Welcome to another article on alternative timeline dinosaurs.

Caption: what’s this? It’s an unfinished sculpt of the head of Paranthropoharpax, by Mette Aumala. Read on for more. Image: (c) Mette Aumala.

The previous two articles looked at recent and current ideas on those non-bird dinosaurs that might have evolved in alternative timelines where the end-Cretaceous extinction event never happened, and where the modern world is occupied by the descendants of groups that otherwise went extinct about 66 million years ago. You can see those articles here and here. And the most recent of those two articles looked at the ‘would there be humans anyway?’ argument, always a mainstay of alternative timeline dinosaur discussion.

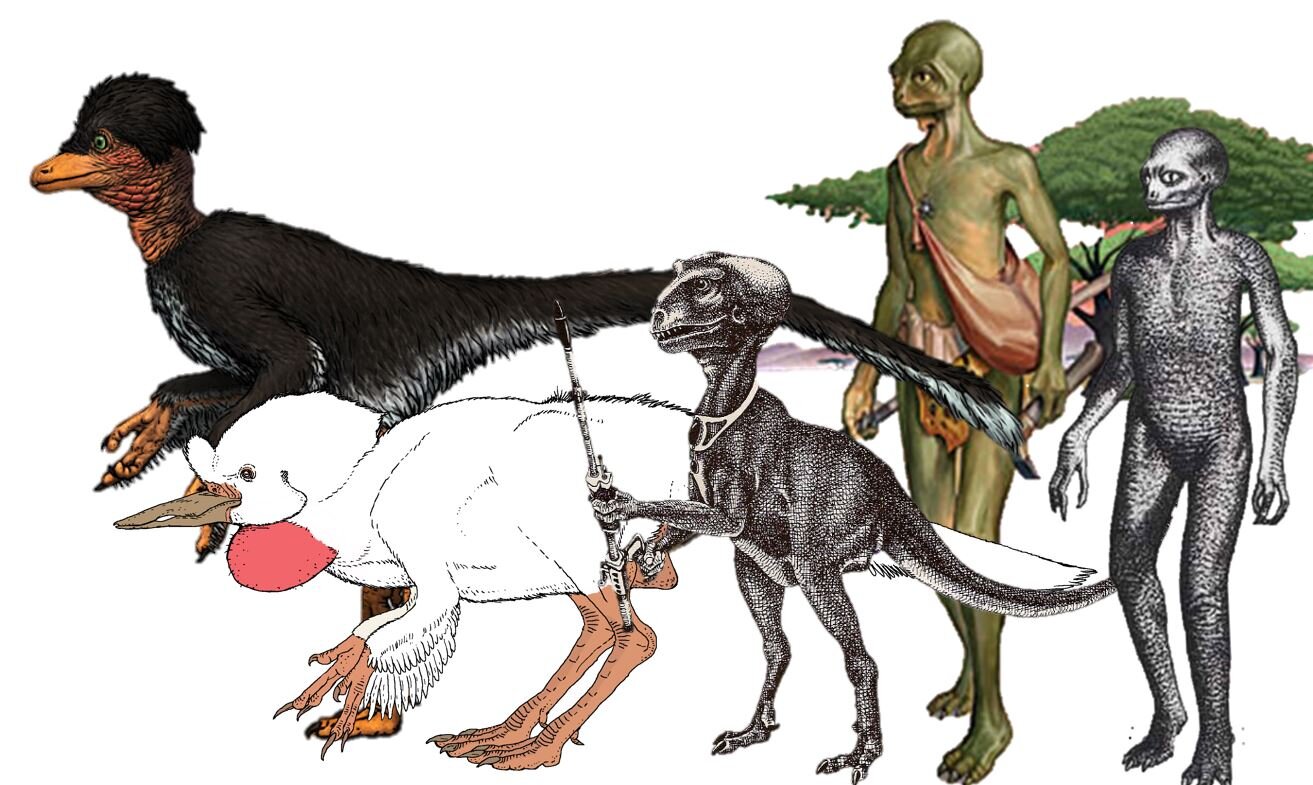

Caption: a whole bunch of dinosauroids, variously by (left to right) Mette Aumala, C. M. Kösemen, John McLoughlin, Matt Collins, John Sibbick.

The other big question that everyone asks about post-Cretaceous, alternative timeline dinosaurs is also about the evolution of intelligence, but this time of a non-human sort. If non-bird dinosaurs didn’t go extinct, surely they’d give rise to animals of primate-like, if not human-like, intelligence… right? The ‘intelligent dinosaur’ meme has been covered quite a bit here on TetZoo before (see links below), the problem as always being that my older articles on this subject are today plagued by hosting issues. For this reason I’ve linked below to the wayback machine versions of the articles concerned.

Caption: if you’ve ever opened a post-1980s dinosaur book, chances are high that you’ve seen photos of Dale Russell and Ron Séguin’s troodontid and dinosauroid models. This is the commonest set of images, as reproduced in Russell (1987, 1989) and other sources.

Conversations about big-brained dinosaurs invariably revolve – as well they should – around Dale Russell’s ‘dinosauroid’ of the 1980s, an imaginary humanoid theropod which Russell posited as a possible evolutionary descendant of troodontid theropods had they continued to evolve beyond the end of the Cretaceous. I’m keen to avoid saying too much about the dinosauroid here for fear of repeating content, but it’s worth noting that Russell’s vision of the dinosauroid was more fleshed out and detailed than many assume, and that its anatomy was more complex and nuanced than might first appear (Russell & Séguin 1982). Anyway, please read the older TetZoo articles if you want to dig deeper.

Caption: a rare photo of Dale Russell (at left) and Ron Séguin in the company of the dinosauroid; this photo belongs to the archives of the Canadian Museum of Nature and was shared in September 2019 by Jordan Mallon. Image: (c) CMN.

The dinosauroid’s infamy was and is due to the construction of an amazingly good life-sized model by sculptor Ron Séguin, who collaborated with Russell on the project (Russell & Séguin 1982). I saw the model in person in 1990 when it came to the UK for the Dinosaurs Past & Present exhibition, but failed to take the illegal photos I now so wish I had. You can read about my recollections of that amazing exhibition here (and be sure to read the comments).

Caption: Ely Kish’s dinosauroid models, used as the basis for a large painting which she finished; it remains in storage and has never seen print. These images were shared on Michael Ryan’s blog (here). Images: (c) Michael Ryan.

Séguin’s construction is well known, but a revelation new(ish) to some of us is that the late Ely Kish – another artist who collaborated with Russell (Russell 1987, 1989) – produced several amazing pieces of art that depict dinosauroids in assorted novel settings. One (a clay sculpture) shows a parent playing with a baby-faced youngster, and another – a large painting – shows a 1980s-era dinosauroid drawing attention to a reconstruction of an artistic scene. That scene is a piece of palaeoart, produced by the dinosauroids, and depicting their own kind during its cave-dwelling, ‘Palaeolithic’ phase of evolution. To my knowledge, the painting has never been published, perhaps because Dale Russell gave up on any dinosauroid-themed projects following the negative response the idea received after appearing in print during the early 80s. It was apparently produced for Russell’s 1989 book An Odyssey in Time: the Dinosaurs of North America (Russell 1989) but eventually excluded.

Caption: some post-Russell versions of the dinosauroid. At far left: a life-sized model on display at Dorchester’s Dinosaur Museum; at centre, two views of the suit made by Peter Minister for the 1991 TV series Dinosaur!; at far right, John Sibbick’s take on the dinosauroid, from David Norman’s 1985 book The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Images: Jim Limwood, CC BY 2.0 (original here), Norman (1991), John Sibbick/Norman (1985).

The dinosauroid has proved such a mainstay of post-1980s dinosaur pop-culture that it’s mentioned and discussed in a vast number of popular books on dinosaurs and prehistoric life, and has often been redrawn (often incorrectly); models and even suits worn by actors have been constructed too. One day I should compile a bibliography. And dinosauroid-like animals have been invented by several writers and authors beyond Dale Russell, among them John McLoughlin’s big-brained dromaeosaur (McLoughlin 1984), Magee’s Anthroposaurus (Magee 1993), the hadrosaurian Voth of Star Trek: Voyager, and Mette Aumala’s Paranthropoharpax naishi.

Caption: at left, John McLoughlin’s dinosauroid (which I opted to name Bioparaptor). At right: the cover of Magee’s unusual book on big-brained dinosaurs (which Amazon now values at about £200). Images: McLoughlin 1984, Magee 1993.

I still say that the dinosauroid sucks. Its entire look is dependent on the idea that the human shape is the ‘best’ one for an intelligent, big-brained animal, an idea that Russell appears to find palatable if not preferable (Russell 1987, p. 130; Psihoyos & Knoebber 1994, p. 252). But this doesn’t mean that the entire concept of big-brained smart dinosaurs is a bad one. As has now been said many times, birds (parrots and corvids, at least) overlap with primates in relative brain size and cognitive abilities, meaning not only that big-brained smart dinosaurs evolved for real in our own timeline, but also that it could happen again in a timeline where other bird-like lineages exist.

And if big-brained, smart non-bird theropods really evolved, they would – I think – more likely be shaped like birds and other theropods: not erect-bodied and humanoid, but horizontal-bodied, feathery, and with the long-snouted faces and inward-facing, clawed hands more typical of the group. This argument is old hat now since it got a lot of coverage back in 2006 when C. M. Kösemen (aka Memo) – inspired, I think, by my writings on alternative timeline smart dinosaurs – invented Avisapiens saurotheos.

Caption: for a change, I’m not going to share Memo’s Avisapiens (well, it’s already visible in the montage at top), but Mette Aumala’s Paranthropoharpax naishi. For an article on this creature go here. Mette has recently been working on a CG portraits of this species (go here on Twitter). Image (c) Mette Aumala.

In the years since 2006, Memo has invented additional big-brained hypothetical dinosaurs and – via collaboration with Simon Roy – has devised a parallel world where big-brained dinosaurs of more than one species possess their own culture, technology and art, and are depicted alongside beasts of burden and other contemporaries. Post-2006, we’ve also seen the coming and going of the 2007 kid’s TV series Dinosapien, the appearance of some surprisingly pro-dinosauroid commentary from Richard Dawkins (I wrote about that event here), and the coverage of the dinosauroid in numerous articles and books (e.g., Hecht 2007, Naish 2008, Socha 2008, Switek 2010, Losos 2017).

Caption: screengrabs of pages from two recent-ish articles discussing the dinosauroid: Hecht (2008) and Socha (2008).

And the big-brained dinosaur trope continues to raise its head in the popular and semi-technical sphere, often from people who seemingly aren’t aware of Russell’s dinosauroid and appear to be discovering it for the first time. The increasing popularity of ideas about humanoid reptilian aliens and a cryptic elite of shape-shifting lizard-people (good work, David Icke) mean that people whose idea of research starts and ends with Google are discovering dinosauroids and somehow working them into a world view that involves the Illuminati and high-level One World Government conspiracies. In short, it’s an idea that isn’t going away, and Jonathan Losos was right in saying that “… to my surprise … The dinosauroid hypothesis was alive and thriving in cyberspace” (Losos 2017, p. 323).

And that, effectively, brings us up to date…. for now. What might happen next in the world of Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs?

For previous TetZoo articles on alternative timeline dinosaurs and related issues of SpecZoo, see…

Dinosauroids revisited, November 2006

Dinosauroid cave art discovered, March 2007

How intelligent dinosaurs conquered the world, March 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Belatedly, Nemoramjetia (= Avisapiens), November 2008

Richard Dawkins and the crappy 'humanoid dinosaurs' that just won't die, November 2009

Dinosauroids revisited, revisited, October 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, June 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

TetZoo Bookshelf, February 2019, Part 1, February 2019

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 1), December 2019

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 2), December 2019

Refs - -

Hecht, J. 2007. Smartasaurus. Cosmos 15, 40-41.

McLoughlin, J. 1984. Evolutionary bioparanoia. Animal Kingdom April/May 1984, 24-30.

Naish, D. 2008. Intelligent dinosaurs. Fortean Times 239, 52-53.

Norman, D. 1991. Dinosaur! Boxtree, London.

Psihoyos, L. & Knoebber, J. 1994. Hunting Dinosaurs. Cassell, London.

Russell, D.A. & Séguin, R. 1982. Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid. Syllogeus 37, 1-43.

Socha, V. 2008. Dinosauři: hlupáci, nebo géniové? Svĕt 3/2008, 14-16.