UPDATE (added 13th March 2020): since I published the article below, two relevant matters have come to attention, both of which have implications for the fossil discussed in the article.

Caption: article at left from New Scientist; article at right from New York Times.

The first is that the extraction of amber from the locations concerned is linked with significant humanitarian issues. These make the continued publication and promotion of Burmese amber fossils look unethical; I was only dimly aware of these when writing the article and now regret my (minor) role in the promotion of this discovery (I did plan to delete the article but, on advice, was encouraged to keep it, but add the disclaimer you’re reading now). You can read about the humanitarian issues here, here and here.

Secondly, a number of experts whose opinions I respect have expressed doubts about the claimed theropod status of the fossil discussed below and have argued that it is more likely a non-dinosaurian reptile, perhaps a drepanosaur or lepidosaur (and maybe even a lizard).

Caption: a few artists have already produced speculative life reconstructions of Oculudentavis as a lepidosaur or similar reptile. It would have to be a big-brained, shallow-snouted, big-eyed one. Image: (c) Mette Aumala, used with permission.

I did, of course, consider this sort of thing while writing the article but dismissed my doubts because I assumed that - as a Nature paper - the specimen’s identity was thoroughly checked and re-checked by relevant experts before and during the review process, and that any such doubts had been allayed. At the time of writing, this proposed non-dinosaurian status looks likely and a team of Chinese authors, led by Wang Wei, have just released an article arguing for non-dinosaurian status. I don’t know what’s going to happen next, but let’s see. The original, unmodified article follows below the line…

—————————————————————————————————————————————

If you’ve been paying attention to 21st century palaeontological discoveries you’ll know that our understanding of Cretaceous vertebrate diversity has been much enhanced in recent years by the discovery of animals preserved within amber.

Caption: a number of really interesting vertebrate fossils in amber have been published in recent years. Among them are the two partial enantiornithine bird wings shown at left (both from Xing et al. 2016a), and the tiny anguimorph lizard Barlochersaurus winhtini (from Daza et al. 2018). Images: Xing et al. (2016), CC BY 4.0, Daza et al. (2018).

These include lizards and snakes (Daza et al. 2016, 2018), a segment of dinosaur tail originally identified as that of a non-bird theropod (Xing et al. 2016b), and various small birds (e.g., Xing et al. 2016a, 2017, 2018, 2019), all of which belong to the archaic, globally distributed group known as the enantiornithines or opposite birds. Today sees the latest of such discoveries, and it’s the most remarkable announced so far. It is – in fact – among the most remarkable of Mesozoic fossils ever announced, and I say this because of the implications it has for our understanding of Mesozoic vertebrate diversity.

Caption: life reconstruction of Oculudentavis khaungraae Xing et al., 2020, depicting it as a tree-dwelling avialan theropod with partly colourful plumage. Image: (c) Gabriel Ugueto, used with permission.

The fossil in question, described in the pages of Nature by Lida Xing, Jingmai O’Connor and colleagues, is the complete, anatomically pristine but minuscule skull of a maniraptoran theropod – specifically, an archaic bird – named Oculudentavis khaungraae (Xing et al. 2020). The skull is preserved in a small amber block (31.5 x 19.5 x 8.5 mm) dating to the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous (making it about 99 million years old). Like virtually all recently described amber vertebrates, it’s from Myanmar (Xing et al. 2020).

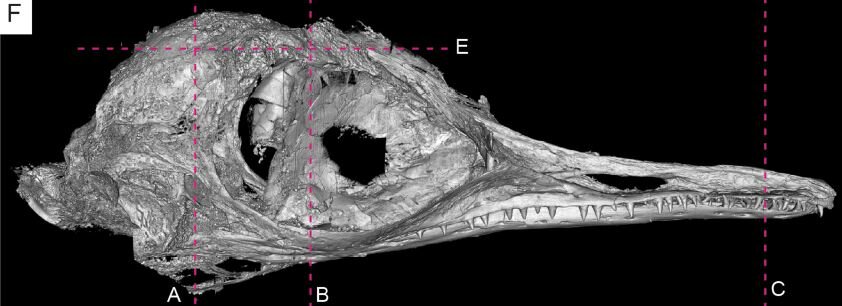

Caption: one of several images of the tiny Oculudentavis skull provided by Xing et al. (2020), this one (from their Extended Data) showing the specimen in left lateral view. The scale bar is 2 mm. Image: Xing et al. (2020).

When I say that this fossil is ‘minuscule’, I’m not kidding: the entire skull – the whole skull – is 14 mm long (1.4 cm; not a typo)*. This means that – at a very rough guess – the whole animal was around 90 mm (9 cm) long, an estimate I arrived it by producing a very schematic skeleton which equips the animal with a long tail. Xing et al. (2020) very rightly compare Oculudentavis with small hummingbirds: if it had a long bony tail (which it should have, given its inferred phylogenetic position; read on), it would have been longer than the tiny Mellisuga hummingbirds, the total lengths of which are around 50-60 mm, but not by much. It was unbelievably tiny.

* I’m frustrated by the fact that the authors don’t – so far as I can tell – provide the length of the entire skull anywhere in the paper, nor is there a table of measurements or an effort to estimate the animal’s complete size. Which is weird, because surely this is the most interesting thing about it.

Caption: a very rough, semi-schematic skeletal reconstruction of Oculudentavis which I produced in order to gain a rough idea of possible size. As you can see, it would have been tiny. The overall form of the skeleton is based on that of jeholornithiform birds; read on. Image: Darren Naish.

The skull of Oculudentavis has a typical ‘birdy’ look. It has a longish, shallow rostrum, large eye sockets, a lot of bone fusion (no, it isn’t a baby) and a rounded cranium where the section posterior to the eyes is short and compact (Xing et al. 2020). The nostrils are retracted, there’s no trace of an antorbital fenestra, the bony bars beneath the eye sockets bow outwards, and there’s a complete bony bar separating each eye socket from the openings at the back of the skull (Xing et al. 2020).

Caption: digital scan of the skull of Oculudentavis in right lateral view (from the Extended Data of Xing et al. 2020). Note the overall toothiness. The dotted lines here show where slices were recorded during the scanning process. Image: Xing et al. (2020).

It’s a toothy little beast, with an atypically high number of conical (or near-conical) teeth lining its jaws all the way back to beneath the eye socket. This is unusual, since the toothrow in toothed birds and bird-like theropods in general normally stops well anterior to the eye. Another unusual feature is that the teeth aren’t located in sockets but are either fused to the jaw bones (the acrodont condition) or located within grooves that extend along the length of the jaws (the pleurodont condition) (Xing et al. 2020). The teeth look prominent, such that it’s hard to understand how they could be sheathed by lip tissue, nor is any such tissue preserved. Remember that beak tissue doesn’t occur in the same part of the jaws as teeth do, so Oculudentavis wouldn’t have had a true horny covering on its jaws. I assume that it had ‘lip’ tissue sheathing its teeth (except perhaps for the tips of the longest ones), as do other terrestrial tetrapods.

Caption: speculative life reconstruction of Oculudentavis, its feathering and other details inspired by Jeholornis and other archaic members of Avialae. I’ve depicted it on the forest floor but am not necessarily saying that this is where it spent all of its time. Image: Darren Naish.

The eyes are directed laterally and the authors note that Oculudentavis likely didn’t have binocular vision (Xing et al. 2020). The sclerotic rings are huge and fill up most of the eye sockets. Xing et al. (2020) use the relative size of the eyes and their sclerotic rings to make inferences about the activity patterns and visual abilities of this animal: they think that Oculudentavis was likely day-active, had relatively small pupils, and perhaps had “unusual visual capabilities”.

The fossil doesn’t just consist of the animal’s bones alone, because synchrotron scanning reveals the presence of a brain (which is about as wide as it is long). Meanwhile, the bony palate preserves traces of its original tissue covering. This is decorated with numerous papillae, the first time such structures have been reported in a fossil theropod (Xing et al. 2020). The authors also refer to a tongue (!!) but it isn’t possible to make this out in the figures they provide, nor do they label it.

Combined, what do these features tell us about the lifestyle and ecology of Oculudentavis? The well-fused skull, prominent teeth and large eyes suggest that this was a predator, presumably of small arthropods. The soft papillae on the palate are of the wrong sort for fish-eating (Xing et al. 2020). Its tiny size and forest habitat imply that it was arboreal or scansorial – as suggested by Gabriel’s artwork above – but the animals that surround it in the cladogram are mostly terrestrial, so the possibility that it foraged in leaf litter or took regular trips to the forest floor are also conceivable, perhaps. Could it have been a predator of worms, molluscs or even tiny vertebrates, like a dinosaurian shrew?

Caption: Oculudentavis would have looked noticeably small relative to other Mesozoic birds, though not absurdly so. It’s compared here with Archaeopteryx (at upper left) and an assortment of others, most of which are enantiornithines. These illustrations are for my in-prep giant textbook project. Image: Darren Naish.

What sort of bird is Oculudentavis? For starters, it’s the presence of fused premaxillary and braincase bones, the position and size of the nostril, eye, postorbital region and domed cranium which strongly indicate that Oculudentavis is a member of Avialae, the bird lineage within Maniraptora (though note that the authors prefer the term Aves for said lineage). They included it within a phylogenetic analysis and found it to be one step more crown-ward (meaning, one node on the cladogram closer to living birds) than is Archaeopteryx, which is surprising because it makes Oculudentavis one of the most archaic members of the bird lineage (Xing et al. 2020). This could mean that birds underwent acute miniaturisation almost as soon as they evolved. Several authors – myself and colleagues included (Lee et al. 2016) – have argued beforehand that theropods on the line to birds underwent a gradual and pervasive decrease in size, but we didn’t (and couldn’t) predict that a size decrease of this sort occurred so early in bird history.

Caption: theropods display a continuous, pervasive decrease in size when we look at the inferred size of ancestral species at successive nodes across the lineage leading to birds. From left to right, this illustration by Davide Bonnadonna shows the ancestral neotheropod (~220 Million years old), the ancestral tetanuran (~200 myo), the ancestral coelurosaur (~175 myo), the ancestral paravian (~165 myo), and Archaeopteryx (150 myo). Image: Davide Bonnadonna.

A World of Tiny Cretaceous Theropods? A key thing here is that we only know about this animal because of its preservation in amber: the rest of the fossil record mostly – the authors suggest – robs us of tiny vertebrates such as this. Could there actually have been many hummingbird-sized miniature theropods of this sort?

Caption: Xing et al. (2020) don’t provide a size estimate for Oculudentavis, but they do provide these silhouettes, which show Oculudentavis to scale with a hummingbird and chicken (and part of an ostrich is just visible at far right). Image: Xing et al. (2020).

Here’s where Xing et al.’s (2020) cladogram become especially interesting. The position they propose for Oculudentavis requires that its lineage originated about 150 million years ago, and yet Oculudentavis itself is about 99 million years old. Its lineage, therefore, is at least 50 million years long, in which case there could have been many of these tiny avialan dinosaurs (here, I have to resist the urge to talk about the hypothetical tree-climbing small dinosaurs of Dougal Dixon and George Olshevsky). I emphasise that this speculation assumes that the phylogenetic position Xing et al. (2020) infer is correct; it may not be. Indeed 10% of their trees found Oculudentavis in a different position: within enantiornithines, a possibility which seems ‘more right’ given the identity of other Burmese amber birds. With just a skull to go on, we obviously need more material before we can be especially confident on its phylogenetic position. And on that point, I won’t be surprised if it turns out that Oculudentavis does end up occupying a different position within maniraptoran theropods from the one which Xing et al. (2020) prefer. But none of this affects its minuscule nature, and that’s the real killer point here.

Caption: part of a time-calibrated theropod tree (from Wang & Zhou 2017). According to Xing et al. (2020), Oculudentavis occupies a position more root-ward than Jeholornithiformes, but more crown-ward than Archaeopteryx. If correct, this means that its lineage originated during the latest part of the Jurassic. Image: Wang & Zhou (2017).

What About Other Fossil Vertebrates? If tiny, tiny Cretaceous theropods have remained unknown to us until now, what about other terrestrial vertebrates? I’d always assumed that the truly tiny frogs, lizards and other vertebrates of the modern world – those less than a few centimetres long – were recently evolved novelties of the Cenozoic. But maybe this is completely wrong. Maybe animals of this sort were present in the Mesozoic too, and maybe we’ve missed them due to a size filter which can only be filled by fossils discovered in amber?

Caption: the modern world is inhabited by truly tiny lizards and frogs, like this c 3cm SVL Brookesia chameleon and c 1cm Stumpffia frog. Were similarly tiny tetrapods also around in the Cretaceous? Images: (c) Mark D. Scherz, used with permission.

Time will tell. This is really exciting stuff.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to this one, see…

Bird behaviour, the ‘deep time’ perspective, January 2014

50 million years of incredible shrinking theropod dinosaurs, July 2014

The Romanian Dinosaur Balaur Seems to Be a Flightless Bird, June 2015

The Most Amazing TetZoo-Themed Discoveries of 2018, December 2018

A Multi-Species Nesting Assemblage in the Late Cretaceous of Europe, February 2019

Refs - -

Daza, J. D., Bauer, A. M., Stanley, E. L., Bolet, A., Dickson, B. & Losos, J. B. 2018. An enigmatic miniaturized and attenuate whole lizard from the mid-Cretaceous amber of Myanmar. Breviora 563, 1-18.

Daza, J. D., Stanley, E. L., Wagner, P., Bauer, A. M. & Grimaldi, D. A. 2016. Mid-Cretaceous amber fossils illuminate the past diversity of tropical lizards. Science Advances 2 (3), e1501080.

Wang, M. & Zhou, Z. 2017. The evolution of birds with implications from new fossil evidences. In Maina, J. N. (ed) The Biology of the Avian Respiratory System. Springer International Publishing, pp. 1-26.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., O’Connor, J. K., Bai, M., Tseng, K. & Chiappe, L. M. 2019. A fully feathered enantiornithine foot and wing fragment preserved in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Scientific Reports 9, 927.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., Wang, M., Bai, M., O’Connor, J. K., Benton, M. J., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Tseng, K., Lockley, M. G., Li, G., Zhang, Z. & Xu, X. 2016a. Mummified precocial bird wings in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Nature Communications 7, 12089.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., Xu, X., Li, G., Bai, M., Scott Persons IV, W., Miyashita, T., Benton, M. J., Zhang. J., Wolfe, A. P., Yi, Q., Tseng, K., Ran, H. & Currie, P. J. 2016b. A feathered dinosaur tail with primitive plumage trapped in mid-Cretaceous amber. Current Biology 26, 3352-3360.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., McKellar, R. C., Chiappe, L. M., Bai, M., Tseng, K., Zhang, J., Yang, H., Fang, J. & Li, G. 2018. A flattened enantiornithine in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber: morphology and preservation. Science Bulletin 63, 235-243.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., McKellar, R. C., Chiappe, L. M., Tseng, K., Li, G. & Bai, M. 2017. A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine (Aves) hatchling preserved in Burmese amber with unusual plumage. Gondwana Research 49, 264-277.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., Schmitz, L., Chiappe, L. M. McKellar, R. C., Yi, Q. & Li, G. 2020. Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar. Nature 579, 245-249.