Today is May the 4th (2019), so what better thing to post at TetZoo than a brief take on Star Wars and its zoology crossovers.

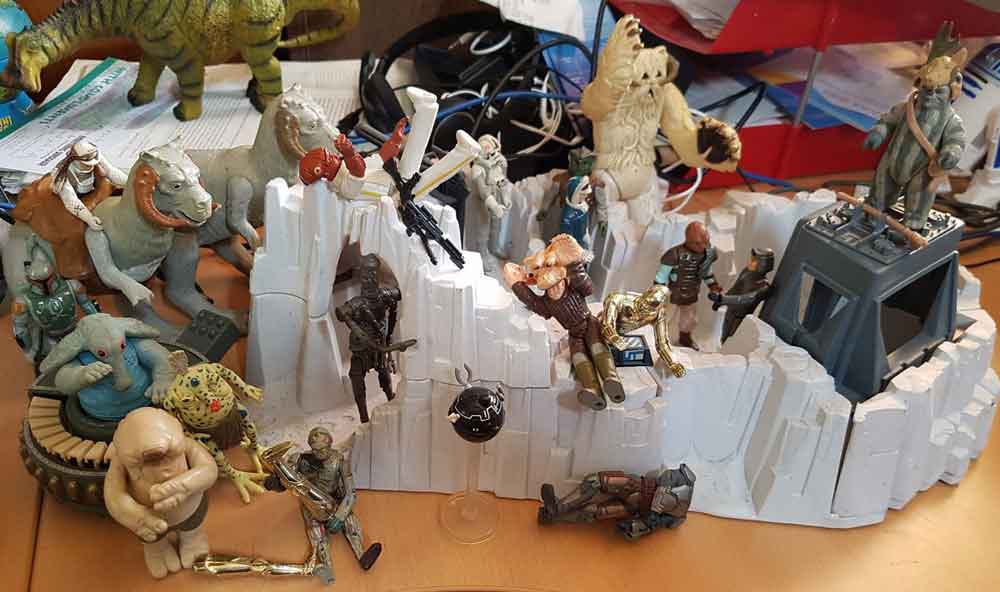

Caption: Star Wars creatures. From left to right: tauntauns, opee, wampa, Max Rebo (in ball organ), Sy Snootles, Droopy McCool, Amanaman, rancor. We’ll be talking about some of these creatures below. Image: Darren Naish.

Like most people of my age (I’m a child of the 1970s), the original Star Wars films had a huge influence on me. In fact, I’m a massive Star Wars nerd who knows an inappropriate amount of things about the droids, bounty hunters, planets, characters and plot lines of the original trilogy… aaaand the other films too. Those who listen to the TetZoo podcast will know that I’m gradually working my way through the entire script to The Empire Strikes Back, in part because I’m such a huge fan of AT-ATs and everything else featured in the section of the movie set on Hoth.

While I could easily write vast swathes of useless nonsense on the Star Wars movies and my thoughts on them (fun fact of the day: Leia calls Luke and Han “moon jockeys” in the original script for Empire), let’s focus on a few things that have some kind of relevance to the TetZooniverse.

Caption: that Krayt Dragon skeleton sure looks a lot like a replica sauropod with a semi-fictional head. Now we know why.

The Krayt Dragon. Today it’s fairly well known among movie buffs that the Krayt Dragon skeleton featured on Tatooine in the original Star Wars (today Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope) is actually the same replica skeleton – the exact same prop – that stands in for Diplodocus in the 1975 Disney movie One Of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing. I’ve written about this at TetZoo, and it’s been covered at SV-POW! as well. Also well known is that the Star Wars crew left some, most or even all of the skeleton out there in the Tunisian desert (wow, epic littering), and that bits and pieces of it have been collected from the site by geologists, palaeontologists and others over the years.

Caption: a scene from One Of Our Dinosaurs Is Missing. Yup, that skeleton looks familiar. These days it’s funny to think that it’s meant to be one and the same as Dippy of NHM London fame, and that it ended its life a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away. Image: IMDB.

On the subject of sauropods, also worth noting is that the CG Rontos of the modified editions of episode IV are tweaked versions of the Jurassic Park brachiosaur, but with some additions inspired by Paraceratherium, the giant rhino.

Of wampas and tauntauns. Hoth’s wampa – or, the Hoth wampa, in fact – is one of my favourite Star Wars creatures. It’s assumed that the wampa was inspired by the pop-culture idea of the Himalayan yeti, and designed to be a frightening, hypercarnivorous version of this creature (even though yetis are dark, and not snow-coloured). The wampa of the movie undergoes several radical changes in appearance if you watch closely, a consequence of the fact that various different models, suits and puppets were used for different scenes. The original toy looks very odd in the face, I believe because the Kenner model-makers were given insufficient information on its final look. Oh: why is it that herbivorous tauntauns and hypercarnivorous wampas both have gnarly, curling horns on the side of the face? The real answer is “because it looks cool”, but… is there an in-universe explanation that explains this unusual detail of convergent evolution?

Caption: tauntauns started life as kangaroo-dinosaur creatures, the first concept art by Joe Johnston actually making them look rather like fuzzy theropods (could Johnston have been inspired by the fuzzy dinosaur artwork that had appeared in Bakker’s Scientific American article?). Today they’re one of the most-loved creatures of the canon. Image: StarWars.com.

Reptomammals and reptavians. If you’re curious about the phylogeny of Star Wars creatures, there have been several efforts to devise taxonomic schemes that reflect phylogeny. Wampas, tauntauns and rancors are all reptomammals, apparently. This is a group of animals that combine reptile- and mammal-like traits, and can be furry, scaly, or a combination of the two. Then there are reptavians, which similarly combine reptile and bird traits. My favourite example of a reptavian is the Varactyl, a creature that looks like a giant day gecko but has a hooked bill and a covering of iridescent feathers (Obi Wan rides one, called Boga, in Revenge of the Sith).

Caption: turns out that the species is called a Varactyl, and the individual Obi-Wan is riding is called Boga. Ok. Image: Lucasfilm Ltd.

This creature fascinates me because its sprawling locomotion and sinuous flexing of its body during running mean that its ribcage is surely undergoing a lot of shape change, yet it’s yelling its head off all the while. In other words, the Varactyl has circumvented Carrier’s constraint: the biomechanical problem whereby animals that flex their bodies laterally during running have their breathing (and thus vocalising) constrained at the same time.

Back to reptomammal and reptavian affinities… I’m sure there’s some stuff in Star Wars canon about how the members of these clades (are they clades?) came to be widely distributed across planets and even solar systems, but otherwise this always seems to be a stumbling block for the ‘these creatures which are spread across the galaxy all have close evolutionary relationships’ idea common to the Star Wars universe.

Caption: rancors have featured in a huge number of Star Wars stories now. This artwork is pretty badass (the individual shown here is much bigger than the young one Skywalker encountered in Jabba’s palace). Image: reddit (original here).

While – even today – I have my own fair share of Star Wars toys (virtually all pertaining to the original films alone), I don’t have a vast number of the creatures. Just two tauntauns, a wampa, a rancor, an opee (from The Phantom Menace), and a few of my favourite humanoids, like Amanaman. It’s virtually always possible to recognise which real-world creatures inspired the designs of Star Wars creatures, and if there’s a criticism of the look favoured throughout the various iterations of the franchise it’s that the animals are too Terran. Virtually everything is identifiable as a reptile, bird, mammal or fish of Earthy sort. To take just a few examples… tauntauns are bipedal camels (with a hint of dinosaur), while Amanaman has clear cobra vibes to its look [UPDATE: I was totally wrong on this. Turns out that Amanaman was inspired by flatworms!] . The Opee sea killer is obviously just an anglerfish and crustacean stuck together.

Caption: I’ve proudly retained at least some of my Star Wars toys. Image: Darren Naish.

Whitlatch and Carrau’s The Wildlife of Star Wars. Anyone interested both in Star Wars and in imaginary or speculative animals will be aware of Terryl Whitlatch and Bob Carrau’s beautiful book The Wildlife of Star Wars, which features scores of amazing illustrations depicting the animals of the Star Wars universe and such things as their ecological interactions and lifecycles.

Caption: Whitlatch & Carrau’s The Wildlife of Star Wars, front cover. Image: amazon.co.uk.

Terryl designed many of the creatures used in the prequel trilogy, and came up with such things as the humanoid amphibian Jar-Jar Binks (and hence his species, the gungans) and the various aquatic predators of Naboo. Among these is the Sando aqua monster, a quadrupedal super-predator that reaches 200 metres in length. Concept art shows that the Sando aqua monster was originally going to be built like an immense, aquatic cat, a really cool idea which I can’t help but think of when I see footage of jaguars foraging and swimming underwater. Alas, someone somewhere didn’t like this, so it was given a wide-mouthed, whale-like head and ended up looking less interesting (in my opinion).

Caption: a screengrab from one of those amazing pieces of film that show jaguars swimming underwater. This footage comes from what I think is a Brazilian zoo with a special glass-fronted swimming pool.

And while there’s much more I could say, I’ll stop there. And I didn’t once mention the fact that I previously worked with Jez Gibson-Harris, maker and operator (with others) of Jabba the Hutt.

For vaguely relevant TetZoo articles, see…

Bigfoot’s Genitals: What Do We Know?, August 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019