Time for the second part in my Minnesota iceman series. The article you’re about to read was originally published at ver 3 (the Sci Am years) in two separate parts. For the first part on the Minnesota iceman, go here…

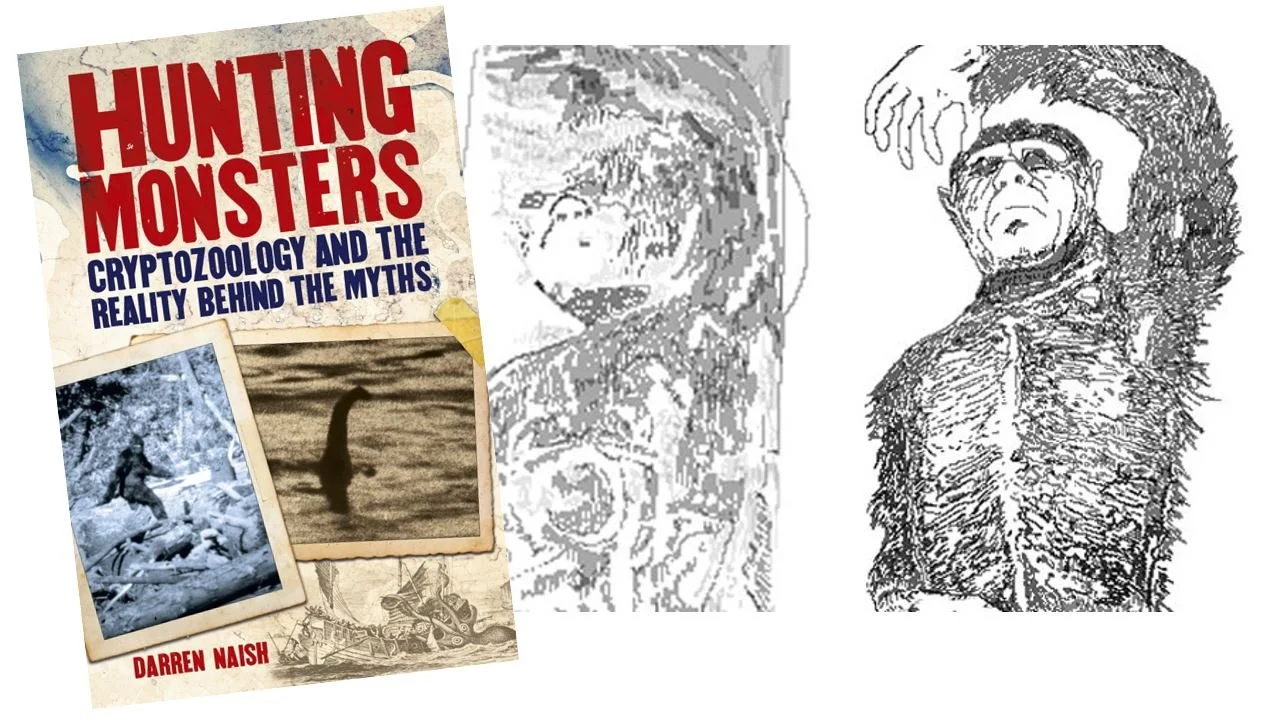

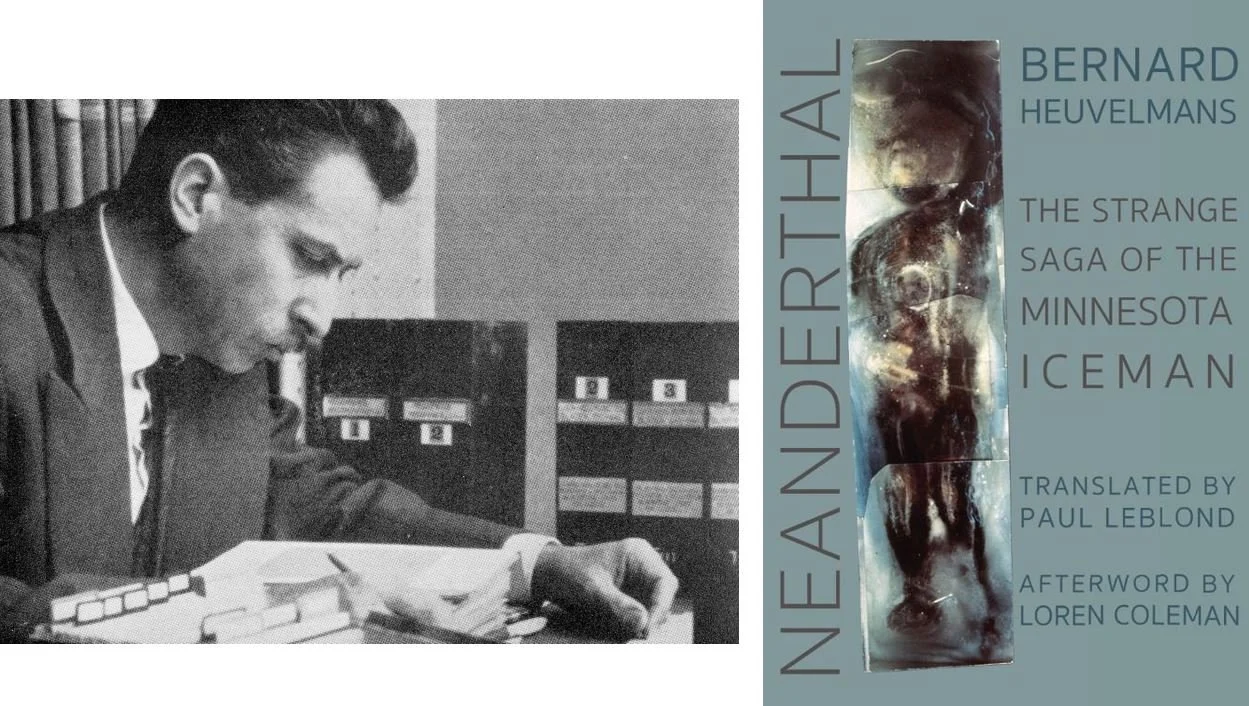

In the previous article – itself based on a section of text included in my 2016/2017 book Hunting Monsters – I mentioned the existence of a whole book devoted to the Minnesota iceman, published in 2016: Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman (Heuvelmans 2016). Neanderthal is a most curious and interesting book, and here is what I have to say about it….

Caption: cover of Heuvelmans (2016), showing the composite image that Heuvelmans assembled himself. Credit: Darren Naish.

The main story of the iceman is familiar. If you need a primer, please see the previous article. As if the initial circumstances were not suspicious enough (a travelling exhibit very clearly of the ‘Is it real? You won’t believe your eyes!’ tradition of fairground gaffs, initially marketed as the ‘Siberskoya creature’ or ‘Siberskoye creature’, and viewable for a small fee to the public), we even have the name of a person stated to have been the model-maker (Howard Ball), and know of a model (today on display at the Museum of the Weird, Austin, Texas) that most people say exactly matches their recollection of what the original looked like. As justifiable as it might be to regard the whole case as ridiculous and unworthy of scientific consideration from the off, the key factor that transformed the iceman story into an international incident (see Regal 2013) is that several knowledgeable people either became convinced that it was real, or at least became interested in the possibility that it might be.

Caption: Bernard Heuvelmans with one of the Crystal Palace pterosaur models. The photo dates to some time in the 1950s. Credit: Living Wonders Thames & Hudson Ltd; New edition edition (25 April 1983).

Among those convinced of its reality was the late ‘father of cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans (1916-2001) who, together with colleague Ivan T. Sanderson – also a formative character as goes writings on alleged mystery animals – examined the iceman in person in 1968. In 1969, Heuvelmans published a brief technical paper on the creature (it’s telling that the paper is sole-authored and not co-written with Sanderson; more on that in a moment) (Heuvelmans 1969). Even better, in 1974 he co-authored an entire book – L’Homme Néanderthal est Toujours Vivant (Neanderthal Man is Still Alive) – on the whole story. While mentioned in every published discussion of the iceman, this book (despite seeing a 2011 reprint) has long been both hard to obtain*, and untranslated from the original French.

* Like many of Heuvelmans’s works, it has become a sought-after and expensive collector’s item.

It was thus a pleasant surprise to hear in 2015 that cryptozoologist and author Loren Coleman had learnt of Paul LeBlond’s completion of a translation, and of Coleman and LeBlond’s successful venture to see said translation published in the United States.

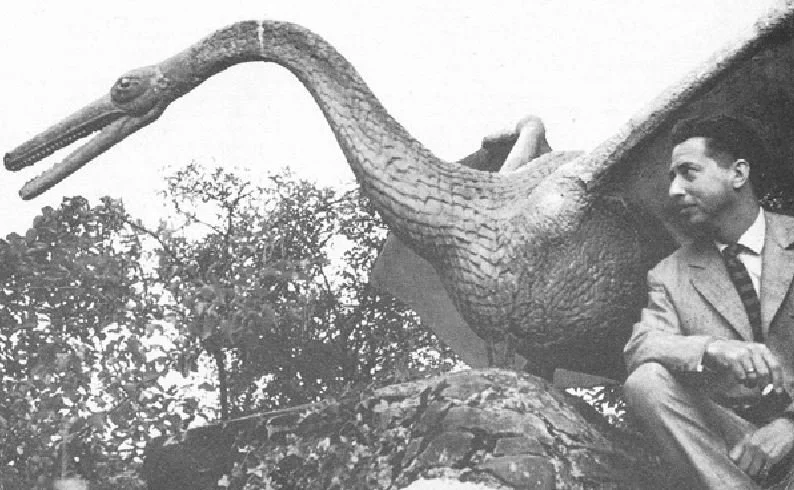

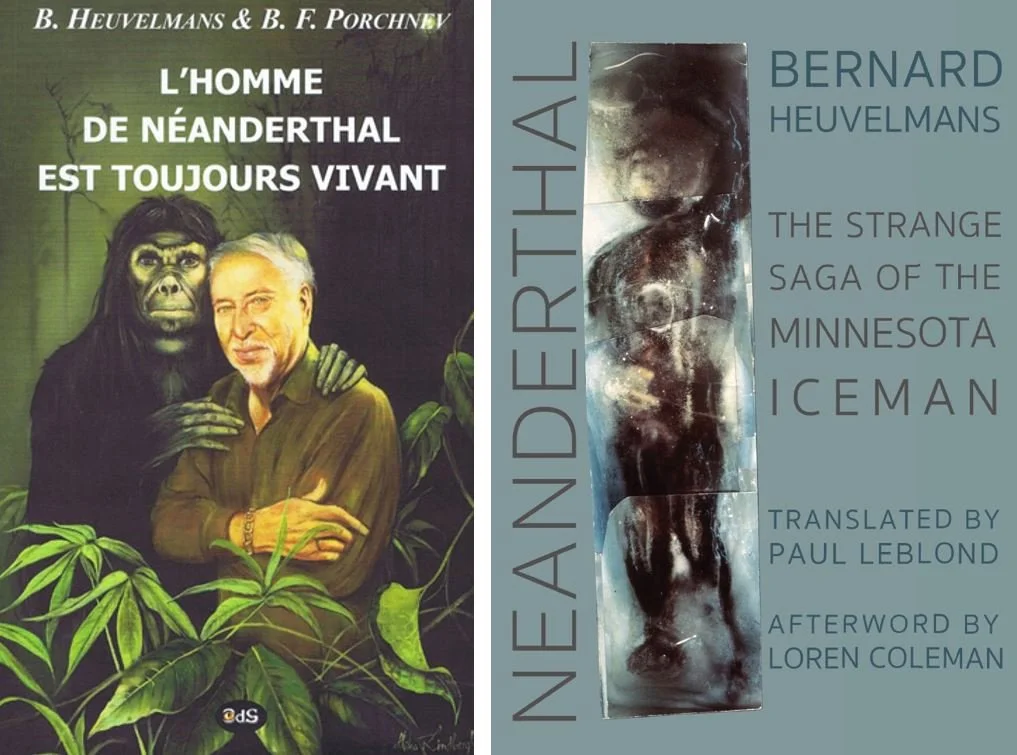

Caption: different covers of different editions. At left, the 2011 L'Oeil du Sphinx version; at right, the 2016 English translation by Anomalist Books. Credit: l'Oeil du Sphinx (left); Anomalist Books (right).

LeBlond – an oceanographer by profession but well known for his interest in sea and lake monsters (see previous Tet Zoo articles on the Cadborosaurus Wars) – had translated the volume in his own spare time. Retitled Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman (Heuvelmans 2016), the work does not include a separate section penned by Russian economist, historian and biologist Boris Porshnev, but is nonetheless very welcome. It is an inexpensive, well designed softback, and it’s most interesting – at last – to hear Heuvelmans’s full version of events.

Across 12 chapters, Heuvelmans describes all the steps in the story. It’s immediately apparent just from the titles of the chapters that he believed in a conspiracy of silence that affected his research and how it was received (there are chapters titled ‘Cloak and Dagger’ and ‘The Wall of Incredulity’). The last few chapters promise to provide his specific interpretation of the creature’s zoological and evolutionary significance (‘What it Really Was’ and ‘A History of Man-Beasts’), and it was those I was looking forward to reading the most. The book ends with a series of appendices and an afterword by Loren Coleman.

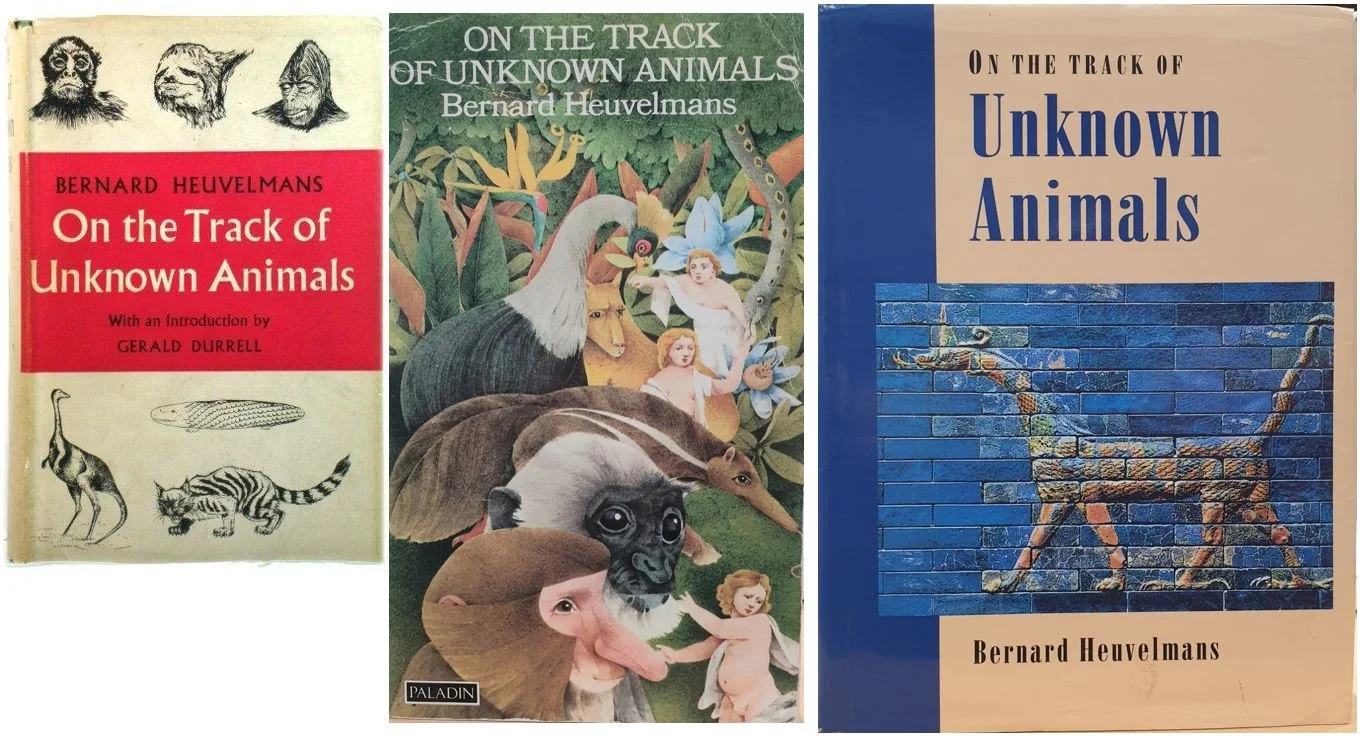

Caption: by far the best known of Bernard Heuvelmans’s books is his 1959 On the Track of Unknown Animals, republished several times and translated into many different languages. The images here show (left to right) the 1959 original, the 1965 reprint, and the 1995 edition.

Heuvelmans’s writing style is quite different from that encountered in the works most familiar to English-speaking readers (On the Track and In the Wake). He is less formal, faster-paced, angrier. It is also evident throughout the book that the whole iceman deal led to a falling-out between Heuvelmans and his friend and colleague Ivan Sanderson. Heuvelmans states on several occasions that he regarded certain of Sanderson’s statements as unwise or based on poor judgement; some of the actions concerned are well established in the public record and already noted by others as weird given that Sanderson was apparently trying to drum up official acceptance of the thing as a real carcass (Naish 2016). There are good reasons for thinking that Sanderson was playing this whole episode like a showman because, basically, that’s what he was. I’ve gradually come to the conclusion that he deliberately engaged in mystery-mongering and hype because that’s how he made a living; he was never interested in any of this stuff for honest, scientific reasons. Incidentally, Sanderson disagreed with Heuvelmans’s main premise on the iceman (that it was a Neanderthal); this disagreement is not covered in the book.

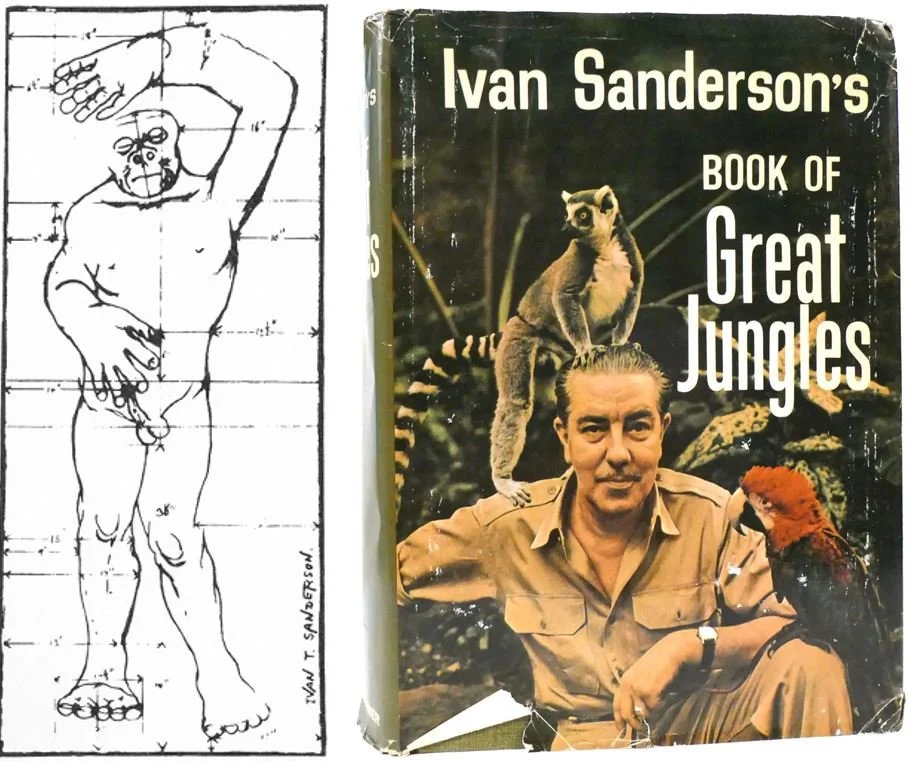

Caption: Sanderson's views on the iceman were somewhat different from those of Heuvelmans. At left, his ape-like rendition of the iceman (Heuvelmans is critical of this version in his book). At right, one of Sanderson's several books on animals and natural history. As usual, I am amazed how little imagery relevant to Ivan Sanderson (read: none) has been released online via creative commons. Credit: Ivan Sanderson (left); Ivan Sanderson's Book of Great Jungles Julian Messner, A division of Pocket Books (right).

Anatomy of a corpse, or not. One thing the book did not deliver on – to my disappointment, I regret – is the anatomy of the alleged ‘corpse’ itself. Don’t get me wrong – I don’t expect a popular book to include a heavy, technical discussion of anatomical minutiae. But I was expecting there to be a reasonable discussion of the various convincing anatomical details that Heuvelmans and Sanderson were reportedly impressed by. Instead we just get some brief references to vegetation seen stuck in the teeth, parasites on the skin and some discussion of head size and the anatomy of the hands and feet, not detailed disclosure and documentation of these features.

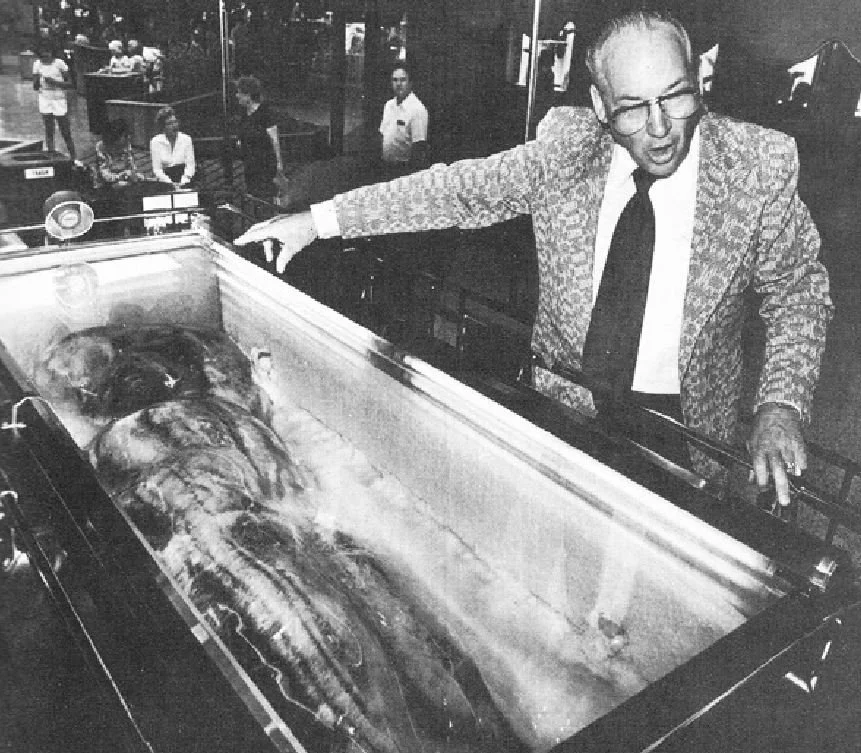

Caption: Frank Hansen – owner of the iceman – with the object itself. Credit: Costello 1984 Creatures from Elsewhere, Imprint unknown.

That the remarkable proportions of the iceman are not consistent with Heuvelmans’s argument that it represented a relict Neanderthal are explained in two ways. In some cases, the differences concerned (in skull size and overall height, for example) are put down to a continuing evolutionary trajectory not recorded in the fossil record (Heuvelmans even posits the specimen to be the result of “the final extreme result of accelerated Neanderthal evolution”).

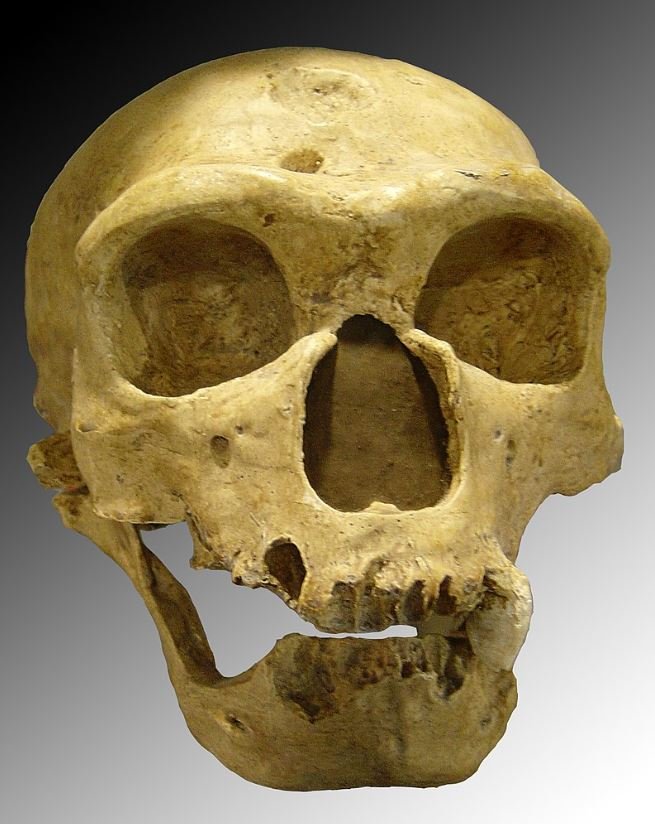

Caption: Heuvelmans's primary hypothesis was that the iceman represented a population that descended from the Neanderthals of the Pleistocene. Here is the classic La Chapelle aux Saints Neanderthal skull. Credit: Luna04 Wikimedia (CC BY-SA 3.0).

And in others (the proportionally long, slender iceman thumb: a real contrast with the Neanderthal thumb known from fossils*), Heuvelmans deliberately emphasises the minority opinions of certain scholars, positing that consensus opinion might be mistaken (he notes at least twice in the book that the iceman’s thumb is seemingly a neotenous character, an interesting hypothesis were the iceman real but one that contradicts established data on the actual Neanderthal hand). Ultimately, it’s clear – contrary to what I had always expected – that Heuvelmans did not intend this book to include the full, detailed, anatomical discussion he always promised… more on that later.

* Based on Boule’s work of the early 1900s it was long thought that Neanderthals had shorter, more massive thumbs than those of modern humans. More recent work indicates that their thumbs were, relative to the rest of the hand, proportioned much like ours (e.g., Aiello & Dean 2002, Lorenzo 2015).

Cloak and dagger. Indeed, a significant part of the story concerns the remarkable ‘cloak and dagger’ tale (to use Heuvelmans’s own words) in which it is alleged that the body was smuggled out of Vietnam via an illicit drug-trafficking route. Seeing as stories about the iceman being discovered frozen in sea ice or encountered and killed in the wild woods of Minnesota are, so Heuvelmans argues, untenable, he instead contends that the body was collected by its ward – Frank Hansen – and smuggled to the USA in a remarkable instance of complex, far-sighted enterprise. Citing the 1972 book The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia and various political acts, events and statements relevant to Vietnam, smuggling and trafficking, Heuvelmans goes as far as suggesting as the entire drug-running operation may even have originated from the specific event involving the iceman: that it established the plan that then became standard procedure in drug-smuggling operations. As interesting a tale as this is, I found it incredibly elaborate and based wholly on freewheeling speculation.

Caption: like many British people of my approximate age, one of my first introductions to the iceman was its coverage in the (somewhat credulously written) PG tips Unexplained Mysteries of the World, published in 1987. The photo of the iceman (taken by Loren Coleman) shows exposed teeth and thus looks different from the images recorded by Heuvelmans and Sanderson. Credit: Darren Naish.

To return to the anatomy of the iceman, it appears that Heuvelmans wrote a full-length monograph on the specimen, a few hundred pages long and unpublished so far as I’m aware. Given his ability to rapidly publish the initial technical paper on the iceman in an apparently sound scientific journal (Heuvelmans 1969) it is slightly surprising that he never got this grand work into print. Presumably it sits, unpublished, in the Heuvelmans archives, and presumably it explains why this book does not include the detailed anatomical data I thought it did.

Caption: portrait of Bernard Heuvelmans, here shown reviewing sea monster accounts from the Oudemans archive. Credit: Hill And Wang, 1 Jan. 1969.

Heuvelmans (2016) also describes spending an entire year working on the generation of an enormously detailed illustration of the iceman. He does acknowledge that such effort might transpire to be a waste of time, but this is because he hoped that the body would one day fall into the hands of a zoological institution, not because he considered it probable that it might be a hoax.

Caption: just in case you've forgotten, here – again – is a depiction of the iceman as it appeared (at left), and (at right) as reconstructed by Alika Lindbergh (= Monique Watteau). Images in public domain. Credit: Darren Naish.

In some of the literature denouncing Heuvelmans’ endorsement of the iceman it is proposed that he was in an especially fragile and susceptible condition during his time in the United States due to the sad and sudden death of his daughter. I had no knowledge of these circumstances prior to reading the book and was upset by the events he described: he was away from home, unable to rapidly return, and informed that his daughter had literally weeks to live. Heuvelmans (2016) argues – and I’m inclined to agree – that such personal circumstances must not be seen as relevant to his thoughts and conclusions on an alleged frozen Neanderthal. I’m not a psychologist and others who are also not should avoid making drive-by accusations of this sort.

No replacement model. A well known aspect of the iceman tale concerns the clear anatomical difference present between the object as first examined by Heuvelmans and Sanderson, and the object as observed and photographed after the furore of 1968-69. Teeth are clearly visible in the younger photographs; a contrast with the closed mouth in the Heuvelmans and Sanderson originals. The explanation offered for this discrepancy is that the original corpse was removed and hidden (either by Hansen, or by an unhappy top-tier owner, whoever that was) and then replaced by a less realistic model. The story of the ‘replacement model’ is as much a part of the iceman legend as is the discovery of the frozen corpse in the first place. However… most surprising to me was Heuvelmans’ opinion – expressed without equivocation – that there was no replacement model, and that the object said to be such was actually the original carcass, reposed after thawing and re-freezing, and ‘hidden in plain sight’. This view flatly contradicts popular cryptozoological lore in which it is widely stated that the iceman viewed by people after the Heuvelmans-Sanderson pronouncements of 1969 was a replica and not the original.

Caption: a small amount of Minnesota iceman merchandise exists. At left, we have the Jean St. Jean 2020 scale figure in one of my display cabinet, a kind gift from Loren Coleman’s International Cryptozoology Museum. At right, a t-shirt from the Museum of the Weird in Austin, a gift from John Conway. Images: Darren Naish.

Here is what Heuvelmans (2016) says: “There was only one point on which my views diverged from Sanderson’s, as well as from all others who had looked into the matter, and that was on the nature of the specimen exhibited by Hansen after April 20 (1969). I was the only one to believe that it was still the actual corpse [emphasis in the original]. True, I had a definite advantage over everyone else – I was the only one to have many excellent photos of the original exhibit … I had been sent a few color slides of Hansen’s new exhibit. After a comparison with my own, I had to agree with the evidence: it was the same and only specimen [emphasis in original].”

Moving on – what was that about “non-standard evolutionary hypotheses”? This book covers two such hypotheses and discusses them in sufficient depth to make it required reading for those interested in such things.

Caption: Neanderthals have been depicted in many different ways over the years. This illustration is by Charles Knight and dates to 1920. Credit: Charles Knight Wikimedia.

To begin with, Heuvelmans makes statements about our views on the pattern and detail of hominin evolution that I did not find objectionable. Anyone familiar with the literature on fossil hominins will be aware of arguments whereby Neanderthals can be made to look a certain way according to the bias of whomever produced the reconstruction. Heuvelmans states, and I quite agree, that our views on hominin life appearance have frequently been influenced by our own social and cultural biases, by the way in which certain species have been framed in the evolutionary narrative – hero or villain, brutish peasant or high-born – and by our expectation of what a given animal should look like within the context of the evolutionary model favoured at the time. We increasingly pride ourselves on abandonment of the erroneous ‘march of progress’ view of evolution where members of a given lineage are perceived as half-formed intermediates heading in the direction of a given goal, or where humans are considered ‘more evolved’ than other hominins, hominids and primates. Heuvelmans has quite a modern take on this issue. So far, so good.

All of this is marred, however, by a view of Neanderthals that – while undeniably interesting (a la All Yesterdays) – is surely erroneous, and I’m left wondering whether Heuvelmans developed this view only because of his hypothesis on Neanderthal survival.

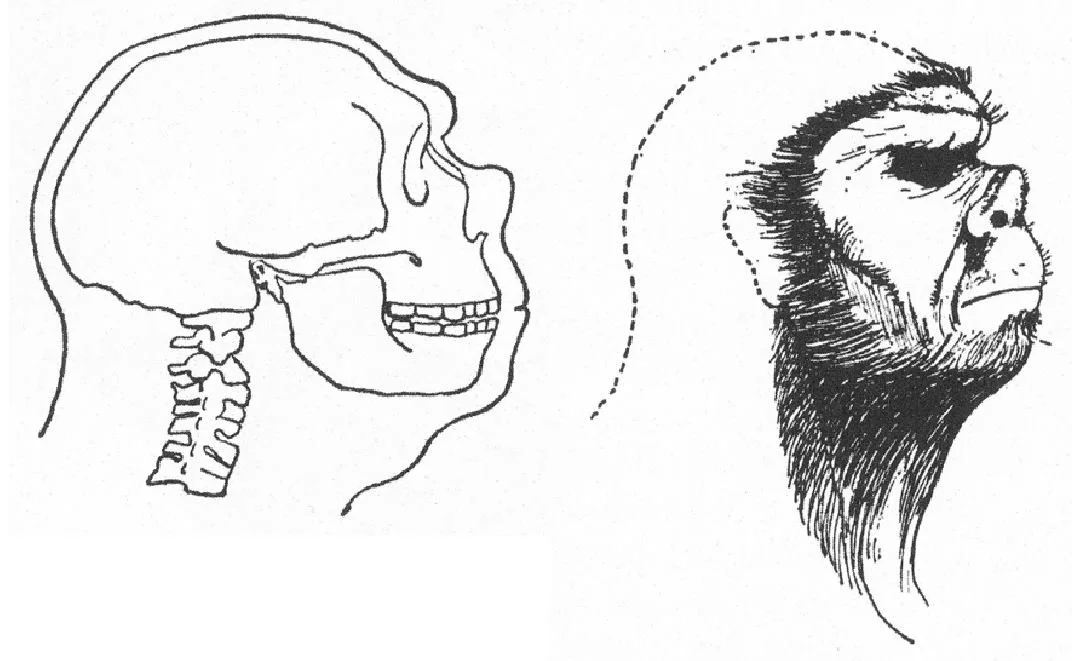

Caption: integral to the concept of pongoid man is the idea that Neanderthals ('late Neanderthals', anyway) had an elevated snub nose where the nostrils pointed forwards. At left, we see Heuvelmans' reconstruction of the La Chapelle aux Saints Neanderthal with a postulated outline. At right, a reconstruction of the iceman in profile. Credit: Heuvelmans 2016.

Neanderthals, so he explains, were likely covered by a hairy pelt (p. 173), possessed a remarkable ‘ultra-human’, upturned nose in which the nostrils pointed directly forwards (p. 179) (something like that of snub-nosed monkeys), “had no lips at all and a widely stretched mouth” (p. 180), had hands in which the thumb was both more elongate and “less readily opposable” than that of H. sapiens (pp. 182-185), had extraordinarily broad feet with curled toes that functioned in rock-climbing (p. 186), were probably capable of accruing fat stores and of indulging in a semi-hibernation (p. 211) and had “bigger eyes” that gave them “the option of vanishing into the night” (p. 211). It is also argued that Neanderthals were seen and depicted by our species as ‘beasts’ fit for hunting, extermination or even domestication as beasts of burden.

Caption: the cover of Danny Vendramini's book on the 'Neanderthal predation hypothesis'. Tetrapod Zoology does not endorse this book. Credit: Kardoorair Press.

The view of Neanderthal appearance and biology endorsed in the book is thus vaguely reminiscent of Vendramini’s notorious (and also erroneous) view in which, so it’s proposed, Neanderthals were black-skinned, big-eyed, hunchbacked uber-predators utterly unlike the sophisticated people of current mainstream palaeoanthropology. These ‘bestial’ views of Neanderthals might be jarring if new to you: as I might have said previously, they are, however, a mainstay of the cryptozoological literature (e.g., Loof-Wissowa 1994, Bayanov 1996, de Sarre 1996, Raynal 2001). To clarify, however, Heuvelmans does not promote his particular view of Neanderthals because he regards it as the typical condition for the species (unlike Vendramini): rather, he argues that Neanderthals became this way after evolving from ancestors more like H. sapiens. Let’s look at this idea in more detail…

De-hominisation. Heuvelmans’s view is that Neanderthals underwent a profound change as they abandoned material culture and took to a more ‘bestial’ way of life, the evolutionary process involved being termed de-hominisation. De-hominisation, as a supposed reverting to a more bestial form, is typically imagined as a sort of ‘de-evolution’. It is of course no such thing given the redundancy of that term: evolution means heritable change occurring across generations, it does not mean ‘evolution towards the specific form we have in mind as the best or most recently evolved’. Regardless, the de-hominisation hypothesis is a familiar trope of the cryptozoological literature, integral to the popular idea (within the cryptozoological research community) that Neanderthals have persisted as relict forms of remote, forested or mountainous regions where they avoid the attention of their cousin H. sapiens by being secretive, nocturnal and mostly solitary.

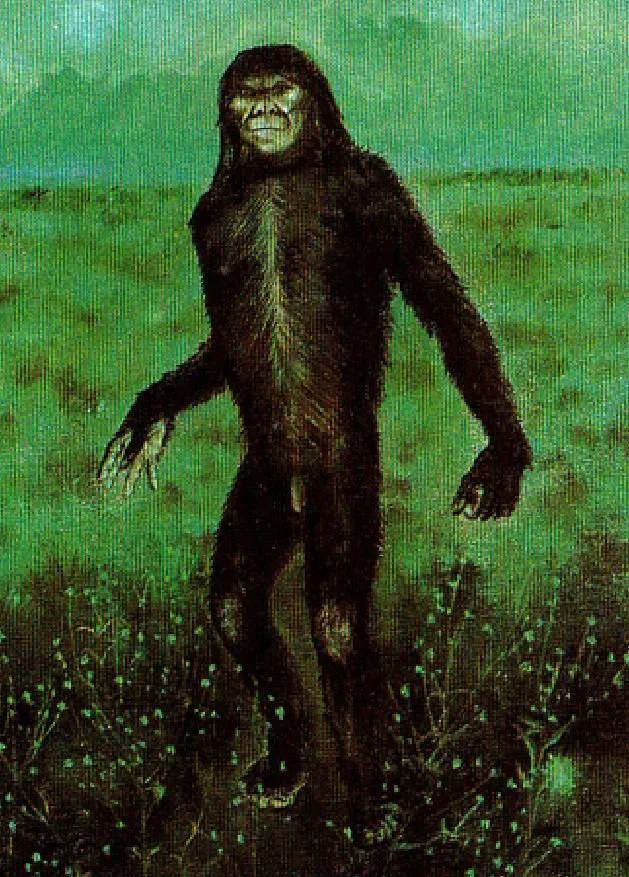

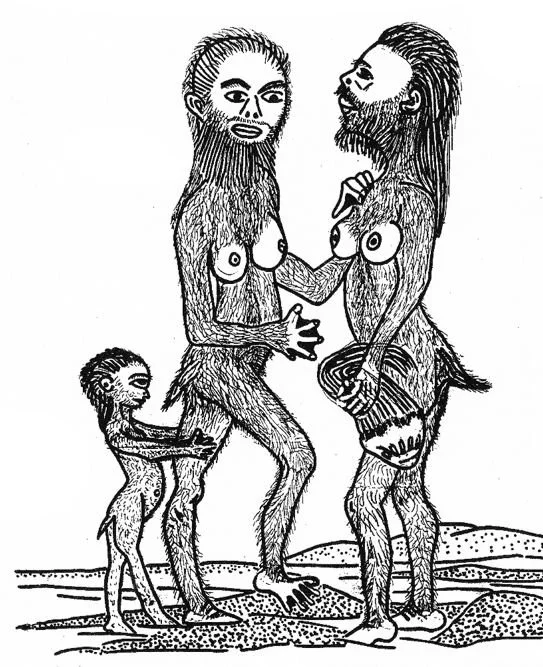

Caption: pongoid man as imagined in life by Alika Lindbergh (= Monique Watteau). The original painting features a different look for the penis and shows straggly head hair and 'ear tufts'. Credit: Creatures from Elsewhere; Imprint unknown.

The primary reason for the existence of the hypothesis is an attempted rationalisation of those abundant anecdotes and stories relating to hairy wild people across Eurasia. It never had a firm grounding, and it is like so many other evolutionary hypotheses in the cryptozoological literature in that it requires the existence of an entire new phase in evolutionary history – one involving profound ecomorphological novelty – for which we have no material evidence (Conway et al. 2013). Assuming for the moment that it might be worth taking seriously, it is – to repeat points made above – flatly at odds with everything we’ve learnt about Neanderthals in recent years. They have become more sophisticated, more technologically advanced and capable, more socially complex the more we have discovered; they might still have looked quite distinct from us but a view that they were, or were becoming, less like us over time is very much at odds with the evidence we have.

Caption: the idea that ape-type hominids evolved from human-type hominids has been put forward quite a few times in both the technical and popular literature. This New Scientist cover accompanied an article on that subject (Gribbin & Cherfas 1981). Credit: New Scientist.

Moving on, what might also surprise some are Heuvelmans’s (2016) references to evidence that hominins did not evolve from ape-like forms, but that the converse was more likely true; that anthropoid apes and humans did not descend from “some kind of archaic pongid ape like Dryopithecus. It had to be more like man than like a brachiating ape. It was probably some kind of infra-pygmy, a round-headed gnome, walking upright, in other words, the Eoanthropus imagined by leading anthropologists such as Marcellin Boule in France and Henry F. Osborn in the USA” (p. 41). The view that hominin-like proportions and posture evolved deep in hominid history – that the living non-human apes and their fossil relatives are the specialised descendants of such forms – has been revisited many times since and has at least a few modern champions. However….

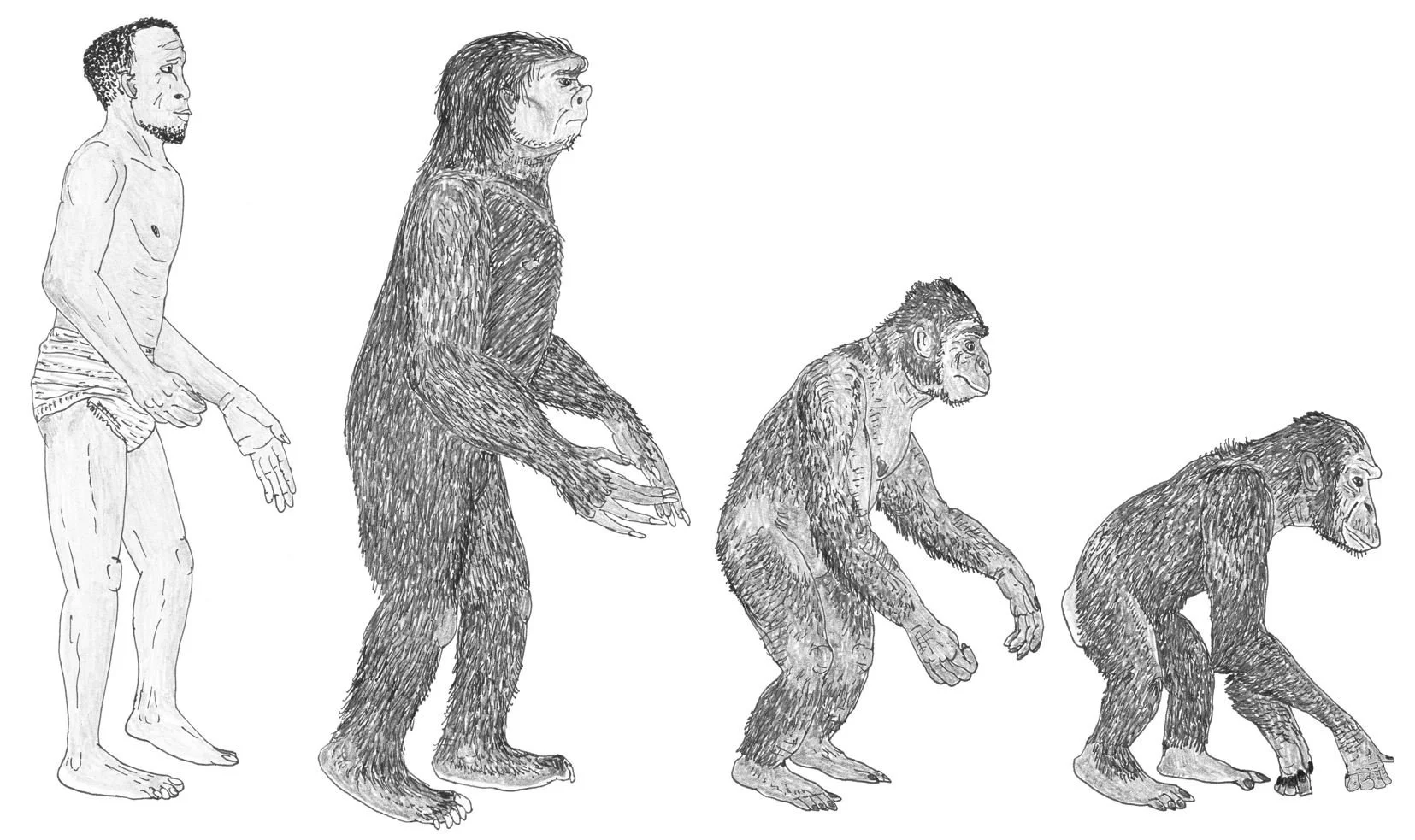

Caption: the erroneous 'march of progress' - with humans at far right - is a familiar image. Less familiar is the idea that quadrupedal hominids evolved from bipedal, human-like ones. What we see in the illustration here is, no doubt, just as erroneous as the 'march of progress', but the general trend depicted here is indeed out there in the literature. Homo pongoides – a 'bestial' hominin – is second from the left. This image is inspired by an illustration by François de Sarre. Credit: Darren Naish.

Initial Bipedalism. Long-term readers of this blog and of the arcane cryptozoological literature will recall that pongoid man is one of several icons of cryptozoology mentioned at times within the context of initial bipedalism, a hypothesis which proposes that the human body shape and habit of erect walking are not recent evolutionary innovations, but ancient ones primitive not only to hominoids or primates but perhaps to mammals and even to a far more inclusive clade of vertebrates (the model was covered here on Tet Zoo ver 2, back in 2008). The hypothesis has predominantly been promoted by ichthyologist François de Sarre whose writings have often made reference to Bernard Heuvelmans and his work (e.g., de Sarre 1996, 1997).

Indications that Heuvelmans was a proponent of this hypothesis have always been evident in his better-known works. In On the Track of Unknown Animals, there is a curious passage in the yeti chapter wherein Heuvelmans (1995) states that “man has retained the plantigrade feet of a primitive mammal … that cannot have evolved from the apes’ prehensile feet … It is the other way round: apes’ feet seem to have evolved from feet like man’s” (p. 171 of 1995 edition).

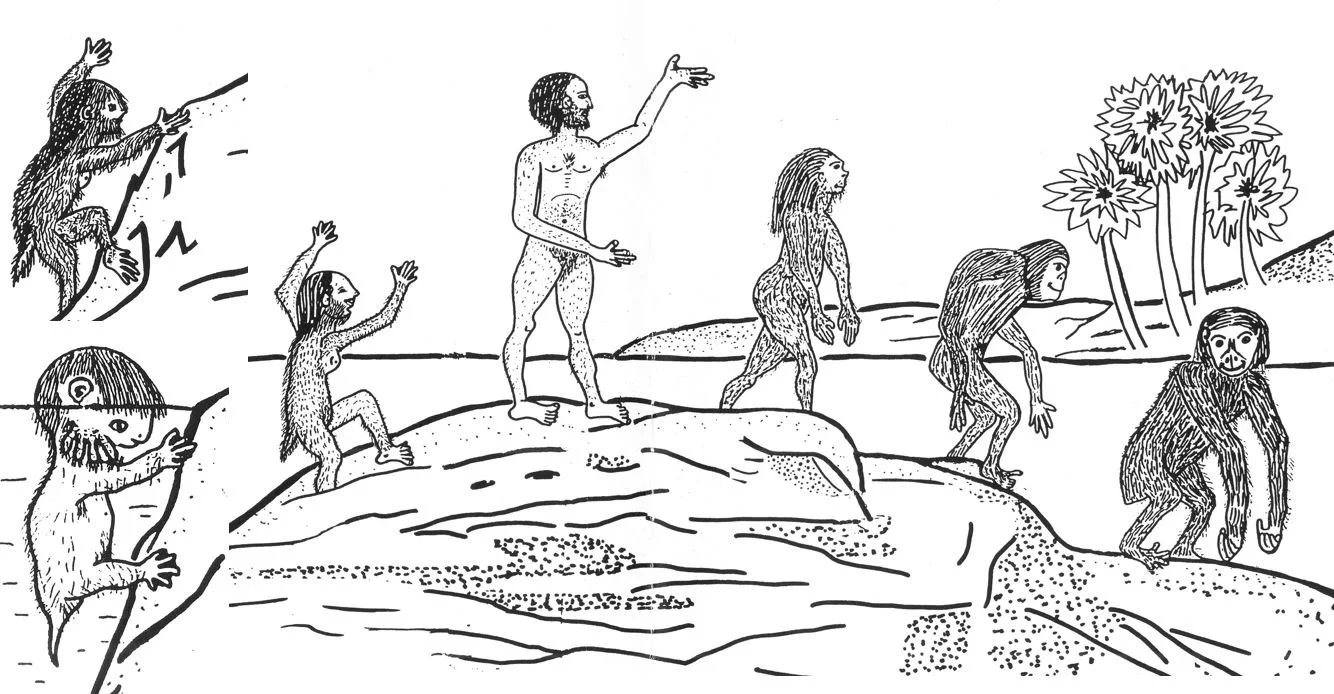

Caption: initial bipedalism posits the existence of human ancestors that look somewhat... different relative to the sort of interpretations you might be used to. This reconstruction – showing early proto-human invaders of the land – is one of my favourites. Credit: de Sarre 1997.

Neanderthal provides the full exposé, the denouement. After discussing de-hominisation, Heuvelmans (2016) states “In this work, which challenges such a solid anthropological belief as the extinction of the Neanderthals, I would have preferred not to also bring in a rather heretical theory of human origins. But that can’t be avoided. It should have been expected from the pen of a discipline of Dr. Serge Frechkop. Those who are familiar with his work are aware of my former master’s preference for non-ape theories of human origin, including those of Ranke, Kollman and Osborn, and especially Max Westernhöfer’s theory of initial bipedalism. For over thirty years I have mulled over these ideas … and find that every new discovery in paleontolology has confirmed their soundness. I am well aware that my insolence in defending these theories here will bring as many sarcasms, critiques, and even insults as my candid description of the frozen specimen of a contemporary Neanderthal” (p. 224).

Caption: this cartoon – by initial bipedalism proponent François de Sarre – depicts the idea that humans (and/or human-like animals) evolved directly from aquatic ancestors, and that ape-like primates are the specialised 'de-hominised' descendants of human-like forms. Credit: de Sarre (1997).

Final Thoughts. Neanderthal is well illustrated throughout with both black and white photos and diagrams. A colour montage depicting the iceman itself – Heuvelmans made this montage and evidently took care to avoid distortion when photographing the specimen from slightly different angles – appears on the cover. Footnotes are a mix of Heuvelmans’s own notes combined with translator notes on the various weird turns of phrase that do not translate well. A number of typos have slipped through (‘Homo abilis’ is used several times). The lack of an index is most unfortunate and makes the volume very difficult to navigate.

Also at the back of the volume is an afterword by Loren Coleman; it is essentially a personal take on his own encounters with the iceman and extensively relates the thoughts of Coleman’s late friend and colleague Mark Hall. Here there is yet more theorising and speculating about the iceman; there’s lot of talk of models being created, and even photos of the model as displayed today at the Museum of the Weird in Austin. But it’s mixed with the idea that the object was originally a genuine corpse: like Sanderson, Hall did not think that the iceman was a Neanderthal, but instead a surviving member of the erectus lineage.

Caption: Brian Regal’s 2013 book – probably the best scholarly investigation of sasquatch research out there (it is about the researchers, not the research itself) – includes documentation of the behind the scenes story on the Minnesota iceman. Credit: Palgrave Macmillan.

I regret that I did not find myself agreeing with several of the points made in this section. Firstly, for all the evidence indicating that it was a hoax all along, the text ends in open-ended fashion (“The parasites seen on the body, the vegetable matter viewed in the teeth […] all point to the Minnesota Iceman having been an actual carcass. Maybe it was”; p. 246). Secondly, the entire section endorses the viewpoint that the later (post-April 1969) images were of the supposed replacement model, Heuvelmans’s strongly worded pronouncement to the contrary being ignored. And, thirdly, Coleman implies that Heuvelmans was a victim of “the scientific establishment” in that “he never managed to stir up the interest of professional anthropologists and paleoanthropologists” (p. 246). This is patently untrue. We know that several prominent workers of the time did look into the story – John Napier at the Smithsonian among them – and even took it seriously enough to contact the FBI, eventually concluding for good reason that the object was not a real body at all (Regal 2013).

Neanderthal is a weird book. It provides the full backstory to the case from the horse’s mouth, so to speak, and elucidates the author’s favoured hypotheses on topics touched on in his other works but not previously discussed at length. Bernard Heuvelmans inhabited what many modern researchers would consider an unusual intellectual landscape. As if the promotion of almost 140 unknown animal species was not unusual enough on its own (Heuvelmans 1986), he imagined these creatures within the context of evolutionary scenarios that were decidedly heterodox and at odds with the data accepted by the majority of his peers. Indeed, this book probably provides more insight on Heuvelmans’s opinions and interpretations of evolutionary patterns than any other (the caveat being that there are several of his books that I have never read since they are yet to be translated from the original French). For these reasons the book is of great value to those interested in the history of cryptozoological thought and speculation, on arcane evolutionary hypothesising, and also potentially to those researching the history of 20th century thought on hominin evolution.

For previous articles relevant to issues discussed here, see...

The Cryptozoologicon (Volume I): here, at last, December 2014

Loxton and Prothero's Abominable Science! Origins of the Yeti, Nessie, and Other Famous Cryptids; the Tet Zoo review (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2015

If Bigfoot Were Real, June 2016

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness, August 2019

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos, August 2020

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall, October 2020

The Lake Dakataua ‘Migo’ Lake Monster Footage of 1994, February 2021

What Was the Montauk Monster? A Look Back to 2008, October 2021

Santa Cruz’s Duck-Billed Elephant Monster, Definitively Identified, November 2021

Legend of the Black Dog, August 2022

The Strange Case of the Minnesota Iceman, Part 1, August 2023

Refs - -

Aiello, L. & Dean, C. 2002. An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Bayanov, D. 1996. In the Footsteps of the Russian Snowman. Crypto-Logos, Moscow.

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume I. Irregular Books.

de Sarre, F. 1996. About the survival of relict hominoids from the point of view of a zoologist. In Downes, J. (ed) CFZ Yearbook 1996. CFZ (Exeter), pp. 98-111.

de Sarre, F. 1997. Were aquatic pre-humans the first vertebrates to enter the land? In Downes, J. (ed) The CFZ Yearbook 1997. CFZ (Exeter), pp. 142-156.

Gribbin, J. & Cherfas, J. 1981. Descent of man – or ascent of ape? New Scientist 91 (1269), 592-595.

Heuvelmans, B 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Heuvelmans, B. 1969. Note preliminaire sur un specimen conserve dans la glace, d’une forme encore inconnue d’hominide vivant Homo pongoides (sp. seu subsp. nov.). Bulletin de I’Institut Royal des Science Naturelles de Belgique 45, 1-24.

Heuvelmans, B. 1986. Annotated checklist of apparently unknown animals with which cryptozoology is concerned. Cryptozoology 5, 1-26.

Heuvelmans, B. 1995. On the Track of Unknown Animals. Kegan Paul International, London.

Loofs-Wissowa, H. 1994. The penic rectus as a marker in human palaeontology? Human Evolution 9, 343-356.

Lorenzo, C. 2015. The hand of the Neandertals: dexterous or handicapped? Journal of Anthropological Sciences 93, 181-183.

Naish, D. 2016. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Raynal, M. 2001. Jordi Magraner’s field research on the bar-manu: evidence for the authenticity of Heuvelmans’ Homo pongoides. In Heinselman, C. (ed) Hominology Special Number 1. Craig Heinselman (Francestown, New Hampshire), unpaginated.