The fossil record is a cruel and fickle mistress, and there are a vast many fossil animals for which key data on lifestyle and biology is simply not preserved, or – at least – not known. Yet…

Caption: images that depict tapejarids as herbivores or frugivores are few and far between, but they do exist. Inspired by my reading of Peter Wellnhofer’s 1991 book on pterosaurs, I once chose to depict Tapejara as a leaf eater; the image at right – from issue 95 of the Orbis Dinosaurs! partwork (published 1994) – shows Tapejara as a frugivorous fruitbat/hornbill mashup. Images: Darren Naish; © Robin Bouttell.

How did the toothless azhdarchoid pterosaurs of the Cretaceous make a living? Azhdarchoids include mid-sized, relatively short-jawed groups (‘mid-sized’ = wingspans of 1.5-2m) – I’m thinking of the tapejarids – as well as much longer-jawed, mostly larger (wingspans 4-10m) groups, like the fantastic and rightfully famous azhdarchids. It is mandatory to your understanding of this article that you pay attention to the difference between azhdarchids and azhdarchoids, by the way.

Caption: this reconstructed (model) skeleton of the Brazilian tapejarid Tupandactylus imperator, formerly on show at the Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro (tragically ruined by fire in 2018), shows the deep rostrum, pointed jaw tips and remarkable bony crests (on the snout, rear of the skull, and lower jaw) typical of this azhdarchoid pterosaur group. Image: Darren Naish.

Tapejarids as omnivorous ‘hornbill pterosaurs’. Almost immediately after their 1989 recognition, experts drew attention to an approximate similarity between tapejarids and hornbills. And thus was born the hypothesis that tapejarids might have been frugivorous (Wellnhofer & Kellner 1991). Later authors built on this, and by the time I wrote a book chapter dedicated to this pterosaur group in 2010, the hypothesis of tapejarid frugivory or herbivory was widely considered a reasonable one.

Yes, a book chapter; one that to this day remains unpublished. Back in the 2000s, a team of editors who shall remain nameless made efforts to get a giant, pterosaur-themed textbook off the ground. Several authors – myself among them – submitted manuscripts. But alas, the book was destined never to appear. Months of time and effort were wasted. This happens a lot in academic publishing and it (partly) explains why some of us are so weirdly reticent about committing to new projects, though there are other reasons too, for sure. I’m just lazy, for example. Here, shared publicly for the first time, is an edited version of part of the tapejarid palaeobiology section from my aforementioned and ill-fated, unpublished book chapter…

Caption: once upon a time, this was going to happen. Even the publishers (Cambridge University Press) were taking it seriously enough to put this ad online.

At the time of writing, no detailed or empirical work on tapejarid palaeobiology has been published, with the exception of an abstract by Meijer et al. (2007). Several different ecological roles have been imagined for tapejarids. Wellnhofer and Kellner (1991) regarded it as most likely that tapejarids were frugivores: the short, narrow head might, they speculated, have been well suited for arboreal foraging, and they noted that pointed bill tips appear “a perfect tool for picking or plucking fleshy fruits” (Wellnhofer and Kellner 1991, p. 103). A superficial similarity with the (mostly) frugivorous hornbills was also suggested to support frugivory, as was the relatively small wingspan and body size of Tapejara wellnhoferi. Wellnhofer and Kellner (1991) noted that Fleming and Lips (1991) had hypothesized the existence of frugivory in pterosaurs given the apparent ecological requirement for dispersers of angiosperm fruits and seeds during the Cretaceous. The hypothesis of frugivory for tapejarids was also mentioned by Unwin (2006, p. 99).

Caption: tapejarid skulls aren’t quite like those of any living animal group, but they resemble those of hornbills more than those of anything else. In the two skulls here (Tupandactylus navigans at left, Tu. imperator at right), the orbit (eye socket) is the small, subcircular opening at the rear, way outsized by the massive antorbital fenestra. Both of these specimens show how the bony crests were continuous with giant, sheet-like soft tissue extensions. Images: Mark Witton; Darren Naish.

Morphometric and comparative work on tapejarid crania lend support to Wellnhofer and Kellner’s (1991) hypothesis that these pterosaurs were terrestrial omnivores or herbivores. Meijer et al. (2007) used multivariate morphometric techniques to analyse jaw structure in Tapejara wellnhoferi and concluded that it could not generate enough force to crack seeds or other hard objects; however, other kinds of herbivory could not be excluded. As described above [in a descriptive section not included here], the retroarticular process on the tapejarid mandible is unusual in being proportionally large, and in having a sloping dorsal surface. Among birds, a similarly shaped retroarticular process is present in some hornbills. Contrary to expectations, this does not support an unusual large depressor mandibulae compared to that of related birds (hoopoes and wood-hoopoes); instead, the ventral part of the pterygoideus ventralis lateralis, associated with the posteroventral part of the jaw, is particularly bulky in hornbills (Burton 1984). This is combined with a gently decurved, laterally compressed rostrum and a heavily ossified palate (the so-called ‘doubly desmognathous’ condition of Beddard (1898)) where the palatines and other elements form a robust, unfenestrated sheet anterior to the orbits. While the sequence of transformations leading to the evolution of the tapejarid palate within Pterosauria were altogether different from those that culminated in the doubly desmognathous palate of hornbills, the unfenestrated palatal sheet present in Tapejara wellnhoferi (and probably other tapejarids as well) is superficially much like a hornbill palate.

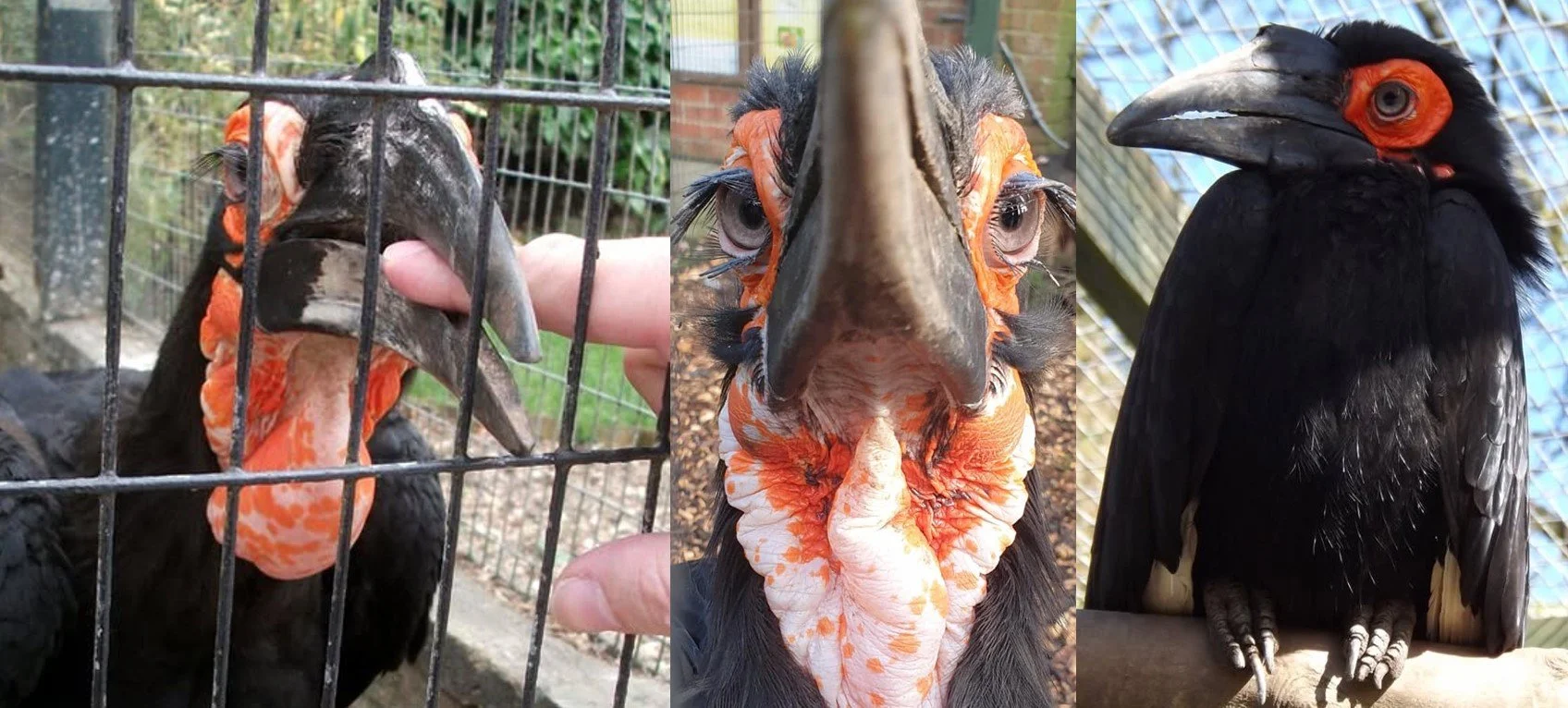

Caption: I’ve been bitten by several hornbill species in my time, albeit never with malicious intent. This is a captive Trumpeter hornbill Bycanistes bucinator photographed in 2012, a mid-sized African species. Hornbills like this differ from tapejarids in having a curved bill, but this isn’t the case in all of them; the two groups are similar in skull proportions and in being highly pneumatic in the rostrum. Image: Darren Naish.

In conclusion, tapejarid skull and lower jaw shape, and inferred wing loadings and wing shape, suggest an ecology and lifestyle most similar to that of scansorial, omnivorous birds such as hornbills, as proposed by Wellnhofer and Kellner (1991).

* A different generic name was used in the book chapter, but we don’t need to worry about that.

So, there we have it: Naish (unpublished) supported frugivory – or, at least, omnivory involving frugivory – in tapejarids. And here’s where this becomes newsworthy, because an interesting publication just out in the pterosaur literature reports the discovery of phytoliths (microscopic mineral grains that some plants embed within their tissues) and gastroliths (swallowed stones used to aid digestion) within the gut of the Chinese tapejarid Sinopterus (Jiang et al. 2025). This is (so far as I can tell from what’s been released so far) good evidence for herbivory of some sort in Sinopterus. Wow – hypothesis confirmed!

Caption: montage from Jiang et al. (2025) showing preserved stomach contents of the tapejarid Sinopterus, revealing gastroliths and phytoliths, and thus evidence for herbivory of some sort. I can’t say much more at this stage since the paper has only been released as a preprint that I can’t access. Image: Jiang et al. (2025).

Azhdarchids as ‘giraffized’ herbivores. Inspired by this discovery, the very excellent artist and purveyor of… interesting ideas Hodari Nundu recently posed the following interesting question on social media: “what evidence do we have to confidently say azhdarchids were predators and not a sort of giraffized version of vegetarian tapejarids?”. Oh ho ho, a challenge! I will note to start with that the whimsical linking of azhdarchids with giraffes has happened before, and I must avoid elaborating on it here.

Caption: it’s a most curious and interesting thing that azhdarchids (and similar azhdarchoids) acquired superficially artiodactyl-like proportions, albeit with wings and a very different skull. And thus, we find justification for the flightless, superficially giraffe-like pterosaurs of Spec Zoo, right? Follow the links below if you’re interested. Images: © Steve Holden/Dougal Dixon; Darren Naish.

That aside, here are my thoughts on this matter. Imagine we live in a world where any and all direct data on azhdarchoid diet is absent… as we did until a few weeks ago (Jiang et al. 2025). At that time, the only thing we had to go on when it comes to azhdarchoid ecology and diet is form-function correlation: the idea that we can use the shape of an animal and its body parts to infer its natural history, mostly via analogy with living animals.

Caption: views have differed on whether hornbills were ancestrally mostly frugivorous and then gave rise to the mostly predatory ground hornbills, or whether mostly predatory ancestors gave rise to the mostly-frugivores. Either way, the differences between the two sorts aren’t that profound: they’re certainly less different than azhdarchids are from tapejarids. Here are captive Southern ground hornbills Bucorvus leadbeateri. Images: Darren Naish.

As discussed above, tapejarids are sufficiently similar in jaw and skull shape for us to hypothesize that they might have been omnivorous and partly or mostly frugivorous, and perhaps similar in feeding habits to birds like hornbills. Azhdarchids are different from tapejarids in having radically long, narrow, spear-like jaws. If we’re playing that ‘form-function correlation’ game, azhdarchids most recall storks and ground hornbills (Witton & Naish 2008). Ergo, we should – in the absence of evidence to the contrary – hypothesize that they were similar to storks and/or ground hornbills in feeding habits and diet.

Caption: there will come a time when I’ll stop talking about the impact of, and publicity associated with, the Witton & Naish 2008 ‘terrestrial stalking’ paper, but that time is not today. Here are screengrabs showing a few of the treatments the story was given by the great British press. Cor blimey, wot a whopper, Gary Lineker’s woke pet donkey stole my garden shed, and so on.

Readers aware of the literature on azhdarchids will know that this is exactly what we have been hypothesizing at least since Mark Witton and I published our initial ‘terrestrial stalking’ paper back in the 2000s (Witton & Naish 2008). While we mostly view these animals as predatory – as faunivorous or animalivorous (yes, these terms really are in use and preferable to ‘carnivorous’ when it comes to a diet involving small animals) – we’ve noted that a generalist, omnivorous diet is conceivable. Here’s what Mark and I said in a 2015 study…

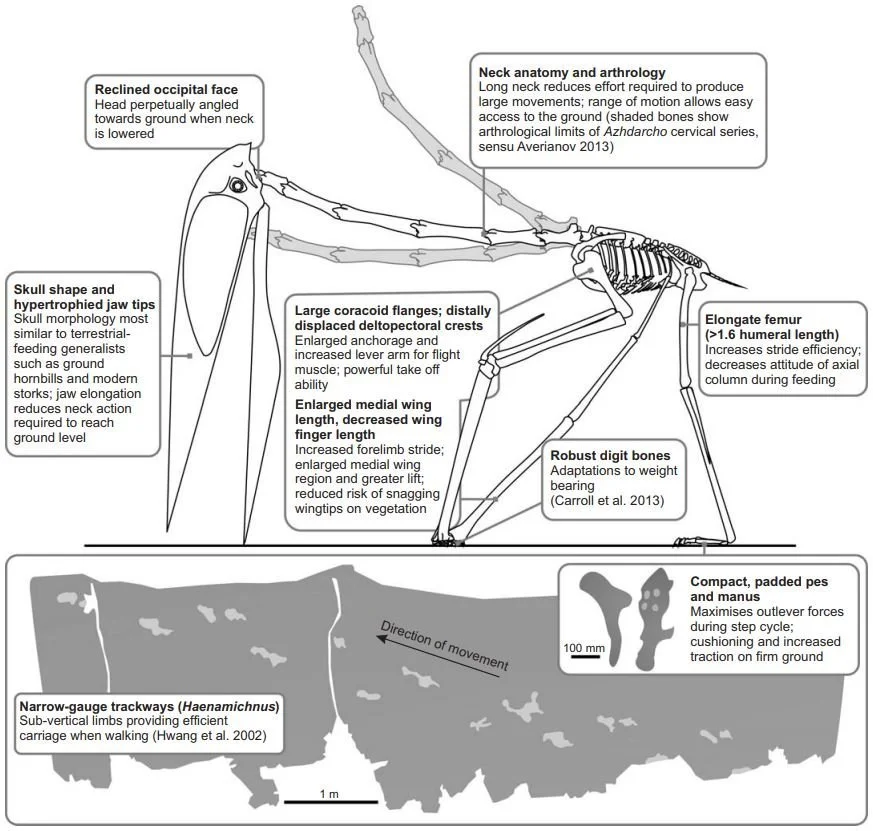

We interpreted the elongate necks, hypertrophied, stork-like rostra, and distinctive limbs of azhdarchids as adaptations to “terrestrial stalking”, a lifestyle akin to that of modern ground hornbills and large stork species in which small foodstuffs (e.g., fruit, carrion, invertebrates, and small vertebrates) are procured during sustained periods of terrestrial foraging. (Witton & Naish 2015, pp. 651-652)

Caption: numerous aspects of azhdarchid anatomy provide support for the view that these animals were terrestrial stalkers that picked up animal prey from the ground; the hypothesis is different from most of those proposed for pterosaurs in that it isn’t based on just one perceived trait or adaptation. Image: Witton & Naish (2015).

Note the mention of fruit. Yes, it’s conceivable that a hungry azhdarchid encountering a tree laden with fruit could consume some quantity of it, just as some mostly predatory animals will do today. But, otherwise: we think that mostly predatory is the lifestyle we should be imagining. Here are some additional points that might show why this view is preferable to a more herbivorous one…

The long, pointed azhdarchid rostrum does not appear suiting to the snipping, breaking or processing of plant parts. More study is needed, but a specialized herbivorous lifestyle would surely involve the evolution of shorter jaws with a shorter level arm, as is the case in tapejarids.

Azhdarchids appear to have been habitat generalists, with taxa known from deserts and semideserts as well as regions dominated by arid savannah, parkland, open woodland and subtropical riparian forest, and there are taxa of coastal habitats too. Given that they were likely good at covering distance (I’m not convinced by the argument that they were burst-fliers and more like bustards than storks), it might be that their presence in any one habitat does not necessarily require that they had to make a living there. However, the impression I get from their distribution is more consistent with that of generalist predators, able to exploit animal prey of diverse sort. They aren’t consistently associated with places where we have good evidence for ecologically ‘reliable’ vegetation.

Caption: variation in neck proportions and skull shape in particular show that not all azhdarchids were alike, a point made by numerous authors at this point. The remarkably long and slender neck of Arambourgiania, shown here, suggests a lifestyle, ecology and diet quite different from that of azhdarchids with a shorter, more robust neck and skull, for example. Image: © Mark Witton.

Specialized herbivores have relatively large guts and other adaptations for the processing and fermenting of plant material. Azhdarchids have relatively small bodies for their size and all indications are that their carrying capacity for food was low, which is more in keeping with carnivory than a diet regularly involving plants. I and others are working on a project directly relevant to this issue right now.

My main conclusion on azhdarchids is that they were indeed predominantly predatory, and sufficient generalized that they could take advantage of all kinds of small animals, from arthropods and fish to small dinosaurs, other pterosaurs and other reptiles (Witton & Naish 2008, 2015, Naish & Witton 2017). As noted earlier, the idea is already out there (Witton & Naish 2015) that they may well have exploited carrion and some plant foods in the same way that their extant analogues do. We should also always keep in mind that this is a large enough group for there to be all kinds of species-level peculiarities that may well counter the trend otherwise typical for the group. But that, I argue, is where we’re at right now. Study relevant to the issues covered here is underway, and – as ever – we await more exciting news on pterosaur biology and lifestyle.

For previous TetZoo articles on azhdarchids and other pterosaurs, see…

Tiny pterosaurs and pac-man frogs from hell, March 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Daisy’s Isle of Wight Dragon and why China has what Europe does not, March 2013

In Rio for the 2013 International Symposium on Pterosaurs, May 2013

Quetzalcoatlus: the evil, pin-headed, toothy nightmare monster that wants to eat your soul, August 2013

Were azhdarchid pterosaurs really terrestrial stalkers? The evidence says yes, yes they (probably) were, December 2013

Some Azhdarchid Pterosaurs Were Robust-Necked Top-Tier Predators, February 2017

Postcranial Palaeoneurology and the Lifestyles of Pterosaurs, August 2018

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology, the TetZoo Review, September 2020

Baby Pterosaurs Were Excellent Fliers and Occupied Different Niches From Their Parents, July 2021

The Quetz Monograph Lives and Other News on Azhdarchid Pterosaurs, December 2021

Azhdarchid Progress, a Personal View, October 2024

Refs - -

Beddard, F. E. 1898. The Structure and Classification of Birds. Longmans, Green, London.

Burton, P. J. K. 1984. Anatomy and evolution of the feeding apparatus in the avian orders Coraciiformes and Piciformes. Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History (Zoology) 47, 331-443.

Fleming, T. H. & Lipps, K. R. 1991. Angiosperm endozoochory: were pterosaurs Cretaceous seed dispersers? The American Naturalist 138, 1058-1065.

Jiang, S., Zhang, X., Wu, Y., Zheng, M., Kellner, A. W. A. & Wang, X. 2025. First occurrence of phytoliths in pterosaurs—evidence for herbivory. Science Bulletin doi:10.1016/j.scib.2025.06.040

Meijer, H. J. M., Van der Meij, M. M. E., van Waveren, I. & Veldmeijer, A. J. 2007. Linking skull morphology to feeding in Tapejaridae: adaptations to frugivory in Tapejara wellnhoferi. In Hone, D. (ed.) Flugsaurier: the Wellnhofer Pterosaur Meeting. Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology, unpaginated.

Unwin, D. M. 2006. The Pterosaurs From Deep Time. Pi Press, New York.

Wellnhofer, P. & Kellner, A. W. A. 1991. The skull of Tapejara wellnhoferi Kellner (Reptilia, Pterosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of the Araripe Basin, northeastern Brazil. Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Historische Geologie 31, 89-106.