Another belated book review! Yes, let’s look at…

The Hunt for Persisting Thylacines, an Interview

Predation and Corpse-Eating in Armadillos

The Shrews of the World

Cloudrunners and Other Cloud Rats of the Philippines

I’ve surely said on several occasions over the years that I’ve never written enough about rodents here at TetZoo. But, then, you could write about nothing BUT rodents and still not write about them enough… there are just so many of them, both in terms of numbers of species and individuals. Whatever, I’ve opted today to write about cloudrunners and other cloud rats, a group of luxuriantly furred, large, striking members of Muridae – the rat and mouse family – endemic to the Philippines.

Did Mesozoic Mammals Give Birth to Live Babies or Did They Lay Eggs?

If you know anything about mammals, you’ll know that crown-mammals – modern mammals – fall into three main groups: the viviparous marsupials and viviparous placentals (united together as therians), and the egg-laying monotremes. The fact that monotremes lay eggs is familiar to us today, but of course it was a huge surprise when first discovered. There’s a whole story there which I won’t be recounting here.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2

A few authors would have it that there are too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!): that the rich sauropod assemblage of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the continental western interior of the USA simply contains too many species, and that we need to wield the synonymy hammer and whack them down to some lower number. In this article and those that follow it, I’m going to argue that this view is naïve and misguided. You’ll need to have read Part 1 – the introduction – to make sense of what follows here. Ok, to business…

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 3

Hello faithful and noble readers. Recall the unfinished series on EXTREME CETACEANS? Today we continue with the next episode in said series.

Caption: Stenella longirostris, Phocoena dioptrica and Sousa chinensis, three of the cetacean species covered in the previous parts of this series. Image: Darren Naish.

If you don’t know what the deal is here, it’s that I’m writing about those cetaceans which I consider ‘extreme’, this meaning that they’re “weird, possessing anatomical specialisations and peculiarities that are counter-intuitive and little discussed, and most likely related to an unusual ecology, physiological regime, feeding strategy or social or sexual life”, to quote the first article in the series. And thus we get on with it…

Right whale dolphins. Many dolphin species are aesthetically pleasing because they’re of a beautifully streamlined, attenuate shape, and because they have clean, tidy colour schemes where contrasting blocks of colour are neatly separated, and sometimes augmented or marked by parallel, sweeping lines. This combination – an attenuate, streamlined form and a tidy, well-demarcated colour scheme – is carried to an extreme in the two Lissodelphis species, or right whale dolphins.

Caption: Alcide Dessalines d'Orbigny’s 1847 illustration of the Southern right whale dolphin Lissodelphis peronii. The species is named for naturalist François Peron, the first European to report a sighting of this species. Image: public domain (original here).

Right whale dolphins are mid-sized as dolphins go (about 2-3 m long), short-beaked, and incredibly attenuate. Their pectoral flippers and tail flukes are small, a dorsal fin is absent, and the tailstock tapers to a ridiculous degree. They also have the flashiest, tidiest colour scheme of black and white. They look nothing like the enormous, super-bulky right whales, but do resemble them in lacking a dorsal fin. They’re also incredibly fast, among the fastest of all cetaceans,

Caption: a Southern right whale dolphin group, photographed in 2008. These dolphins are often seen in large groups of 100 individuals or more. Image: Lieutenant Elizabeth Crapo, NOAA Corp, public domain (original here).

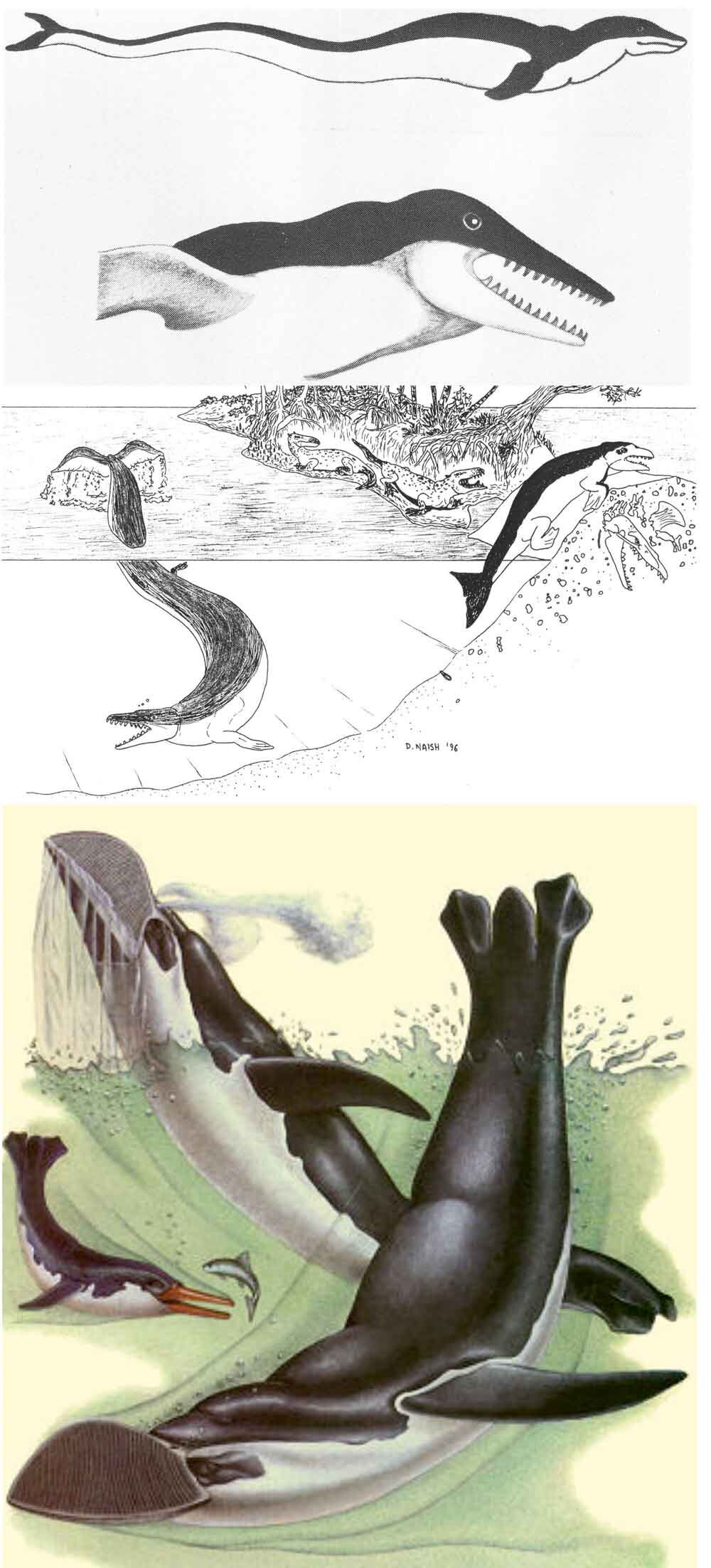

Right whale dolphins, incidentally, are close kin of lags (the Lagenorhynchus and Sagmatias dolphins) and probably of the small, short-beaked Cephalorhynchus dolphins (the most familiar of which is the piebald Commerson’s dolphin C. commersoni) (McGowen et al. 2009). But in my headcanon they’re either miniaturised, late-surviving basilosaurids, or whale-mimicking, fully aquatic penguins that have time-travelled from the Dixonian Era to the present. Look at the pictures here and you’ll see what I mean.

Caption: old depictions of basilosaurs and other archaeocetes – those at top are from McEwan (1978) and Naish (1996) – reveal that right whale dolphins are actually descendants of a lineage outside of Neoceti. Or perhaps they’re future penguins, like the Vortex (from Dixon 1981). Images: McEwan (1978) and Naish (1996), Dixon (1981).

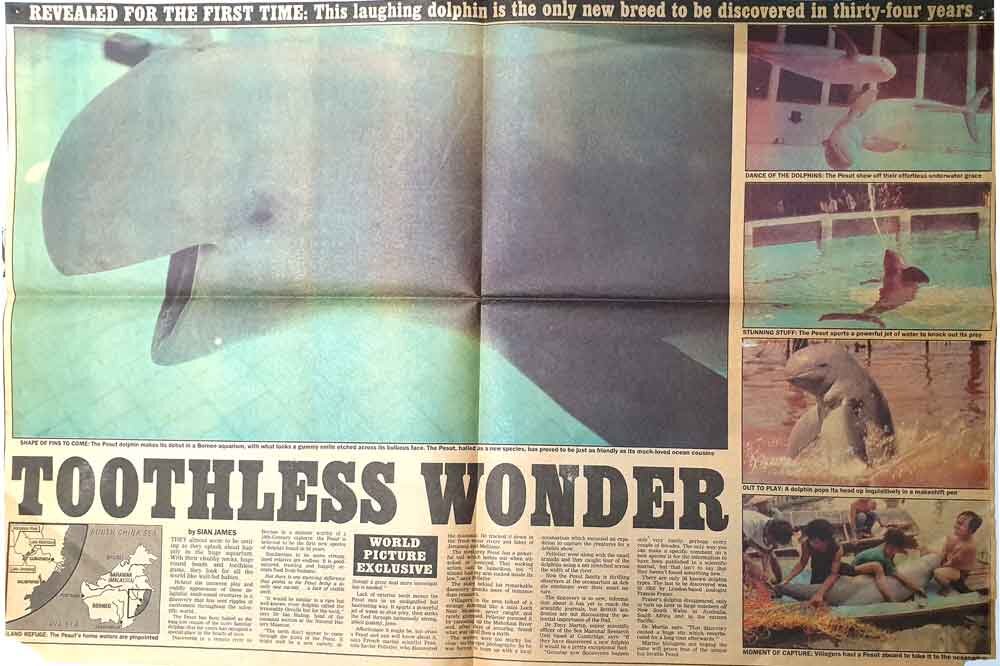

The Pesut. In 1989, I thought I knew all the extant cetacean species known to science at the time. So I was blown away when the Today newspaper, which I used to read, ran a two-page feature on a very odd cetacean which was touted as “the only new breed to be discovered in thirty-four years”, this being a reference to the number of years that had elapsed since the scientific naming of Fraser’s dolphin Lagenodelphis hosei in 1956. Evidently, the article was reporting a proposal – seemingly originating with Francois-Xavier Pelletier – in which the cetacean concerned was being considered a potential new species. Grey, toothless and prone to squirting jets of water for fun, it was said to be a freshwater inhabitant of Borneo’s Mahakam River, and was dubbed the Pesut. The what?

Caption: a Today newspaper article of 1989 reports ‘the Pesut’ as a new kind of dolphin. I regret that I don’t have the complete citation for this article; in my wisdom I clipped the date and other details at some point. Readers with exceptional memories might recognise the photo at upper right as the inspiration for a SpecZoo-themed piece of art…

Today, the Pesut isn’t regarded as a distinct species, but a local variant of the Irrawaddy dolphin Orcaella brevirostris. It’s known locally as the Pesut Mahakam, more formally as the Mahakam River dolphin, and is seemingly – with the rest of the Orcaella dolphins – an early-diverging member of the globicephaline clade (McGowen et al. 2009, Vilstrup et al. 2011), otherwise known for including killer whales, pilot whales and kin, the ‘blackfish’ [UPDATE: killer whales no longer appear to be part of Globicephalinae; see comments]. Pelletier’s proposal that the Mahakam River Orcaella population might be distinct is odd, since anyone familiar with the historical taxonomy of Orcaella knows (or should have known, even in 1989) that Pesut Mahakam is a local name for some riverine populatons of O. brevirostris (Marsh et al. 1989). Furthermore, there’s a long history of riverine Orcaella populations being considered distinct and of having their taxonomic status tested and re-evaluated.

Caption: an Irrawaddy dolphin photographed in Cambodia. Image: Stefan Brending, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

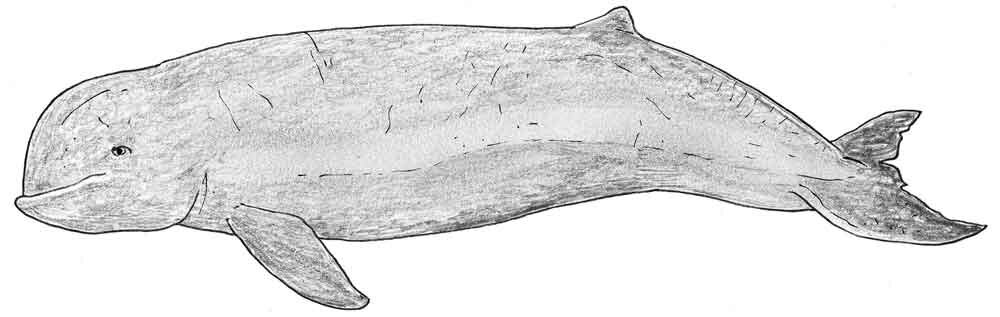

Whatever, the Pesut does look kinda unusual. Books on whales very often say or imply that the Boto or Amazon river dolphin Inia geoffrensis and Beluga Delphinapterus leucas are the only two living cetaceans with an especially mobile neck, but this very probably isn’t true and Pesuts are often shown with the head being held at an obvious angle relative to the body. Other weird features that make the Pesut ‘extreme’ are its globular, short-snouted face and smiling mouthline, and the crease that runs along part of its dorsal midline.

Caption: an effort to portray an Irrawaddy dolphin in life. This dolphin can reach 2.75 m in length, males being larger. Image: Darren Naish.

If you know anything about cetaceans you’ll be aware of the fact that the Irrawaddy dolphin is superficially similar to the Beluga, and it’s this similarity which has led to the occasional suggestion that Orcaella might not be a dolphin but a tropical member of the same family as the Beluga (Monodontidae). This isn’t a ridiculous idea, but it isn’t supported by the detailed anatomy of this animal, or by molecular data.

Caption: I said the montage would become increasingly cluttered. And we’re not done yet. Image: Darren Naish.

And that’s where we’ll end things for now; the next article in the series will appear soon. And I’ll publish a lot more on whales here in the future. Here’s some of the stuff that exists in the archives (as always, much of the material at TetZoo versions 2 and 3 has been ruined by the removal of images, so I’m linking to wayback machine versions)…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008

Scaphokogia!, July 2008

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay, August 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 1, September 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 2, September 2019

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1981. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Granada, London.

Marsh, H., Lloze, R., Heinsohn, G. E. & Kasuya, T. 1989. Irrawady dolphin Orcaella brevirostris (Gray, 1866). In Ridgway, S. H. & Harrison, R. (eds) Handbook of Marine Mammals Volume 4. Academic Press (London), pp. 101-118.

McGowen, M. R., Spaulding, M., Gatesy, J. 2009. Divergence date estimation and a comprehensive molecular tree of extant cetaceans. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 53, 891-906.

Naish, D. 1996. Ancient whales, sea serpents and nessies part 2: theorising on survival. Animals & Men 10, 13-21.

Vilstrup, J. T., Ho, S. Y., Foote, A. D., Morin, P. A., Kreb, D., Krützen, M., Parra, G. J., Robertson, K. M., de Stephanis, R., Verborgh, P., Willerslev, E., Orlando, L. & Gilbert, M. T. P. 2011. Mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses of the Delphinidae with an emphasis on the Globicephalinae. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 65.

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 2

Recall the recent article about ‘extreme cetaceans’? Well, here’s the second one in the series.

Spectacled porpoise. Porpoises – the seven* species of the delphinoid family Phocoenidae – are small, short-beaked cetaceans that mostly live fairly cryptic lives in shallow coastal seas (this description applies to the living species: some fossil porpoises were comparatively large and long-beaked). The species that typifies the group – the Harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena – is greyish (except for its white belly), has a low, triangular dorsal fin and is not especially charismatic.

* I’ve followed recent taxonomic decisions and am recognising two species within Neophocaena (N. phocaenoides and N. asiaeorientalis).

Caption: Phocoena phocoena, the archtypical member of Phocoenidae. Image: Erik Christensen, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

But other porpoises are rather different, and here we’re going to look at a far more flamboyant species, namely the Spectacled porpoise P. dioptrica of the cool and cold waters of the sub-Antarctic and Antarctic seas. This is a very poorly known species, and one of the things said about it most often is that just about nothing is known about it. It’s a 20th century discovery, its scientific debut occurring in 1912.

This species is remarkably pigmented relative to other Phocoena porpoises, being black dorsally, white ventrally, and with dark circles around its eyes. There have actually been a bunch of competing ideas on its exact appearance over the years, authors and artists disagreeing with respect to where the boundary between its dark and white areas are, what colour its flippers and tail flukes are, and so on. It’s distinct enough from the other Phocoena species that some authors have preferred to keep it in its own genus (Australophocoena), but this isn’t fashionable at the moment due to molecular data on its phylogenetic position. The suggestion has even been made that its pattern and colouring give it the ability to mimic killer whales and thus avoid predation. Cool idea, buuuut…. unlikely given that porpoises are so distinct from killer whales in size and surely in vocalisations and in the echolocatory signature that predatory cetaceans use when evaluating potential prey.

Caption: Spectacled porpoises photographed in the wild, in the Southern Ocean, in 2001. A male is at back, an adult female is closest to us, and a calf is in the middle. Image: Sekiguchi et al. (2006).

The Spectacled porpoise isn’t just remarkable for its pigmentation, however, but also for its shape, and in particular for its dorsal fin. This is ‘normal’ in some individuals, but disproportionally large – strangely so – in some individuals where it looks like an out-sized rounded flag projecting upwards and backwards at a size about twice or three times that you might predict. Like the keels, humps and unusual dorsal fins of some spinner dolphins (see the previous article in this series), this is a sexually dimorphic feature that’s especially exaggerated in mature males. Its presence is therefore presumably a sociosexual indicator of age and sexual status. Another odd thing about the dorsal fin (albeit one not unique to this species within porpoises as a whole) is that there are tiny tubercles along the leading edge (Evans et al. 2001), albeit seemingly not in all individuals. Dorsal fin tubercles are actually known for all porpoises – they’re weird and interesting and I’ll try to remember to come back to them in another article.

Caption: male, female and juvenile Spectacled porpoise, as illustrated by Uko Gorter for Natalie et al. (2018). The remarkable size of the male’s dorsal fin is obvious. Image: (c) Uko Gorter/Natalie et al. (2018).

This giant dorsal fin isn’t a newly discovered feature – it was reported and illustrated as far back as 1916 (Bruch 1916) – but it hasn’t ben commented upon as often as it might, especially given that it’s one of the most pronounced expressions of sexual dimorphism in cetaceans. Indeed, as Ellis (1983) noted, “only the killer whale manifests such a difference in the dorsal fin” (p. 198); sexual dimorphism of the dorsal fin is known in other porpoises, but isn’t as extreme as it is here (Torre et al. 2014). Apart from the fact that it’s obvious, and looks fairly absurd in the older males that have it, we don’t know much about this fin or its function. Maybe it’s ‘just’ a visual signal of sex, maturity and (perhaps) health and condition. Maybe – recall the comments in the previous article about dorsal fins functioning as thermal windows – it also plays an important physiological role. Whatever it does, it makes this an ‘extreme’ cetacean; an animal that looks surprising, weird and flamboyant.

Caption: I’m going to build a montage of the extreme cetaceans discussed in this series. This image will become more cluttered over time. Image: Darren Naish.

Finally — there’s a adoption scheme for the Spectacled porpoise. Adopt one yourself and aid in the conservation of this poorly known species.

More in this series soon. Here’s some of the stuff on cetaceans that exists in the archives (as always, much of the material at TetZoo versions 2 and 3 has been ruined by the removal of images, though remember that much or all of this is archived at Wayback Machine)…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Scaphokogia!, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015 (but now lacking all images)

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay, August 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 1, September 2019

Refs - -

Bruch, C. 1916. El macho de Phocaena dioptrica Lah. Physis, 2461-2462.

Ellis, R. 1983. Dolphins and Porpoises. Robert Hale, London.

Evans, K., Kemper, C. & Hill, M. 2001. First records of the Spectacled porpoise Phocoena dioptrica in continental Australian waters. Marine Mammal Science 17, 161-170.

Natalie, R., Goodall, P. & Brownell, R. L. 2018. Spectacled Porpoise. In Würsig, B., Thewissen, J B. M. & Kovacs, K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Academic Press, pp. 912-916.

Sekiguchi, K., Olavarría, C., Morse, L., Olson, P., Ensor, P., Matsuoka, K., Pitman, R., Findlay, K. & Gorter, U. 2006. The spectacled porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica) in Antarctic waters. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management 8, 265-271.

Torre, J., Vidal, O. & Brownell, R. L. 2014. Sexual dimorphism and developmental patterns in the external morphology of the vaquita, Phocoena sinus. Marine Mammal Science 30, 1285-1296.

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 1

It was while going through my read all the books on the whales of the world phase of the early 1990s, I remember, that I first read of the dolphins – members of the highly streamlined, long-beaked, oceanic dolphin group no less – that have such weird features as deep keels, humps on the back and tailstock, and non-streamlined, forward-canted dorsal fins. Yes, we all know that whales are streamlined, torpedo-shaped animals with sensibly shaped appendages, but they’re not all like this. Quite a few species are weird, possessing anatomical specialisations and peculiarities that are counter-intuitive and little discussed, and most likely related to an unusual ecology, physiological regime, feeding strategy or social or sexual life.

Caption: a nice, normal looking group of Spinner dolphins. The obvious dark cape and paler side regions make these look like Hawaiian spinners but they were apparently photographed in the Red Sea. Image: Alexander Vasenin, CC BY-SA 3.0, wikipedia (original here).

In this short series of articles – yeah, this is Part 1 – I want to talk about just a few such animals, and I hope you’ll be as surprised by their anatomy and specialisations as I was when I first learnt about them.

Extreme spinners. Everybody knows that dolphins are streamlined, and the oceanic long-beaked dolphins (those conventionally united in the genus Stenella) are streamlined the most. The Spinner S. longirostris – a species that occurs throughout the tropical and subtropical marine waters of the world – is one such animal, its very long beak, torpedo-shaped body and tailstock and well-proportioned fins all appearing like textbook adaptations for swift movement in the pelagic environment. Yet for all this, some spinner dolphins – some specific individuals belonging to some specific populations – are very odd indeed.

Caption: one of the very best depictions of an ‘extreme’ male Eastern spinner is this one, from Shirahai & Jarrett’s 2006 Whales, Dolphins and Seals. Image: (c) Brett Jarrett.

These animals have arching dorsal humps and massive, bulbous ventral convexities on the tailstock which give them a peculiarly asymmetrical, lumpy appearance, the dorsal fin is not recurved and falcate, but has a straight or even concave anterior margin such that it might even lean forwards, and the tail flukes turn upwards at their outer edges. The exaggerated lump on the lower surface of the tailstock has a name: it’s the post-anal hump. This structure isn’t unique to the Spinner but is also present in other delphinids, like the Delphinus species. It appears to be sexually dimorphic and is especially prominent in mature males (Ngqulana et al. 2017). Perrin & Mesnick (2003) argued that these features - which are variable in spinner populations and most strongly developed in the so-called Eastern and Whitebelly spinners - are linked to testis size and to a polygynous mating system where males need to be highly distinct from their many female consorts, and built to display against, and fight with, other males. In other words, the most ‘extreme’ spinners are the most polygynous.

Caption: adult males differ in appearance across spinner populations, and it seems that the most ‘extreme’ males are those from the most polygynous populations. This diagram (from Perrin & Mesnick 2003) shows - from top to bottom - male Hawaiian, Eastern and ‘whitebelly’ spinners. Image: Perrin & Mesnick (2003).

How and why might this remarkable feature have originated? Spinners and other cetaceans adopt a sinuous, vaguely S-shaped profile when displaying to one another (this has now been seen in diverse cetaceans, mysticetes as well as odontocetes; Helweg et al. 1992, Horback et al. 2010), and one suggestion is that the post-anal hump and a matching convexity on the dorsal surface of the tailstock might serve to accentuate the curves of the S and thereby function in exaggerating this signal. One idea about the S-shaped pose is that it functions in shark mimicry (Norris et al. 1985; some sharks also adopt an S-shaped profile and use it to signal aggressive intentions), but the fact that it’s as widespread in cetaceans as it is – and similar poses are seen in other aquatic vertebrates – indicates that any similarities with non-cetaceans are convergent.

Caption: S-shaped postures, depicted (sometimes schematically) in cetaceans of very different sizes and proportions, from Horback et al. (2010). (A) Spinner dolphin, (B) Beluga, (C) Humpback whale. Evolve dorsal and ventral convexities on the body and tailstock, and you can exaggerate the intensity of this signal. Image: Horback et al. (2010).

Anyway… the features discussed here appear intuitively odd because they’re just about the opposite of what you’d predict to be present in a fast-swimming, pelagic predator which has otherwise evolved to be ultra-streamlined. But there you are.

Caption: humpback dolphins are not especially well known, and even less well known is that they’re kept in captivity in a few places and have been trained to do tricks. This individual was photographed in captivity in Singapore. Image: Tolomea, CC BY 2.0, wikipedia (original here).

The humpback dolphins. Everyone’s heard of the Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae, but less well known is that there are dolphins with humps too, perhaps four species of them if you follow some studies of molecular variation within the group (the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin Sousa chinensis, Australian humpback dolphin S. sahulensis, Atlantic humpback dolphin S. teuszii and Indian Ocean humpback dolphin S. plumbea). Superficially, Sousa dolphins look something like bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops), and like them they’re coastal animals that prey on diverse fishes and cephalopods. Unlike the Tursiops dolphins, the Sousa species have a long raised section – sitting dorsal to the neural spines and musculature of the back – that extends along the middle part of the dorsal surface. The dorsal fin sits on top of this hump.

Caption: comparatively few people know that there are dolphins with humps, but check it out. These are Tom Ritchie’s illustrations of Sousa dolphins, representing adult males identified by Watson (1981) as S. chinensis (above) and S. teuszii (below). Images: Watson 1981.

The function of this hump – if it has one – is not well studied and authors have mostly avoided mentioning the possibility that it might have one. Does it function as a visual or acoustic signal of maturity? Does it have some role in buoyancy, hydrodynamics or streamlining? Is it a fat store? The dorsal fins of at least some cetaceans appear to function as so-called thermal windows: as heat-dumping structures, the large and extensive blood vessels of which carry cooled blood to the body interior (Meagher et al. 2002). In males, this cool blood helps lower the temperature of the deeply internal testes (Pabst et al. 1995), which might otherwise be prone to overheating. The humps of humpbacked dolphins, like the dorsal fins, appear to be richly innervated with blood vessels which again transport cooled blood from the animal’s exterior surface to deep within its body (Plön et al. 2018).

Caption: (A) vasculature in the dorsal fin and hump of a humpback dolphin compared with (B) dorsal fin vasculature in a Tursiops dolphin. The blood vessels in Tursiops are proportionally larger, but there’s a great number of them in the humpback dolphin, thanks to the hump. Image: Plön et al. 2018.

Could the hump therefore be a thermoregulatory specialisation for this mostly tropical group? Further research is needed, but this could be consistent with the fact that the hump is proportionally largest in adult males, and perhaps proportionally largest in those populations that inhabit the most tropical parts of Sousa’s entire range. A hydrodynamic role for the hump remains plausible but has yet to be investigated (Plön et al. 2018).

And that’s where we’ll end things for now. More in this series soon. I’ll publish a lot more on whales here in the future, but here’s some of the stuff that exists in the archives (as always, much of the material at TetZoo versions 2 and 3 has been ruined by the removal of images)…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Scaphokogia!, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015 (but now lacking all images)

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay, August 2019

Refs - -

Helweg, D. A., Bauer, G. B. & Herman, L. M. 1992. Observations of an S-shaped posture in humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Aquatic Mammals 18.3, 74-78.

Horback, K. M., Friedman, W. R. & Johnson, C. M. 2010. The occurrence and context of S-posture display by captive belugas (Delphinapterus leucas). International Journal of Comparative Psychology 23, 689-700.

Meagher, E. M., McLellan, W. A., Westgate, A. J., Wells, R. S., Frierson, D. Jr. & Pabst, D. A.. 2002. The relationship between heat flow and vasculature in the dorsal fin of wild bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus. Journal of Experimental Biology 205, 3475-3486.

Pabst, D. A., Rommel, S. A., McLellan, W. A., Williams, T. M. & Rowles, T. K. 1995. Thermoregulation of the intra-abdominal testes of the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) during exercise. Journal of Experimental Biology 198, 221-226.

Norris, K. S., Wursig, B., Wells, R. S., Wursig, M., Brownlee, S. M., Johnson, C. & Solow, J. 1985. Behavior of the Hawaiian spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris. National Marine Fisheries Service Administrative Report LJ-85-06C.

Ngqulana, S. G., Hofmeyr, G. J. G. & Plön, S. 2017. Sexual dimorphism in long-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus capensis) from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of Mammalogy 98, 1389-1399.

Perrin, W. F. & Mesnick, S. L. 2003. Sexual ecology of the Spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris: geographic variation in mating system. Marine Mammal Science 19, 462-483.

Plön, S., Frainer, G., Wedderburn-Maxwell, A., Cliff, G. & Huggenberger, S. 2018. Dorsal fin and hump vascular anatomy in the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa plumbea) and the Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops aduncus). Marine Mammal Science 35, 684-695.

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay

Back in July 2019, myself and a bunch of friends stepped aboard the Pont-Aven for several days of sea-watching in the Bay of Biscay. We were to travel from Plymouth (UK) to Santander (Spain), the event being organised by ORCA, a charity that monitors whales and uses the data for conservation purposes (they’re here on Twitter). ORCA uses cruise liners, ferries and other vehicles as whale-watching platforms. Nigel Marven was a special guest on our trip and it was great to catch up with him.

Caption: our vessel of choice - the Pont-Aven - at port in Santander, Spain. I cannot tell you how much trouble I went to to get to this ship before departure time. I very nearly didn’t make it. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: the man, the legend; Nigel Marven.

The purpose, of course, was to see whales. The weather was outstandingly good (meaning that I got burnt), but so was the whale watching: I’m pleased to say that we saw literally hundreds of animals of seven or eight species, as you can see from the photos below. My own photos are not great since my camera isn’t exactly the best for fast-moving, far-away animals like whales, so those you see here were mostly taken by my trusty pal Alex Srdic (who’s here on Instagram and here on Twitter). Thanks, Alex.

Caption: several cetaceans have extremely complex markings allowing them to be identified to species and even population. Individuals can be recognised on the basis of their markings too. Image: Alex Srdic.

The Bay of Biscay is a world-famous whale-watching hotspot, famous in particular for Cuvier’s beaked whales Ziphius cavirostris and Sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus. Dolphins of several species are a frequent sight too, as are rorquals of a few species, Harbour porpoise Phocoena phocoena and pilot whales. A very lucky whale-watcher might get to see Blue whale Balaenoptera musculus, Killer whale Orcinus orca or True’s beaked whale Mesoplodon mirus. In fact, something like 30 species have been recorded in the region. This is phenomenal and mean that it’s theoretically possible for several species of some of the most elusive whale groups – like beaked whales and globicephaline dolphins – to be seen within days or weeks of each other.

Caption: in good weather, the blow of a big whale (like a Fin whale - as here - or a Sperm whale) is visible from great distance, and in the case of these two species can be diagnostic. Image: Alex Srdic.

Caption: a dynamic leap by a Striped dolphin. Dolphins of some species appear to be attracted to ships and even to deliberately show off when they get close to them. Image: Alex Srdic.

Why is the Bay of Biscay so good for whales? It’s mostly because the topography is complex, combining large, shallow shelf regions, steep sections of shelf edge – sometimes with impressive slopes and deep, enormous rocky canyons twice as big as the Grand Canyon – and a deep abyssal plain section (Carwardine 2016). Depth varies from 1.7 to over 4.7 km. This variation – combined with the overall productivity of the region and its position relative to the Atlantic and English Channel – means that there’s the chance to see continental shelf species (like porpoises), those that use deep canyons and other shelf-edge habitats (like beaked whales) and true oceanic deep-divers that forage in the deepest waters (like sperm whales).

Caption: back and dorsal fin of a Fin whale, remnants of the blow still hanging in the air. Image: Alex Srdic.

As it happens, we were extraordinarily lucky. Fin whales B. physalus are regular animals of the area, and we had amazing, relatively close views of them (by ‘close’, I mean perhaps 30 m from the ship, not alongside the vessel). Fin whales – the second largest extant animal after the Blue – have a blow that’s visible on the horizon and is about 8 m tall. The blow hangs in the air for a surprising time. One of the most remarkable things about the Fin whale is its asymmetrical pigmentation: the right side of the face is marked with a large pale area, as is the right side’s baleen. There are some old TetZoo articles on what this might mean and how it might function – see the links below.

Caption: excellent view of the splashguard - the conical structure surrounding and ahead of the blowholes - and paired blowholes of a surfacing Fin whale. Despite its name, the dorsal fin of the Fin whale is smaller and blunter than that of some other rorquals. Image: Alex Srdic.

Two coastal species were seen early on in our trip: Harbour porpoise and Common bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus, though I don’t have good photos of either. The majority of dolphins seen on our trip (as is typical for Biscay whale watching) were Short-beaked common dolphin Delphinus delphis, which were sometimes seen in groups of more than ten. Their distinctive hourglass markings are always visible when they leap – which they often do, sometimes while immediately adjacent to a ship – and we also got to see calves on one or two occasions.

Caption: here’s the whole-body view of the common dolphin shown in detail above. This individual only has one stripe extending from the beak to the flipper, with a large pale area separating the eye and flipper. Different configurations are present in different populations. Image: Alex Srdic.

Caption: as the light begins to fade during the later part of the day, a group of Short-beaked common dolphin carve through a surging wave. Note the calf close to the adult at upper right. Image: Alex Srdic.

We also had excellent views of Striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba. They behaved in characteristic acrobatic fashion, leaping high out of the water, making impressive splashes and jumping in the ship’s wake. They typically make a lot more disturbance at the water’s surface than do common dolphins, creating great bursts of spray and rooster-tail patterns when they leap and surge. Striped dolphins are near-globally distributed. They’ve been the source of discussion lately since it’s recently been shown that the Clymene dolphin S. clymene is a naturally occurring hybrid between this species and the Spinner S. longirostris (Amaral et al. 2014).

Caption: we had many excellent views of high-leaping Striped dolphin. Note how much spray and splashing is associated with the leaping of this species. Image: Alex Srdic.

Finally as goes dolphins, we also saw pilot whales, identified on the basis of their black colouration and strongly backswept dorsal fins. These were most likely Long-finned pilots Globicephala melas (it’s more typical of temperate and cold waters than the Short-finned G. macrorhynchus) but we didn’t see any of the key features that allow the two species to be distinguished, and none of our photos are good enough to warrant sharing. A mysterious whale was seen among the pilot whales. It seemed to be very dark and with a short, blunt-tipped, parallel-sided but only weakly curved dorsal fin; I don’t think that its head was seen but I had the impression that it was a shallower-bodied animal than the pilot whales. Several different views were offered on its identity with the most likely (on the basis of dorsal fin shape) being that it was perhaps a False killer whale Pseudorca crassidens. That’s not tremendously likely but not impossible.

The whale most famously associated with the Bay of Biscay is Cuvier’s beaked whale, seen so frequently in the area that it’s regarded as the premier location for sightings of this species, worldwide. I don’t know if you’re guaranteed a sighting of a Cuvier’s while there, but – whatever – we were lucky, since we saw nearly 20 of them, ranging from smooth, clean-bodied youngsters to heavily scarred males.

Caption: Cuvier’s beaked whale, seen relatively close to the ship. Image: Alex Srdic.

Caption: heavily scarred Cuvier’s beaked whale, seen at distance and only briefly. We didn’t see any other individuals with scarring as impressive as this. Image: Alex Srdic.

Some individuals have markedly pale heads sharply demarcated from the rest of the body, others do not. On occasion, one or two individuals were close enough to the ship that I was able to get a half-decent shot with my mobile phone. Each sighting was a huge thrill. While we were oh so lucky as goes Cuvier’s, we didn’t see sperm whale, alas. We also saw Northern minke B. acutorostrata on perhaps two occasions, though again I don’t have any good photos.

Caption: another plus… amazing sunsets, and sunrises too. Image: Darren Naish.

Finally, we didn’t just see whales. The same route is also great for seabirds, and we also saw such fishes as tunas and sunfishes. As much as I’d like to start talking about the birds, I’m out of time. Anyway – the trip was excellent: rewarding, fun, and educational. I’ll definitely be doing it again. You should consider supporting ORCA and their work as well.

Cetaceans have been covered at length on TetZoo before - mostly at ver 2 and ver 3 - but these articles are now all but useless since all of their images have been removed (and/or they’re paywalled, thanks SciAm). Over time, I aim to build up a large number of cetacean-themed articles here at ver 4.

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Scaphokogia!, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015 (but now lacking all images)

Refs - -

Five Famous Palaeolithic Rock Art Enigmas

I’m fascinated by ancient rock art and have written about it a few times here at TetZoo…

… in part because it often gives us a great deal of useful information on the life appearance of extinct Pleistocene animals. My article on the life appearance of the Woolly rhino is here, the one on Pleistocene horses is here, and the one on Megaloceros is here. As per usual, at least some of these articles have been ruined by hosting issues (if you’re patient, they’ll eventually appear in one of the Tetrapod Zoology books – which are a thing, I promise).

Today I want to talk about a few examples of Palaeolithic art that have caused controversy and uncertainty as goes what they depict. I’ve been unashamedly hokey and sensational with regard to which I’ve chosen, and have deliberately picked cases where especially odd things have been said about them, often in decidedly grey literature. This doesn’t mean that I endorse said odd things, but they’re certainly relevant and inspirational to my interests. Furthermore, they aren’t so much ‘enigmas’ as ‘ambiguous cases open to interpretation’.

I should also emphasise that I’m concentrating here on European rock art. Australian, African, Asian and North American rock art also has its fair share of intriguing images that have been the topic of contention.

Caption: the famous Lascaux ‘unicorn’ or ‘licorne’. Pretty weird that an animal with two horns ever became a ‘unicorn’, but whatevs. Credit: New Cryptozoology Tarmola Wiki (original here).

1. The Unicorn of Lascaux. Among the most famous of enigmatic rock art animal depictions is the bovid-like, horned quadruped from the ‘Hall of the Bulls’ at Lascaux, Dordogne, France, sometimes called the licorne. It’s 1.65 metres long and combines a dark, rectangular muzzle and shoulder hump with a sway back, rotund belly (leading some to suggest that it might be pregnant), short tail and dark legs. Large dark reddish blotches with pale centres cover its sides. Its most memorable feature is its two long, parallel, straight horns, which project forwards and upwards from its forehead in a manner that doesn’t really match any known animal. The fact that there are clearly two horns means that ‘unicorn’ is a total misnomer, but I guess we’re stuck with it.

Caption: the ‘unicorn’ (at far left) in the Hall of the Bulls, Lascaux Cave. Image: N. Aujoulat © MCC-CNP, from Martin-Sanchez et al. (2015).

The animal is standing at the far left of a frieze that features horses, aurochs and deer – among the best examples of their kind, in fact. The realism of the two aurochs in the same frieze is intriguing, since this somehow adds credence to the ‘unicorn’: surely it must be a realistic depiction of something real as well? Needless to say, it doesn’t match anything known to science. Is this a representation of a species otherwise unknown, it is a ‘bad’ depiction of a known species, or is it a fictional, symbolic or representational animal of some sort? Well, people have suggested a bunch of ideas.

Caption: could the ‘unicorn’ be a Chiru? I dunno, it doesn’t seem like a good match. Image: Philip Sclater, public domain (original here).

A few informal suggestions have drawn attention to the supposed cat-like form of this animal (err, not sure I see that myself… what would this mean – that it’s a bovid-mimicking horned cat? Bwahahaaaha), or the possibility that it might depict people wearing a skin as a hunting disguise (nice idea, but no way to be at all confident about it) (Eberhart 2002). The best known idea – “best known” because it was mentioned in Björn Kurtén’s Pleistocene Mammals of Europe – is probably Dorothea Bate’s that it depicts a Chiru Panthalops hodgsoni (Kurtén 1968). While there’s a really vague superficial resemblance, the spotted body and forward-canted horns of the ‘unicorn’ aren’t at all Chiru-like. The suggestion that it might be saiga is out there too, but this suffers from the same problems: the horns are the wrong shape, what’s with the spotting, and why are the key features of saiga (most notably the distinctive snout) missing?

Caption: Björn Kurtén’s Pleistocene Mammals of Europe features this composite, showing the ‘unicorn’ next to a Chiru, the idea being that they look quite similar. But I think the picture is a bit of a cheat since Chiru horns point upwards and backwards, not forwards. Image: Kurtén (1968).

2. The Sorcerer of Trois Frères. I can’t not talk about the famous ‘deer man’ of Trois Frères, Ariège, France, even though it almost certainly isn’t a depiction of a non-human (reminder: TetZoo isn’t just about non-human tetrapods). This image is 75 cm long, and is most typically imagined as an illustration (it combines both engraving and paint) of a bipedal male humanoid, standing with partly folded, short forelimbs, and with a low shoulder hump, short neck, small-eyed, bearded face, erect, deer-like ears and stout branched antlers. A curving tail and dangling male genitals are supposed to be visible as well, and prominent dark stripes run the length of the body and hindlimbs. Could this be a god-like creature believed in as a protector or object of worship? Or does it show that the artist was part of a group who believed in human-non-human transmogrification or transmutation? Is it a therianthrope (a mashup of human and non-human body parts of the sort illustrated elsewhere in the ancient world)? Or is it a semi-abstract take on a non-human bipedal creature of some sort… something unknown to science!!

Caption: a redrawing of Breuil’s interpretation of the ‘Sorcerer’, from Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams’s 1998 book The Shamans of Prehistory. As discussed in the text, this may be too generous relative to the original. Image: Clottes & Lewis-Williams (1996).

At the time of writing I’ve recently watched the 2017 movie The Ritual, and - while watching it - I couldn’t help but wonder if the creature in that movie – I’ll say no more because spoilers, but it’s called the Jōtunn – was in some way inspired by the Trois Frères sorcerer. But it wasn’t.

Caption: a scene from The Ritual, a great movie I really liked. Image: Netflix/Collider (taken from here).

Anyway, we owe this view of the figure to Abbé Henri Breuil (1877-1961), priest, archaeologist and master of French cave art. Breuil did a lot of good work and came up with many influential ideas on why, when and how cave art was produced (most famously in Breuil (1952)), but he wasn’t ashamed to speculate way beyond the confines of the data and at least some of his thoughts on the art involve a lot of interpretation that’s difficult to be at all confident about. Indeed, photos of the image show that a substantial amount of imagination is required to turn the fuzzy, partly indistinct humanoid figure visible today into the antlered novelty that Breuil depicted, and it simply isn’t possible to be confident that his take on the image is valid. Some people say that this is because photos typically don’t capture the subtleties of the images (which are often formed of cracks and lumps on the rock and hence don’t transfer well to flash photography), and others that the image may have faded or degraded since Breuil drew his take on it during the 1920s.

Caption: a post-Breuil photograph of the image. As you can see, it doesn’t definitely show the many details he thought it did. But were they present originally and later lost, or not captured in photos? Image: strangehistory.net (from here).

Whatever’s going on, there’s clearly something unusual in the original art. We’re seeing an interesting image of some kind.

3. The Lion Statuette of Isturitz. Big cats are depicted in several European caves and are most usually images of cave lions (and a whole article could be written on what that cave art tells us about life appearance and behaviour in Pleistocene European lions). A few depictions, however, show other cat species (like leopards). The Isturitz cave in Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France, yields some of Europe’s most interesting Palaeolithic art, and among this is a 16 cm long statuette of a big cat, seemingly shown with a short tail, rectangular face, prominent chin, and sparse array of spots across its upper surface. Conventionally identified as a lion, it was argued by Vratislav Mazak (1970) to instead be a depiction of the sabretooth Homotherium. This would be pretty radical for several reasons: not only would it be the only known human-made image of a sabretooth on record (though read on), it would also require that Homotherium persisted in Europe much later than anyone had previously thought (to 30,000 years ago, rather than to 300,000 years ago). The statuette is lost today (sigh), but there is at least one photo of it.

Caption: a drawing of the Isturitz statuette, borrowed from Michel Raynal’s now defunct webpage (a newer drawing of the image has since been produced by Mauricio Antón; see Antón et al. 2009). Lion or scimitar-toothed cat?

Mazak’s idea was accepted by several other authors, most notably Michel Rousseau (1971a, b), who argued that several other European Palaeolithic illustrations could depict Homotherium as well. The idea was made better known thanks to the coverage it received from Shuker (1989) and Guthrie (2005). And in 2000 it received what looked like support from the discovery of a geologically young Homotherium fossil (a lower jaw from the North Sea), dated to c 28,000 years ago (Reumer et al. 2003). So far, so good – maybe the Isturitz statuette gives us an unparalleled insight into the life appearance of an iconic sabretooth.

But… no. In a detailed re-examination of the case, Mauricio Antón and colleagues argued that it isn’t a depiction of Homotherium at all, but a Cave lion Panthera leo spelaea (Antón et al. 2009). They argued (following rigorous and detailed anatomical assessment of the life appearance of Homotherium) that the statuette lacks the longish neck, level (rather than convex) dorsal outline to the head, protruding canine tips, and sloping back that would be evident if this really was a depiction of Homotherium. I find these arguments pretty compelling and think that the statuette is a lion after all. Probably.

Caption: Antón et al. (2009) argued that Homotherium (A, B) would differ noticeably from Cave lion (C, D) in proportions. The homothere has taller shoulders, a longer neck, a flatter head, and a more sloping back than a pantherine like a lion. Image: Antón et al. 2009.

Long-time readers might recall this as something I covered way back at TetZoo ver 1. That article (with about half of all the other TetZoo ver 1 articles) is included in my 2010 book Tetrapod Zoology Book One (Naish 2010). Book Two will be published this year or in 2020, incidentally.

4. The Beast-Women of Isturitz. Isturitz is also the discovery site of an engraved piece of bone that features a bison on one side, and two humanoids on the other. The humanoids are depicted in side view, as if swimming past the viewer, and they appear to be women. But they’re very unusual women.

Caption: one of several photos showing the famous Isturitz ‘bison and two women’ engraved bone shard. This is a replica on display at Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye. Image: Don Hitchcock, from donsmaps.com.

For one thing, while they’re certainly human-like, they aren’t as human-like as regular humans. The one breast we see is shown hanging from the armpit region, rather than at the front of the chest, the profile of the face is not especially human-like and features an unusual protruding nose, and the body is unusually massive and stocky, exceeding the proportions of a human with substantial body fat. Additionally, the figures have collars or binding around their necks and wrists, and one of them has a barbed harpoon symbol on its thigh – the exact same symbol elsewhere shown on prey animals, like the bison on the other side of the engraving.

Caption: drawings of the same piece, this time showing both the bison side and the ‘two women’ side. Image: this version appeared in Heuvelmans & Porchnev, but is taken here from donsmaps.com.

The most likely explanation is that these are stylized or badly drawn figures, and that we’d be silly to over-interpret them and think that they’re meant to be anatomically accurate in all their details. Perhaps the harpoon symbols show the images represent one or more particularly unpopular members of the tribe (maybe this is even a deliberate parody or cartoon), or perhaps this is a sort of Palaeolithic ‘most wanted’ poster (Bahn & Vertut 1997) and maybe the collars and wrist bindings are just ornaments or jewellery.

I can’t resist mentioning, however, the far more out-there idea that these aren’t depictions of Homo sapiens, but of another hominin species, and one that differs from ours in being more massive, different in head and nose shape, and in being regarded by us as an enemy or prey species, or even a beast of burden. The idea has been seriously proposed in the cryptozoology literature wherein it’s argued that ancient humans knew, and sometimes depicted in art, a more bestial, snub-nosed hominin that was perhaps part of H. neanderthalensis (Loofs-Wissowa 1994, Raynal 2001, Heuvelmans 2016). Regular readers will recall me covering this very niche take on prehistoric hominins in my 2016 review of Bernard Heuvelmans’s book Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman. I don’t think it’s a valid take on these illustrations, but… come on, it’s such a fun idea.

Caption: Heuvelmans and a few other authors argued that Neanderthals were bestial creatures with an enlarged upturned nose. I covered this whole take on Neanderthals in my review of Heuvelmans (2016), here. Image: Heuvelmans 2016.

5. Great auk… or Long-Necked Sea Monster? Finally, birds are not especially abundant in ancient rock art, but nevertheless such species as owls, swans, geese, duck and herons were all depicted on occasion. Among the most interesting of ancient birds in rock art are those at Cosquer Cave in Marseille, France, an amazing cave – discovered in 1985 and only announced in 1991 – with a submerged undersea entrance. The birds here are big-bodied, short-legged, and with flipper-like wings and a small head, and the most popular identification is that they’re Great auk Pinguinus impennis*. That would be a big deal since it would be the first rock art of that species; it would also be consistent with fossil evidence showing that this species occurred in the Mediterranean during prehistoric times.

* An error meant that these birds were initially announced as ‘penguins’. As many as you will know, the term penguin was originally applied to the Great auk, and only later applied to the sphenisciforms of the south.

Caption: the Cosquer Cave ‘penguins’. I don’t know who to credit this image to but will add info when I get it.

However, the Cosquer Cave illustrations don’t look much like Great auks at all – this suggestion could be completely wrong, or it could be that they’re schematic or abstract depictions of this species. Indeed, some experts think that providing a specific identification like this is going too far and that it might be better to just identify them as generic seabirds (Bahn & Vertut 1997).

Caption: is the Cosquer Cave animal really a depiction of a Great auk? Hmm, maybe… but the similarity isn’t actually convincing. Images: auk by Darren Naish; Cosquer Cave animal from Mysterious Universe (here).

An even more exotic suggestion is that the massive body, stumpy tail, flippers and small head of these animals makes them look like…. the long-necked sea monster – a sort of enormous seal with a long neck and a humped back – endorsed by some cryptozoologists (most famously Bernard Heuvelmans, who proposed the name Megalotaria longicollis for this creature).

Caption: one of the most familiar depictions of Megalotaria is this painting from Janet and Colin Bord’s article on sea monsters from the partwork series The Unexplained (and latterly included in the book Creatures From Elsewhere). Not sure who the artist was. Image: (c) Orbis Publishing.

Yes, the idea that these might be depictions of a sea monster are out there in the cryptozoology literature, specifically in a 1994 article by François de Sarre*. Given that this idea requires Megalotaria to be real (something I don’t endorse, regretfully: see Woodley et al. 2008), I don’t think that this is an especially good idea, though I do agree that there’s a superficial similarity.

In the end, the idea that these images can be precisely identified to a species is probably erroneous, as it is in many similar cases. People must surely have drawn things badly, or in abstract fashion, or perhaps with only partial or second-hand knowledge of the animal concerned. And sometimes they might have made things up, or mashed things together.

* I’ve misplaced my copy of this article and can’t provide the full citation. But an online version is here, and an article inspired by de Sarre’s is here.

And that’s a good point to end on. Prehistoric rock art – produced over tens of thousands of years, by all manner of different groups of people with all kinds of influences, motivations, beliefs, experiences, artistic techniques, materials and technologies – no more performs the same function as human-made images do in the modern world. Some depictions were meant to be true to life, and to be educational, practical or naturalistic; others were abstract, symbolic, whimsical or even satirical; and surely others were practise pieces, or the work of individuals less skilled than others. We must not, I think, assume that everything can be identified to a known animal species with certainty or confidence.

For previous TetZoo articles on ancient rock art and related issues, see…

The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats, March 2006

Tet Zoo picture of the day # 3 (Elasmotherium), May 2007

The remarkable life appearance of the Woolly rhino, November 2013

Spots, Stripes and Spreading Hooves in the Horses of the Ice Age, February 2015

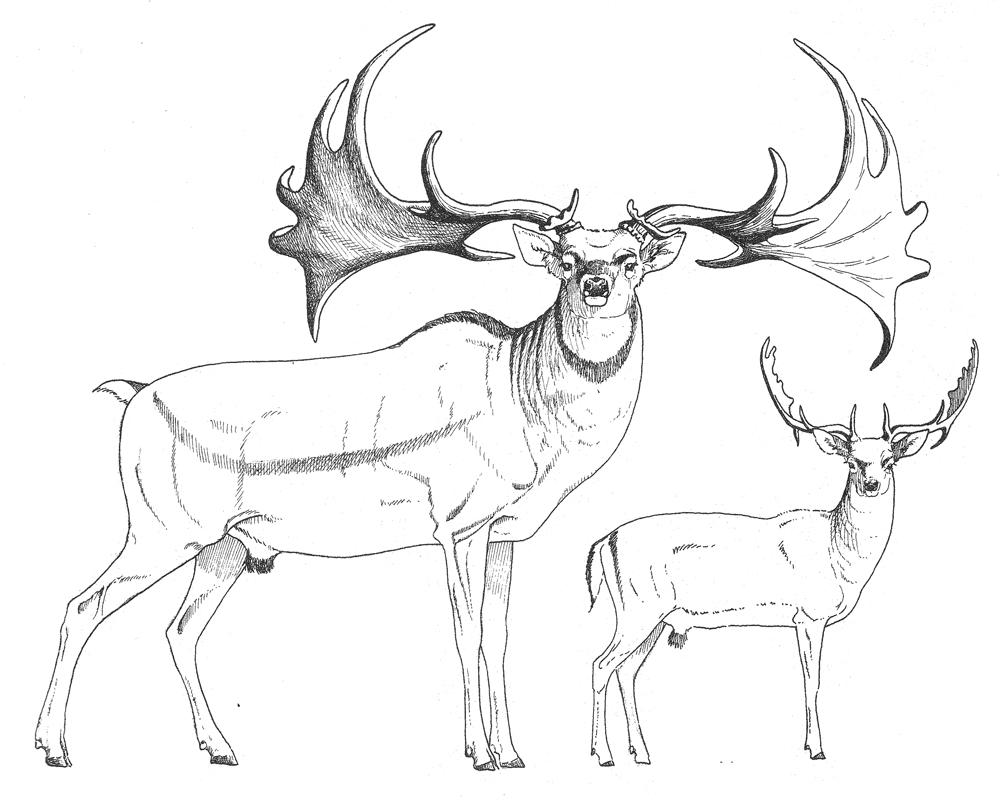

The Life Appearance of the Giant Deer Megaloceros, September 2018

Refs - -

Antón, M, Salesa, M. J., Turner, A., Galobart, Á. & Pastor, J. F. 2009. Soft tissue reconstruction of Homotherium latidens (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae). Implications for the possibility of representations in Palaeolithic art. Geobios 42, 541-551.

Bahn, P. G. & Vertut, J. 1997. Journey Through the Ice Age. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

Breuil, H. 1952. Four Hundred Centuries of Cave Art. Hacker Art Books.

Kurtén, B. 1968. Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

Loofs-Wissowa, H. 1994. The penis rectus as a marker in human palaeontology? Human Evolution 9, 343-356.

Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Miller, A. Z. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. 2015. Lascaux Cave: an example of fragile ecological balance in subterranean environments. In Engel, A. S. (ed) Microbial Life of Cave Systems, De Gruyter, pp. 279–302.

Mazak, V. 1970. On a supposed prehistoric representation of the Pleistocene scimitar cat, Homotherium Farbrini, 1890 (Mammalia; Machairodontinae). Zeitschrift fur Saugertierkunde 35, 359-362.

Naish, D. 2010. Tetrapod Zoology Book One. CFZ Press, Bideford.

Raynal, M. 2001. Jordi Magraner’s field research on the bar-manu: evidence for the authenticity of Heuvelmans’ Homo pongoides. In Heinselman, C. (ed) Hominology Special Number 1. Craig Heinselman (Francestown, New Hampshire), unpaginated.

Reumer, J. W. F., Rook, L., Van Der Borg, K., Post, K., Mol, D. & De Vos, J. 2003. Late Pleistocene survival of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium in northwestern Europe. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23, 260-262.

Rousseau, M. 1971a. Un félin à canine-poignard dans l’art paléolithique? Archéologia 40, 81-82.

Rousseau, M. 1971b. Un machairodonte dans l’art aurignacien? Mammalia 35, 648-657.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1989. Mystery Cats of the World. Robert Hale, London.

Remembering Lyall Watson’s Whales of the World

I’ve written before about some of the books that had an undue influence on me during my formative years. Such books tend to be well illustrated, they mostly contain attractive, colourful, detailed pieces of art, and they usually showcase weird and surprising proposals and arguments that later proved erroneous, questionable or wrong. The fact that I’ve always considered such books especially interesting and/or influential surely says a lot about me and how my brain works, but whatever.

Caption: the somewhat worn cover of my copy of Watson’s Whales of the World (the 1988 softback edition). Image: Darren Naish.

Today I’d like to discuss another of these fondly remembered books, and if you know it as well as I do you may well understand where I’m coming from. If you don’t know the book at all, (1) what have you been doing with your life?, and (2) obtain the book for yourself, it’s worth it. I’m here to discuss the weird, wonderful Whales of the World (also published as Sea Guide to Whales of the World) by the late Lyall Watson, illustrated by Tom Ritchie, and subtitled ‘A Complete Guide to the World’s Living Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises’ (Watson 1981).

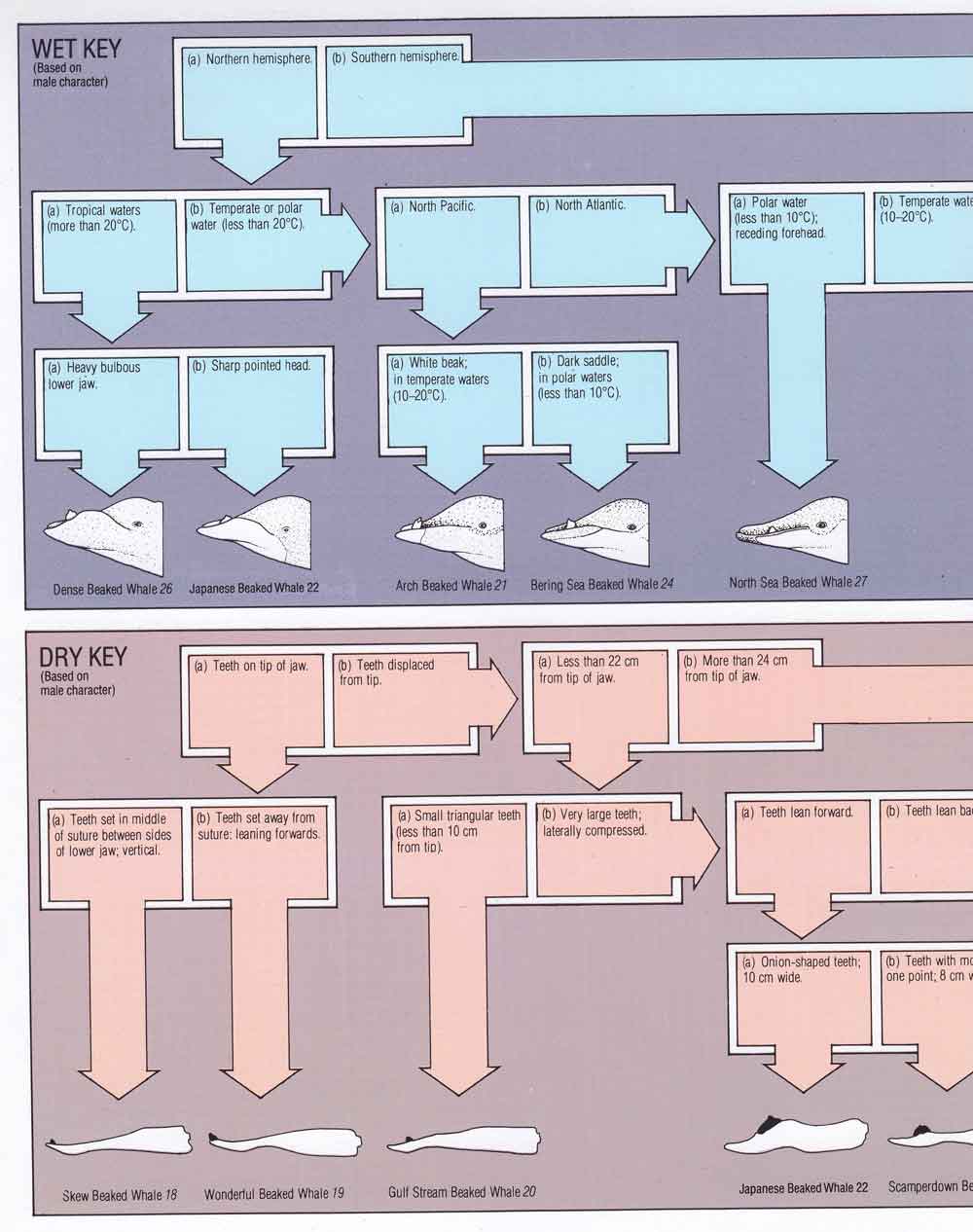

Watson (1981) is a robust, attractively designed volume of 302 pages that goes through all the cetacean species thought valid by the author at the time of writing. It saw at least three reprintings, the first edition being hardback with a dustjacket, the 1985 and 1988 editions being softbacks. The book is arranged taxonomically and groups the cetaceans together by family, each family section including an introduction that has a key and a guide to the family’s respective anatomical traits. The family-level taxonomy Watson used is a little idiosyncratic, on which more later. Each species gets its own two pages. These include a distribution map, colour illustration (sometimes showing variants and juveniles where appropriate), an image of the skull where possible, and text sections on Classification (read: taxonomic history and discovery), Local Names, Description, Stranding, Natural History, Status, Distribution, and Sources (there’s a good bibliography).

Caption: Watson (1981) includes both ‘wet keys’ (providing information on the life appearance of cetaceans, and intended to be used in the field) and ‘dry keys’ (providing information on skeletal material meant to be used to identify stranded animals or carcasses). Image: Watson 1981.

Who was Lyall Watson? Before we move on to the things that make the book unusual, we must ask: who was Lyall Watson? I recall being surprised on first learning of the existence of this book given that Watson was, and still is, best known for his 1973 Supernature: The Natural History of the Supernatural, a book on inexplicable phenomena and how they might be connected and explained. Supernature reads much like woo today, and it’s not surprising that Watson was regarded as embarrassingly credulous and even dishonest by some, and as refreshingly open-minded by others. I knew Watson for these reasons before discovering (by chance, in a bookshop… pre-internet days, kids) that he’d published a book on whales.

Caption: at left: Dr Lyall Watson. At right: 1973’s Supernature, Watson’s most famous book. Images: list of quotations of Lyall Watson (here), goodreads.com (here).

A look at the titles of his more than 20 published works reveals a remarkable and eclectic interest in all of natural history, in sport, culture and ritual (witness the 1989 Sumo: A Guide to Sumo Wrestling), in biology, anatomy and evolution, in the elements and physical geography, in the paranormal and spiritual, and in the human experience and everything about it. Many of us are interested in most or even all of these things, but scarcely any have the skill and knowledge that might allow us to write books on them. In keeping with his diverse interests and writing abilities, he was tremendously qualified, holding degrees in botany, zoology, ecology and anthropology. He even studied palaeontology under the great Raymond Dart. Watson completed his PhD on animal behaviour at the University of London under Desmond Morris, another scientist and author well known for a diverse skillset and ability to write engagingly about remarkable and controversial subjects. Unsurprisingly, Watson moved into the world of TV and also worked as a consultant for zoo and safari park design. Watson died in 2008 and there are some very good obituaries available online.

Anyway, back to the book. What makes it unusual?

Caption: several of Ritchie’s whales, composited together (it might be obvious that I especially like beaked whales). Clockwise from upper left, we’re seeing Fraser’s dolphin Lagenodelphis hosei, Peale’s dolphin Lagenorhynchus australis, Strap-toothed whale Mesoplodon layardii, Rough-toothed dolphin Steno bredanensis and Blainville’s beaked whale M. densirostris; Baird’s beaked whale Berardius bairdii is the big animal in the background. Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Whales of many hues. A key aspect of this book concerns its fantastic artwork. The whales look accurately proportioned and each illustration is nicely detailed. They’re not by Watson, but by artist Tom Ritchie. Watson states in a foreword how he and Ritchie travelled far – both north and south, he says – aboard the MS Lindblad Explorer in search of cetaceans. When describing the field sign, appearance and behaviour of cetaceans, he often describes things from the point of personal experience. Watson also states that he and Ritchie looked at numerous specimens in museum collections and also that they had access to new data never before published: the image of the Vaquita Phocoena sinus – named Gulf porpoise in the book (more on taxonomy in a minute) – “is taken from life and is the first ever printed which shows what the animal looks like” (Watson 1981, p. 8).

Caption: Ritchie’s Vaquita - at top - is apparently the first published full-body depiction of this animal’s life appearance. Below, a photo of a Vaquita in life. Extinction looms for this small cetacean. Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981, Paula Olson/NOAA, in public domain (original here).

In view of all this, I find it fascinating that Ritchie’s cetaceans are often more boldly and brightly marked than those illustrated in other works, and depicted in hues that look surprising in view of more typical reconstructions (yes, it might be justifiable to term some depictions of living cetaceans reconstructions, since they’ve been cobbled together from diverse lines of evidence). The classic example is Stejneger’s beaked whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri (termed the Bering Sea beaked whale in the book). Photos and comments on this whale in living state show that it’s greyish brown, pale ventrally, and with off-white around the mouth and eyes. Ritchie’s version is warm brown dorsally, blue on its sides, white ventrally, and with a dark mask across the forehead and eyes (Watson 1981, p. 139). It’s an enhanced, technicolor version of the whale, and so different from other takes on this species that you’re left wondering how accurate it is. This sort of thing occurs throughout the book. The illustrations and wonderful and really attractive, but it’s difficult to be sure that they’re trustworthy.

Caption: Ritchie’s depiction of Stejneger’s beaked whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri. The hues and pattern depicted here are very different from other takes on the appearance of this animal. Image: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Caption: I once wrote an April Fool’s article whereby a newly designed machine was said to have revealed the true life appearance of whales (it’s here at TetZoo ver 3). The imaginary multi-coloured whales devised for that spoof article were in part inspired by Tom Ritchie’s illustrations. Images: Gareth Monger and Darren Naish.

A heterodox phylogeny and taxonomy. A great strength of Watson (1981) is that it includes a fairly decent exposition on cetacean evolutionary history (now very dated of course) and copious discussion throughout of how anatomical characters group species together. What makes the book look odd today, however, is that Watson’s ideas are often heterodox and discordant with consensus views on these issues. We might expect no less of Watson given his other writings, but we might also wonder if the urge to shake things up a bit and promote new or minority opinions was a product of the time in which Watson was working (the late 1970s).

An early section in the book explains how the two great cetacean groups – mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (or toothed whales) – can’t definitely be said to share a recent common ancestor and might have emerged independently, and it’s even implied that this might also be true of ‘archaeocetes’, the archaic cetaceans otherwise regarded as the ancestors of mysticetes and odontocetes. Cetacean polyphyly is a weird idea in view of how many details mysticetes and odontocetes share to the exclusion of other mammals, but it would have seemed new and exciting during the 1970s given that it had come to the fore in papers of the mid and late 60s (Yablokov 1964, Van Valen 1968). Watson (1981) opted to support it. It isn’t taken seriously today, the anatomical, fossil and molecular evidence supporting cetacean monophyly being overwhelmingly good.

It gets better. Watson (1981) also opted to follow some (otherwise mostly ignored or forgotten) taxonomic proposals for delphinoids, and recognised a distinct Stenidae for ‘coastal dolphins’ (Steno, Sousa and Sotalia) and Globicephalidae for pilot and killer whales and their close kin. Those familiar with the technical literature on delphinoid evolution will know that both names originated elsewhere and have complex histories (which I must avoid discussing here), but their use in a field guide was unusual and heterodox given the tradition of including all of these animals within Delphinidae.

Caption: Watson (1981) wasn’t the only popular volume of the late 20th century to adopt some aspects of ‘non-traditional’ taxonomy. Anthony Martin et al.’s 1990 Whales and Dolphins also includes a globicephalid section (Martin 1990), which opens with this fantastic artwork (by Bruce Pearson). Image: Bruce Pearson/Martin 1990.

I should add that, in other respects, Watson (1981) seems conservative. Caperea is included within Balaenidae, the Kogia whales are included within Physeteridae (rather than their own Kogiidae; in this instance Watson states a preference to stick with consensus) and all river dolphins are lumped into Platanistidae, as was tradition at the time (though he noted that “There ought to perhaps be at least 3 separate families”, p. 148).

Caption: Watson’s Whales of the World includes various montage illustrations like this, which depict the field signs and characteristic markings of groups of species. The pictures look great. However, it has been argued that some of the details shown here are not wholly reliable (read on). Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Smash the patronymy. On the subject of taxonomy – this time on common names rather than scientific ones – another bold move is the assertion that an overhaul is needed in naming conventions, and that biologists and naturalists should absolutely move away from the time-honoured tactic of naming animals after people. After all, calling a given animal – say – ‘Smith’s mouse’ tells you nothing at all about the mouse, does nothing to honour the remarkable features of said mouse, and is positively unhelpful should you see said mouse in the field and wish to remember its name. No, it should be the Epic blue mouse, or the Great spectacled forest mouse, Watson opined. I agree with this idea and also think that names should honour organisms. With this approach in mind, you won’t, then, find True’s beaked whale, Commerson’s dolphin or Bryde’s whale in Watson’s Whales of the World, but the Wonderful beaked whale, Piebald dolphin and Tropical whale, respectively (Watson 1981). Many new names of this sort are proposed in the book.

Caption: close-up of Ritchie’s illustration of Shepherd’s beaked whale Tasmacetus shepherdi, one of my favourite living cetaceans. But it isn’t called Shepherd’s beaked whale in Watson (1981). Instead, it’s the Tasman whale. Image: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

However… language works best when we understand what other people are saying. When a word or name or turn of phrase is established and used throughout a community, it makes sense to stick with it, even if it’s misleading, technically inaccurate, or downright ‘wrong’. We can change it, but – I’d argue – we need to do so democratically, with input from as many relevant players as possible. I suppose a counter-argument is that someone has to get the ball rolling, and that proposing a new set of names in a book designed to function as a fieldguide is a good place to start.

Whatever the argument. Watson’s proposals didn’t win any accolade and his new names never became adopted by the cetological community. Maybe this was because he was an ‘outsider’ and lacked an established reputation as a whale expert or field biologist, but my main feeling is that most workers have wanted to stick with convention and continue to use the names that are otherwise entrenched.

Caption: my own whale illustrations - these were produced for various articles published back in the 1990s - were heavily inspired by those of Tom Ritchie. The originals of these illustrations appear to be lost today, so I have to draw them all anew for my in-prep textbook. Image: Darren Naish.

The reception to Whales of the World. Having just noticed that Watson was seen as “an outsider”, it’s worth finishing this article by wondering how Whales of the World was received and perceived by specialists. Among whale researchers in general, the book was mostly ignored and generally regarded as problematic. Typical comments were provided by marine mammal specialist Niger Bonner (who wrote several excellent volumes on pinnipeds and cetaceans himself). Bonner noted that the book had noble aims but was marred by errors and erroneously gave the impression that many of the species were far better known than they really were (Bonner 1983). He criticised the maps, thought that the new naming system was arbitrary, confusing and annoying, and noted that the colours given to the animals in the artwork didn’t always match what was stated in the text (Bonner 1983).

So far as I can tell, these comments were and are typical, and what was – and remains – a popular and much-read book by amateurs and enthusiasts was never endorsed or recommended by those who know whales best.

Caption: of all the popular and semi-technical books on cetaceans and other marine mammals, Watson (1981) remains one of the most interesting and attractive. This photo is from 2015 and I’ve acquired quite a few additional relevant volumes since. Image: Darren Naish.

I’m not a whale specialist, but I love the book, the caveat being – as should be obvious by now – that I love it for its weirdness and its design and artwork, not because I’ve ever found it an indispensable go-to work or a definitive take on the whales of the world. I’d say you should definitely get hold of it if you want a somewhat quirky, exciting take on the subject, or if you’re a completist or want to see Watson’s take on phylogeny, taxonomy and cetacean life appearance.

Cetaceans have been covered at length on TetZoo before - mostly at ver 2 and ver 3 - but these articles are now all but useless since all their images have been removed (and/or they’re paywalled, thanks SciAm). Here are just a few of them…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Scaphokogia!, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015 (but now lacking all images)

Refs - -

Bonner, N. 1983. [Review of] Sea Guide to Whales of the World. Oryx 17, 49.

Martin, A. R. 1990. Whales and Dolphins. Salamander Books Ltd, London and New York.

Van Valen, L. 1968. Monophyly or diphyly in the origin of whales. Evolution 22, 37-41.

Watson, L. 1981. Whales of the World. Hutchinson, London.

Yablokov, A. V. 1964. Convergence or parallelism in the evolution of cetaceans. Paleontological Journal 1964, 97-106.

The New World Leaf-Nosed Bat Radiation

I’ve said a few times here at TetZoo that bats have never really been given adequate coverage. This isn’t because I’m not interested in them: on the contrary, I think about bats more than I think about most other groups of mammals, and I see them and watch them more often than I do most other mammal groups. For a group that includes about 18% of extant mammalian species (using 2019 figures*), I can’t pretend to have ever given bats fair coverage. Having said all that, bats have actually been covered at TetZoo a fair bit: there was an entire 20-part series on vesper bats (properly Vespertilionidae) at ver 3, and I also published several ver 2 articles on the history and evolution of vampire bats, and on much else besides. The fact that all of these articles have been rendered worthless via the removal of their images is mightily dispiriting though, and essentially means that I need to start from scratch.

* c 6495 mammal species, c 1200 bat species.

Caption: TetZoo Towers bat library. The several boxfiles of reprints and photocopied articles are not shown. Image: Darren Naish.

Here, I want to talk about a group I don’t think I’ve ever covered at TetZoo before, namely the phyllostomids, or New World leaf-nosed bats, American leaf-nosed bats or spear-nosed bats. This is a large, American group that contains around 200 living species, making it the third largest bat family (vesper bats are the biggest group, followed by fruit bats). The group has sometimes been called Phyllostomatidae – the vernacular version of which is phyllostomatid – but this is less popular than Phyllostomidae. I have no idea which is really correct here and opt to merely follow majority usage on these sorts of things (insert quote from Gene Gaffney**). It’s not strictly true that I’ve never covered phyllostomids before, since vampires – once upon a time given their own eponymous family (Desmodontidae) – are now universally agreed to be nested within Phyllostomidae, and I have at least written about them.

Caption: Chrotopterus, a big spear-nosed bat. Notice how this bat has relatively broad, low-aspect wings and a large, deep uropatagium (the membrane between the legs). Contrast this with some of the images below. Image: George Henry Ford, public domain (original here).

Phyllostomids occur from Argentina in the south to the southern USA (Nevada being their most northerly occurrence) in the north, and they’re highly diverse ecologically and behaviourally. They include insectivores, frugivores, nectarivores, palynivores (that’s pollen-eaters), omnivores, animalivores and (of course) obligate sanguivores. Numerous different taxonomic subdivisions have been named. We don’t need to worry about any of this in detail but, in simplified terms, Macrotinae (big-eared bats), Micronycterinae (little big-eared bats) and Desmodontinae (vampires) are outside a much larger clade that includes Vampyrinae (false vampires and kin) and Phyllostominae (spear-nosed bats and kin) as well as the nectarivorous and frugivorous Glossophaginae (long-tongued and long-nosed bats) and Stenodermatinae (American fruit bats, fig-eating bats and kin) (Baker et al. 1989, 2003, 2012; but see Wetterer et al. 2000). Vampyrinae is a clade within Phyllostominae according to some studies, in which case it gets down-graded to Vampyrini (Baker et al. 2003). All of this is depicted in a cladogram below.

Phyllostomids are mostly brownish bats with simple, narrow ears. A nose-leaf – typically simple and spear-shaped – is common but not present in all species, a tragus is always present, and many (but not all) of the species that lack nose-leaves have chin-leaves (or a series of chin ‘warts’) instead. Facial stripes are common, dark dorsal stripes are present in a few species, and such things as white patches at the wing tips and yellow rims to the ears and nose-leaves are present in some (Hill & Smith 1984). The tail is variously long, or short, and even absent altogether in some taxa, and similar variation is present in the uropatagium, or tail membrane.