One of the most fascinating episodes in the history of palaeontology is that of Piltdown man, an alleged human ancestor discovered in 1908 at Piltdown in Sussex, England…

The Cautious Climber Hypothesis

Those of you familiar with the literature on hominid evolution will doubtless have read at least something about the evolution of hominid bipedality. In the most popular model, bipedal hominids originated from terrestrial, chimp-like quadrupeds (which were still capable of climbing but not highly specialised for it), sometime within the last 7 or so million years. However, committed adaptation to full-time bipedality did not occur until more recently, and at least some of the hominids included within the ‘australopithecine’ grade of our lineage (and it obviously is a grade, even Australopithecus itself – as currently conceived – being paraphyletic) were seemingly not far from chimps and bonobos in climbing ability.

Caption: hominids - represented here by a gorilla, orangutan and chimpanzee (the human needed to complete the scene is missing) - are different from other anthropoid primates in many important aspects. What particular adaptational history caused them … us… to be so different? This mural is on show at Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland, and is by Russell Dempster. Image: Darren Naish.

This shift likely occurred in open habitats, and quite why bipedal adaptation evolved has been the subject of copious speculation. Maybe it was to do with being able to see further, to free up the hands for carrying things, to improve social and/or sexual communication, to assist with thermoregulation, to increase foraging reach, to improve wading abilities or… insert favoured model for origin of bipedality here.

Caption: primate evolution is another of those subjects that gets written about a lot. Here are some of the (mostly hominid-themed) primate books in the TetZoo collection, but far from all of them. Pet and fringe theories abound in the popular and semi-popular literature on hominid evolution. Image: Darren Naish.

What I’ve just described might be regarded as ‘the textbook view’, however, since there are indications that things might not have happened as described. Anatomical details suggest that proficient bipedal abilities might not have originated in open, terrestrial environments, but in wooded habitats, earlier in history, and among taxa that spent more time in trees than on the ground.

There’s a lot more that could be said about that particular area, but here I want to concentrate on an even earlier phase of evolution. Namely, that part relevant to those hominoids in existence prior to the split between pongines (orangutans and their relatives) and hominines (African great apes). Such animals can be termed stem-hominids, pre-hominids or early hominoids, depending on your preference, and they’d be closer in position to hominids than are gibbons (aka hylobatids). I’m going to call them ‘pre-hominids’ since I find this to be the least ambiguous term. Which behavioural, locomotory and ecological specialisations led to the evolution of the hominid body form, and what were pre-hominids like?

Caption: the red box shows the section of the family tree we’re especially interested in here. The animals concerned are hominoids, but not part of the hominid crown (that is, they’re not part of the hominid group delimited by living hominid lineages). They’re stem-hominids, or ‘pre-hominids’. Image: Darren Naish.

Some authors have proposed that pre-hominids were gibbon-like brachiators (perhaps pre-adapted for bipedality). This is the so-called brachiation, brachionationist or hylobatian model (e.g., Morton 1926, Keith 1934, Tuttle 1981). Others have argued that pre-hominids were more terrestrial, chimp-like knuckle-walkers (e.g., Keith 1923, Washburn 1963), a model similar to the ‘trogolodytian’ one actually proposed as a phase within the hylobatian model. Neither of these models, however, appears consistent with the long list of features that hominids share with mammals that are neither brachiators nor terrestrial quadrupeds, but vertical climbers that use what’s termed an antipronograde posture (where the body’s long axis is oriented more than 45° from the horizontal). The proportionally long arms and short legs of hominids (we’re referring here to the assumed ancestral condition, not that possessed by unusual forms like humans), the short thorax, reduced lumbar region where vertebrae are incorporated into the sacrum, wide shoulders and hips, and the anatomy of the shoulders, wrists and feet all parallel features seen in lorises and kin, and in climbing South American monkeys like spider monkeys (Sarmiento 1995). In short, these features – and there’s other evidence too, relating to the way muscles function and so on – suggest that pre-hominids were perhaps specialised for vertical climbing.

Caption: which form of locomotion was typical of those hominoids ancestral to hominids? Were they brachiators, arboreal climbers, or digitigrade or knuckle-walking terrestrial forms? Image: Richmond et al. (2001).

We can go further, since hominids don’t merely possess general features associated with vertical climbing: they have additional features specific to what are known as cautious climbers. These are those vertical climbers that rely on the grasping of (sometimes discontinuously sized) supports and do not leap. Cautious climbers among mammals include lorises, some colobine monkeys, tree sloths and the extinct palaeopropithecid lemurs (Sarmiento 1995) (though some of these taxa – sloths in particular – have specialised for suspensory climbing too). The features we’re talking about here include dorsal migration of the scapula relative to its position on the ribcage in other primates, increased breadth of the manubrium (the big, anterior-most section of the sternum), a reduced number of tracheal rings, a flat-topped diaphragm with a central tendon, a tendon that connects the protective membrane around the heart to the diaphragm (termed the pericardiophrenic tendon), and reduction or loss of the tail.

Caption: did hominids start their history as ‘cautious climbers’, convergently similar to such arboreal mammals as lorises, sloths, various leaf-eating Old and New World monkeys, and some extinct lemurs? The pre-hominid at far right is a hypothetical animal - a ‘concestor’ - that matches this prediction. A slow loris and three-toed sloth are shown at left. Image: Darren Naish.

Because living cautious climbers share a set of physiological, anatomical and behavioural features, we can infer that they were likely present in cautious climbing pre-hominids too. Cautious climbers use slow, deliberate movements, often hold the foot in a hooked pose, use the foot from the toes to the heel when grasping, and are often bipedal when on the ground. Their slow, deliberate and often powerful movements are in keeping with a high proportion of slow twitch or red muscle fibres (Sarmiento 1995).

Cautious climbers also tend to be – but are not always – folivores (leaf eaters), and their reliance on leaves means that they’ve evolved large guts and have slow metabolisms. They’re therefore mostly big (c 10-40 kg), bulky animals with long gestation periods and a reliance on tropical habitats with a guaranteed supply of canopy foliage. Their slow metabolisms also predict that they’re relatively good at dealing with toxins, and it’s been argued that their slow-moving, low-energy strategy makes them inclined to evolve laryngeal specialisations and an ability to broadcast loud sounds over distance.

Caption: cautious climbers generally don’t leap, or drop from height onto other structures when climbing. Instead, they mostly climb slowly and deliberately, with actions like these (here depicted in a potto) being used to move from one branch to another. Image: Napier & Napier (1985) (and based on an original by Charles-Dominique).

The idea that pre-hominids were cautious climbers of this sort, and that the biological and ecological correlates of this adaptive regime were present in these animals, was explored in depth by Esteban Sarmiento in a few papers from the 1990s (Sarmiento 1995, 1998). The significance of the cautious climber model is not just that it better allows us to imagine what pre-hominids might have been like; it’s also interesting in that imagining hominids as animals that went through this phase helps explains why they were evolutionary shaped in the ways that they were.

Caption: hominid skeletons - this is that of an orangutan, photographed at Musée d'histoire Naturelle, Tournai (Belgium) - possess numerous features indicative of arboreal adaptation. Image: Michel Wal, CC BY-SA 3.0, wikipedia (original here).

Hominids took to frugivory on later occasions within their history, for example, but a folivorous initial phase might explain why they have the teeth that they do (the incisors are relatively small, the canines are shortened, there are crushing surfaces on the premolars, enamel wrinkling is present on the molars, and so on), why the front of the face is reduced, and why the lower jaw has such a large and vertical ascending process, a big section adjacent to the molars and a broad but short condyle (Sarmiento 1995). A folivorous heritage could also help explain why hominids are relatively slow growing, resistant to many poisons toxic to other mammals, and equipped with an ability to make loud, complex calls. It would appear, however, that pre-hominids were not as specialised for folivory as are cautious climbers like sloths, since hominids never evolved a complex stomach and always maintained good terrestrial abilities.

Was Sarmiento right about cautious climbing and folivory being all that important in primates close to the ancestry of later hominid lineages? This isn’t an area that’s been all that intensively discussed but – when comments on ‘pre-hominid’ evolution have been provided – authors have tended not to state special preference for the idea, at least considering it as likely as suspensory behaviour or generalised climbing (e.g., Pilbeam & Young 2004, Begun 2016). Richmond et al. (2001), however, noted that ideas positing antipronograde climbing postures were “[a]rguably the most popular [of evolutionary models pertaining to pre-hominid lifestyle] … during the last several decades” (p. 81) and argued that the anatomy and biomechanics of extant hominids are consistent with an arboreal climbing ancestry. They didn’t specifically have cautious climbing and/or folivory in mind though.

Caption: this article isn’t about SpecBio. But if pre-hominids were vaguely sloth-like in some ways, a different trajectory of hominid evolution might have resulted in a radiation of increasingly sloth-like primates… in which case, maybe things like this could have evolved. Maybe. This is Giganthropus, a fictional sloth-like hominid featured in Dougal Dixon’s 1990 Man After Man. Image: Philip Hood, in Dixon (1990).

As goes fossils, animals that pertain to the right approximate part of the cladogram do seem to provide support for the model. Morotopithecus from Early Miocene Uganda is large (20-40 kg) (Gebo et al. 1997) and has been inferred to have been a vertical climber (and perhaps a cautious climber), while Pierolapithecus from the middle Miocene of Spain has a set of features which appear inconsistent with suspensory behaviour and more in line with vertical climbing (Moyà-Solà et al. 2004) (and, again, perhaps with cautious climbing too).

All in all, I find the ‘cautious climber’ model of pre-hominid evolution intriguing and worthy of more attention, hence this article. Long-term readers might remember me mentioning this article – as an in-prep piece, waiting completion – for some years now. It is, at last, ticked off the list.

For previous TetZoo articles on primate diversity and evolution, see…

The Cultured Ape, and Attenborough on gorillas, April 2006

Zihlman’s ‘pygmy chimpanzee hypothesis’, October 2012 (but now missing all images)

Marmosets and tamarins: dwarfed monkeys of the South American tropics, November 2012 (but now missing all images)

The amazing swimming Proboscis monkey (part I), November 2012 (but now missing all images)

Nasalis among the odd-nosed colobines or The “Nasalis Paradox” (proboscis monkeys part II), December 2012 (but now missing all images)

Old World monkeys of choice, May 2014 (but now missing all images)

De Loys’ Ape and what to do with it, July 2014 (but now missing all images, thanks SciAm)

Why Humans Are Important to Studies of Primate Diversity, July 2014 (but now missing all images, thanks SciAm)

Books of the TetZooniverse: of Palaeoart, Bats, Primates and Crocodylians, August 2015

Piltdown Man and the Dualist Contention, October 2015

If Bigfoot Were Real, June 2016

Tet Zoo Bookshelf September 2016: of Fossil Primates and Nightjars, September 2016

Bigfoot’s Genitals: What Do We Know?, August 2018

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1990. Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future. Blandford, London.

Gebo, D. L., MacLatchy, L., Kityo, R., Deino, A., Kingston, J. & Pilbeam, D. 1997. A hominoid genus from the Early Miocene of Uganda. Science 276, 401-404.

Keith, A. 1923. Man’s posture: its evolution and disorders. British Medical Journal 1, 451-454, 499-502, 545-548, 587-590, 624-626, 669-672.

Keith, A. 1934. The Construction of Man’s Family Tree. Watts, London.

Morton, D. J. 1926. Evolution of man’s erect posture: preliminary report. Journal of Morphology and Physiology 43, 147-149.

Moyà-Solà, S., Köhler, M., Alba, D. M., Casanovas-Vilar, I. & Galindo, J. 2004. Pierolapithecus catalaunicus, a new Middle Miocene great ape from Spain. Science 306, 1339-1344.

Pilbeam, D. & Young, N. 2004. Hominoid evolution: synthesizing disparate data. C. R. Palevol 3, 305-321.

Richmond, B. G., Begun, D. R. & Strait, D. S. 2001. Origin of human bipedalism: the knuckle-walking hypothesis revisited. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 44, 70-105.

Sarmiento, E. E. 1995. Cautious climbers and folivory: a model of hominoid differentiation. Human Evolution 10, 289-321.

Sarmiento, E. E. 1998. Generalized quadrupeds, committed bipeds, and the shift to open habitats: an evolutionary model of hominid divergence. American Museum Novitates 3250, 1-78.

Tuttle, R. H. 1981. Evolution of hominid bipedalism and prehensile capabilities. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 292, 89-94.

Washburn, S. L. 1963. Behavior and human evolution. In Washburn, S. L. (ed) Classification and Human Evolution. Aldine, Chicago, pp. 190-201.

The Most Amazing TetZoo-Themed Discoveries of 2018

As we hurtle toward the end of the year – always a scary thing because you realise how much you didn’t get done in the year that’s passed – it’s time to look back at just a little of what happened in 2018...

Caption: animals we will meet below, a montage. Images: (c) Philippe Verbelen, (c) Kristen Grace, Florida Museum of Natural History, Graham et al. (2018), CC BY-SA 4.0.

This article is not anything like a TetZoo review of 2018 (I’ll aim to produce something along those lines in early 2019), but, rather, a quick look at some of the year’s neatest and most exciting zoological (well, tetrapodological) discoveries. As per usual, I intended to write a whole lot more – there are so many things worthy of coverage – and what we have here is very much an abridged version of what I planned.

Thanks as always to those supporting me at patreon. Time is the great constraint (and finance, of course), and the more support I have, the more time I can spend on producing blog content. Anyway, to business…

The Rote leaf warbler. New passerine bird species are still discovered on a fairly regular basis; in fact three were named in 2018*. One of these is especially remarkable. It’s a leaf warbler, or phylloscopid, endemic to Rote in the Lesser Sundas, and like most members of the group is a canopy-dwelling, insectivorous, greenish bird that gleans for prey among foliage. Leaf warblers are generally samey in profile and bill shape, so the big deal about the new Rote species – the Rote leaf warbler Phylloscopus rotiensis – is that its bill is proportionally long and curved, giving it a unique look within the group. It superficially recalls a tailorbird. Indeed, I think it’s likely that the species would be considered ‘distinct enough’ for its own genus if there weren’t compelling molecular data that nests it deeply within Phylloscopus (Ng et al. 2018).

* The others are the Cordillera Azul antbird Myrmoderus eowilsoni and the Western square-tailed drongo Dicrurus occidentalis.

Caption: a Common chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita encountered in western Europe, a familiar Eurasian-African phylloscopid leaf warbler. Image: Darren Naish.

The story of the Rote leaf warbler’s discovery is interesting in that it’s yet another recently discovered species whose existence and novelty was suspected for a while. Colin Trainor reported leaf warblers on Rote in 2004 but never got a good look at them, Philippe Verbelen observed them in 2009 and realised how anatomically unusual they were, and it wasn’t until 2015 that a holotype specimen was procured (Ng et al. 2018). I’ve mentioned before the fact that documenting and eventually publishing a new species is rarely an instant see it catch it publish it event, but a drawn-out one that can take decades, and here we are again. Also worth noting is that the existence of a leaf warbler on Rote was not predicted based on our prior knowledge of leaf warbler distribution in view of the deep marine channel separating Rote from Timor and lack of any prior terrestrial connection. Yeah, birds can fly, but members of many groups prefer not to cross deep water channels. In this case, this did, however, happen and most likely at some point late in the Pliocene (Ng et al. 2018).

Caption: Rote leaf warbler in life, a novel member of an otherwise conservative group. Image: (c) Philippe Verbelen.

Rote has yielded other new passerines in recent years – the Rote myzomela Myzomela irianawidodoae (a honeyeater) was named in 2017 – and it’s possible that one or two others might still await discovery there.

Neanderthal cave art. Hominins don’t get covered much at TetZoo, which is weird given the amazing pace of relevant recent discoveries and the fact that they’re totally part of the remit. I mostly don’t cover them because I feel they’re sufficiently written about elsewhere in the science blogging universe, plus I tend to be preoccupied with other things. Nevertheless, I take notice, and of the many very interesting things published in 2018 was Hoffman et al.’s (2018) announcement of several different pieces of Spanish rock art, seemingly made by Neanderthals Homo neanderthalensis. The art concerned involves hand stencils, abstract lines, squares and amorphous patches of pigment, always marked in red.

Caption: red abstract markings, discovered in several Spanish caves, are old, and in fact were seemingly made by hominins long before H. sapiens moved into Europe. The red sinuous marking and system of squares and lines near the middle of this photo are purported to have been made by Neanderthals (other images, depicting animals and present adjacent to these markings, were seemingly created more recently by H. sapiens individuals). Image: (c) P. Saura.

The main reason for the attribution of this art to Neanderthals is its age: uranium-thorium dating shows that it’s older than 64ka, which therefore makes it more than 20ka older than the time at which H. sapiens arrived in Europe (Hoffman et al. 2018). That seems compelling, and it’s consistent with a building quantity of evidence for Neanderthal cultural complexity which involves the use of shells, pigments, broken stalagmites and so on.

Caption: one of the most famous pieces of claimed Neanderthal rock art: the Gorham's Cave ‘hashtag’ from Gibraltar. Image: (c) Stewart Finlayson.

I should add here, however, that I’m slightly sceptical of the use of age as a guide to species-level identification. Why? Well, we have evidence from elsewhere in the fossil record that the range of a hominin species can be extended by around 100ka without serious issue (witness the 2017 announcement of H. sapiens remains from north Africa; a discovery which substantially increased the longevity of our species). In view of this, would a 20ka extension of H. sapiens’ presence in Europe be absolutely out of the question? Such a possibility is not supported by evidence yet, and I don’t mean to appear at all biased against Neanderthals.

A tiny Cretaceous anguimorph in amber, and other Mesozoic amber animals. As you’ll know if you follow fossil-themed news, recent years have seen the discovery of an impressive number of vertebrate fossils in Cretaceous amber, virtually all of which are from Myanmar and date to around 99 million years old. They include tiny enantiornithine birds, various feathers (most recently racquet-like ‘rachis dominated feathers’), the tiny snake Xiaophis, early members of the gecko and chameleon lineages and the small frog Electrorana. Many of these finds were published in 2018 and any one could count as an ‘amazing’ discovery.

Caption: the Barlochersaurus winhtini holotype, from Daza et al. (2018).

However, there’s one fossil in particular that I find ‘amazing’, and it hasn’t received all that much coverage. It’s the tiny (SVL* 19.1 mm!), slim-bodied anguimorph Barlochersaurus winhtini, named for a single, near-complete specimen subjected to CT-scanning (Daza et al. 2018). Remarkable images of its anatomical details are included in Daza et al.’s (2018) paper. It has short limbs, pentadactyl hands and feet and a slim, shallow, bullet-shaped skull. Phylogenetic study finds it to be somewhere close to, or within, Platynota (the clade that includes gila monsters and kin, and monitors and kin), or perhaps a shinisaurian (Daza et al. 2018). It could be a specialised dwarf form, or somehow more reflective of the ancestral bauplan for these anguimorph groups. Either way, it’s exciting and interesting. What next from Burmese amber?

* snout to vent length

Caption: Barlochersaurus in life. It’s about the size of a paperclip. Image: (c) Kristen Grace, Florida Museum of Natural History (original here).

The Reticulated Siren. Sirens are very special, long-bodied aquatic salamanders with reduced limbs and bushy external gills. They’re very weird. They can reach 95 cm in length (and some fossil species were even larger), lack hindlimbs and a pelvis, have a horny beak and pavements of crushing teeth, and eat plants in addition to gastropods, bivalves and other animal prey. A longish article on siren biology and evolution can be found here at TetZoo ver 3.

Caption: a life reconstruction of the Cretaceous siren Habrosaurus, showing features typical of the group. This animal could reach 1.5 m in total length. Image: Darren Naish (prepared for my in-prep texbook The Vertebrate Fossil Record, on which go here).

Until recently, just four living siren species were recognised. But it turns out that indications of a fifth – endemic to southern Alabama and the Florida panhandle – have been around since 1970 at least. Furthermore, they pertain to a big species, similar in size to the Great siren Siren lacertina. Known locally as the ‘leopard eel’ (a less than ideal moniker, given that there’s a real eel that already goes by this name), this animal has been published by Sean Graham and colleagues in the open-access journal PLoS ONE (Graham et al. 2018) wherein it’s formally christened the Reticulated siren S. reticulata. It reaches 60 cm in total length, has dark spots across its dorsal surface and a proportionally smaller head and longer tail than other Siren species.

A museum specimen of the species has been known since 1970 when its finder noted that it did “not conform” to descriptions of known species, and live specimens were collected by David Steen and colleagues in 2009 and 2014. Again, note that discovery and recognition was a drawn-out process. The discovery has, quite rightly, received a substantial amount of media coverage, and many interesting articles about the find are already online. Many of you will already know of David Steen due to his social media presence and Alongside Wild charity (which I’m proud to say I support via pledges at patreon).

Caption: the Reticulated siren paratype specimen, as described by Graham et al. (2018). Image: Graham et al. (2018), CC BY-SA 4.0. Original here.

The idea that a new living amphibian species 60 cm long might be discovered anew in North America in 2018 is pretty radical. I’m reminded of the 2009 TetZoo ver 2 article ‘The USA is still yielding lots of new extant tetrapod species’ (which is less fun to look at than it should be, since images aren’t currently showing at ver 2). Furthermore, Graham et al. (2018) discovered during their molecular phylogenetic work that some other siren species are not monophyletic but likely species complexes, in which case taxonomic revision is required and more new species will probably be named down the line.

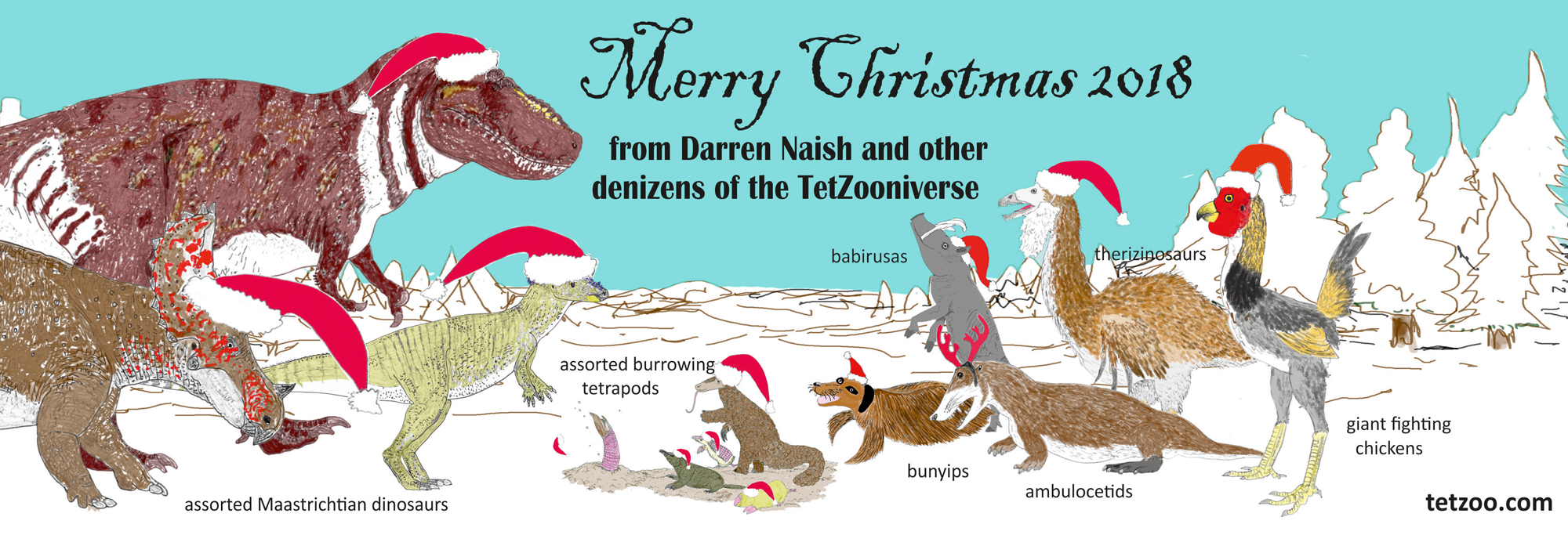

And that’s where I must end things, even though there are easily another ten discoveries I’d like to write about. This is very likely the last article I’ll have time to deal with before Christmas. As I write, I’m preparing to leave for the Popularising Palaeontology conference which happens in London this week (more info here), and then there are Christmas parties and a ton of consultancy jobs to get done before the New Year. On that note, I’ll sign off with a festive message, as is tradition. Best wishes for the season, and here’s to a fruitful and action-packed 2019. Special thanks once again to those helping me out at patreon.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to various of the subjects covered here, see…

The USA is still yielding lots of new extant tetrapod species, July 2009

THE AMAZING WORLD OF SALAMANDERS, October 2013

Chiffchaffs: a view of passerines from the peripheries (part I), August 2014

The Biology of Sirens, June 2016

Refs - -

Daza, J. D., Bauer, A. M., Stanley, E. L., Bolet, A., Dickson, B. & Losos, J. B. 2018. An enigmatic miniaturized and attenuate whole lizard from the mid-Cretaceous amber of Myanmar. Breviora 563, 1-18.

Hoffman, D. L., Standish, C. D., García-Diez, M., Pettitt, P. B., Milton, J. A., Zilhão, J., Alcolea-González, J. J., Cantelejo-Duarte, P., Collado, H., de Balbín, R., Lorblanchet, M., Ramos-Muñoz, J., Weniger, G.-Ch. & Pike, A. W. G. 2018. U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art. Science 359, 912-915.