One of the reasons you read TetZoo is because of the dinosaurs, and among the dinosaur-themed things I write about on fairly regular basis are new(ish) dinosaur-themed books.

Partly because I’m way overdue on the book reviews I planned to write during 2019, I’m here going to talk about some recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books that you’d do well to buy and read, if you wish, or can. I’ve written about recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books on quite a few recent occasions; see the links below for more. Let’s get to it.

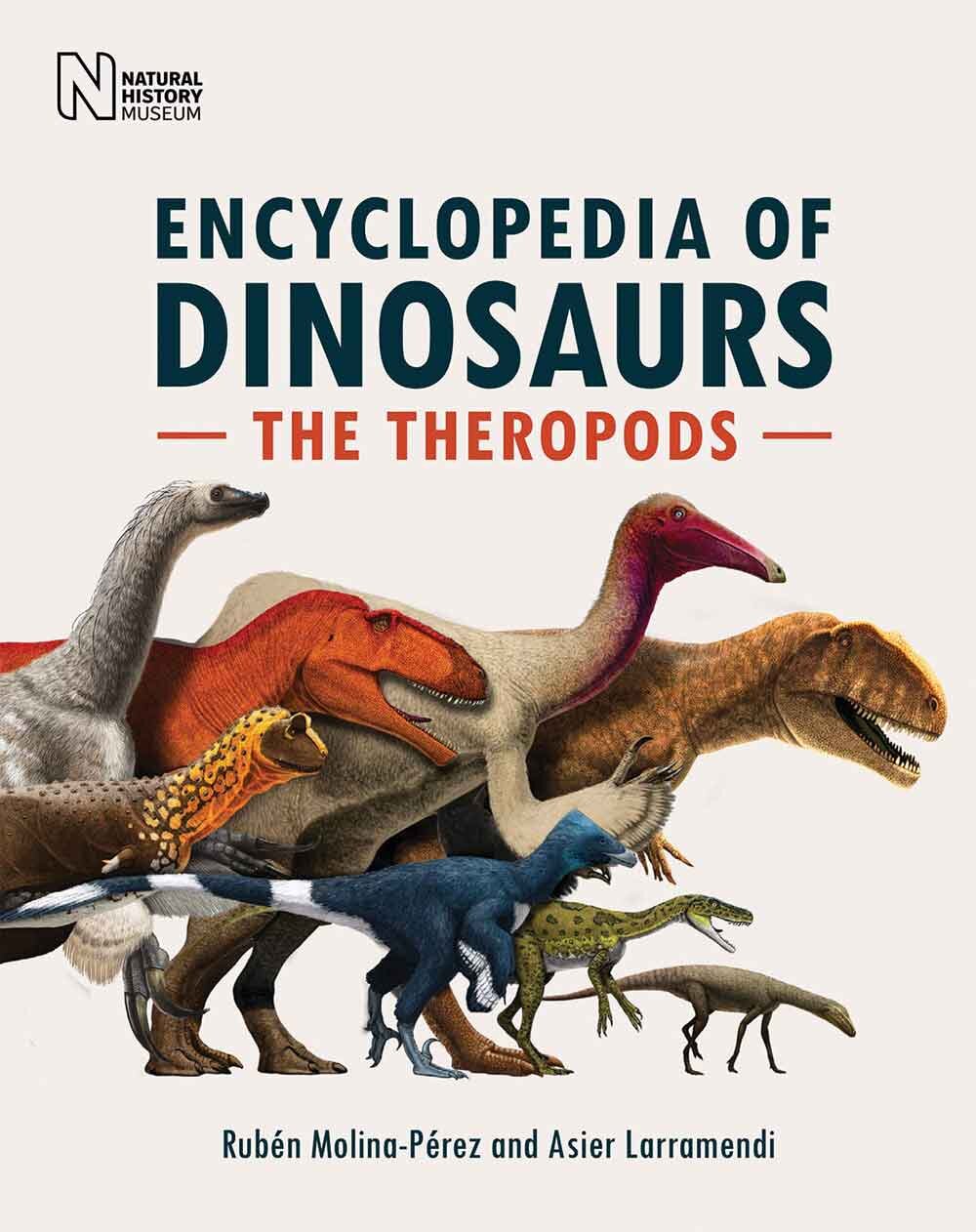

Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: the Theropods, by Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi

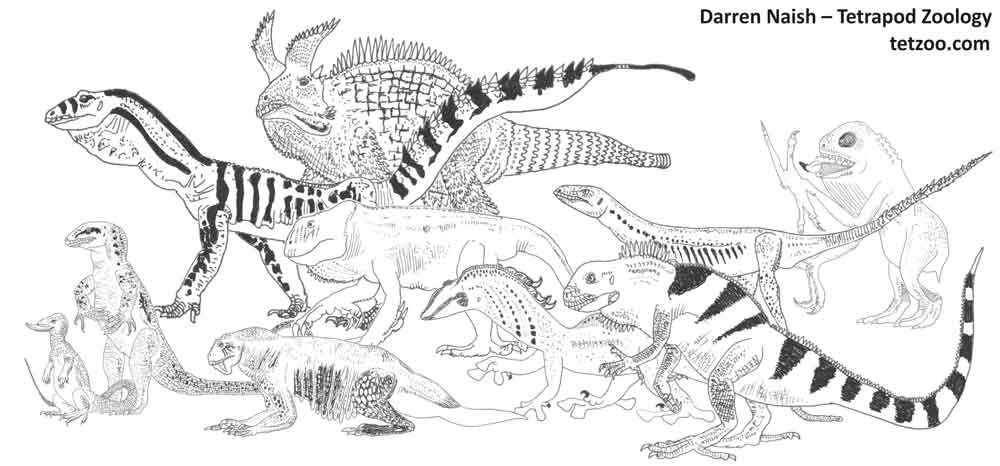

I can say right out of the gate that this 2019 work is one of the most spectacular dinosaur-themed works that has ever seen print. Think about that for a minute, since it’s a pretty grand claim. Yes. This book is spectacular: big (288 pages, and 24.5 cm x 30 cm), of extremely high standard, packed with information, and containing a vast number of excellent and highly accurate colour life reconstructions. Originally published in Spanish, it has now been translated (by David Connolly and Gonzalo Ángel Ramírez Cruz) and published in English by London’s Natural History Museum. The book consists of eight sections, which variously go through the theropod cladogram, discuss geographical regions and the theropods associated with them, and review theropod anatomy, eggs, footprints and so on. And it’s packed with excellent illustrations… hundreds of them.

A selection of pages from Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019). At left, eggs depicted to scale (with a basketball). At right, just two of the many pages that feature theropod skeletal elements. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

The art is great – the majority of colour images being by the phenomenally good and reliable Andrey Atuchin – and I’d recommend that anyone interested in the life appearance of dinosaurs obtain the book for its art alone. I have one criticism of the art though, which is that the colour schemes and patterns used for some of the animals are occasionally based on those of living animals (most typically birds).

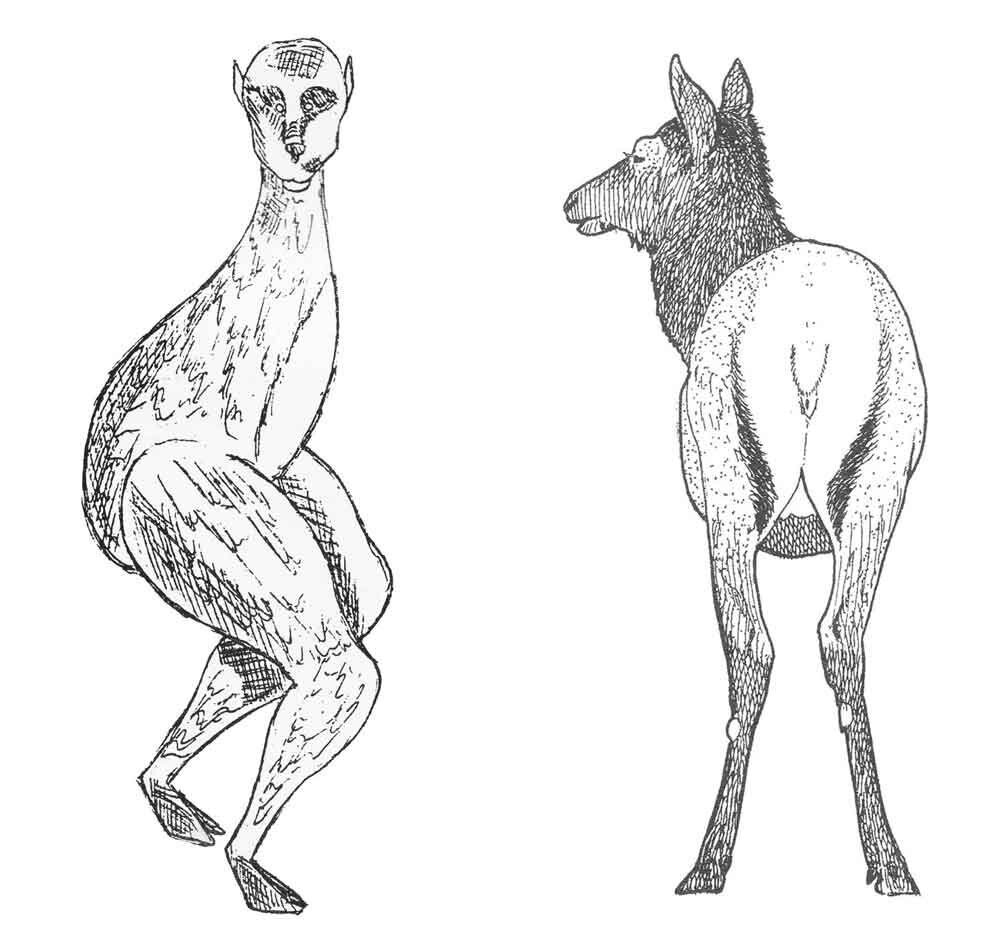

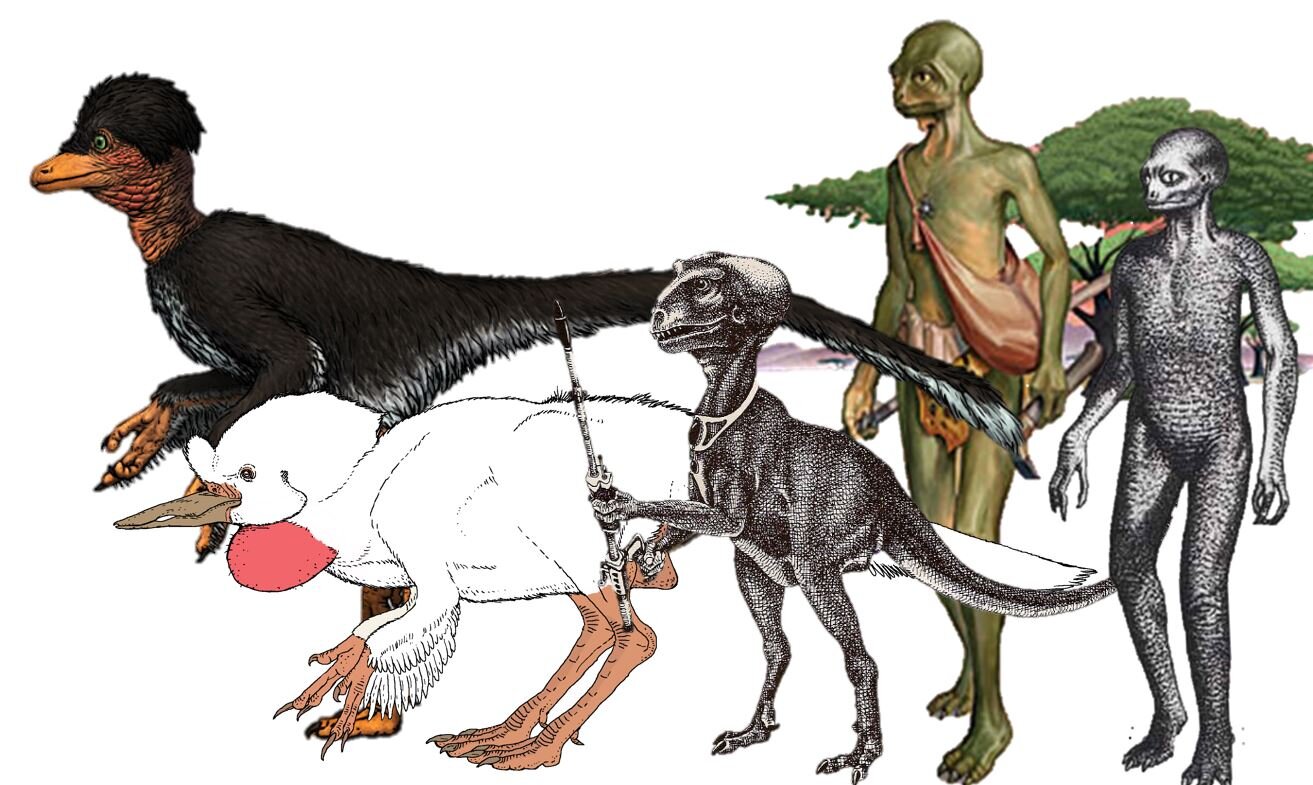

Just two of the many UNNAMED theropod species reconstructed in the book. Exciting stuff! The humans that feature in the book are an interesting lot. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

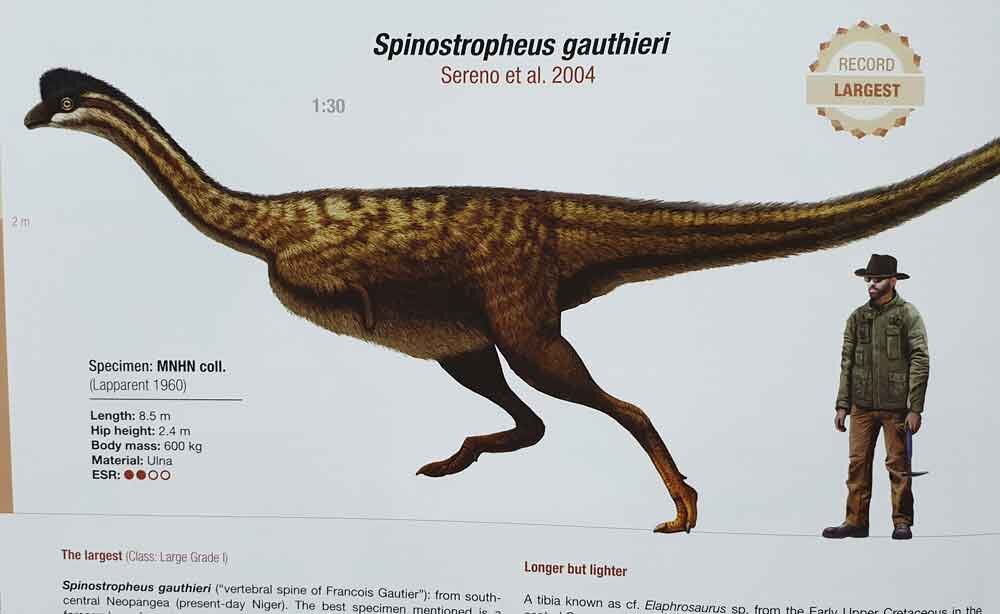

Familiar theropods of many sorts are illustrated, but a major plus point is that many of the animals depicted are either obscure and mostly new to the world of palaeoartistic depictions (examples: Spinostropheus, Dryptosauroides, Bonapartenykus, Nanantius, Gargantuavis) or are as-yet-unnamed species: animals which clearly represent something new (since they’re the only member of their group known from the relevant geographical region and segment of geological time) but have only been referred to by their specimen numbers or by a ‘cf’ attribution (a theropod called, for example ‘cf Velociraptor mongoliensis’ is being compared by its describers to V. mongoliensis and is clearly very much like V. mongoliensis, but quite possibly not part of the species and perhaps something new. The ‘cf’ is short for ‘confere’, as in: compare with).

If the reconstructions in the book are anything to go by, Spinostropheus - according to one specimen (an ulna) it could reach huge sizes - was among the most remarkable of theropods. Just look at it. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

Two issues strike me as problematic though. One is that the arrangement is really difficult to get to grips with, and it’s taken me numerous attempts to understand and appreciate why the book is arranged the way it is. The second issue concerns what appears to be a suspiciously high degree of taxonomic precision for footprints. The authors depict footprints, said to be representative of the different theropod groups covered in the taxonomy section at the start of the book, and seem confident that the tracks concerned (which are often fairly nondescript) were made by species belonging to the relevant group. It’s hard to be convinced that this is reliable, except in a very few cases: I’m happy to agree that the giant Tyrannosauripus pillmorei track, for example, really was made by a member of Tyrannosauridae. Then again, maybe the authors have devised a new track identification method that isn’t yet known to the rest of us.

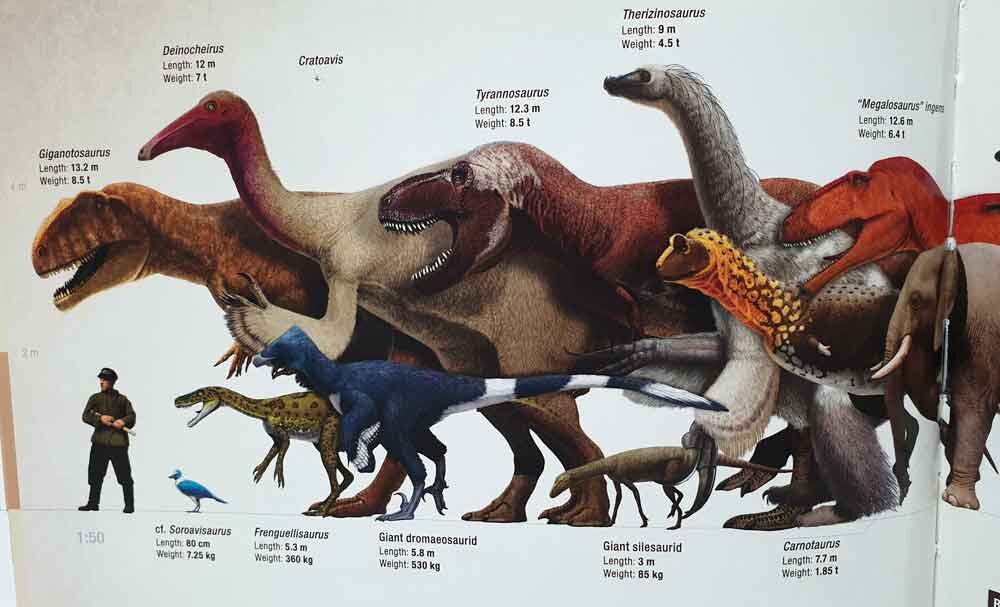

The several montages in the book are truly things of beauty. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

And on that note, it’s obvious that a vast quantity of novel science was performed as part of the background research for this book. The methods and data used by the authors are explained up front. Impressive stuff, and stuff which should be published in the technical literature at some point. Are their results always ‘good’? Well, I have my misgivings about the idea that Dinornis the moa was the fastest (non-flying) theropod ever and capable of sprinting at a phenomenal 81 km/h…

So, so many diagrams of tracks and trackways. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

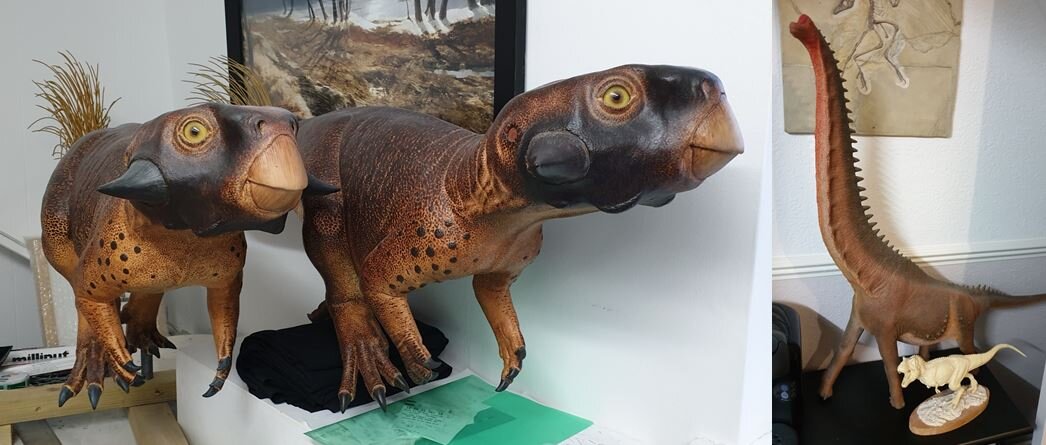

Despite my minor misgivings, this book is attractive enough and interesting enough that it’s a must-have for those seriously interested in dinosaurs and in artistic depictions of them. Buy it if you can. This volume promises to be the first in a series. At the time of writing, the second of these – devoted to sauropods – is being advertised and is due to appear soon. Given that there’s every reason to assume that its artwork and overall quality will be similar to that of the theropod volume reviewed here, I have very high hopes and look forward to seeing it.

Molina-Pérez, R. & Larramendi, A. 2019. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: the Theropods. The Natural History Museum, London. pp. 288. ISBN 9780565094973. Hardback. Here at publishers. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

Luis Rey’s Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects

Luis Rey (who blogs here) has been active in the palaeoart world for a few decades now, and most people interested in the portrayal of dinosaurs in art will be familiar with his vibrant, bold and dynamic style. Luis’s work has appeared in museum installations, exhibitions, and in numerous publications, including books. Most notable among these are his own Extreme Dinosaurs (Rey 2001) and The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, by Robert Bakker (Bakker 2013). I feel it would be wrong at this point to avoid mentioning the fact that Luis and I were regular correspondents back when the first of those books appeared, but that my dislike of the 2013 book – which I made clear in a TetZoo review – coincided with a cessation in any contact we used to have. But things have moved on; Luis’s art has continued to evolve and let’s put all of that behind us.

A collection of Rey works at TetZoo Towers. Image: Darren Naish.

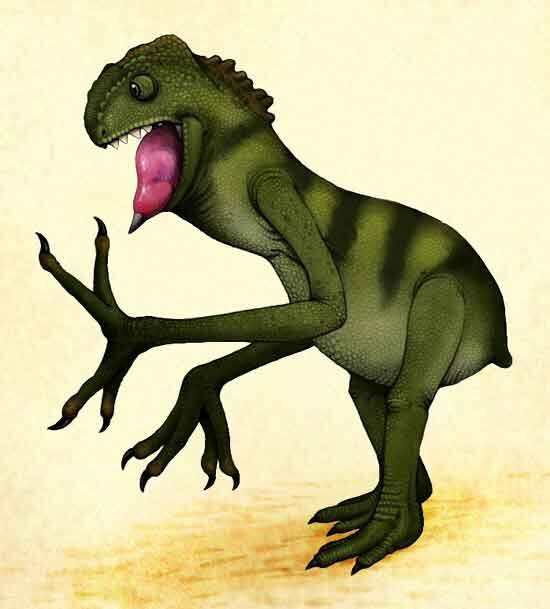

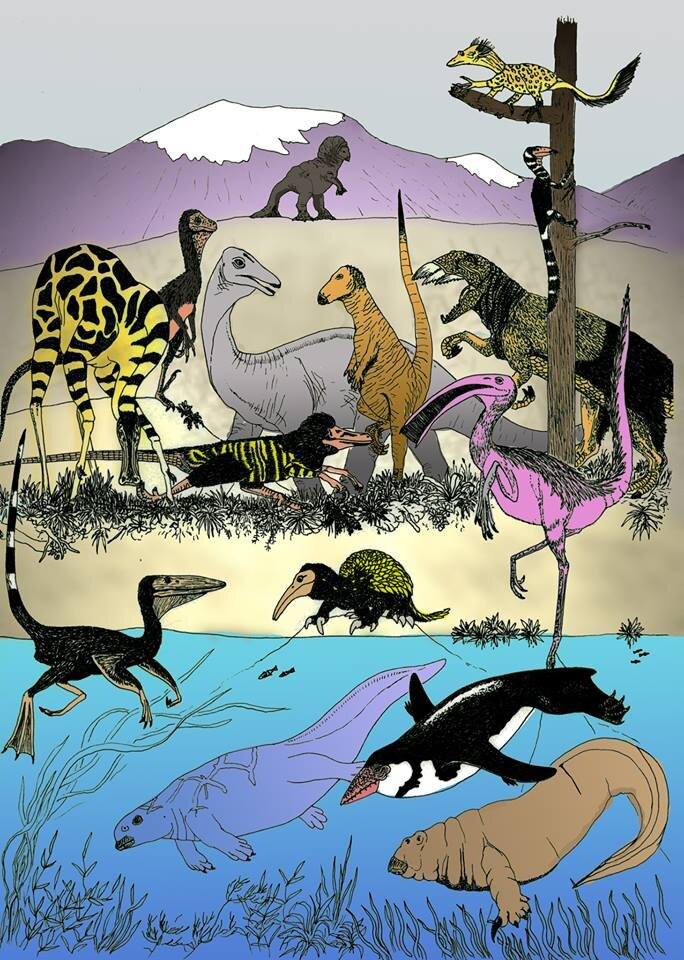

Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects discusses the intellectual and artistic background to several dinosaur-themed museum installations which Luis has created, but does so in an evolutionary fashion such that they’re used to describe our improving knowledge of the Mesozoic world. Luis was illustrating colourful, fully feathered dromaeosaurs, oviraptorosaurs and so on at a time when the majority of relevant academics were dead against this, so it would be fair to see him as one of several artists who were predicting things that would prove correct in the end. I was on side too, and consequently was a vociferous Rey advocate in the early part of my academic career, deliberately using his reconstructions of dromaeosaurs – even the turkey-wattled, shaggily feathered ones – in conference presentations and publications. And for all the success of All Yesterdays and its associated movement, we have never forgotten that Luis was saying many of the same things already.

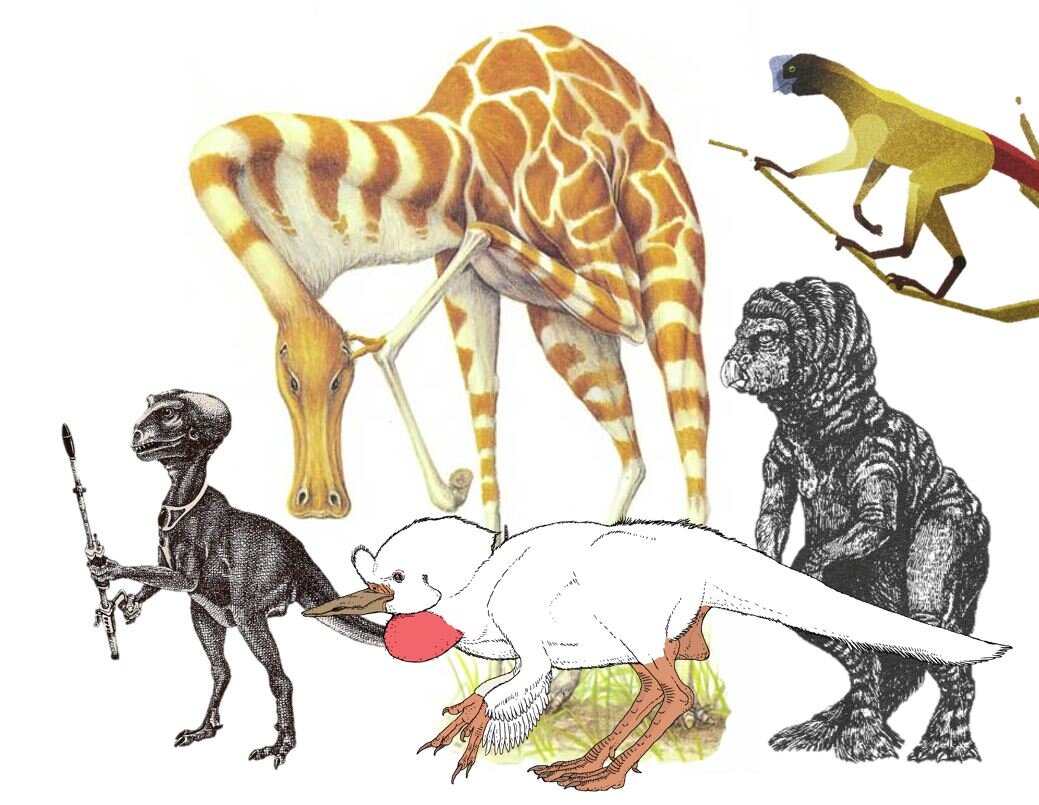

Some representative pages from Extreme Dinosaurs 2. At right, note the person wearing an oviraptorosaur costume while sat in a nest.

Maniraptorans, thyreophorans, ceratopsians, dinosaur eggs and nesting and the dinosaurs (and other Mesozoic reptiles) of Mexico all get coverage here as Luis explains the thinking behind new pieces of art and also how and why he’s modified older ones. Our understanding of feather arrangements in non-bird maniraptorans have improved a lot in recent years, plus we have so much new data on ankylosaur armour, ceratopsian skin and so on. If you haven’t been keeping up, this book would be a good primer. The text is concise and written in a friendly, informal style.

More representative pages, this time depicting therizinosaurs. Brightly coloured faces, bold patterns on the feathering, inflatable throat structures… what’s not to love? Image: Rey (2019).

I’m still not keen on the photo-bashing that’s now integral to the Rey style and don’t find it effective or successful. A few pieces included in the book don’t, therefore, work for me (examples: Santonian hadrosaur hassled by theropods on pp. 104-5, the Labocania scene on pp. 106-7). But can I please emphasise that I still find this a valuable book, and I very much recommend it as an interesting addition to the palaeoart stable, the autobiographical angle in particular being useful. My copy of Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects is an advance softback version but I understand that a hardback is available too.

Rey, L. 2019. Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects. Imagine Publishing, London/Metepec. pp. 139. ISBN 978-0-9933866-2-6. Softback/Hardback. Here at amazon.co.uk.

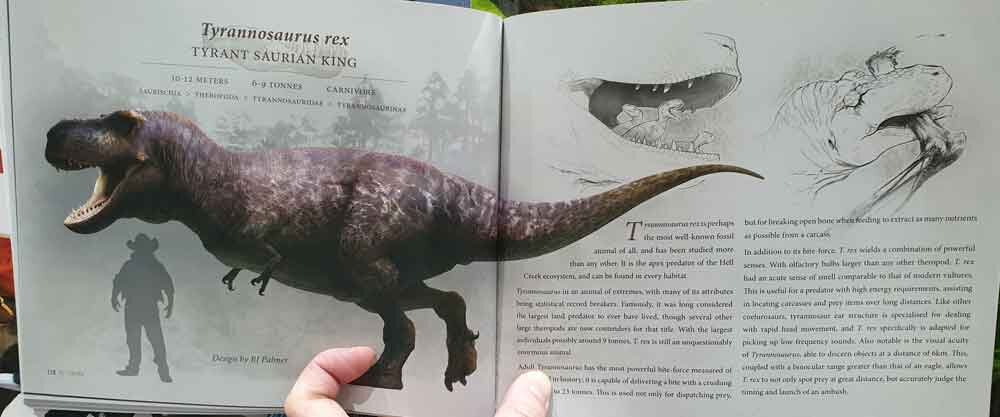

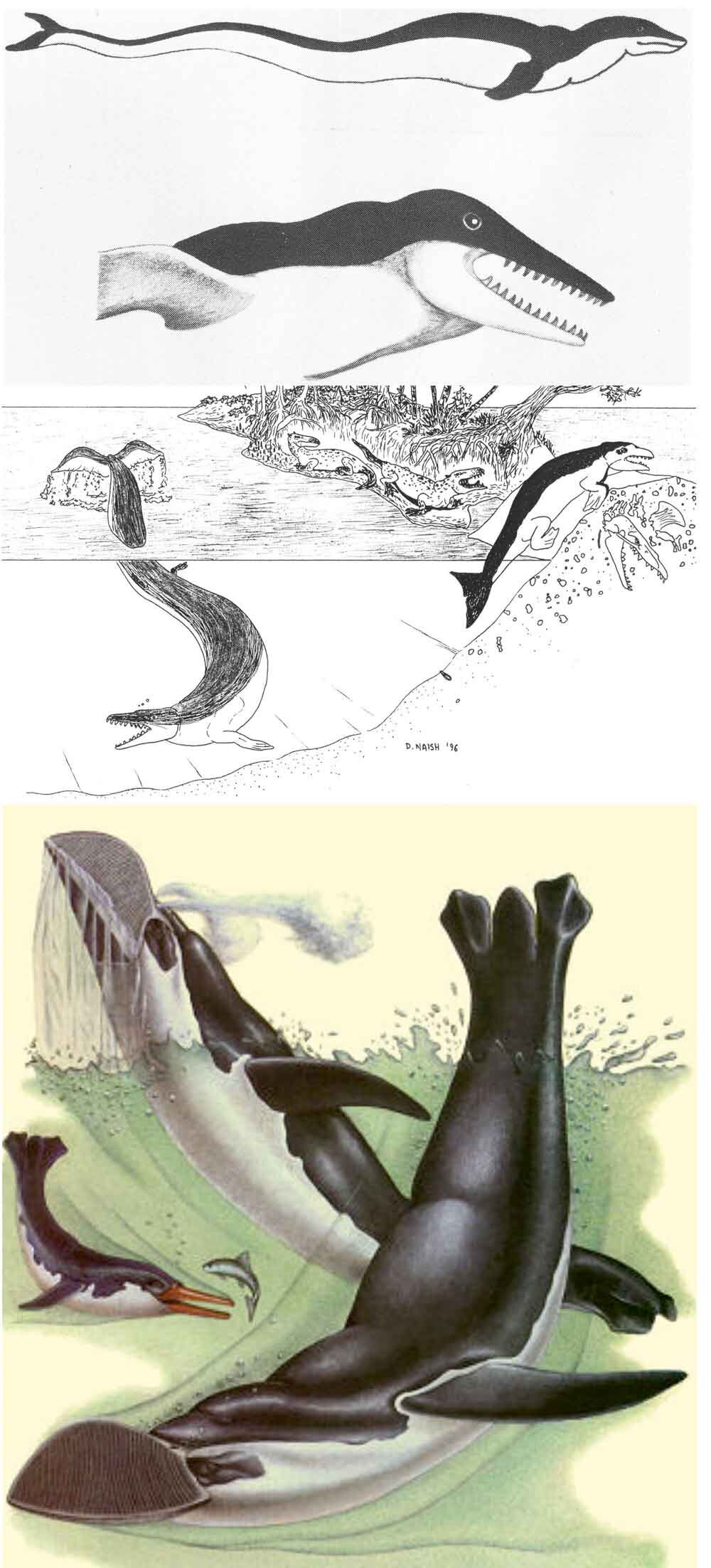

Parker et al.’s Saurian: A Field Guide to Hell Creek

Even if – like me – you’re not a video game buff and have little interest in video games or the playing of them, chances are high that you’ve heard about Saurian, a role-playing, survival simulation experience in which you play the role of a dinosaur negotiating a Maastrichtian environment modelled on that of the Hell Creek Formation. You have to avoid predators, find and procure food, raise babies, and live as long as possible. I’ve played The Simms, back in the day, and recall the urge to sink hours of time into living a virtual tiny life, so I can understand the appeal.

Representative pages, here showing the raptor prey restraint model in action. Poor pachycephalosaur. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

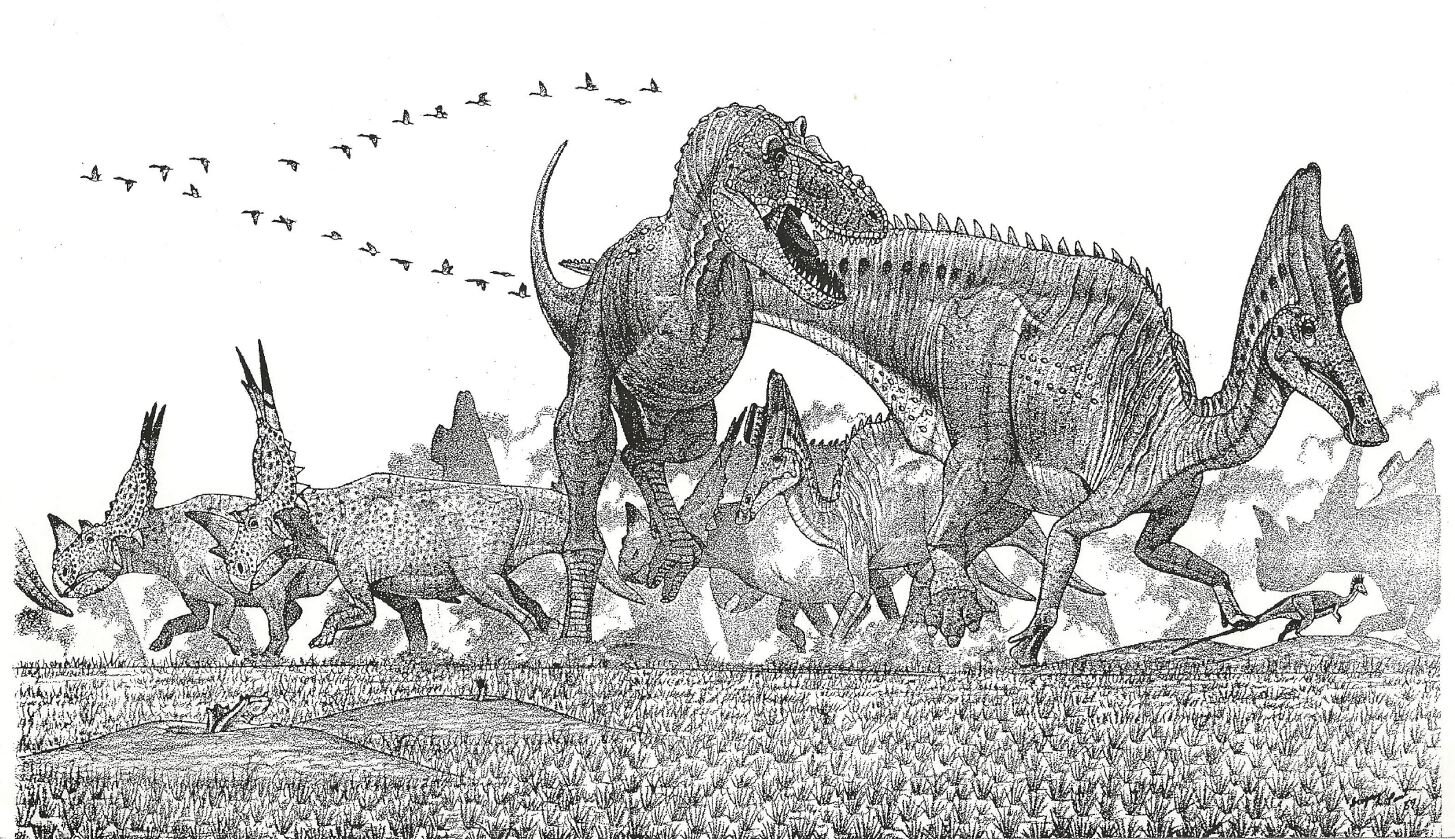

The relevance of Saurian to the TetZooniverse is that the game has been designed and built according to an incredibly high scientific standard, the team behind it having done a vast quantity of research on everything relevant to the Hell Creek world. And the good news is that this work hasn’t been wasted. This book – written by Tom Parker, featuring the artwork of Chris Masna and RJ Palmer (of Detective Pikachu fame and much else), and produced following consultation with a long list of relevant palaeontologists – is the result: it includes a vast quantity of amazing concept art, detailed vignettes and scaled artwork of the organisms and environments that feature in the game, and is simply a joy to look at. The text is brief but functions well. The book is a sturdy softback (20 x 24 cm) of 182 pages, printed to excellent, glossy standard.

RJ Palmer’s T. rex is one of the stars of the show. Some of you will know that the Saurian team abandoned an earlier, more feathery version. Assorted humans function as scale bars; you can likely guess who this one is based on. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

As should be clear by now, the thoroughness of the project’s world-building means that there’s more information here on Maastrichtian North American trees, rainfall patterns, swamps, beaches, amphibians, lizards, crocodyliforms, fishes and so on than you’ve ever seen before. The result is one of the most interesting, detailed and attractive volumes dedicated to Late Cretaceous life. This book is a must-have for those seriously interested in palaeoart and in seeing prehistoric animals and environments depicted in detail, but it’s also good enough that those with a scientific or technical interest in Late Cretaceous life should obtain it too.

Oh wow, so much of the art in this book is just phenomenal. This scene depicts competition among scavengers at a carcass. You might just be able to see the anguimorph lizard inside the body cavity. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

Parker, T., Masna, C. & Palmer, R. J. 2019. Saurian: A Field Guide to Hell Creek. Urvogel Games. pp. 182. Softback. Here at publishers [BUT CURRENTLY OUT OF STOCK].

That’s where we’ll end for now. A few more dinosaur-themed book review are due to appear here soon, including of Donald Prothero’s The History of Dinosaurs in 25 Fossils and Michael Benton’s The Dinosaurs Discovered: How a Scientific Revolution is Rewriting Their Story.

For previous TetZoo dinosaur-themed book reviews, see… (linking here to wayback machine versions due to paywalling and vandalism of TetZoo ver 2 and 3 articles)…

Long and Schouten's Feathered Dinosaurs, a review, January 2008

Luis Chiappe's Glorified Dinosaurs: The Origin and Early Evolution of Birds, January 2011

What they’re saying about The Great Dinosaur Discoveries, November 2011

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, August 2012

New Dinosaur Books, Part 1: Barrett on Stegosaurs, August 2018

New Dinosaur Books, Part 2: Ben Garrod’s ‘So You Think You Know About… Dinosaurs’ Series, August 2018

The Second Edition of Naish and Barrett’s Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2011

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 2013. The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs. Random House, New York.

Rey, L. 2001. Extreme Dinosaurs. Chronicle Books, San Francisco.