Like many of us, I have long enjoyed looking at the Crystal Palace dinosaurs and other prehistoric animal models, created in 1854, still on show more than 160 years later, and providing a remarkable showcase of ancient life as it was imagined at the time. But I’ve only ever seen them from afar. How fantastic would it be to examine them up close? Well…

Caption: you’ve seen the Crystal Palace dinosaurs before (or images of them, anyway), but you might not have seen them up-close like this. Neither had I prior to this very special visit. Image: Darren Naish.

Way back in September 2018, I was fortunate enough to attend the Crystal Palace Dinosaur Days event, part of the Heritage Open Days weekend occurring across the UK on the weekend concerned. I gave a talk and also led a tour around the prehistoric animal models (focusing on the reptiles and amphibians alone). Adrian Lister (of mammoth and Megaloceros fame) led a tour too, Mark Witton gave a talk on ‘Palaeoart After Crystal Palace’, and much else happened besides. I also have to mention the 3D-printed models of the dinosaurs made by Perri Wheeler. How I would love for these to be commercially available: I’m sure they’d be a success. So, it was a great event; well done Ellinor Michel and everyone else involved in the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs group (follow them on Twitter at @cpdinosaurs) for putting it together.

Caption: Perri Wheeler’s brilliant models of the three Crystal Palace dinosaurs (from back to front: Megalosaurus, Hylaeosaurus, Iguanodon). As a pathological collector of model dinosaurs, I sure would like to own a set, but I also sure would like for these models (or a set very similar to them) to be commercially available. Image: Darren Naish.

The real thrill, however, was not the talks nor the presence of the amazing and sometimes spectacularly good speakers but the fact that we were awarded special, up-close access to the prehistoric animal models. A dream come true. As you’ll know if you’ve visited Crystal Palace or read about it, the models are located on islands surrounded by a snaking waterway. In other words, they aren’t readily accessible. For the duration of Dinosaurs Days, however, a temporary bridge had been erected and – like Lord Roxton striding across a felled tree to Maple White Land – we made the crossing and stepped into a bygone era.

Caption: the amazing, enormous head of the Mosasaurus. Many of the scales on the body were recently repaired as the entire skin across the body was in a poor state. More on the mosasaur below. Image: Darren Naish.

Why erect a bridge to the islands in the first place? Both so that crucial landscaping and gardening can occur, and so that the models can be examined and evaluated for repair. They’re not in the best of shape, you see, and much work needs doing. Indeed, right now there’s a major push to get funding for a permanent bridge that will allow the continual access that’s required. This project only has a few days of fundraising left and there’s some way to go before the target is reached: go here and chip in if you can. You might have heard that the Mayor of London agreed to partly fund the project… as has legendary musician and song-writer Slash, since it turns out that he’s a big fan! I should add that Slash seems to be quite the fan of science in general, his twitter account revealing a definite tendency to use his powers for good.

Caption: the standing Iguanodon was given renovation and a new paint scheme within recent years. Unfortunately, further repair work is already required. Image: Darren Naish.

The reason I’m writing this article is not just to bring attention to this push for funding, but also to discuss and illustrate various of the remarkable details I got to see thanks to this up-close encounter. Before I start, be sure to read (if you haven’t already) the August 2016 TetZoo ver 3 article on the Crystal Palace models. Thanks to the Dinosaur Days event, I should add that I’ve been able to get hold of the guide that Richard Owen wrote to accompany the exhibition, or the 2013 reprinting (Owen 2013) of this 1864 publication (Owen 1854), anyway. It provides at least some background information on why the animals look the way they do.

Caption: head of the reclining Iguanodon. Only a privileged few have seen the head from its left side. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: again, relatively few people will have seen the reclining Iguanodon from this side. It’s striking how natural, realistic and well-proportioned the model looks in this view: very much like a real animal. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Hylaeosaurus was thought by Owen and Hawkins to be an iguana-like reptile with a “lofty serrated or jagged crest, extended along the middle of the back”, though many aspects of the reconstruction were noted as being “at present conjectural” (Owen 2013, p. 18). Image: Darren Naish.

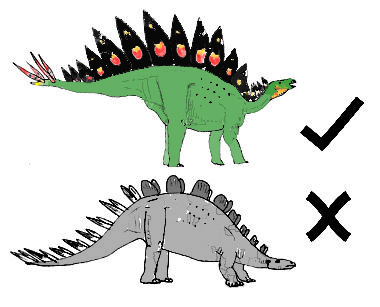

I’ll avoid repeating here the same points I made in my 2016 article but I will repeat my primary take-homes. Namely, that it’s disingenuous and naïve to criticise the models as outdated or as inaccurate, laughable follies, as is sometimes done. They have to be seen within the context of what was known at the time, there has to some acknowledgement of the fact that scientific knowledge has improved over time, and there should also be recognition of the fact that the models are more up-to-date than, and superior in technical accuracy and craftmanship to, the vast majority of modern efforts to portray prehistoric life. In the interests of correcting a mistake made in my 2016 article I should also point out that Crystal Palace is not in Sydenham as I stated, but in Penge. With that out of the way…

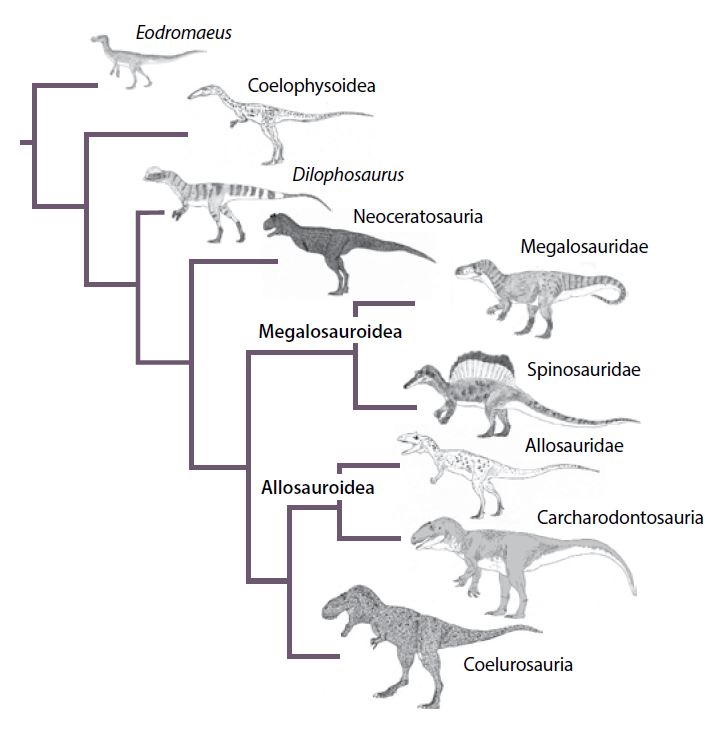

Caption: the pachydermal, vaguely bear-like Megalosaurus is actually a composite of information compiled from both Jurassic and Cretaceous theropods. The tall shoulder hump was included because Owen erroneously regarded the tall-spined Altispinax (previously Becklespinax) vertebrae as belonging to the shoulder region of Megalosaurus (Naish 2010). Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: a lot of detail was added to the megalosaur’s face, some of it is superficially crocodylian-like. Note the ominous cracks at the tip of the nose and along the side of the lower jaw. Image: Darren Naish.

It was a real thrill to see the remarkably detailed appearance of the three Crystal Palace dinosaurs: Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus. Each has a very different skin texture, the Megalosaurus being the most unusual in that it doesn’t have the tile-like scales of the other two. Instead, it’s decorated with a crazy-paving-like covering. It’s not clear what Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (the designer and model-maker) was trying to achieve here since this is a rather non-reptilian look. Perhaps the aim was to give the animal a fissured skin texture vaguely like that of elephants.

Caption: view of the interior of the standing Iguanodon, with and without flash. The light at the far end of the image is coming in through the Iguanodon’s mouth. Image: Darren Naish.

Holes on the undersides of the Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus mean that their insides can be inspected. As you can see from my photos, the models look like weird gabled roofs from the inside, numerous metal struts and poles helping to provide support. The hylaeosaur’s original head was removed since its weight was causing the model’s neck to break, and was replaced with a fibreglass copy. So, peer inside the hylaeosaur from beneath and you see the translucent interior of its face.

Caption: a view of the hylaeosaur’s interior! Image: Darren Naish.

Cracks, fissures and damaged sections are visible everywhere, moss invades and covers parts of the hylaeosaur’s flanks (not good if you want the models to persist) and sections of the megalosaur’s nose look like they could fall off at any moment. Similar damage is present on some of the other models, their skin and scales flaking or cracking or looking to be in imminent danger of breaking or falling off. Some substantial (expensive) repair work has been done by the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, but much more is required.

Caption: looking into the mouth of the Mosasaurus. “The large pointed teeth on the jaws are very conspicuous; but, in addition to these, the gigantic reptile had teeth on a bone of the roof of the mouth (the pterygoid), like some of the modern lizards” (Owen 2013, p. 11). Image: Darren Naish.

In my previous Crystal Palace article, I discussed the fact that the models reveal a great many complex anatomical details, some of them involving details only familiar to specialists. When you see the models up close, even more such details become apparent. I’m not sure I knew that the mosasaur is equipped with accurate palatal teeth, for example. Owen specifically referred to this feature in the guidebook (Owen 2013). The temnospondyls (‘labyrinthodonts’) have big palatal teeth as well, as they should.

Caption: anterior view of one of the temnospondyls. Check out the accurate palatal teeth. To Owen and Hawkins, this animal was Labyrinthodon salamandroides, a sort of composite based on temnospondyl bones and teeth, and inferences made from croc-line archosaur footprints, thought by Owen and those who followed his work to be made by Labyrinthodon. Image: Darren Naish.

Like the dinosaurs (except the megalosaur), the surviving pterosaurs are fantastically scaly (today, we think that pterosaurs were covered in a filamentous coat, except on their wings, the distal parts of their hindlimbs and their snouts and faces). Unfortunately, the pterosaur with folded wings has recently been damaged, its smashed snout and lower jaw meaning that you can see right inside its head. This reveals a complex internal ‘anatomy’: another reminder that the models weren’t all built to the same plan or in the same style, but that very different approaches were used for each.

Caption: the two large Crystal Palace pterosaurs represent the species known to Owen and Hawkins as Pterodactylus cuvieri (though the possibility that more than one species is represented is raised by Owen’s remarks in the accompanying guide). Unfortunately, one of the models is now badly broken. The two smaller pterosaur models are not currently on display and have had a really unfortunate history: they’ve been vandalised, broken and stolen several times. Image: Darren Naish.

Both big pterosaurs stand atop a small rocky ’cliff’. Like all the geological structures in the park, this is an installation specially created as part of the display. It looks, at first sight, to be made of nondescript grey rock. While looking at it, I began wondering about its specific composition, since we know that the other chunks of rocks in the park aren’t just random lumps of local geology, but transplanted sections of the specific geological unit the respective animal’s fossils come from.

Caption: as per usual, the model up-close - this is the Pterodactylus cuvieri posed with open wings - is a remarkable bit of craftmanship. Pterodactylus cuvieri was named for bones that have more recently been included within the genera Ornithocheirus and Anhanguera, and have most recently been awarded the new name Cimoliopterus. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: and here’s a close-up of that detail. I absolutely adore the work here; check out all those individual scales. It seems remarkable now to think that Owen and Hawkins really imagined pterosaurs to look like this, but here’s the evidence. Image: Darren Naish.

What, then, are these pterosaurs really standing on? Mark Witton and I examined some freshly broken fragments of the cliff – the rock is chalk! This really shouldn’t have been a surprise given that the fossils these reconstructions are based on come from the English Chalk (Owen 2013), but it was great to see it confirmed. There’s even a line of dark flint nodules, just as there is in real chalk cliffs. These details are surely known to specialist researchers but were news to me.

Caption: broken sections of the ‘pterosaur cliff’ reveal that we’re looking at chalk… which isn’t a surprise, and is exactly what we would expect, but here’s confirmation. You should be able to see a few of the dark, shiny flint nodules too. Image: Darren Naish.

Look – below – at the photo of the teleosaurs. Notice how the arrangement of scales and scutes is highly detailed, and how the animals have been given a scute arrangement that very much resembles that of living crocodylians. As it happens, the arrangement they’ve been given is dead wrong for teleosaurs but it is absolutely accurate for living crocodylians (where dorsal scute arrangement is – mostly – diagnostic to species level). What I’m saying is that I think that Hawkins looked at living Saltwater crocodiles Crocodylus porosus when designing these amazing models, since their dorsal scute pattern specifically matches this species (and, surprisingly, not gharials).

Caption: the two Teleosaurus of Crystal Palace. While compared by Owen with gharials, it’s interesting that the dorsal scute pattern they were given is very clearly based on living crocodiles. As per usual, look at the remarkable amount of well-rendered detail. Image: Darren Naish.

As usual, there’s stacks more I want to say, but time is up. I had such a great time seeing the models up close and I can’t wait to do it again. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the Crystal Palace prehistoric animals are among the most scientifically and historically important renditions of ancient creatures ever created, and they’re amazing pieces of art, construction and craftmanship to boot. A full, thorough discussion of their ‘anatomy’, backstory, construction and history has, even today, never been published – McCarthy & Gilbert (1994) is the closest thing to it – and much remains to be compiled and discovered.

These models must be preserved for the future. On that note, don’t forget to pledge your support for the bridge project. Crystal Palace and its models will be covered here again at some point in the future, and various relevant projects will be discussed here in 2019 – watch this space!

As should be obvious from these photos, the entire area has become somewhat overgrown recently, and much maintenance is needed. The Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs group are doing what they can, but help is needed. Image: Darren Naish.

For other TetZoo articles on the Crystal Palace prehistoric animals and other relevant issues, see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012

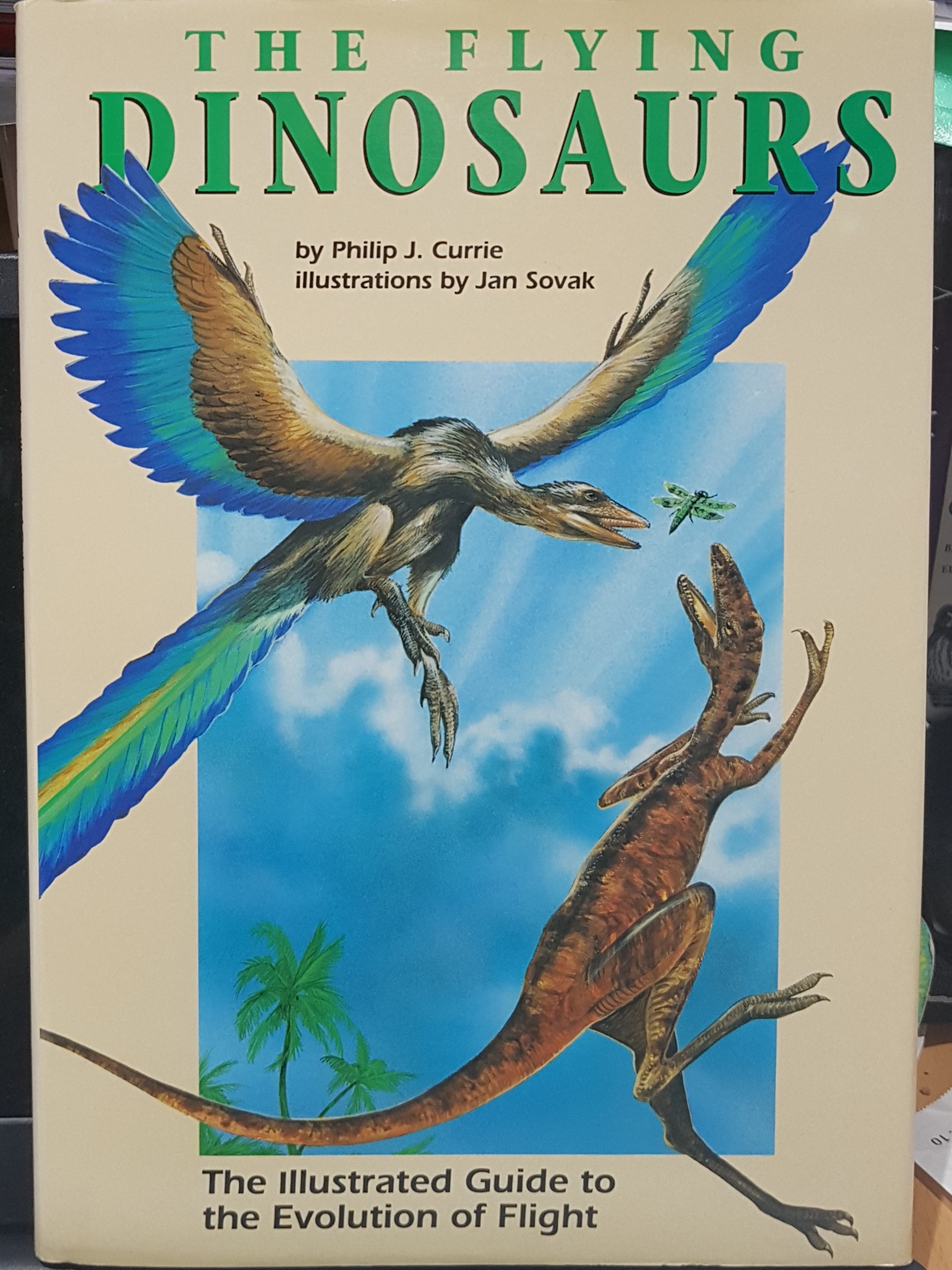

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

Refs - -

McCarthy, S. & Gilbert, M. 1994. Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The Story of the World’s First Prehistoric Sculptures. Crystal Palace Foundation, London.

Naish, D. 2010. Pneumaticity, the early years: Wealden Supergroup dinosaurs and the hypothesis of saurischian pneumaticity. In Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343, pp. 229-236.

Owen, R. 1854. Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Crystal Palace Library and Euston & Evans, London.

Owen, R. 2013. Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Euston Grove Press, London.