edition featured a wonderful and entirely novel reconstruction of Tianyulong on its cover, produced by British palaeoartist Bob Nicholls. I’m very pleased to say that Bob was once again able to generate novel cover art, this time depicting the English baryonychine Ceratosuchops. That animal – named in 2021 by a mostly British team (Barker et al. 2021) – is fitting for the cover of a book published by the UK’s premiere palaeontological institution, associated as it is with the naming and study of the baryonychine exemplar Baryonyx itself by the museum’s Alan Charig and Angela Milner.

Caption: Baryonyx has a special place in the history of British dinosaurs, in our understanding of spinosaurid theropods, and in the palaeontological research of London’s Natural History Museum. These two images are fairly iconic: at left, the late Bill Walker holds the holotype claw; at right, a life reconstruction by John Holmes, produced in 1987. Images: (c) Natural History Museum, London.

Thanks to everyone who’s bought Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved – whatever edition that might be – and special thanks to those who’ve said positive things about it in reviews, have recommended it to others, and have had cause to use it as a way of introducing other people to our current understanding of dinosaurs and their world.

Finally, it’s worth saying that the third edition is, so far, difficult to get in some parts of the world, and I know that some people have made an online purchase of what they thought was the third edition, only to then receive the second edition in the post. In view of this you have to be ultra-careful if attempting to buy the third edition online. For those in the UK, the edition on sale via the NHM shop is definitely the third edition, and in fact purchase from that site is probably the best way to ensure that you’re getting it (other than by picking it up by hand in a shop).

Caption: proof that the third edition is on sale in the Natural History Museum shop, a photo from January 2024. Image: Darren Naish.

For previous Tet Zoo articles relevant to the issues covered here, see…

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

Ornithoscelida Rises: A New Family Tree for Dinosaurs, March 2017

The Second Edition of Naish and Barrett’s Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2018

Dr Angela Milner and the Discovery of Baryonyx, August 2021

Two New Spinosaurid Dinosaurs from the English Cretaceous, September 2021

Refs - -

Baron, M. G., Norman, D. B. & Barrett, P. M. 2017. A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution. Nature 543, 501-506.

Chiarenza, A. A., Farnsworth, A., Mannion, P. D. & Allison, P. A. 2020. Asteroid impact, not volcanism, caused the end-Cretaceous dinosaur extinction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 17084-17093.

Raven, T. J., Barrett, P. M., Joyce, C. B. & Maidment, S. C. R. 2023. The phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the armoured dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 21, 2205433.

Wiemann, J., Menéndez, I., Crawford, J. M., Fabbri, M., Gauthier, J. A., Hull, P. M., Norell, M. A. & Briggs, D. E. G. 2022. Fossil biomolecules reveal an avian metabolism in the ancestral dinosaur. Nature 606, 522-526.